|

History

A 66-year-old Caucasian male presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of lost vision in the right eye. He explained that he woke up with poor vision three days prior but couldn’t get anyone to take him to the hospital. As his vision worsened and it became clear he could no longer function, he called the police, who brought him to the emergency department.

His systemic history was positive for hypertension. His ocular history was remarkable for strabismic amblyopia and corrective muscle surgery in his left eye.

He also recounted that the vision in his left eye was habitually poor since childhood, because of a lazy, crossed eye.

He denied using any medications and reported no known allergies.

Diagnostic Data

His best uncorrected entering visual acuity was no light perception in his right eye and 20/400 OS at distance and near. Pupil testing uncovered a grade IV afferent defect in the right eye. Extraocular muscle movements were full and unrestricted in both eyes with orthophoric position. Confrontation fields were full in all fields of gaze, in the left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed normal and healthy anterior segment structures with no evidence of iris neovascularization in the left eye, with both anterior chambers observed as deep and quiet.

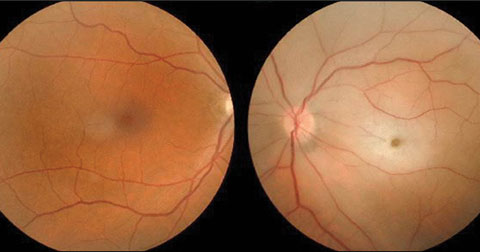

Intraocular pressures measured 18mm Hg OU. The pertinent dilated fundus findings are demonstrated in the photograph.

Your Diagnosis

Does this case require additional tests? What does this patient’s history tell you about his likely diagnosis? How would you manage this patient?

Discussion

Laser interferometry, under patched conditions was completed to ensure NLP status. The fundi were photodocumented. Laboratory tests were ordered in an attempt to uncover the underlying cause such as coagulopathy, hyperviscosity, dyslipidemia, cardiac disease, valvular disease, infectious disease, inflammatory disease, autoimmune disease and carotid artery disease including a complete blood count with differential and platelets (CBC with Diff and platelets), prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT ), lipid panel and carotid Doppler.

|

| This 66-year-old patient presented to the emergency department with vision loss in the right eye. Can this image combined with his medical history help diagnose him? |

The diagnosis in this issue was ophthalmic artery occlusion, in the right eye. Unfortunately, because the patient failed to react promptly, the damage done by more than 72 hours of ischemia to all structures distal to the blockage was not treatable or reversible. The focus became identifying the underlying cause with the goal of arresting or reversing potential mortal disease processes (cerebral vascular accident and myocardial infarction).

The ophthalmologic management for retinal and ophthalmic vein occlusion must take place within 70 minutes to offer hope. Two approaches can be used in concert:

- Decrease the IOP in an attempt to reduce the resistance for retinal arterial perfusion using fast-acting, topical, oral or surgical modalities, such as topical beta blockers, topical apraclonidine, oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, oral hyperosmotic preparations and parecentisis.

- Activate retinal autoregulatory mechanisms in an attempt to increase vascular diameter, thereby allowing the embolis to pass via aggressive digital ocular massage with or without increasing blood carbon dioxide levels via rebreathing into a paper bag or using carbogen (A 95% oxygen, 5% carbondioxide mixture).1,2

Elements of systemic vascular disease that ultimately contribute to increasing the risk of arterial occlusion include coagulopathy, hyperviscosity, dyslipidemia, cardiac disease, cardiac valvular disease and carotid artery disease.2,3 Systemic testing with the goal of aborting life-altering catastrophic outcomes is an essential component of the management of this ocular condition.2,3 In cases potentially involving giant cell arteritis, temporal artery biopsy is the standard method of defintive diagnosis with medical treatment consisting of intravenous methylprednisone administration.

Some evidence suggests that thrombolysis, using deliverable injected compounds could offer a beneficial effect in retinal arterial occlusion.4 However, this approach carries the risk of inducing hemorrhage.4 Investigators hypothesize that retrograde cannulation of the supraorbital arteries followed by irrigation with fibrinolytic agents may have the potential to minimize the risk of major complications while offering sight saving benefits.4 According to one study, the supratrochlear artery appears to provide the most reliable local access route.4

Urokinase has also been selectively studied as an agent that can be infused into the ophthalmic artery as an emergency treatment for combined central retinal arterial obstruction and central retinal venous obstruction.5

Researchers have found limited success for this otherwise unmanageable condition which, when no treatment is proffered, results in certain poor visual outcomes. Urokinase has few systemic complications, but it may cause intravitreal hemorrhage.5

|

1. Rumelt S, Brown GC. Update on treatment of retinal arterial occlusions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2003;14(3):139-41. 2. Schmidt D. Ocular massage in a case of central retinal artery occlusion the successful treatment of a hitherto undescribed type of embolism. Eur J Med Res 2000;19;5(4):157-64. 3. Yamamoto T, Mori K, Yasuhara T et. al. Ophthalmic artery blood flow in patients with internal carotid artery occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(4):505-8. 4. Schwenn O, Wustenberg E, Konerding M, et. al. Experimental percutaneous cannulation of the supraorbital arteries: implication for future therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(5):1557-60. 5. Vallee J, Paques M, Aymard A. Combined central retinal arterial and venous obstruction: emergency ophthalmic arterial fibrinolysis. Radiology. 2002;223(2):351-9. |