In April 2016, optometry lost a giant when the author of the seminal work Primary Care of the Posterior Segment, Larry Alexander, OD, died. In addition to being an optometric physician, author and educator at the University of Alabama Birmingham School of Optometry, Dr. Alexander was a past president of the Optometric Retina Society (ORS). That group has chosen to honor his legacy by accepting case reports from optometric residents across the country relating to vitreoretinal disease. The contest is sponsored by Optovue, Zeiss, Heidelberg and Optos.

As selected by the board of the ORS, this case was a co-winner of the fourth annual Larry Alexander Resident Case Report Contest.

|

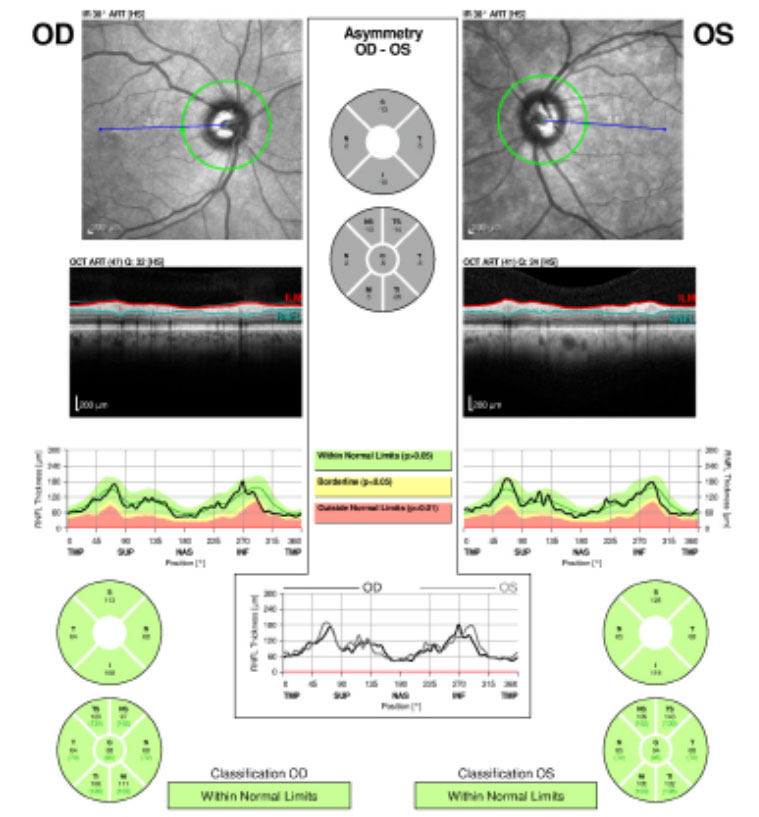

| Fig.1. The patient’s retinal nerve fiber layer analysis at presentation shows no glaucomatous thinning for both eyes. Click image to enlarge. |

Nevus of ota is a hyperpigmentation of the ocular adnexa and globe. Patients with this condition are usually of Asian descent and it rarely occurs in Caucasians. This report features a 71-year-old Caucasian male with nevus of ota who presented with a choroidal mass in his left eye. Clinical features of the mass include a dome-shaped elevation with indistinct borders and orange pigment spots overlying the surface. Evaluation with B-scan and optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed the elevation and underlying subretinal fluid.

This is a rare case of a Caucasian patient with nevus of ota that progressed into a primary choroidal melanoma. Here we also discuss the advanced management and treatment.

|  |

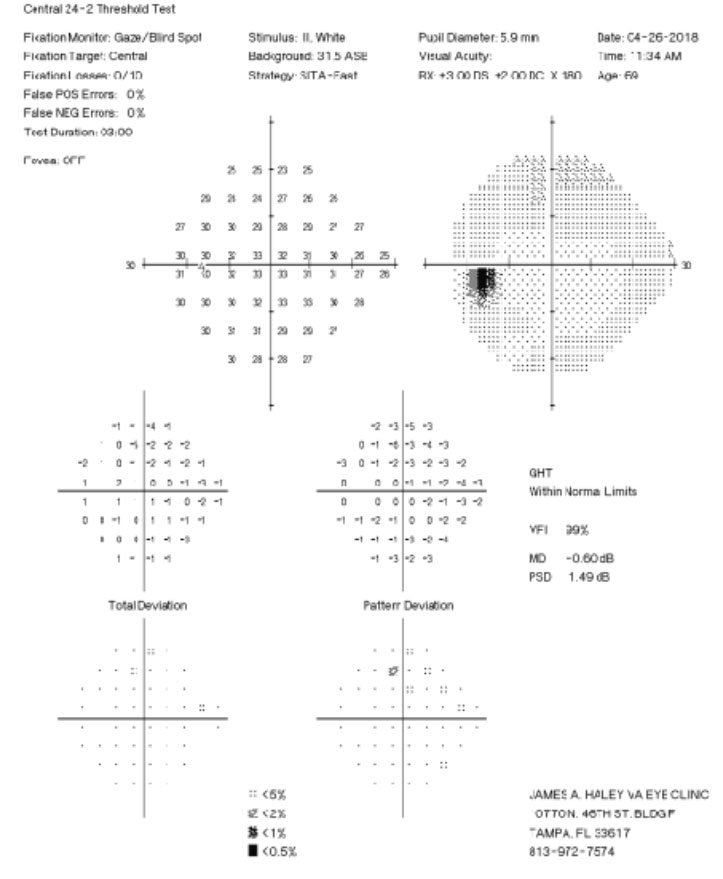

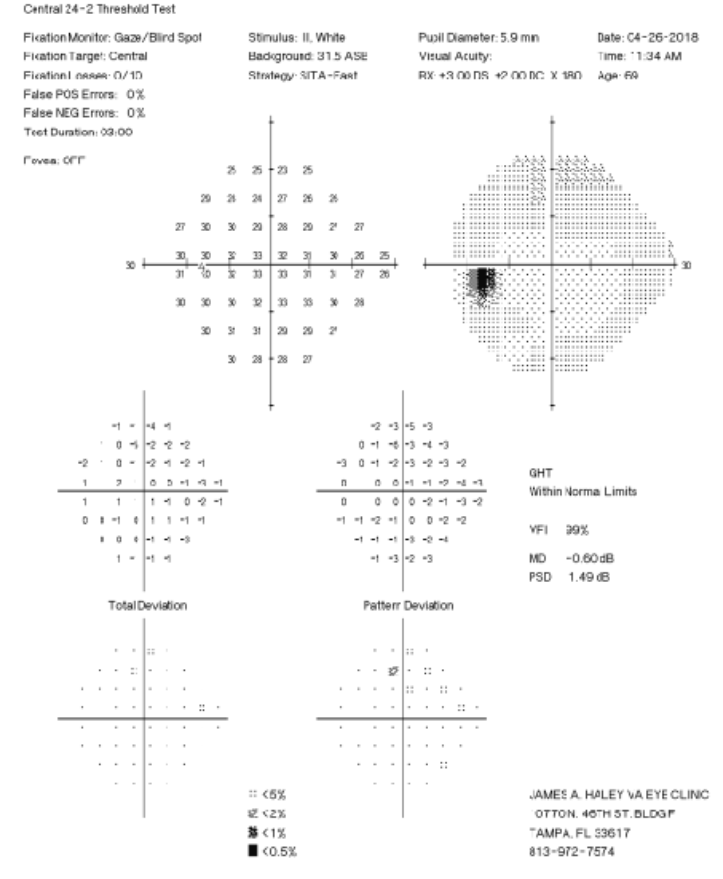

| Fig. 2. His 24-2 visual fields the year prior show no glaucomatous visual field defects. Click image to enlarge. | |

Background

Nevus of ota, also known as oculodermal melanocytosis, was first reported by Hulke in 1860. Later in 1939, Ota and Tanino described the findings as a unilateral, patchy, grey and irregular discoloration of the skin supplied by the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve.1 Nevus of ota affects 0.014% to 0.034% of the Asian population, with incidence highest in individuals of Japanese descent affecting 0.2% to 1%.2,3 Explanation for this higher incidence in the Japanese population is unknown. Nevus of ota rarely occurs in Caucasians, affects women more than men and is typically present at birth but can appear during puberty or pregnancy.2 Nevus of ota occurs unilaterally in 90% of the cases, with incidence of bilateral involvement as low as 1.4%.4,5

Ophthalmic complications associated with nevus of ota include open-angle glaucoma (10%), cataracts and development of a primary choroidal melanoma (4%) that is usually ipsilateral to the side of the nevus of ota.1,4,6

|

| Fig. 3. The patient’s left upper and lower eyelids show visible areas of dermal pigmentation. The left temporal, nasal, superior and inferior bulbar conjunctiva also shows similar areas of pigmentation. The iris color was noted to be blue in the right eye and brown in the left eye (iris heterochromia). Click image to enlarge. |

The diagnosis of nevus of ota is usually made clinically. Physical exam reveals a unilateral, patchy, hyper-pigmented lesion following the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve, especially within the periorbital region.1Differential diagnosis for nevus of ota includes café-au-lait patch, spilus nevus and acquired bilateral nevus of ota-like macules.2 Acquired bilateral nevus of ota, also known as Hori’s nevus, appears later in life in the third to fourth decade and has no known associated ophthalmic associations.7

Systemic conditions associated with nevus of ota include Sturge-Weber syndrome, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, neurofibromatosis, multiple hemangiomas, spinocerebellar degeneration and ipsilateral deafness.1

|

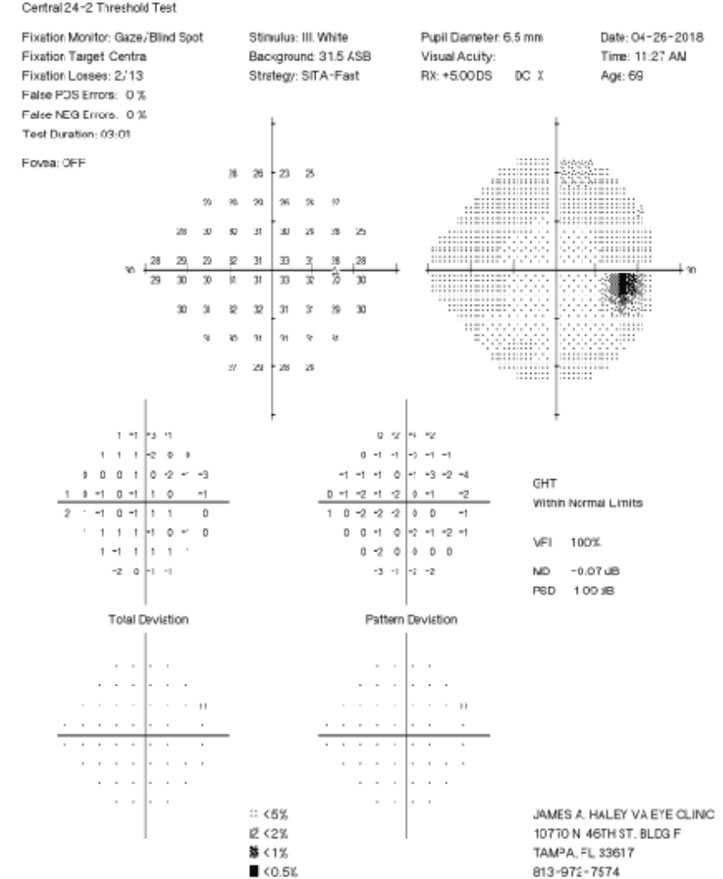

| Fig. 4. The right (top) and left (bottom) macular scans show normal foveal contour without evidence of fluids. Click image to enlarge. |

Case Report

A 71-year-old white male presented to our clinic for his annual eye examination with no complaints. The patient’s past medical history was positive for coronary artery disease, benign prostatic hyperplasia, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and Crohn’s Disease. His past ocular history included suspicion for glaucoma due to a moderate cup-to-disc ratio in both eyes with previously normal retinal nerve fiber layer using OCT and full 24-2 visual fields (Figures 1 and 2).Systemic medications included aspirin 81mg daily, terazosin 2mg daily, atorvastatin 10mg daily, omeprazole 20mg twice daily, finasteride 5mg daily and tramadol 50mg twice daily. His ocular medications included preservative-free artificial tears twice daily in both eyes. The patient has no known drug allergies and was oriented to time, place and person. He denied smoking, illegal drug use and alcohol consumption.

|

| Fig. 5. Fundus photos of the right eye reveal a 0.75-disc diameter flat choroidal nevus in the superior-temporal arcade region (red arrow). The pigment appearance temporally and inferiorly is an artifact from the fundus camera. Click image to enlarge. |

His best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 at distance and near in both eyes. Pupils were equally round and reactive to light without an afferent pupillary defect. Confrontation visual fields were full to finger counting in both eyes. Extraocular muscles were unrestricted in all gazes and cover test demonstrated orthophoria at distance and near. Intraocular pressures were 17mm Hg in the right eye and 16mm Hg in the left eye at 10:47am.

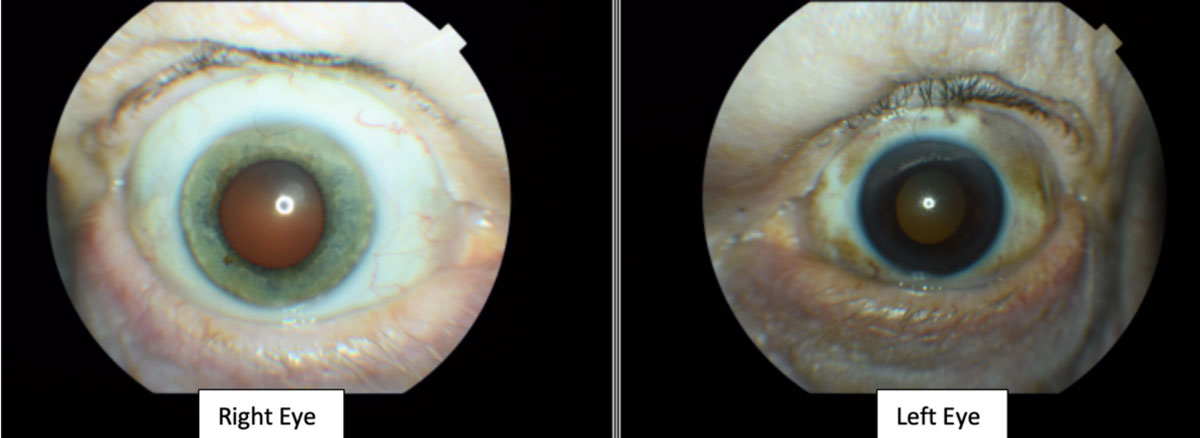

The slit lamp examination revealed bilateral upper eyelid dermatochalasis. The left upper and lower eyelids showed visible areas of dermal pigmentation. The left temporal, nasal, superior and inferior bulbar conjunctiva also showed similar areas of pigmentation (Figure 3). The right eyelid and right bulbar conjunctiva lacked similar pigmentation and appeared normal.

The corneas were clear in both eyes. The iris color was noted to be blue in the right eye and brown in the left eye. The anterior chamber appeared clear without cells or flare and the estimate of the anterior chamber angles were open nasally and temporally by Von Herrick technique.

|

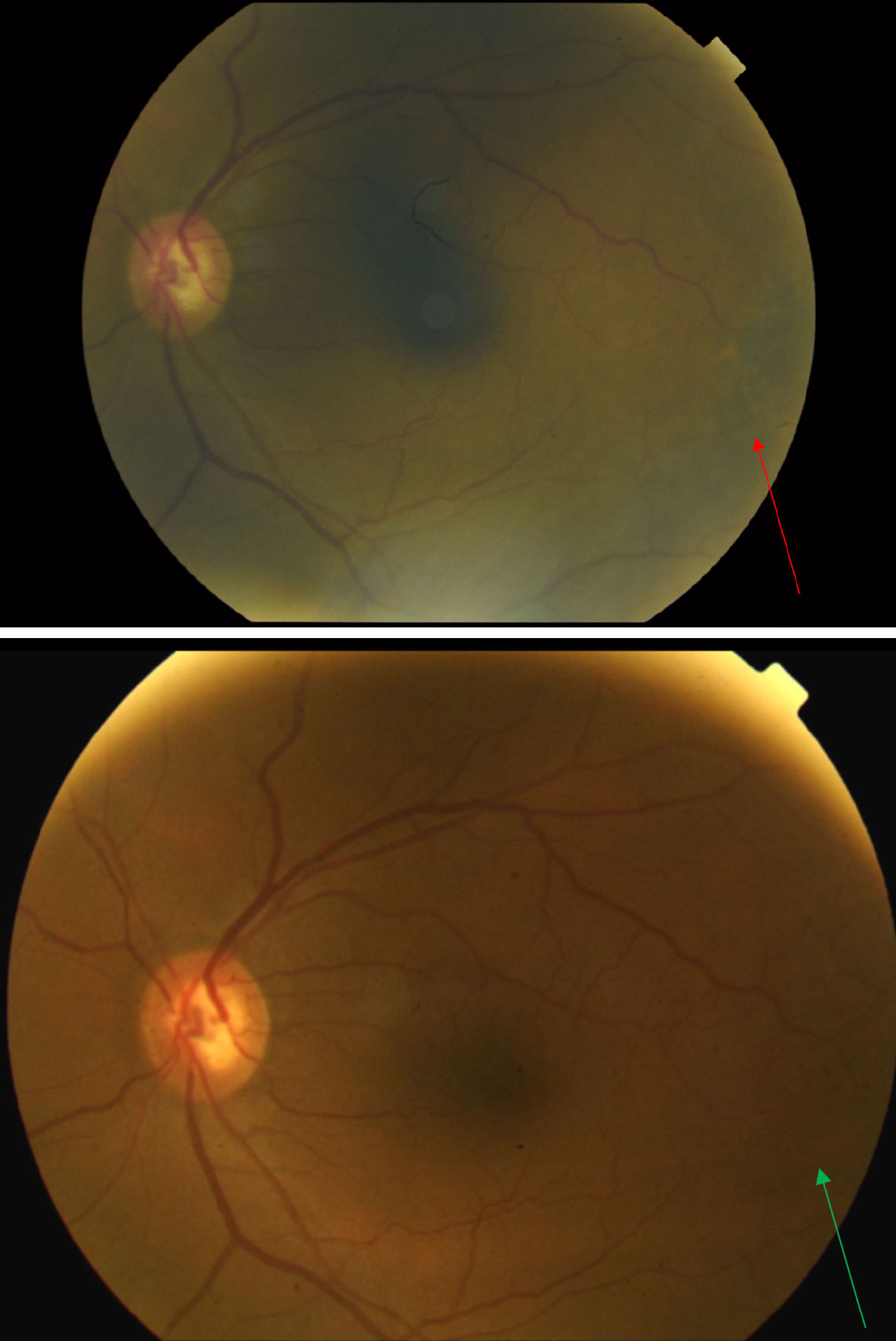

| Fig. 6. Fundus photo of the left eye taken at presentation (top) reveals pigmentary changes temporal to the macula (red arrow). When compared with the fundus photo of the same left eye taken nine years earlier (bottom) one can see the progression of pigmentary changes over the years (green arrow). Click image to enlarge. |

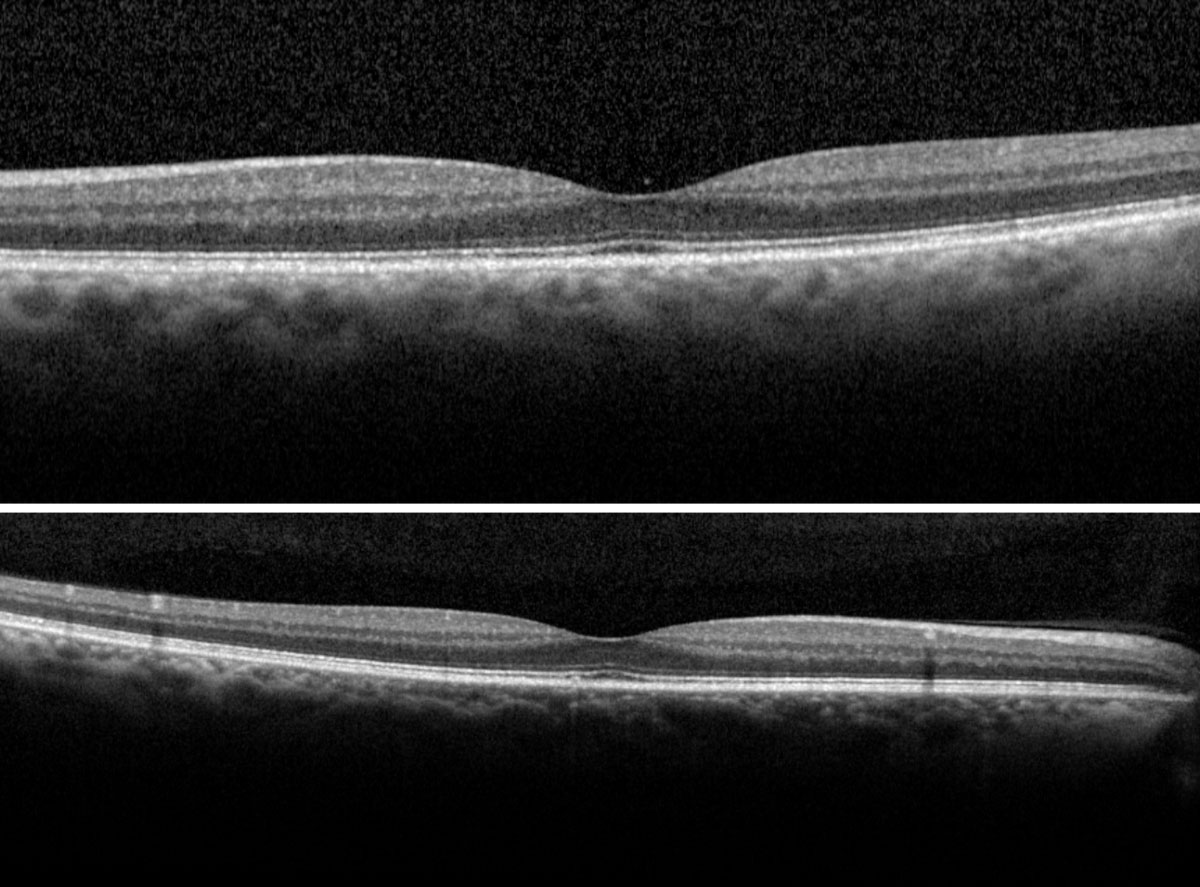

The dilated exam by slit lamp with a 90D lens and by binocular indirect ophthalmoscope with a 20D lens revealed trace nuclear cataracts in both eyes with clear vitreous media bilaterally. Fundus assessment revealed large optic nerves with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.5v/0.5h right eye and 0.7v/0.7h left eye. The neuroretinal rims were healthy and intact. Retinal vessels appeared normal with an arterial-venous ratio of 2/3 noted bilaterally. Both eyes presented with trace macular drusen without evidence of hemorrhages or thickening (Figure 4).

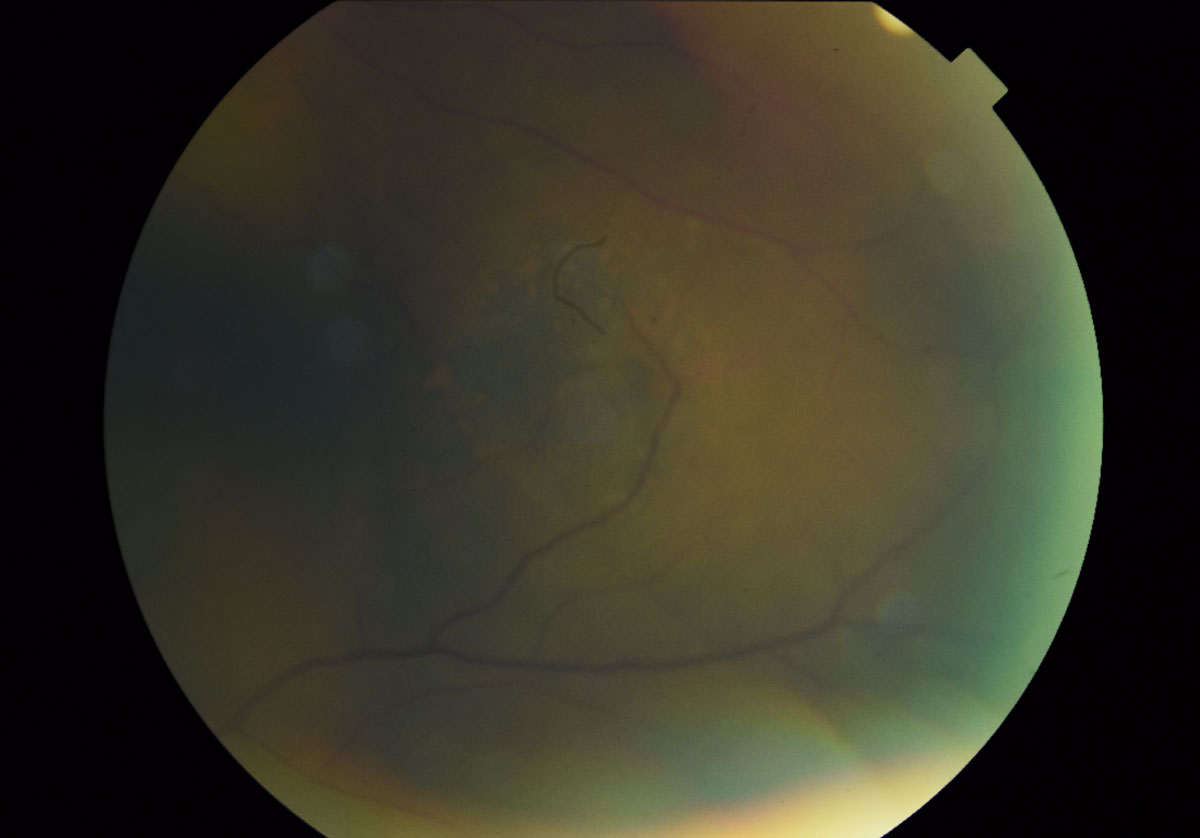

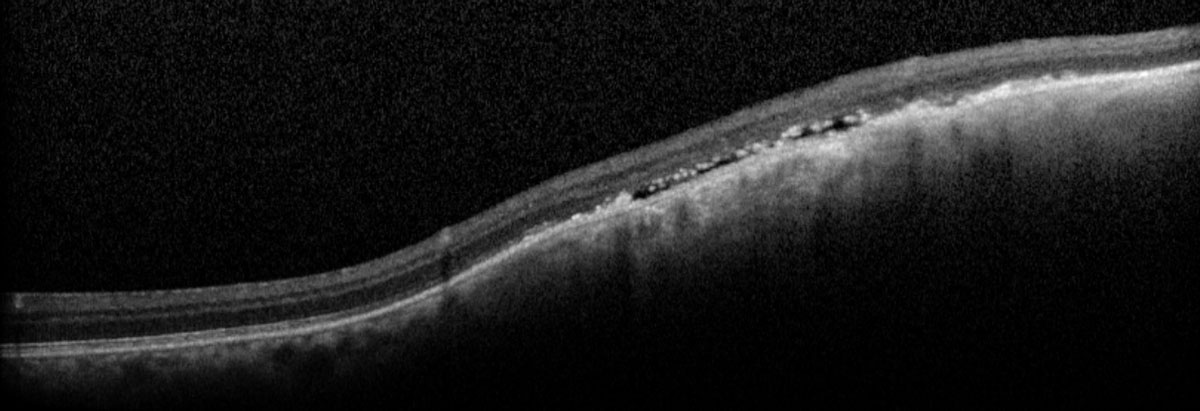

The posterior pole of the right eye had a 0.75-disc diameter flat choroidal nevus in the superior-temporal arcade region (Figure 5). The left eye had a 5- to 6-disc diameter dome-shaped lesion in the mid-peripheral arcade temporal to the macula (Figures 6 and 7). This dome-shaped lesion in the left eye appeared to have orange pigment spots on the surface with an absence of drusen and halo, as well as overlying sub-retinal fluid (Figure 8). When compared with the fundus photos taken nine years prior, there are clear changes in the progression of the lesion.

The peripheral retina was flat and intact with no evidence of tears and breaks in both eyes. Additional testing was done to further investigate the lesion in the left eye.

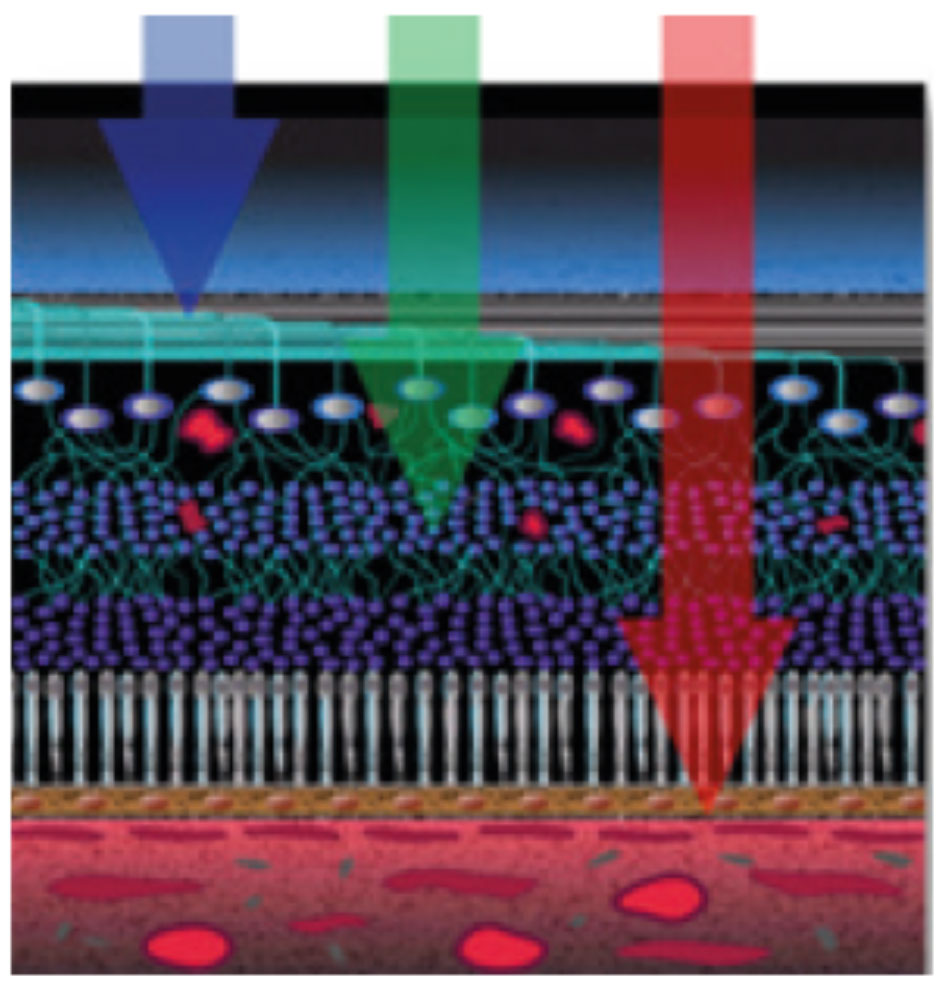

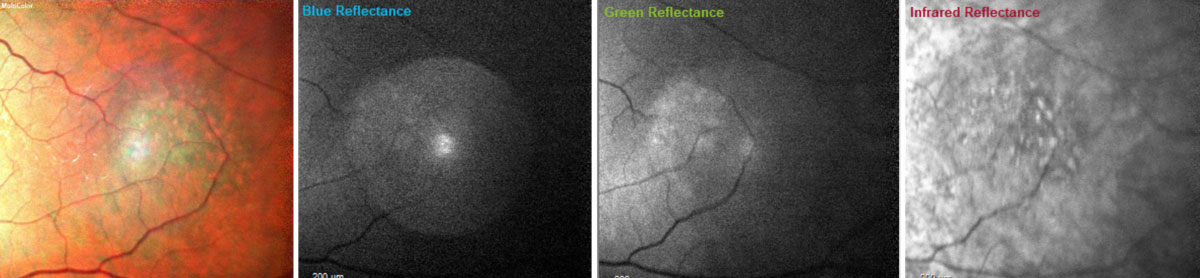

Using the multicolor image feature of the Heidelberg OCT, the orange pigment spots as well as the irregular borders on the dome-shaped lesion in the left eye became more apparent (Figures 9 and 10).8

The patient was diagnosed with nevus of ota, even though this condition is exceedingly rare in a Caucasian patient. is extremely rare. The patient had developed a highly suspicious choroidal mass in the left eye, presumably a primary intra-ocular melanoma, given the abnormal clinical characteristics. An immediate consult to the retinal oncologist was placed to discuss treatment and management options.

Follow up 1: With Retinal Oncologist

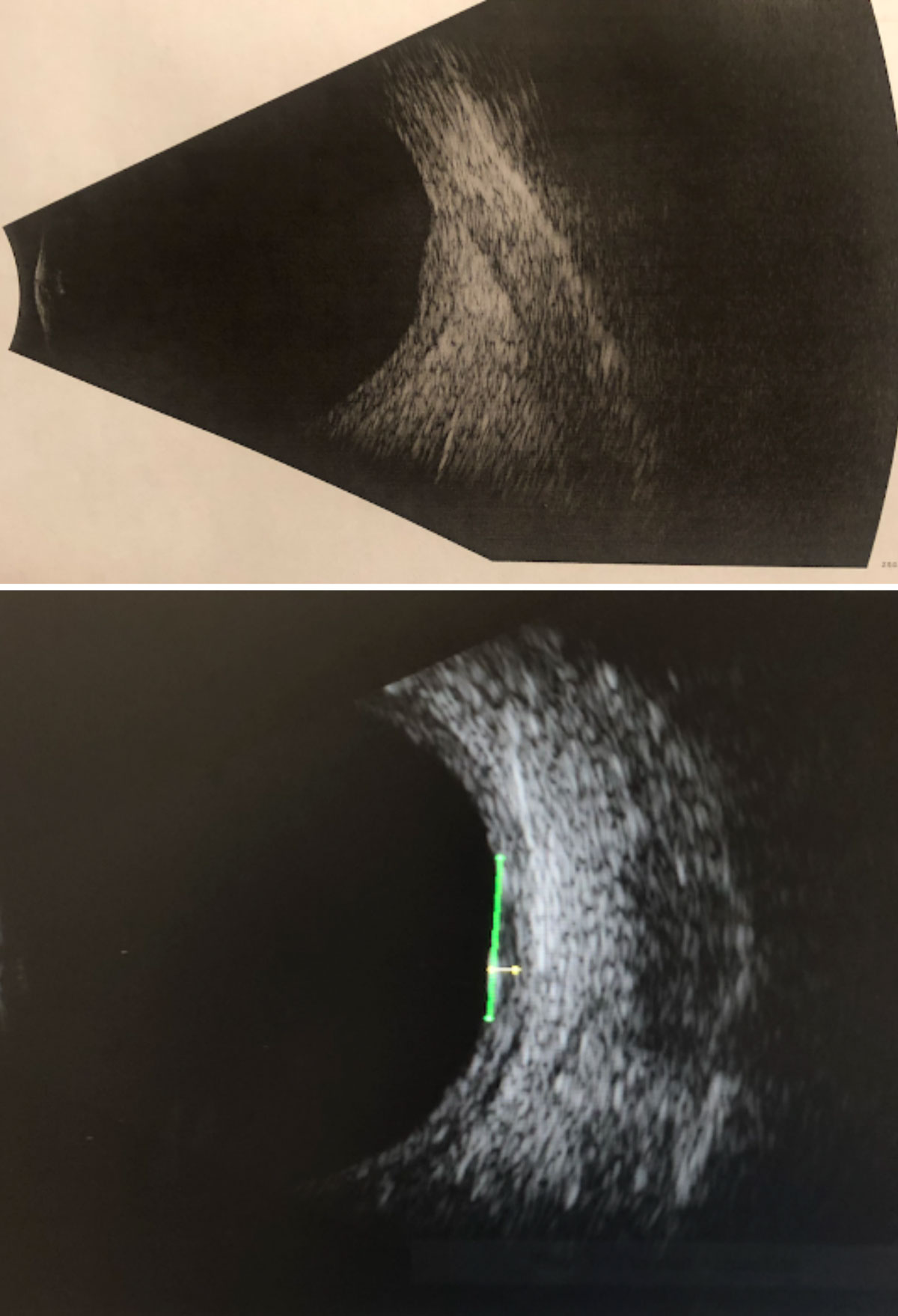

The patient returned two days later for an initial evaluation with a retinal oncologist. His visual acuity, entrance testing and ocular health remained stable. B-scan ultrasonography revealed the following measurements: high internal reflectivity, transverse = 6.76mm; longitudinal = 5.92mm; horizontal (thickness) = 1.11mm (Figure 11). Retinal oncology confirmed and agreed with the initial findings and plans to follow up with the patient within two months for repeat testing.

|

| Fig. 7. A magnified fundus photo shows the dome-shaped lesion in the left eye temporal to the macula measuring 5- to 6-disc diameters. The presence of orange pigment spots, indistinct boarders, absence of drusen and halo can also be appreciated. Click image to enlarge. |

Follow up 2: With Retinal Oncologist

The patient returned for follow up two months later and denied any changes since the last visit. An updated OCT and B-scan through the lesion in left eye revealed stable findings. A thorough discussion of different treatments, including risks and benefits, were explained to the patient. Ultimately, the decision for plaque brachytherapy was recommended, but the patient requested more time before initiating treatment. The patient was scheduled for follow up in another two months for repeat testing and further discussion of the treatment options.

Follow up 3: With Retinal Oncologist

The patient returned for follow up almost three months later and again denied any changes since the last visit. His visual acuity, entrance testing and ocular health remained stable. Plaque brachytherapy was again discussed with the patient, but he declined the recommended treatment against medical advice. Retinal oncology planned to continue two-month interval follow ups with the patient to monitor for changes over time.

Discussion

The differential diagnoses in this case included intra-ocular melanoma (primary and secondary), choroidal nevus and congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE). Choroidal nevi are common, benign melanocytic lesions that are typically flat and slate gray in color, whereas congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium are typically flat with well-defined scalloped edges and central depigmented lacunae.9 In this case, the growth and change in size over time with the presence of thickness, subretinal fluid, irregular borders and orange pigment spots led to the diagnosis of an intra-ocular choroidal melanoma.

|

| Fig. 8. The macula OCT shows underlying subretinal fluid with elevation within the lesion. Click image to enlarge. |

Melanomas of the choroid, ciliary body and iris of the eye are known as uveal melanomas with nearly 80% affecting the choroid.7,10 The incidence is six cases per one million with about 7,000 new cases diagnosed per year worldwide.7,11 Primary intraocular melanomas are the most common malignant tumor in adults.7 Up to 4% of patients with nevus of ota will go on to develop a uveal melanoma in the affected eye.6 Women tend to be diagnosed more than men, although research does not support any gender predilection.7,10 Recent research shows that there may be a hereditary component with presence of the BAP1 (GEP class 2) gene having the poorest survival rate.11

|

| Fig. 9. Multicolor images help visualize separate layers of the retina by using different wavelengths. Click images to enlarge. |

Unfortunately, about 50% of all choroidal melanomas will develop metastatic disease.16 The size of the tumor is the single most important predictor of metastasis.17 The five-year mortality rate for a small uveal melanoma (less than 3mm in thickness) was 13%, medium sized (3mm to 10mm) is 23% and large (more than 10mm) is 43%.18

The thickness of the presumed choroidal melanoma of our patient is 1.11mm, which is considered a small choroidal melanoma; however, growth over a short period of time increases the risk of metastasis by eight times.12 Additionally, the presence of subretinal fluid, orange pigment spots, absence of drusen, absence of halo on B scan and progression from previous examinations significantly increases the patient’s risk of metastasis and mortality.

|

| Fig. 10. With multicolor images, the orange pigment spots (far left) as well as the irregular borders (far left and far right) on the dome-shaped lesion in the left eye become more apparent. Blue wavelengths isolate the inner retinal structures (middle left); green wavelengths isolate the intraretinal structures (middle right); and the infrared wavelengths visualize the outer retinal structures, choroid and retinal pigment epithelium (far right).8 Click image to enlarge. |

A systemic workup should be performed prior to any ocular treatment to rule out metastasis (Chattopadhyay, 2017).10 Staging workup to rule out metastases of a choroidal, or uveal, melanoma should include a minimum of complete blood count, liver function tests and diagnostic imaging using at least one of following: computed tomography (CT) of chest and abdomen, whole body positron emission-CT (PET-CT) or liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and chest CT.19

This patient chose to have his medical care provided outside of our hospital and an update on any systemic oncology workup is unknown at this time.

|

| Fig. 11. B-scan ultrasonography through the suspicious lesion in the left eye without measurements (top) and with measurements (bottom): High internal reflectivity; transverse = 6.76mm; longitudinal = 5.92mm; horizontal (thickness) = 1.11mm. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment Options

There are numerous treatments for ocular tumors, including laser, radiation and surgical therapies.7 For this patient, the ocular oncologist recommended plaque brachytherapy, which is a type of radiation therapy. Plaque brachytherapy is the most common globe-sparing therapy (Reichstein, 2018).20 The procedure generally includes sewing an individualized plaque made of gold with embedded radioactive iodine-125 seeds to the outside of the eye behind the tumor. Gold plaques block the soft radiation emanating from the iodine seeds.21 The ophthalmic oncologist then delivers a highly concentrated dose of radiation to the tumor.22 The plaque typically remains in place for one to seven days.23

Potential radiation side effects are highly variable and depend on many parameters, including tumor size and location, but may also be related to procedure planning and surgical techniques.24 The most common side effects include strabismus, cataracts, glaucoma, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, radiation retinopathy, radiation maculopathy and scleral necrosis.25 Anterior segment pathology has been reported in 4% to 23% of treated patients.24

This is an extremely rare case of a Caucasian patient with nevus of ota that progressed into a primary choroidal melanoma. Any ocular melanoma is a serious malignancy with a poor prognosis when metastasis occurs.26 When evaluating a patient with a suspected choroidal melanoma, documentation of growth and imaging, including fundus photos, OCT and B scan, are critical. Management of these patients warrants a prompt consult to a retinal ophthalmologist with clinical expertise in ocular tumors and oncology, and radiation oncology when appropriate.10,26

Drs. Krabill and To are optometrists at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital Eye Clinic in Tampa, FL.

1. Mohan RP, Verma S, Singh AK, et al. ‘Nevi of Ota: the unusual birthmarks’: a case review. BMJ Case Reports. 2013;2013: bcr2013008648. 2. Chan H, Kono T. (2007, June 21). Nevus of ota: clinical aspects and management. Skinmed. 2003;2(2):89-96. 3. Turnbull JA, Assaf C, Zouboulis C, Tebbe B. Bilatera naevus of Ota: a rare manifestation in a Caucasian. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18(3):353-5. 4. Magarasevic L, Abazi Z. Unilateral open-angle glaucoma associated with the ipsilateral nevus of ota. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2013;2013:924937. 5. Yang JL, Luo G, Tuyana S, et al. Analysis of 28 Chinese cases of bilateral nevus of ota and therapeutic results with the Q-switched Alexandrite laser. Derm Surg. 2016;42(2):242-8. 6. Sharan SG, Grigg JR, Billson FA. (2005). Bilateral naevus of ota with choroidal melanoma and diffuse retinal pigmentation in a dark skinned person. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(11):1529. 7. Singh P, Singh A. Choroidal melanoma. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2012;5(1):3-9. 8. Heidelberg Engineering Academy. (2018). Spectralis MultiColor Image Interpretation. https://business-lounge.heidelbergengineering.com/gb/en/products/spectralis/multicolor-module/tutorials. Accessed August 17, 2020. 9. Weidmayer S. Choroidal melanoma is a life sentence. Rev Optom. 2012;149(1):48-55. 10. Chattopadhyay CK, Kim DW, Gombos DS, et al. (2017). Uveal melanoma: from diagnosis to treatment and the science in between. Cancer. 2016;122(15):2299-312. 11. Helgadottir H, Höiom V. (2016). The genetics of uveal melanoma: current insights. Appl Clin Genet. 2016;9:147-55. 12. Nayman TB, Bostan C, Logan P, Burnier Jr MN. Uveal melanoma risk factors: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Curr Eye Res. 2017;42(8):1085-93. 13. Cheung AS, Scott IU, Murray TG, et al. Distinguishing a choroidal nevus from a choroidal melanoma. EyeNet. 2012 February:39-40. 14. Shields CL, Furuta M, Berman EL, et al. Choroidal nevus transformation into melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(8):981-87. 15. Shields CL, Cater J, Shields JA, et al. Combination of clinical factors predictive of growth of small choroidal melanocytic tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(3):360-400. 16. Damato B. Ocular treatment of choroidal melanoma in relation to the prevention of metastatic death - A personal view. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;66:187-99. 17. Kaliki S, Shields CL. Uveal melanoma: relatively rare but deadly cancer. Eye (Lond). 2017;31(2):241-257. 18. Grossniklaus HE. (2019, April). Understanding uveal melanoma metastasis to the liver: the Zimmerman effect and the Zimmerman hypothesis. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(4):483-87. 19. Weis E, Salopek TG, McKinnon JG, et al. (2016, February 23). Management of uveal melanoma: a consensus-based provincial clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(1):57-64. 20. Reichstein DK, Karan K. Plaque brachytherapy for posterior uveal melanoma in 2018: improved techniques and expanded indications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29(3):191-98. 21. Shah PK, Narendran V, Selvaraj U, et al. Episcleral plaque brachytherapy using ‘BARC I-125 Ocu-Prosta seeds’ in the treatment of intraocular tumors: A single-institution experience in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60(4):289-95. 22. Diener-West ME, Earle JD, Fine SL. The COMS Randomized Trial of Iodine 125 Brachytherapy for Choroidal Melanoma, III: Initial Mortality Findings COMS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(7):969-82. 23. Tagliaferri LP, Pagliara MM, Boldrini L, et al. INTERACTS (INTErventional Radiotherapy ACtive Teaching School) guidelines for quality assurance in choroidal melanoma interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) procedures. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2017;9(3):287-95. 24. Wen JC, Oliver CS, McCannel TA. Ocular complications following I-125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma. Eye. 2009;23(6):1254-68. 25. Peddada KV, Sangani R, Menon H, Verma V. Complications and adverse events of plaque brachytherapy for ocular melanoma. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2019;11(4):392-97. 26. Patel DR, Patel BC. Cancer, Ocular Melanoma. StatPearls: Treasure Island (FL); 2020. |