With ocular trauma, a relatively innocuous presentation can be associated with a significant injury, and symptoms can often be more pronounced than the actual injury itself. When evaluating a traumatic ocular injury, quickly discerning whether it is penetrating or non-penetrating is critical, as the former requires prompt intervention to reduce the risk of endophthalmitis. This four-step approach can help ensure patients get prompt care:

Step One: History and Exam

This is key to rule out significant trauma. The patient pictured here was hammering metal on metal, which creates a small, high-velocity projectile that can easily penetrate the globe. Although sharp trauma is generally associated with a higher incidence of globe penetration, blunt trauma can also cause globe rupture around surgical incisions or where the sclera is most thin, near insertion of the rectus muscles. Thus, either form of trauma to a previously operated eye increases the index of suspicion for a ruptured globe.

Risk factors for open globe include: (1) vision worse than 20/200; (2) relative afferent pupillary defect; (3) hemorrhagic chemosis; (4) vitreous hemorrhage; and (5) relative hypotony. For this patient, we ordered a computed tomography scan to confirm an intraocular foreign body (IOFB).

Step Two: Alert the Team

An IOFB constitutes a true emergency because of the risk of traumatic endophthalmitis and requires an immediate referral to the surgeon and a local retina specialist. If the patient develops an infection associated with a traumatic injury, the bacteria can be virulent and cause severe damage. Therefore, foreign body injuries require prompt treatment to avoid a potentially disastrous outcome.

|

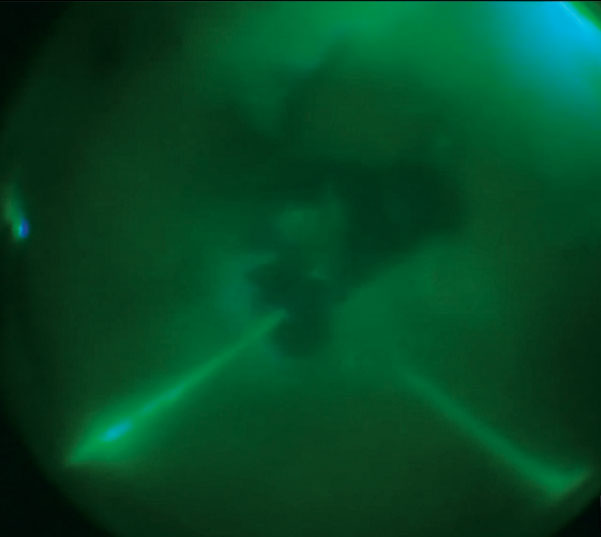

| Using a digital red-free filter to see through the vitreous blood, the surgeon was able to tamponade the blood and create a better view of posterior segment damage, including the IOFB. |

Step Three: Surgery

Management of significant trauma can be challenging. In this case, the patient had many complications: corneoscleral laceration, dense hyphema and vitreous hemorrhage, traumatic cataract, IOFB and traumatic retinal detachment (RD) with two retinal impact sites. We chose a two-stage surgical approach. In the first surgery, we repaired the laceration, removed the lens and injected intravitreal and subconjunctival antibiotics. During the second repair, we washed out the anterior segment blood, removed the vitreous hemorrhage, repaired the RD, stabilized the posterior impact sites, removed the IOFB and reinjected antibiotics.

Often, visualization during the primary repair is significantly compromised, and a fresh wound may not be able to hold the pressure required for vitrectomy surgery and foreign body removal. High-resolution digitally assisted vitreoretinal surgery was critical in this case, as the digital filters suppressed the vitreous blood, enabling a better view and permitting more precise and less traumatic IOFB and bloody vitreous removal. Moreover, the enhanced depth of field helped us achieve a relatively atraumatic foreign body removal.

Step Four: Follow up

Over the first post-op week, comanaging clinicians must ensure the globe remains formed and free of infection. Typically, frequent antibiotic drops and anti-inflammatory steroids are prescribed in addition to oral antibiotics. After the first week, patients are monitored for recurrent hemorrhage, RD and abnormal intraocular pressure.

Newer technologies and techniques have refined our approach to severe trauma, and today’s patients can achieve a functional outcome despite significant injuries.