|

Inflammation involves reactions in affected body tissues to stress, injury or other abnormal stimuli. The main reactions in affected body tissues involve vasodilation and increased vasopermeability of the blood vessels that serve the affected tissues. These reactions allow fluid and inflammatory cells to emigrate from the vessels and accumulate in the affected tissues. Vasodilation of existing blood vessels accounts for the redness that an eye may exhibit when injured. In fact, virtually every red eye presentation involves inflammation to some degree.

Cell receptor proteins (present on virtually every cell) are responsible for the effects of corticosteroids. Corticosteroids inhibit inflamma-tory cell access to injured tissues and stabilize cell membranes; this reduces the effects of vaso-dilation and increased vasopermeability.1

Corticosteroids have been one of the most broadly used and effective cate-gories of ophthalmic medication for inflammatory ocular disease. However, there are red eye presentations that appear inflammatory in nature, yet do not respond to corticosteroid therapy. Use of corticosteroids in patients with these conditions offers no therapeutic benefitand it puts the patient at risk for secondary glaucoma, cataracts and super infection.

Here, we will discuss superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) and Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI)two examples of such conditions. We will also discuss the safer alternative treatments for each condition.

Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis

Patients with SLK typically report symptoms of ocular discomfort, including burning and foreign-body sensation. Tearing and photo- phobia have also been reported.

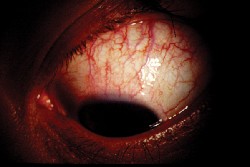

Inspection of the ocular surface in SLK reveals a sectoral inflammation and injection of the superior bulbar conjunctiva. The limbal margin of the cornea may be inflamed as well. A uniform papillary hypertrophy appears along the superior palpebral tarsus. SLK is typically bilateral but often is asymmetric. In most cases, the diagnosis of SLK is made solely on its characteristic presentation.

The exact etiology and pathogenesis of SLK remains unclear, though an autoimmune etiology has been considered. This consideration is based upon exacerbations and remissions, its predominance among females and an associ- ation with autoimmune diseases, such as thyroid disease. Factors such as tight lids, prominent globes and thyroid disease have been offered as potential instigators of this condition.2 The most widely accepted theory regarding the pathogenesis of SLK is that it results from mechanical irritation of the superior limbal region.

|

| Patients who have superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) do not benefit from corticosteroids. |

Surgical recession and surgical resection of the superior bulbar conjunctiva have also been employed as appropriate treatment modalities for SLK. Newer, more effective treatments include punctal occlusion, copious lubrication and topical mast cell stabilizers.2

When managing patients who have SLK, we must remember that this condition has a high association with thyroid dysfunction. As such, we must order the appropriate medical tests and consultations.

Fuchs Heterochromic Iridocyclitis

The typical patient with FHI is a young adult presenting with unilateral vision loss and heterochromia.3-5 However, heterochromia is not an invariable feature, as it may be absent or subtle and unnoticedespecially in dark irides. Busacca and Koeppe nodules are very common but often overlooked iris findings.4 Symptoms typical of acute anterior uveitis, such as pain, photophob- ia, lacrimation and redness, are rarely reported.3,5

Inflammation consisting of mild anterior chamber reaction and fine stellate keratic precipitates are hallmarks of FHI.3,5-7 The keratic precipitates are small to medium and nongranulomatous. Posterior synechiae are not a feature of this condition, though peripheral anterior synechiae are possible and can contribute to glaucoma development. Cataracts and glaucoma are common sequelae of FHI.

While there is no clear consensus regarding the etiology of FHI, various causes including infectious diseases and autoimmunity have all been proposed. Positive associations between FHI and toxoplasmosis, herpes simplex and rubella have also been noted.

Because FHI is indeed an iridocyclitis, corticosteroids seem an intuitive choice of treatment. While anterior chamber reaction and stellate keratic precipitates characterize FHI, this condition is not responsive to corticosteroids in any form.7,8 Correct diagnosis is especially important here so that one is aware of the prognosis and does not attempt ineffective treatments.

Some eyes with FHI receive topical corticosteroid therapy due to a mis-diagnosis of uveitis. Therefore, consider FHI in patients with anterior uveitis that is unresponsive to corticosteroid therapy. In fact, unresponsiveness to topical corticosteroids can actually be a diagnostic sign for FHI.

Glaucoma carries the most risk of significant ocular morbidity in FHI and must be managed aggressively. Aqueous suppressants are indicated, but miotics should never be used. Prostaglandin analogs should only be used when absolutely necessary and should be considered a last medical option. Though glaucoma is inflammatory in nature, visual rehabilitation can be easily accom-plished through cataract extraction with minimal complications. Eyes that have FHI tolerate phacoemulsification with posterior chamber lens implantation well.9,10

Old Infiltrates

Finally, the inappropriate use of corticosteroids on old corneal infiltrates, i.e. inactive, scarred areas that resemble an infiltrative keratopathy, is probably the most common misuse of topical corticosteroids. These lesions occur in asymp-tomatic eyes and tend to be more transparent than true inflammatory infiltrates.

Topical corticosteroids are very potent and a mainstay of management for ocular inflammatory control. But, we must understand that there are conditions, such as the two mentioned above, that appear to be inflammatory in nature, but will not respond to corticosteroid therapy.

1. Charap AD. Corticosteroids. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA., eds. Duanes foundation of clinical ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1992: Chapter 31.

2. Kabat AG. Lacrimal occlusion therapy for the treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Optom Vis Sci 1998 Oct;75(10):714-8.

3. Fearnley IR, Rosenthal AR. Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis revisited. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1995 Apr;73(2):166-70.

4. Jones NP. Fuchs heterochromic uveitis: a reappraisal of the clinical spectrum. Eye 1991;5 (Pt 6):649-61.

5. La Hey E, Baarsma GS, De Vries J, et al. Clinical analysis of Fuchs" heterochromic cyclitis. Doc Ophthalmol. 1991;78(3-4):225-35.

6. Arellanes-Garcia L, del Carmen Preciado-Delgadillo M, Recillas-Gispert C. Fuchs" heterochromic iridocyclitis: clinical manifestations in dark-eyed Mexican patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2002 Jun;10(2):125-31.

7. Gordon L. Fuchs heterochromic cyclitis: new clues regarding pathogenesis. Am J Ophthalmol 2004 Jul;138(1):133-4.

8. Jones NP. Fuchs heterochromic uveitis: An update. Surv Ophthalmol 1993 Jan-Feb;37(4):253-72.

9. Cheng B, Liu Y. Phacoemulsification in eyes with Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis. Yan Ke Xue Bao 2000 Jun;16(2):97-8.

10. Budak K, Akova YA, Yalvac I, et al. Cataract surgery in patients with Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1999 Jul-Aug;43(4):308-11.