Many clinicians panic when confronted with a patient who is pregnant or nursing and needs treatment for an ocular condition. In my experience, unfounded fears, a historically confusing and simplistic FDA classification system and limited data on ophthalmic medications often cause eye care practitioners to withhold treatment or undertreat this patient population.

| |

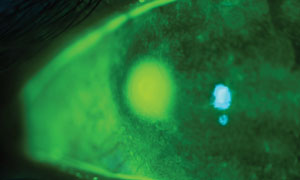

| Tobramycin, with a historical FDA category B rating, is commonly used for pregnant patients diagnosed with bacterial keratitis. Photo: Ami R. Halvorson, OD. |

However, compiled data suggest the majority of severe birth defects are due not to drug side effects, but to genetic or chromosomal abnormalities.1,2 Additionally, most teratogenic birth defects are due to alcohol, illicit drug consumption or infective teratogens and not the use of over-the-counter (OTC) and FDA-approved medications.1,2 Finally, the risk of birth defects resulting from topically-applied medications is extremely low, suggesting that, although prescribing for the pregnant patient requires an increased level of caution, especially in gestational weeks two through 10, there are a variety of relatively safe options available for most ocular disease conditions.3

This article discusses the use of ophthalmic medications during pregnancy and lactation, and what practitioners should take into consideration when treating patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Considerations for Breastfeeding Patients

When prescribing for breastfeeding patients, clinicians must weigh the benefits of medication use for the mother against the potential risks to the infant, such as the repercussions of not breastfeeding the infant or exposing the infant to the medications. A drug considered safe for patients who are pregnant may not be safe for patients who are nursing.4 Clinicians can limit the breastfed infant’s exposure to medication by prescribing medications to the mother with poor oral absorption, educating the mother to avoid breastfeeding during times of peak maternal serum drug concentration and prescribing topical therapy when possible.

Mothers with medically fragile infants may need different dosing to minimize drug accumulation and toxicity in the infant.4

| |

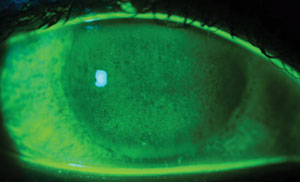

| Patients who are pregnant and have dry eye will often notice a worsening of their symptoms. Photo: Ami R. Halvorson, OD. |

Dilating

Another concern is the use of dilating drops during the course of pregnancy and breastfeeding. The consensus is occasional dilation is acceptable, but that repeated use of these agents should be avoided if possible.5-7 Due to an increased half-life, clinicians should avoid the use of longer duration parasympatholytics such as atropine, scopolamine and homatropine. The shorter acting agents such as tropicamide or cyclopentolate are considered safer for use in pregnancy and lactation. The ophthalmic sympathomimetic phenylephrine should be avoided unless dilation with tropicamide only is inadequate and a dilated retinal examination is necessary for the treatment or evaluation of a current ocular condition.5-7

Oral Antibiotics

Pregnant and nursing women develop skin and soft tissue infections just like any other patient. Expect at some point in your career to examine a pregnant or nursing patient with a hordeolum, dacryocystitis, preseptal cellulitis or similar presentation. We should not undertreat this patient by avoiding oral antibiotic therapies with the historic category B FDA rating such as Augmentin (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, GlaxoSmithKline), erythromycin, azithromycin and amoxicillin, as they are used routinely during pregnancy and are approved by obstetricians for infections from gestation through breastfeeding.6-9

All of these choices provide the broad-spectrum coverage we generally seek in treating lid and ocular adnexa infections. However, just as in the pediatric population, it is prudent to avoid tetracycline and fluoroquinolone derivatives when treating pregnant and lactating patients, as they offer increased risks to the developing fetus or infant.10,11 Tetracycline and its derivatives—including doxycycline and minocycline—have been known to cause discoloration of teeth and maternal liver toxicity.12 Fluoroquinolone derivatives such as oral ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin or levofloxacin have been associated with lab animal fetal cartilage-forming defects, and their use in pregnant patients is controversial despite data to suggest relative safety.13

| |

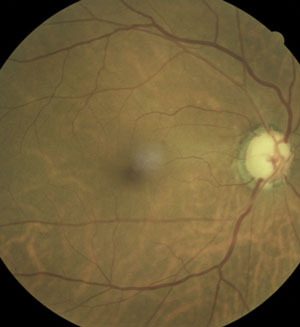

| Because oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are contraindicated during pregnancy, consider using labetalol as a topical glaucoma treatment. Photo: Ami R. Halvorson, OD. |

Topical Treatments

For topical antibiotics, such as those needed to treat bacterial keratitis, tobramycin has the historical FDA category B rating and has been used extensively in pregnancy as a topical ophthalmic antibiotic.14 The use of topical fluoroquinolones during pregnancy has not been well studied; however, because of their undisputed efficacy in the treatment of corneal ulcers, these medications may be necessary if the benefits outweigh the potential risk to the developing fetus.

Fortified topical cephalosporin antibiotics, such as cefazolin and ceftazidime, have an excellent safety profile and can be made into ophthalmic preparations by a compounding pharmacist for severe bacterial keratitis if tobramycin isn’t acceptable, the fluoroquinolones are of concern, or neither provide adequate coverage. For less severe infections, such as bacterial conjunctivitis or prophylaxis against infection, erythromycin, polymixin B and topical azithromycin are other safe options.15-17

Pain Management

There are situations when a patient who is pregnant may need pain control for an ocular issue. Corneal abrasions or lid lacerations are certainly reasons for considering oral pain management. Aspirin and other oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are a concern during pregnancy, and acetaminophen alone, although generally acceptable for short-term use during pregnancy, may not give the level of relief necessary.18

Although prolonged and heavy use of opioid agents has been shown to affect the fetus, opioids such as acetaminophen with codeine are routinely used by obstetricians for short-term relief from painful conditions during pregnancy.19

During breastfeeding, the synthetic codeine derivative hydrocodone is preferred, as genetic differences exist between patients, which can cause more conversion of codeine to morphine, resulting in opioid overdose in a breastfed infant. Therefore, hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen may be the preferred agent.19

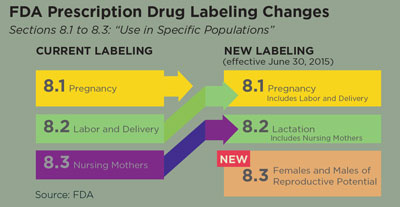

| An Update on the FDA’s Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling By Ami R. Halvorson, OD, and Erica Wiegandt, OD The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) passed the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Final Rule (PLLR) in December 2014. The new rule changed the labeling requirements for prescription medication as it pertains to women who are pregnant and breastfeeding, as well as men and women of reproductive age. The new guidelines are to assist health care providers in determining risk and benefit to an expecting or lactating mother when pharmaceutical therapy is needed. The new labeling system took effect on June 30, 2015. According to the FDA website, any new prescription drugs or biologic agents that are submitted for FDA approval after this date will be labeled with the new labeling system. Any drugs or agents that are subject to the Physician Labeling Rule—drugs that were FDA approved after June 30, 2001—will be gradually phased into the system within the next three to five years. Manufacturers are required to remove the lettering category within the next three years for any product approved before June 30, 2001. Clinicians will continue to see prescription drugs labeled with the older lettering system until they are updated. Currently, no topical ophthalmic medications are consistent with the new labeling rule. Manufacturers of the prescription drugs are responsible for relabeling their medications as data for pregnant and breastfeeding women become available. The manufacturers are not subject to conduct new studies to evaluate risks to pregnant or lactating women, but they are required to evaluate up-to-date medical literature and revise their labeling accordingly.1 Over the counter (OTC) medications are not subject to the PLLR and will not be relabeled.

• Pregnancy. The Pregnancy subsection, termed ‘subsection 8.1’, no longer includes the pregnancy categories (A, B, C, D, X, N) but instead includes a narrated section on risk summary, clinical considerations and data for a given drug. In addition to these sections, a pregnancy exposure registry, when available, is also required—something that was only recommended in the past. • Lactation. The Lactation subsection, termed ‘subsection 8.2’, contains pertinent information about a medication as it applies to a nursing mother, such as the amount of prescription medication in the breast milk and possible effects on the child. This subsection also has the risk summary, clinical considerations and data subheadings. • Patients of Reproductive Potential. The Females and Males of Reproductive Potential subsection, termed ‘subsection 8.3’, is a brand new category that provides information on a given medication and the need for pregnancy testing, contraception recommendations and information on infertility. The location for this information on a particular drug has not been consistently categorized before. New Labeling Benefits The new labeling system was created because it was felt that the older lettering system, implemented in 1979, was overly simplistic and perhaps did not convey the potential drug risks to the prescribing care provider. The former lettering system was thought to be misinterpreted as a grading system that was often confused by practitioners. Hopefully, the new narrated system will better convey risks involved in prescribing. A definite advantage to the new PLLR is that it takes the gestational age of the pregnancy into consideration. With the lettering categories, it was assumed that a medication was equally safe or equally dangerous throughout the pregnancy. The PLLR addresses timing of exposure during specific trimesters.2 The PLLR also addresses the widespread lack of data on many medications, since pregnant women are often excluded from clinical trials due to the ethics of the unknown. Much of the teratogenic data obtained is through observational or epidemiological studies. A 2011 study reviewed the safety of 172 drugs that were FDA approved from 2000 to 2010 and found that 168 (97.7%) of the drugs scrutinized lacked enough data to determine the teratogenic effects of the medications during a pregnancy.3 In efforts to collect more information, there are many pregnancy registries that collect data on already approved medications that are often used during pregnancy. They compare the data to the same population not taking the medication to look for trends. As of December 2014, the FDA has a labeling rule that requires drug manufacturers to include pregnancy registry contact information on the medication label. This should help physicians and pregnant patients easily participate in the registry, which can lead to improved data collection for medications.4 There are over six million pregnancies in the United States each year, and it is estimated that a woman takes three to five medications during her pregnancy.5 Because many comorbidities during pregnancy require treatment, optometrists are bound to be in a position to prescribe for a pregnant or breastfeeding patient. The FDA’s new labeling system should help optometrists have a clearer understanding of the safety profiles and risks involved with the medications they prescribe. As with virtually all practitioners, optometrists have to make informed decisions based on the risks vs. benefits to a patient in need of diagnostic or therapeutic medications. The new labeling system will provide the prescriber more organized data on the potential risks and benefits to the mother, the fetus, the breastfeeding child and to men and women of reproductive ages. Of course, consulting with a woman’s obstetrician is always a potential option when considering prescribing medications during pregnancy. Protecting a pregnant or breastfeeding patient from unintentional adverse effects of diagnostic and therapeutic medications is undoubtedly every practitioner’s intent and the new labeling system should make this easier than before. Dr. Halvorson is a graduate of Pacific University College of Optometry and is currently employed at Pacific Cataract and Laser Institute in Portland, OR. Dr. Wiegandt is a recent graduate of Pacific University College of Optometry and is currently employed at Family Eye Care in Grand Forks, ND. 1. Traynor K. Changes Coming to Pregnancy Labeling. Pharmacy News. 2015 February. Accessed November 25, 2015. www.ashp.org/menu/news/pharmacynews/newsarticle.aspx?id=4159. 2. Schatz M, Chambers C, Mitchell A. Preg/Lac Talk Back: Your FDA Pregnancy Labeling Questions Answered. Clinical Drug Information. 2015 October. Accessed November 25, 2015. www.wolterskluwercdi.com/blog/preglac-talk-back-your-fda-pregnancy-labeling-questions-answered/. 3. Adam M, Polifka J, Friedman J. Evolving knowledge of the teratogenicity of medications in human pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011 Aug 15;157C(3):175-82. 4. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Registries Help Inform Medication Use in Pregnancy. 2014 December 17. Accessed November 28, 2015. www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm223320.htm. 5. Kweder S. Helping patients and health care professionals better understand the risks and benefits of medications for pregnant and breastfeeding women. 2014 December 3. Accessed November 25, 2015. http://blogs.fda.gov/fdavoice/index.php/2014/12/page/2/. |

Systemic Antiviral Meds

Ocular herpes simplex can present in patients who are pregnant as well, and recurrences may be more common during pregnancy given the stressed systemic state and decreased immunity. Periocular herpetic lesions, corneal dendritic ulcerations or herpes-induced conjunctivitis can prompt the need for antiviral therapy.

Because oral antivirals such as acyclovir have been used by obstetricians for the prevention of pregnancy-induced genital herpes outbreaks and transmission of the virus to the fetus, these medications have been found to be well-tolerated in pregnant women and can be used when necessary for ocular herpetic conditions.20 In fact, oral antivirals such as acyclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir have the historic FDA pregnancy category B rating, while topical antivirals such as Viroptic (trifluridine, Pfizer) and Zirgan (ganciclovir, Bausch + Lomb) have the historic FDA category C rating. This is likely because they have been less frequently prescribed and observed than their oral counterparts. Oral acyclovir has also been approved by the American Academy of Pediatrics for lactating women.21

Managing Ocular Surface Disease

Dry eye patients often experience worsening of their ocular surface disease during pregnancy. Restasis (topical ophthalmic cyclosporine, Allergan), is typically used as a primary treatment; however, although not found in the bloodstream after topical administration during the FDA trials, it is historically designated as category C. Therefore, avoid cyclosporine when possible and instead recommend an increase in frequency of nonpreserved artificial tears, gels and ointments, as well as punctal plugs for the pregnant patient with dry eye.

Associated ocular allergies can be treated with Lastacaft (alcaftadine 0.25%, Allergan) safely. Other similar allergy drops that have a comparable mechanism of action to Lastacaft, such as Pataday (olopatadine 0.2%, Alcon) and Pazeo (olopatadine hydrochloride 0.7%, Alcon), have the historic FDA category C rating and are not recommended for use in patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Such a disparity between medications highlights the need for the FDA’s updated labeling system (see “An Update on the FDA’s Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling”).

As many ocular conditions have associated inflammation, eye care practitioners often desire to prescribe a topical steroid. The use of a topical corticosteroid is indicated for conditions such as contact lens-induced inflammation, iritis and sterile infiltrative keratitis. Although many practitioners are concerned about the use of topical steroids in pregnancy given their side effect profile, ophthalmic steroids are approved by obstetricians for ocular inflammation because of the low amounts of systemic absorption.22 Check with the patient’s physician, however, for oral steroid treatment.

Glaucoma During Pregnancy

To treat glaucoma during pregnancy, oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), such as Diamox (acetazolamide, Lederle), are contraindicated.23,24 Although adverse effects on the fetus are unproven, it may be prudent to avoid topical CAIs such as Trusopt (dorzolamide, Merck) and Azopt (brinzolamide, Alcon) and prostaglandins such as Xalatan (latanoprost, Pfizer), Lumigan (bimatoprost, Allergan) and Travatan (travoprost, Alcon). Although it is unlikely prostaglandins would cause harm as a once- daily ocular drop, their use is often avoided due to their important role in the induction of labor.25

Although topical glaucoma treatments in pregnancy have been poorly studied, labetalol is commonly used orally during pregnancy for the treatment of hypertension.25 If used, topical beta-blockers should be avoided in the first trimester. Alphagan (brimonidine, Allergan) is the only topical ocular hypotensive agent with the historically more preferable FDA category B pregnancy rating. Brimonidine should be avoided, however, in lactation, as its use has been associated with inducing apnea and central nervous system depression in the breastfeeding infant.26

Consider surgical options such as trabeculectomy or selective laser trabeculoplasty if these medications are not controlling the patient’s IOP, or if medications must be avoided entirely.

While some treatments are safe and effective during pregnancy and lactation, for some patients the best treatment may be no treatment. Many practitioners and their patients choose close observation without therapy because IOP is naturally and progressively lower during each trimester of pregnancy due to an increase in circulating prostaglandins and hormonal changes.

Dr. Autry received her pharmacy degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She practiced in critical care before returning for her optometry degree at the University of Houston. Following graduation, she performed a residency in ocular disease at the Eye Center of Texas ophthalmology center, where she is a partner today.

1. Christianson A, Howson CP, Modell B. March of Dimes Global report on birth defects. Executive Summary. White Plains, NY:2006. www.marchofdimes.org/materials/global-report-on-birth-defects-the-hidden-toll-of-dying-and-disabled-children-executive-summary.pdf.2. CDC. Birth defects. September 21, 2015. www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/facts.html.

3.UK Teratology Information Service. Use of Eyedrops in Pregnancy. 2011 April. http://bmec.swbh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/EYE-DROPS-IN-PREGNANCY.pdf.

4. Spencer JP, Gonzalez III LS, Barnhart DJ. Medications in the breast-feeding Mother. Am Fam Physician. 2001 Jul;64(1):119-127.

5. Bhatia J, Sadiq MN, Chaudhary TA, Bhatia A. Eye changes and risk of ocular medications during pregnancy and their management. Pak J Ophthalmol. 2007;23(1).

6. Gil Ruiz MR, Ortega Usobiaga J, Gil Ruiz MT, Cortés Valdés C. Ocular pharmacology during gestation and breastfeeding. www.oftalmo.com/.

7. Lynch CM, Herold AH, Sinnott JT, Holt DA. Use of antibiotics during pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 1991 Apr;43(4):1365-8.

8. Miller KE. Diagnosis and treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Apr;73(8):1411-6.

9. Nahum GG, Uhl K, Kennedy DL. Antibiotic use in pregnancy and lactation: what is and is not known about teratogenic and toxic risks. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 May;107(5):1120-38.

10. Berman B, Perez OA, Zell D. Update on rosacea and anti-inflammatory-dose doxycycline. Drugs Today. 2007 Jan;43(1):27-34.

11. Leibovitz E. The use of fluoroquinolones in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006 Feb;18(1):64-70.

12. Rothman K, Pochi P. Use of oral and topical agents for acne in pregnancy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1988;19(3):431-442.

13. Loebstein R, Addis A, Ho E, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to fluoroquinolones: a multicenter prospective controlled study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998 Jun;42(6):1336-9.

14. Bausch + Lomb. Tobramycin ophthalmic solution package insert. Bridgewater, NJ, August 2015.

15. Pfizer. Erythromycin package insert. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, November 2014.

16. X-Gen Pharmaceuticals. Polymyxin B package insert. Grayslake, IL, May 2015.

17. Merck. Topical azithromycin package insert. Woodstock, IL, July 2012.

18. Antonucci R, Zaffanello M, Puxeddu E, et al. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in pregnancy: impact on the fetus and newborn. Curr Drug Metab. 2012 May;13(4):474-90.

19. Nezvalová-Henriksen K, Spigset O, Norden H. Effects of codeine on pregnancy outcome: results from a large population-based cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 Dec;67(12):1253-61.

20. Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir in the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. JAMA. 2010;304(8):859-66.

21. Sheffield JS, Fish DN, Hollier LM, et al. Acyclovir concentrations in human breast milk after valciclovir administration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:100-2.

22. Chung C, Kwok A, Chung K. Use of ophthalmic medications during pregnancy. Hong Kong Med J. 2004;10(3):191-195.

23. Brauner S, Chen T, Hutchinson B, et al. The course of glaucoma during pregnancy: a retrospective case series. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006 Aug;124(8):1089-94.

24. Vaideanu D, Fraser S. Glaucoma management in pregnancy: a questionnaire survey. Eye. 2007;21(3):341-3.

25. Pickering T. Treating Glaucoma During Pregnancy. Glaucoma Today. 2009 March. http://glaucomatoday.com/2009/03/GT0309_03.php/.

26. Trad MJ. Some ophthalmic drugs not safe for use in lactating or pregnant women. Helio. Primary Care Optometry News. 2008 September.