|

Two recent patients with anterior uveitis underscore new considerations for managing this condition. The first was a 36-year-old man who has had repeated bouts of anterior uveitis in his right eye. Each episode was mild to moderate in intensity, and he responds well to topical steroids and cycloplegia. Well-versed in his symptoms, he readily self-treats with a steroid if he cannot immediately get into the office to be seen. However, he was troubled by the recurrent nature of his condition, which flares up every three to four months. He has had detailed medical evaluations with a rheumatologist who has yet to fund an underlying cause. In an effort to reduce recurrence, his rheumatologist put him on the immunosuppressant agent methotrexate. His rheumatologist communicated that he wanted to ensure there was no clinical evidence of an infectious etiology and to be alerted if the uveitis flared again while the patient was on methotrexate so that he could have justification to put the patient on Humira (adalimumab injection, Abbvie).

The second patient is a 54-year-old man who had been originally referred for evaluation of elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). He had not gotten around to scheduling that appointment, but when he developed a red, increasingly painful left eye, he presented on an emergent basis. He was extremely photophobic and manifested a grade 3 bulbar injection with circumlimbal flush. He also complained of hazy vision in his left eye, though the visual acuity was 20/20 OU. He had a moderate anterior chamber reaction in the left eye with a significant level of flare. No vitritis was seen. He was diagnosed with acute anterior uveitis of the left eye and prescribed generic prednisolone acetate Q1H and atropine BID. He returned for his scheduled follow up and was feeling much better. His ocular redness had disappeared and anterior chamber reaction much dissipated.

He reported that the two medications gave him significant relief on the first day. When asked, he reported that these two generic medications, prednisolone and atropine, cost him $60 and $121, respectively, without insurance.

|

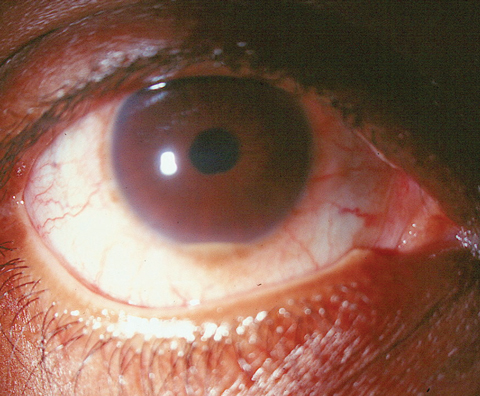

| This 36-year-old patient was troubled about his recurrent hypopyon uveitis flare ups. |

The Basics

Uveitis is most commonly encountered in those between 20 and 60 years old.1,2 Patients typically complain of pain, photophobia and hyperlacrimation. The pain is characteristically described as a deep, dull ache, which may extend to the surrounding orbit. Associated sensitivity to light may be severe, and often these patients will present wearing dark sunglasses. In the earliest stages of anterior uveitis, visual acuity is minimally compromised. Often, patients report that their vision is ‘hazy’ or ‘smoky’ and this represents protein in the anterior chamber (flare). Should the condition persist, or initial treatment delayed, accumulation of cellular debris in the anterior chamber and along the corneal and lenticular surfaces may result in subjectively blurred vision.3,4

Clinical inspection of uveitis patients will reveal a deep perilimbal injection of the conjunctiva and episclera, although the palpebral conjunctiva will remain unaffected. The cornea will display mild stromal edema upon biomicroscopy and, in more severe or protracted reactions, keratic precipitates may be noted on the endothelium. The hallmark signs of non-granulomatous anterior uveitis are cells and flare. Cells represent leukocytes liberated from the iris vasculature in response to inflammation and are observable and freely floating in the convection currents of the aqueous. When present, flare gives the aqueous a particulate, or smoky, appearance. When the inflammation is profound, white blood cells will settle, creating what is known as hypopyon uveitis. Whenever there are sufficient cells in the anterior chamber, convection currents can carry some cells behind the iris into the anterior vitreous. This is termed “spillover” and must be differentiated from an intermediate or posterior uveitis.

Numerous etiologies may induce uveitis, ranging from blunt trauma to widespread systemic infection (e.g., tuberculosis) to generalized ischemic disorders (e.g., giant cell arteritis).5-10 Some other well-known systemic etiologies include ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus, Behçet’s disease, inflammatory bowel syndrome, multiple sclerosis, syphilis, Lyme disease, histoplasmosis and herpetic diseases.5-10

Management

The primary goals in managing anterior uveitis are to: (1) immobilize the iris and ciliary body to decrease pain and prevent exacerbation of the condition; and (2) quell the inflammatory response to avert detrimental sequelae such as maculopathy, cataracts and glaucoma. Cycloplegia is a crucial step in achieving the first goal. Unfortunately, options today are severely limited. With the outright discontinuation of the intermediate potency cycloplegic scopolamine and homatropine not stocked in most pharmacies (obtained through special order in one to two days), practitioners now only have two readily available options: Cyclogyl (cyclopentolate 1%, Alcon) and atropine 1%. Cyclogyl is best used for cycloplegic refractions due to its mild action and short duration; however, it is typically not potent enough to achieve adequate cycloplegia in the inflamed eye and should be avoided.

That only leaves atropine 1%. Many practitioners shy away from this cycloplegic due to its long duration of action. Indeed, in a healthy eye, a drop of atropine will cause mydriasis and cycloplegia for a week or longer. However, in an inflamed eye, this medication needs to be dosed at BID to TID to achieve an adequate therapeutic response.11 Today, practitioners are often forced to choose between a medication which may be too weak and one that may be too strong. We advocate choosing atropine to treat uveitis. Alternately, in-office administration of atropine 1% may give adequate cycloplegia until the patient can obtain homatropine 5%.

Steroids

Numerous steroids can treat anterior uveitis. The most important consideration in choosing which steroid to use is identifying one with the proper potency. Fluorometholone steroids typically are not potent enough for patients with anterior uveitis. Lotemax (loteprednol 0.5%, Bausch + Lomb) is an acceptably potent steroid with a lower propensity (though not negligible) to elevate IOP. For many years, the most commonly used steroid for uveitis management was Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate 1%, Allergan). Cost and insurance often dictate that we use generic prednisolone acetate 1%, which is perfectly acceptable in most cases.

Topical corticosteroids should be administered in a commensurate fashion with the severity of the inflammatory response. In pronounced cases, dosing every 15 to 30 minutes may be appropriate; however, at minimum, steroids should be instilled every three to four hours initially.

In recent years, however, many clinicians have recognized the usefulness of Durezol (difluprednate 0.05%, Alcon) in controlling anterior uveitis.12-14 Clinical trials show that difluprednate 0.05% can be dosed at roughly half the frequency as prednisolone acetate 1% while achieving the same clinical efficacy.11,14 Our successes have made this medication one of our favorite steroids when managing anterior uveitis. We have seen difluprednate manage uveitic conditions that previously failed on other steroids, including Pred Forte.

Recalcitrant cases of anterior uveitis that are unresponsive to conventional therapy may necessitate the use of systemic immunosuppressants such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, interferon or infliximab.15

Only well-trained clinicians who are able to manage complications should prescribe these. In any other case, comanagement with a rheumatologist or internist is a must.

What is Humira?

Humira is a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α blocker. TNF-α is a specific source of inflammation that appears to have a role in uveitis. By blocking it, the inflammatory effect of uveitis is reduced. Uveitis (specifically noninfectious intermediate and posterior uveitis and panuveitis) is the 10th indication for Humira, joining a list that includes rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, pediatric Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa. It appears that rheumatologists are also broadly applying the uveitis indication to anterior uveitis as well.

Cost

Anterior uveitis can be an expensive disease to treat. Branded steroids can run from approximately $130 to $213 per bottle. Whenever possible, we typically use generic medications, but this does not always guarantee an affordable option. Against recommendations, the second patient presented here unfortunately went to the most convenient but expensive pharmacy and ended up paying $180 for two generic medications, whereas he could have had both for about $40 had he gone elsewhere. It behooves practitioners to help patients find the best drug prices and discount coupons using any number of online drug pricing sites. In the case of Humira, rheumatologists need evidence of failure on another immunosuppressant in order to get the medication approved by insurance. Otherwise, Humira therapy will cost upwards of $4,500 per month.

1. Wakefield D, Chang JH. Epidemiology of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45(2):1-13. |