Conjunctivitis is a general term that can refer to any in a spectrum of diseases and disorders that primarily affect the conjunctiva. Patients impacted will present complaining of redness or “pink eye” which is due to dilated conjunctival blood vessels.1 They may also complain of pain, itching or discharge. While most cases are self-limiting and rarely result in vision loss, some may progress and can result in serious ocular complications, and vision loss is not out of the question. For this reason, it’s essential to rule out the sight-threatening causes of red eye.

Additionally, conjunctivitis can stem from different roots, and distinguishing them can help identify treatment options. Conjunctivitis can affect people of any age, demographic group or socioeconomic status.2 We can broadly categorize it as either acute or chronic and either infectious or non-infectious, but within those exist several subclassifications.2

This article provides an in-depth explanation of all the conjunctivitis types you’re likely to encounter—and some that are quite rare. We review the protocol for differential diagnosis and managing each of the possible conjunctivitis cases.2

|

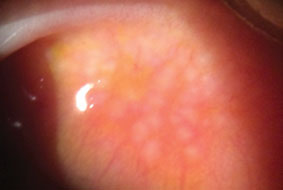

| This patient demonstrates episcleritis, a presentation associated with complaints of discomfort or irritation (rather than true eye pain), redness and edema to the affected area over the sclera. Click image to enlarge. |

Etiology and Epidemiology

Conjunctivitis is the most common cause of eye redness and discharge.2 The three most common types are viral, allergic and bacterial.2 Allergens, toxins and local irritants are responsible for non-infectious conjunctivitis.2

Acute conjunctivitis of all causes is estimated to occur in six million Americans annually.3 The highest rates are among children younger than seven years with the highest incidence occurring between birth and four years.2 Another peak occurs in women at age 22 and men at age 28.4 Overall conjunctivitis rates are slightly higher in women than men.4 Peak seasonal incidence occurs in children in March and in other age groups in May, and this seasonal occurrence is consistent in all geographic regions regardless of changes in climate or weather patterns.4 Allergic conjunctivitis is the most frequent cause, affecting 15% to 40% of the population, and is seen most often in the spring and summer. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis is second most common and its rates are highest from December to April.1,4-7

Viral

Viruses cause up to 80% of all cases of acute conjunctivitis, with many cases misdiagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis.8,9 Between 65% and 90% of viral conjunctivitis (VC) are caused by adenoviruses and they produce the three most common presentations associated with VC; follicular conjunctivitis, pharyngoconjunctival fever and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis.9,10

Follicular conjunctivitis is the mildest form of a viral conjunctival infection. It has an acute onset, initially unilateral with the second eye becoming involved in a week. It presents with a watery discharge, conjunctival redness, follicular reaction and a preauricular lymphadenopathy on the affected side. Most cases resolve spontaneously.10

Pharyngoconjunctival fever is characterized by a high fever that comes on suddenly as well as a sore throat, periauricular lymph node enlargement and a bilateral conjunctivitis.

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, the more severe of the two, presents with an ipsilateral lymphadenopathy, conjunctival redness, swelling and watery discharge.11 Lymphadenopathy is seen in up to 50% of VC cases and is more prevalent in VC than bacterial conjunctivitis.9

Labs and cultures are rarely necessary to confirm bacterial conjunctivitis and is generally reserved for severe or recalcitrant cases.12 In-office rapid antigen testing is available for adenoviruses and can be used to confirm suspected viral causes of conjunctivitis to prevent unnecessary antibiotic use. The Quidel QuickVue (Quidel) adenoviral conjunctivitis test is a rapid, immunochromatographic test for visual, qualitative in vitro detection of adenoviral antigens directly from ocular fluid. A study comparing rapid antigen testing with polymerase chain reaction and viral culture and confirmatory immunofluorescent staining found rapid antigen testing to have an 89% sensitivity and 94% specificity.13

Adenoviral conjunctivitis is highly contagious, with the risk of transmission approximately 50%.14,15 The infection is often termed epidemic keratoconjunctivitis due to the adenovirus’ ability to rapidly infect family members, classmates or co-workers. The virus spreads through direct contact with fingers, swimming pool water and personal items and can be spread for up to 14 days.16-18 With such high transmission rates, hand washing is imperative. One study found 46% of infected individuals had positive cultures grown from swabs of their hands.18 Patients with possible adenoviral infection should be isolated from other patients in the office and all instruments and surfaces must be disinfected after potential exposure.19

While no effective treatment for VC exists yet, supportive measures to help with symptoms include artificial tears, topical antihistamines and cold compresses.12 Available antiviral medications are not useful and topical antibiotics are not indicated.20,21 Povidone iodine—a broad spectrum antimicrobial with high microbial kill rates—can be used in a 5% ophthalmic preparation off-label for management of adenoviral conjunctivitis.22 In fact, a topical ophthalmic suspension of povidone iodine 0.6% and dexamethasone 0.1% is under clinical investigation.23 This medication has the potential to treat both the viral and inflammatory components of adenoviral infection as well as immune-related sequelae such as subepithelial infiltrates.23

|

| Rapid antigen testing, using devices such as this, can prevent unnecessary antibiotic use. Studies show they have high rates of sensitivity and specificity. Click image to enlarge. |

Bacterial

While viral conjunctivitis is more common, bacterial conjunctivitis (BC) can be more of a clinical challenge. It’s the second most commonly occurring infectious cause in a conjunctivitis presentation.5,17 BC is far more common in children than adults, and the pathogens responsible for BC vary depending on the age group. The most common cause of BC in children is Haemophilus influenzae, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis.24 Bacterial infection in adults are more often staphylococcal in origin, with Staphylococcus aureus more commonly found in adults, with an increase in conjunctivitis secondary to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).7 Gram-negative infections are more prevalent in contact lens wearers, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa the most common cause in this group.25 Pseudomonas is also the most likely cause of BC in the critically ill and hospitalized patient.7 Acute BC in newborns is typically the result of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.1

BC can be divided into three clinical presentations: acute, hyperacute and chronic.10 The most common pathogens are the aforementioned Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.10

Signs and symptoms of acute BC include the rapid unilateral onset of a red eye, purulent or mucopurulent discharge, and conjunctival edema. The second eye typically becomes involved one or two days later.10 Bilateral eyelid mattering and eyelids sticking together, a lack of itching, and no history of prior conjunctivitis exposure are strong positive predictors of acute BC.26 Acute BC treatment consists of topical antibiotic drops or ointments. While BC infections are normally self-limiting within one to two weeks of presentation, antibiotic therapy speeds resolution and lessens disease severity.17 A broad spectrum antibiotic may be used for five to seven days. No clinical evidence suggests one antibiotic is better than another.12

Hyperacute BC is most often caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae.27 The disease presents with a severe copious purulent discharge, decreased vision, often eyelid swelling, eye pain on palpation and preauricular adenopathy. The infection carries a high risk if corneal involvement and subsequent corneal perforation.1 Conjunctival cultures are strongly recommended in this presentation. The treatment regimen for gonococcal conjunctivitis includes one gram of intramuscular ceftriaxone. If a corneal ulcer is present, hospitalization with one gram of IV ceftriaxone for three days is recommended.10

Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis is used to describe any conjunctivitis lasting more than three weeks, with Staphylococcus aureus, Moraxella lacunata and enteric bacteria being the most common culprits.10 A chronic staphylococcal conjunctivitis may display signs including a diffuse conjunctival redness with minimal discharge. Papillae or follicles may be present as well as eyelid involvement which may show redness, lash loss, dilated small blood vessels, lid collarettes, recurrent hordeola and may lead to marginal corneal ulcers. The treatment of chronic BC includes antimicrobial therapy and good lid hygiene. Azithromycin drops, erythromycin and bacitracin ointments are effective topical antibiotics. Combination antibiotic/steroid drops or ointments can be rubbed into the lid margins if severe inflammation is present.10 Oral tetracycline-class antibiotics may be needed for more severe presentations.10

|

| This patient is experiencing an allergic reactions on and around the eyelids as well as the conjunctiva. Upon allergen exposure the skin becomes red, tight and itchy. Click image to enlarge. |

Allergic

Ocular allergy is a common condition seen in clinical practice. Allergic disease have dramatically increased in the last decades, with the increase considered to be caused by a number of factors including genetics, increased air pollution in urban areas, pets and early childhood exposure.28-30 Allergic conjunctivitis is a general term encompassing seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC), perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC), vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and atopic conjunctivitis (AKC). Contact lenses or ocular prosthesis associated giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) are often included in this group, yet GPC is not a true allergic disease but a more chronic ocular micro-trauma disorder.31

SAC and PAC are the most common forms of ocular allergies, affecting 15% to 20% of the population.29 Specific IgE antibodies can be documented in almost all cases of SAC and PAC.30 The pathogenesis of allergic conjunctivitis is by and large an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction, where allergens interact with IgE bound to sensitized mast cells, causing degranulation. This mast cell degranulation causes increased levels of histamine, prostaglandins and leukotrienes and also induces activation of vascular endothelial cells, which in turn express chemokines and adhesion molecules. This early-phase reaction clinically lasts 20 to 30 minutes.32 The chemokine release initiates recruitment of inflammatory cells into the conjunctival mucosa, which leads to the late phase allergic reaction, characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells, occurring a few hours after the initial mast cell activation.33

Signs and symptoms are the same in SAC or PAC. SAC is usually caused by airborne pollens occurring in the spring and summer and wane in the winter. PAC occurs throughout the year with exposure to allergens to which the patient is sensitive. Clinical features of both SAC and PAC consist of itching, redness and swelling. Itching is a consistent symptom of both SAC and PAC. An old saying applies here: “If it itches, it’s allergy.” Fortunately, corneal involvement is rare.

Contact allergic reactions usually occur on the skin including the eyelids, but the conjunctiva can also see contact allergic reactions. Upon allergen exposure the skin becomes red, tight and itchy. Treatment includes avoiding contact with the offending agent. Topical and oral antihistamines, topical steroids and cold compresses can help ease the symptoms.

|

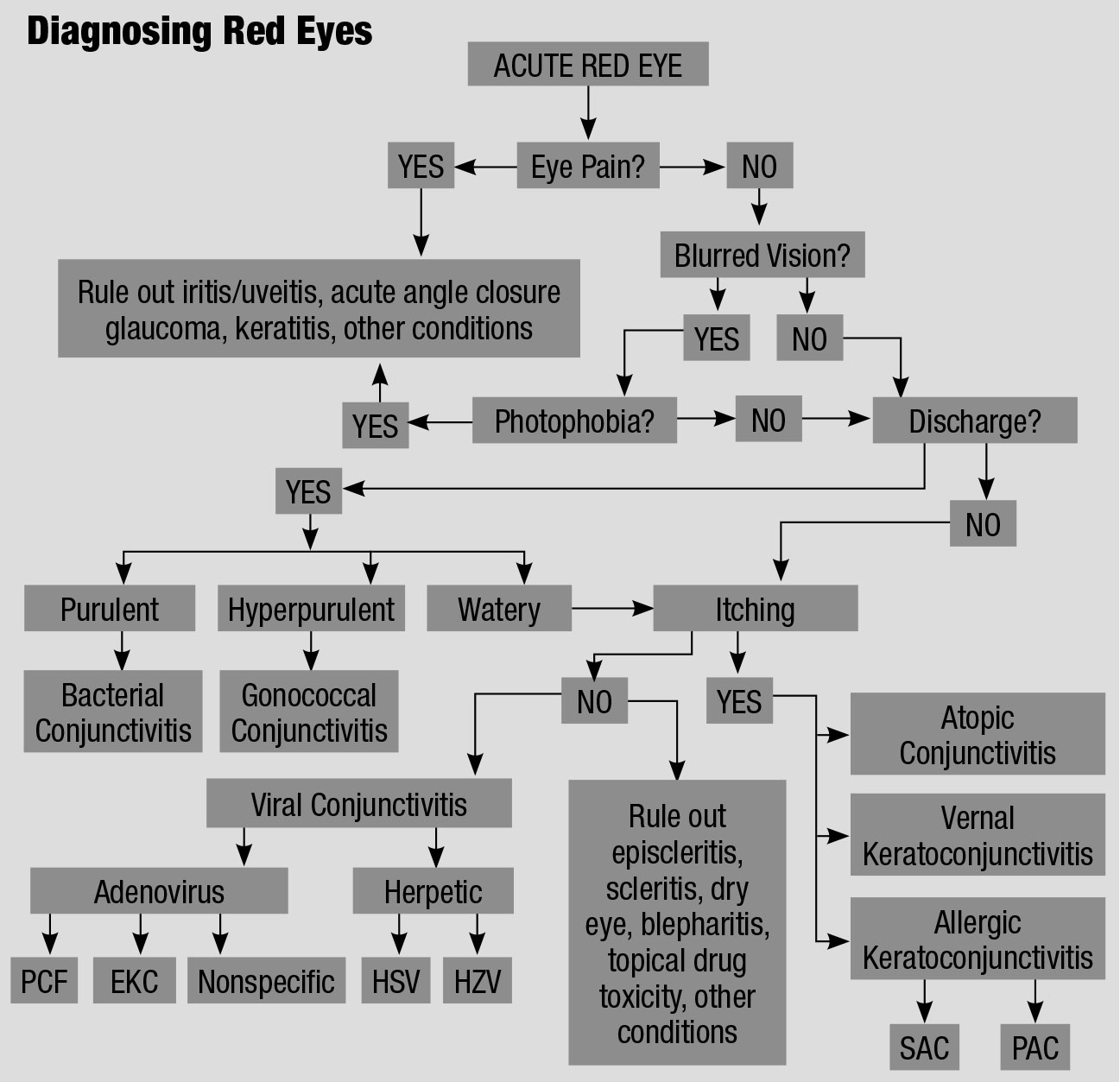

| This flowchart for the differential diagnosis of a red eye, adapted from various sources, explains an orderly approach to treating these irritated patients.61,62 Click table to enlarge. |

Treatment Options for Allergic Conjunctivitis

The first treatment for all types of AC is to avoid the offending allergen if possible, which is difficult if the agent is not readily known. Artificial tears provide a barrier between the offending agent and the conjunctiva, and help dilute and wash away the allergen from the ocular surface.

Keeping the tears refrigerated also provides soothing relief, as do cold compresses. Pharmacologic therapy consists of anti-allergic agents such as antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers and dual-action medications. Due to their short duration of action topical antihistamines require frequent dosing, up to four times daily. Combination antihistamine/decongestants are more effective than antihistamines alone.34 Decongestants are primarily vasoconstrictors and while effective in reducing redness should only be used for short-term relief and are not recommended for use in narrow angle glaucoma patients. Mast cell stabilizers do not relieve existing symptoms and are used prophylactically to prevent mast cell degranulation.

The most commonly used medications for ocular allergy therapy are the multi-action agents that exert multiple pharmacological effects. These include olopatadine, ketotifen, azelastine, epinastine and bepostatine. These medications are the drugs of choice for providing quick symptomatic relief to patients suffering from AC. When these medications do not yield the control desired, the next step are anti-inflammatory agents. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be added to reduce symptoms.

Steroids are the most potent medications used in AC and are effective in treating both acute and chronic presentations.35 Yet as with any medication there are limitations with steroid use, including delayed wound healing, secondary infection, elevated intraocular pressure, and cataract formation. Due to these potential adverse events, a short course of steroid therapy is appropriate. Baseline intraocular lens evaluation and IOP measurements should be taken if an extended steroid course is needed.36

Immunotherapy can be effective in treating the ocular symptoms of AC and may be considered for long term AC control.37 Oral antihistamines are commonly used to treat nasal and ocular allergy symptoms. The newer second generation antihistamines (cetirizine, fexofenadine, loratadine) are preferred as they produce fewer side effects, especially less drowsiness, but they can produce ocular dryness which may actually worsen ocular allergy symptoms, and researchers suggest the concomitant use of topical drops may more effectively treat ocular allergy symptoms.38,39

|

| Giant papilliary conjunctivitis causes this inflammation characterized by papillary hypertrophy of the superior tarsal conjunctiva. Click image to enlarge. |

Vernal

VKC is a disease of warm climates (more common in the tropics) and warm months, but it is not unusual to see the occasional VKC patient in North America.40 Mostly children and young adults, typically males, with a history of atopy are affected.41 Symptoms include ocular itching (which may be quite intense), redness, swelling and discharge. Patients may often have photophobia. The most characteristic signs are giant, “cobblestone” papillae on the upper tarsal conjunctiva, easily seen on lid eversion, with mucous discharge.42

The cornea may be affected in VKC. Trantas dots (clumps of necrotic eosinophils) may appear at the limbus when VKC is active and wane when symptoms subside.33 Noninfectious shield ulcers can present in the superior cornea. Corneal epithelial punctate keratitis may be present and can evolve into corneal macroerosions, ulcers and plaques.28

Atopic

AKC is a bilateral chronic inflammatory disease of the eyelids and ocular surface and the “ocular counterpart” of atopic dermatitis or atopic eczema.42 Ocular findings can include mild to severe conjunctival injection and swelling. Giant papillae and Trantas dots may or may not be present, but conjunctival scarring is common. AKC patients may also develop atopic cataracts and it is not unusual for AKC patients to undergo cataract surgery at a young age.43 Both VKC and AKC may present with giant papillae and Trantas dots. VKC resolves by age 20, while AKC can persist throughout life.33

Giant papillary conjunctivitis

GPC is a conjunctival inflammation characterized by papillary hypertrophy of the superior tarsal conjunctiva similar to VKC but without corneal involvement.33 GPC may be caused by limbal sutures, ocular prostheses and contact lenses.44 Hence, GPC is not a true allergic disease, as the impetus for the papillary conjunctival changes are inert material and not allergens.

Herpetic ConjunctivitisIf your patient’s conjunctivitis isn’t related to the adenovirus, it may one of the nearly 50,000 new or recurring cases of ocular herpes simplex virus (HSV) related conjunctivitis diagnosed in the United States every year.1 HSV comprises 1.3% to 4.8% of all acute conjunctivitis cases.2 You can begin to distinguish it from adenoviral conjunctivitis because HSV is almost always unilateral, whereas adenoviral is usually bilateral.2 In HSV, follicular conjunctivitis, watery discharge and vesicular eyelid lesions may be present.

Unlike adenoviral conjunctivitis treatment, topical and oral antivirals are used to shorten HSV disease duration.3 Topical treatments include trifluridine one percent one drop every two hours, reduced to five time per day after three to seven days, or ganciclovir 0.15% gel five times a day. Oral treatments include acyclovir 400mg three to five times a day in adults, valcyclovir 500mg three times a day, or famciclovir 250mg three times a day.1 Avoid topical steroid use in HSV, as they enhance the virus and can cause harm.4 The virus responsible for shingles, herpes zoster (HZV), is a reactivation of a varicella zoster (chickenpox) infection and can invade ocular tissues, with the eyelids most commonly involved followed by the conjunctiva.5 HZV of the forehead involves the eye in approximately 75% of the cases when the nasociliary nerve is affected.6 Patients presenting with eyelid involvement, or those presenting with vesicles at the end of the nose (the Hutchinson sign), should be examined carefully as HZV is almost always accompanied by ocular involvement. While the Hutchinson sign is a biomarker, it is neither sensitive nor specific, and ocular involvement can occur even if the Hutchinson sign is absent.7 Treatment usually consists of oral antivirals and topical steroids. Topical antivirals have no role in the treatment of HZV. Oral acyclovir can be used, 800mg five times a day, for seven to 14 days. Valacyclovir and famciclovir can also be used. For the treatment of HZV, a good rule of thumb is to double the doses of the medications used for HSV keratitis.7 Oral antivirals started within 72 hours of symptom onset can reduce disease severity and long-term complications.6

|

Episcleritis

Any discussion of the red eye must include episcleritis. This is an acute unilateral or bilateral inflammation of the episclera, the thin layer of loose connective tissue between the conjunctiva and the sclera. Episcleritis can be diffuse, sectoral or nodular, is usually idiopathic and self-limiting, but is sometimes associated with systemic collagen vascular diseases and autoimmune diseases.

An underlying cause is found in about a third of cases.45 These conditions include rheumatoid arthritis, Chron disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, reactive arthritis, relapsing polychrondritis, anklylosing spondylitis, polyarteritis nodosa, Beçhet disease, Cogan syndrome and Wegener granulomatosis.46 Some infections are also linked to episcleritis, including Lyme disease, cat scratch fever, syphilis and herpes virus, but are much less common than the collagen vascular and autoimmune diseases.46

Episcleritis is commonly diagnosed in young to middle-aged females and is rarely diagnosed in children. Patients with episcleritis complain of discomfort or irritation (rather than true eye pain), redness and edema to the affected area over the sclera. Visual acuity is not affected and there is rarely discharge or photophobia. Episcleritis is described as diffuse, where all or part of the episclera is inflamed, or nodular, where the inflammation is confined to an area with the presence of a well-defined, non-mobile, red nodule. Diffuse episcleritis occurs in about 70% of cases, while nodular episcleritis occurs in approximately 30%.47 Nodular episcleritis is often more uncomfortable than a diffuse episcleritis and takes longer to resolve.

The condition is self-limiting, generally running its course in a few days while the nodular form may last for weeks. Many patients may require treatment for the redness and discomfort. Cold compresses and artificial tears provide symptomatic relief. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids are used for persistent symptoms. Rarely, systemic steroids may be necessary. Immunosuppressive treatment to control an underlying autoimmune disorder is the last resort for resistant cases.48 Although episcleritis is usually a benign condition with a good prognosis, there may be some instances where communication with the patient’s rheumatologist is in order.

Conjunctivitis encompasses a wide range of diseases occurring worldwide. It rarely causes permanent vision loss, but its impact on patients’ quality of life can be considerable. It can cause them to miss work or school, not to mention its effect on their wallet.49 Our clinical duty is to properly diagnose and, when necessary, treat this condition, whatever its origin, with a targeted approach.

Dr. Bowling is a past recipient of the Georgia Optometric Association’s Bernard Kahn Memorial Award for outstanding service to the optometric profession.

1. Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013;310:1721-9. 2. Ryder E, Benson S. Conjunctivitis. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019. 3. Sheikh A, Hurwitz B. Topical antibiotics for acute bacterial conjunctivitis: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Practice. 2005;55(521):962-4. 4. Ramirez D, Porco T, Lietman T, et al. Epidemiology of conjunctivitis in US emergency departments. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(10):1119-21. 5. Patel PB, Diaz MC, Bennett JE, et al. Clinical features of bacterial conjunctivitis in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(1);1-5. 6. Alfonso SA, Fawley JD, AlexaLu X. Conjunctivitis. Prim Care 2015;42(3):325-45. 7. Leung A, Hon K, Wong A, et al. Bacterial conjunctivitis in childhood: Etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and management. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2018;12(2):120-7. 8. Fitch C, Rapoza P, Owens S, et al. Epidemiology and diagnosis of acute conjunctivitis at an inner-city hospital. Ophthalmol. 1989;96(8):1215-20. 9. O’Brien T, Jeng B, McDonald M, et al. Acute conjunctivitis: truth and misconceptions. Curr Med Reg Opin. 2009;25(8):1953-61. 10. Rubenstein J, Spektor T. Conjunctivitis: infectious and noninfectious. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019:183-191. 11. Mahood AR, Narang AT. Diagnosis and management of the acute red eye. Emer Clin North Am. 2008;26(1):35-55. 12. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Cornea/External Disease Panel. Conjunctivitis Preferred Practice Pattern. American Academy of Ophthalmology: San Francisco, CA: 2018. 13. Sambursky R, Tauber S, Schippa F, et al. The RPS adeno detector for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis. Ophthalmol. 2006;113(10):1758-64. 14. Udeh B, Schneider J, Ohsfeldt R. Cost effectiveness of a point of care test for adenoviral conjunctivitis. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(3):254-64. 15. Kaufman HE. Adenovirus advances: New diagnostic and therapeutic options. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(4):290-3. 16. Adhikary A, Banik U. Human adenovirus type 8: the major agent of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC). J Clin Virol. 2014;61(4):477-86. 17. Hovding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(1):5-17. 18. Azar M, Dhaliwal D, Bower K, et al. Possible consequences of shaking hands with your patients with epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(6):711-2. 19. Calkavur S, Olukman O, Ozturk A, et al. Epidemic adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis possibly related to ophthalmological procedures in a neonatal intensive care unit: lessons from an outbreak. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19(6);371-9. 20. Skevaki C, Galani J, Pararas M, et al. Treatment of viral conjunctivitis with antiviral drugs. Drugs. 2011;71(3):331-47. 21. Cronau H, Kankanala R, Mauger T. Diagnosis and management of red eye in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(2):137-44. 22. Chronister D, Kowalski R, Mah F, et al. An independent in vitro comparison of povidone iodine and SteriLid. J Ocul Pharmaco Thera. 2010;26(3):277-80. 23. Pepose J, Ahuja A, Liu W, et al. Randomized, controlled phase 2 trial of povidone iodine/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension for treatment of adenoviral conjunctivitis. Am J Opthalmol. 2018;194(10):7-15. 24. Chen F, Chang T, Cavoto K. Patient demographic and microbiology trends in bacterial conjunctivitis in children. J AAPOS. 2018;22(1):66-7. 25. Willcox M, Holden B. Contact lens related corneal infections. Biosci Rep. 2001;21(4):445-61. 26. Rietveld R, ter Riet G, Bindels P, et al. Predicting bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis. BMJ. 2004;329(7459):206-10. 27. Mannus M. Bacterial conjunctivitis. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA (eds.) Duane’s Clinical Ophthalmology. vol. 4. Philadelphia: JB Lippencott; 1990:5.3-5.7. 28. Leonardi A, Motterle L, Bortolotti M, Allergy and the eye. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):17-21. 29. Wong A, Barg S, Leung A. Seasonal and perennial conjunctivitis. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2009;3(2):118-27. 30. Bonini S. Atopic conjunctivitis. Allergy 2004;59(Suppl 78):71-3. 31. Leonardi A, Bogacka E, Fauquert J, et al. Ocular allergy: recognizing and diagnosing hypersensitivity disorders of the ocular surface. Allergy. 2012;87(11):1327-37. 32. Leonardi S, del Gludice Miraglia M, la Rosa M, et al. Atopic disease, immune system, and the environment. Allergy Asthma Proc 2007;28(1-2):410-7. 33. Friedlander M. Ocular allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(5):477-82. 34. Ben-Eli H, Solomon A. Topical antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers and dual-action agent in ocular allergy: current trends. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;18(5):411-6. 35. Pflugfelder S, Maskin S, Anderson B, et al. A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, multicenter comparison of loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5% and placebo for the treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in patients with delayed tear clearance. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(3):444-57. 36. Constock T, Decory H. Advances in corticosteroid therapy for ocular inflammation: loteprednol etabonate. Int J Inflamm. 2012;2012:789623. 37. Starchenka S, Heath MD, Lineberry A, et al. Transcriptome analysis and safety profile of the early-phase clinical response to an adjuvanted grass allergoid immunotherapy. World Allergy Organ J. 2019;12(11):100087. 38. Maziak W, Behrens T, Brasky T, et al. Are asthma and allergies in children and adolescents increasing. Results from ISAAC phase I and phase II surveys in Munster, Germany. Allergy. 2003;58:572-79. 39. Welch D, Osler G, Nally L, et al. Ocular drying associated with oral antihistamines (loratadine) in the normal population – an evaluation of exaggerated dose effect. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;506:1051-5. 40. Kumar S. Vernal conjunctivitis: a major review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:133-47. 41. Vichyanond P, Pacharn P, Pleyer U, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a severe allergic eye disease with remodeling changes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014;25:314-22. 42. Barney NP. Vernal and atopic keratoconjunctivitis. In:Cornea: Fundamentals, Diagnosis and Management, 3rd ed. Krachner JA, Mannus MJ, Holland EJ, eds. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2011:573. 43. Guglielmetti S, Dart J, Calder V. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10(5):478-85. 44. Forister J, Forister E, Yeung K, et al. Prevalence of contact lens-related complications: UCLA contact lens study. Eye Contact Lens. 2009;35(4):176-80. 45. Goldstein D, Tessler H. Episcleritis and scleritis. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier 2009:255-61. 46. Schonberg S, Slokkermans TJ. Episcleritis. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019. 47. Sainz de la Maza M, Molina N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, et al. Clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmol. 2012;119(1):43-50. 48. Salama A, Elsheikh A, Alweis R. Is this a worrisome red eye? Episcleritis in the primary care setting. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(1):46-8. 49. Smith A, Waycaster C. Estimate of the direct and indirect cost of bacterial conjunctivitis in the United States. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009;9:13. |