|

Three weeks after uncomplicated cataract extraction, a 67-year-old male mentioned that his right eye—the one that had been operated on—wasn’t as clear as he had hoped. He was also undergoing treatment with a topical prostaglandin analog for primary open-angle glaucoma, which he stopped prior to surgery and recently restarted. His best-corrected acuity was 20/50 OD and 20/25 OS. Fundus examination showed a mild macular disturbance, and SD-OCT revealed pronounced cystoid macular edema (CME) as the cause of his visual reduction.

Inflammation

Various factors and mechanisms are involved in CME pathogenesis, including the release of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins.1-4 These mediators disrupt the blood–aqueous barrier (and blood–retinal barrier), leading to increased vascular permeability.2-4 Any disease process that can break down these barriers can induce CME.2-21 Light toxicity from an operating microscope may contribute to free radical release with subsequent prostaglandin synthesis.2-5 Prostaglandins contribute to tissue inflammation, increasing vasodilation and vasopermeability.2 Exogenous prostaglandin analog use in the management of glaucoma has been anecdotally noted to cause CME.2,9,10 This is more prevalent in patients who have undergone incisional ocular surgery with an opened posterior capsule, which, theoretically, allows easier access deep into the eye.2,9,10

|

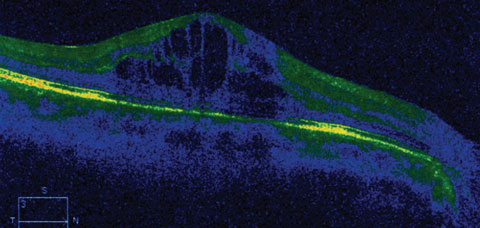

| This OCT image shows an eye with CME following travoprost treatment. Click image to enlarge. |

Pathogenesis

CME is not a diagnosis but a finding occurring from numerous causes; it is named for its intraretinal polycystic petaloid (like the petals of a flower) fluorescein angiographic appearance.1-6 Initiating factors include preservatives in ophthalmic medications, topical prostaglandin analogs, topical beta-blockers, retinal vein occlusion, diabetes mellitus, central serous chorioretinopathy, anterior or posterior uveitis, pars planitis, retinitis pigmentosa, radiation retinopathy, posterior vitreous detachment, epiretinal membrane formation, macular retinal telangiectasia, post YAG laser procedure and blunt trauma.2-18 After cataract surgery, the second most common cause of CME is diabetes.2

Detection

The predominant symptoms caused by CME of any etiology is visual distortion (metamorphopsia) and acuity reduction.2-18 Visual acuity may be minimally affected or significantly reduced.3-18 While the incidence of pseudophakic cystoid macular edema (PCME)-related symptoms (defined as symptomatic vision loss 20/40 or worse) is low (approximately 0.1% to 2.35% of all cases), an estimated 20% to 30% of patients undergoing phacoemulsification demonstrate some form of mild PCME on angiography.4 The rate has been estimated as high as 41% using SD-OCT.3 Fortunately, most patients who have PCME detected only with these tests have no visual disturbances and require no intervention.4

Therapies

When CME is caused by conditions such as diabetes, retinal vein occlusion, retinitis pigmentosa or uveitis, the treatment is dictated by standard-of-care for the causative condition.19-34 Cases of CME arising from diabetic retinopathy or retinal vein occlusion would warrant consideration of focal/laser photocoagulation of the leaking perifoveal capillaries, alone or in combination with injections of anti-VEGF drugs such as bevacizumab, ranibizumab or aflibercept or intravitreal steroid injection implants.

Medications for CME include oral nonsteroidal medicines, such as ibuprofen and indomethacin, and the corticosteroid prednisone. Topical nonsteroidal medications such as ketorolac, nepafenac and bromfenac have also been successful. Topical corticosteroid drops such as prednisolone acetate, loteprednol etabonate and difluprednate can be added for unresponsive or more severe cases.2-5,34,35 Common dosing ranges from QID to Q2H, dictated by severity and symptoms. Duration of therapy may be several days to months.2-18,34,35

Oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) such as acetazolamide and methazolamide have been documented as helpful in recalcitrant cases of CME.36 These agents increase active transport by the retinal pigment epithelium to facilitate fluid movement from the retina through the choroid.36 They work best in cases caused by diffuse retinal pigment epithelial failure (retinal dystrophies).36 Likewise, topical CAIs such as dorzolamide or brinzolamide can also be used.

The majority of cases of symptomatic CME following cataract surgery resolve spontaneously without intervention within eight months, and many cases resolve faster.2-6,34 In rare instances, CME can remain detectable in excess of five years, though patients may not be visually disturbed.2

Upon discovery of the patient’s CME, the topical prostaglandin was replaced by a fixed combination of brimonidine 2%/timolol 0.5%, and bromfenac was initiated. Fortunately, the CME resolved over several weeks and his vision returned to normal.

|

1. Phillips L. After cararact surgery: watching for cystoid macular edema. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Available at www.aao.org/eyenet/article/after-cataract-surgery-watching-cystoid-macular-ed. Accessed Dec. 5, 2016. 2. Fu A, Ahmed I, Al E. Cystoid macular edema. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS. Ophthalmology. Mosby-Elsevier, St. Louis, MO;2009:956-62. 3. Arshinoff SA. Same-day cataract surgery should be the standard of care for patients with bilateral visually significant cataract. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(6):574-9. 4. Guo S, Patel S, Baumrind B, et al. Management of pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015;60(2):123-137. 5. Gass JD, Norton EW. Cystoid macular edema and papilledema following cataract extraction. A fluorescein fundoscopic and angiographic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;76(6):646–61. 6. Trichonas G, Kaiser PK. Optical coherence tomography imaging of macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98 (Suppl 2):ii24-9. 7. Fardeau C, Champion E, Massamba N, LeHoang P. Uveitic macular edema. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2015;38(1):74-81. 8. Sigler EJ. Microcysts in the inner nuclear layer, a nonspecific SD-OCT sign of cystoid macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(5):3282-4. 9. Rosin LM, Bell NP. Preservative toxicity in glaucoma medication: clinical evaluation of benzalkonium chloride-free 0.5% timolol eye drops. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7(10):2131-5. 10. Matsuura K, Sasaki S, Uotani R. Successful treatment of prostaglandin-induced cystoid macular edema with subtenon triamcinolone. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6(12):2105-8. 11. Song SJ, Wong TY. Current concepts in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38(6):416-25. 12. Arevalo JF. Diabetic macular edema: changing treatment paradigms. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(6):502-7. 13. Sarao V, Bertoli F, Veritti D, Lanzetta P. Pharmacotherapy for treatment of retinal vein occlusion. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(16):2373-84. 14. Ahn SJ, Ryoo NK, Woo SJ. Ocular toxocariasis: clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Asia Pac Allergy. 2014;4(3):134-41. 15. Triantafylla M, Massa HF, Dardabounis D, et al. Ranibizumab for the treatment of degenerative ocular conditions. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;24;(8):1187-98. 16. Frisina R, Pinackatt SJ, Sartore M, et al. Cystoid macular edema after pars plana vitrectomy for idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253(1):47-56. 17. Kim JW, Choi KS. Quantitative analysis of macular contraction in idiopathic epiretinal membrane. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14(1):51. 18. Bagnis A, Saccà SC, Iester M, Traverso CE. Cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery in a patient with previous severe iritis following argon laser peripheral iridoplasty. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5(4):473-6. 19. Shah SU, Shields CL, Bianciotto CG, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab at 4-month intervals for prevention of macular edema after plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):269-75. 20. Yu S, Yannuzzi LA. Bilateral perifoveal macular ischemia in sarcoidosis. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2014;8(3):212-4. 21. Pop M, Gheorghe A. Pathology of the vitreomacular interface. Oftalmologia. 2014;58(2):3-7. 22. Rezaei Kanavi M, Soheilian M. Histopathologic and electron microscopic features of internal limiting membranes in maculopathies of various etiologies. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2014;9(2):215-22. 23. Pang CE, Spaide RF, Freund KB. Epiretinal proliferation seen in association with lamellar macular holes: a distinct clinical entity. Retina. 2014;34(8):1513-23. 24. Tsukada K, Tsujikawa A, Murakami T, et al. Lamellar macular hole formation in chronic cystoid macular edema associated with retinal vein occlusion. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55(5):506-13. 25. Lecleire-Collet A, Offret O, Gaucher D, et al. Full-thickness macular hole in a patient with diabetic cystoid macular oedema treated by intravitreal triamcinolone injections. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85(7):795-8. 26. Vujosevic S, Martini F, Convento E, et al. Subthreshold laser therapy for diabetic macular edema: metabolic and safety issues. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20(26):3267-71. 27. Ford JA, Elders A, Shyangdan D, et al. The relative clinical effectiveness of ranibizumab and bevacizumab in diabetic macular oedema: an indirect comparison in a systematic review. BMJ. 2012;345(8):e5182. 28. Giuliari GP. Diabetic retinopathy: current and new treatment options. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2012;8(1):32-41. 29. Pielen A, Feltgen N, Isserstedt C, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravitreal therapy in macular edema due to branch and central retinal vein occlusion: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78538. |