I had a patient with uveitis of unknown etiology, which turned out to be Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome. In the future, when should I think about comanaging uveitis?

I had a patient with uveitis of unknown etiology, which turned out to be Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome. In the future, when should I think about comanaging uveitis?

“Panuveitis with associated neurological symptoms should always be comanaged with a retinal or uveitis specialist due to the threat of vision loss and, even worse, death from an underlying systemic infection,” says Kristen Spears, OD, of Omni Eye Services, in Atlanta.

Dr. Spears recently had a case with a very similar presentation. The patient was a 35-year-old male of Indian descent whose chief complaint was progressive blurry vision over the prior four to six weeks. “Upon further questioning, he complained of eye pain and ringing in his ears that had started one week before,” Dr. Spears says.

|

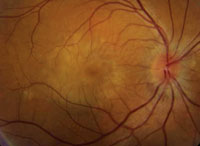

| One clue to VKH: a “sunset glow” fundus. |

“An infectious etiology was at the top of my list of differentials, but the lack of systemic symptoms really threw me off,” Dr. Spears says. “The signs that led me to suspect Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome were his hearing loss and bilateral serous detachments. My first thought was that he needed a strong dose of oral prednisolone, but because of the potential for an infectious etiology, I knew I needed the help of a specialist.”

Fortunately, a retinal specialist was available at Omni. “Had I been in a private practice, I would have started the patient on topical therapy—with a corticosteroid, atropine and phenylephrine—ordered extensive blood work that day, and sent the patient to a retinal or uveitis specialist right away,” she says.

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome is a rare systemic disease involving various melanocyte-containing organs. There are four distinct stages of the disease: prodromal, acute uveitic (Dr. Spears’ patient presented at this stage), convalescent and chronic recurrent. VKH is more common in Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic and Native American populations.1

The hallmark ocular signs are bilateral serous retinal detachments, panuveitis and a “sunset glow” fundus. VKH is highly correlated with the HLA-DR4 haplotype and many other antigens associated with autoimmune diseases.

“We ran a battery of lab tests on this patient, including a complete blood count, rapid plasma reagin, FTA-ABS, angiotensin-converting enzyme, purified protein derivative, chest X-ray, and checked for multiple HLA haplotypes,” Dr. Spears says. “The only significant finding from his lab testing was the presence of the HLA-DR4 antigen. But, that combined with his presentation and case history is about as diagnostic as you can get for VKH.”

The retinal specialist agreed with the diagnosis, and prescribed 20mg oral prednisolone five times a day, Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate 1%, Allergan) every hour and homatropine 5% TID. The specialist saw him again four days after his first visit and weekly thereafter for two months.

Regarding follow-up, “optometrists should see these patients every one to two months for the first nine months after discontinuing the oral steroids. Biannual visits are sufficient after that,” she says. “Be sure to educate patients with VKH about their increased risk for glaucoma, cataracts and development of neovascularization.”

Her patient is doing well now. “The patient had an incredibly successful recovery,” Dr. Spears says. “His vision improved from 20/400 OD, OS, to 20/25 OD, OS, during the course of a 40-day treatment. His hearing also returned within that time period. We’re still seeing him monthly and expect him to continue to do well.”

1. Sakata VM, da Silva FT, Hirata CE, et al. Diagnosis and classification of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 April - May;13(4-5):550-5.