|

A 70-year-old Caucasian male presented on a Monday morning, reporting that he had lost his vision in his right eye the Friday prior and ended up in the emergency room with a blood pressure of 65/42. He had undergone a CT, MRI, carotid Doppler and EKG, all of which were normal. He was released and told his vision would likely recover. He had no such luck over the weekend.

The patient said he has had a significant headache and scalp tenderness on the right side of his head for approximately one week. He had lost about 30 pounds recently and has had a fever of unknown etiology. Medical history was positive for controlled diabetes (HbA1c was 6.4), high cholesterol and a recent bout of shingles on the left side. He is currently finishing his Valtrex (valacyclovir, GlaxoSmithKline) and a low-dose oral steroid regimen.

The patient’s entrance acuities were hand motion OD and 20/30 OS. His anterior segment was within normal limits OU, as were his intraocular pressures. The labs we ordered included CBC, ESR and CRP. The ESR, using the Wintrobe method, was 38mm/hr, with a reference range of 0mm/hr to 9mm/hr. The CRP was 11.78, with a reference range of 0 to 0.9.

Diagnosis

Based on these findings, our first diagnosis was anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION).

The patient’s inflammatory markers were atypical with regard to a varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection-associated neuritis, though VZV may have a potential association with giant cell arteritis (GCA), our second diagnosis.

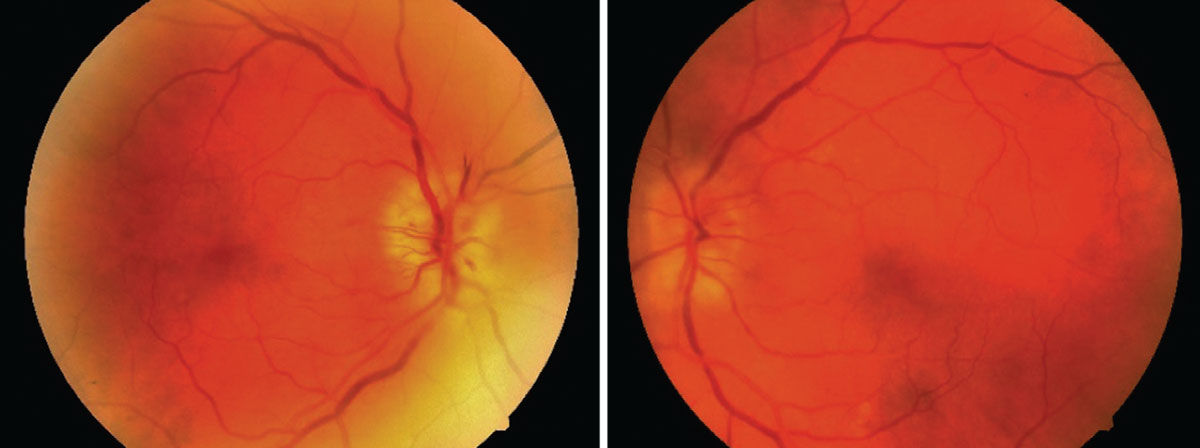

|

| Here are the findings from the patient’s dilated fundus examination, OD on the left. Click image to enlarge. |

GCA, named because of the giant cells found on vessel histology slides, is a granulomatous inflammation of the large- and medium-sized arteries, particularly in the external carotid branches, vertebral artery, subclavian artery, axillary artery and thoracic aorta. GCA is the most common form of vasculitis that occurs in adults.1

GCA and temporal arteritis have not always been synonymous. Traditionally, GCA was separated into Takayasu arteritis and temporal arteritis (Horton’s disease). However, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) has since provided an accepted convention to categorize vasculitides so that now, GCA is the accepted nomenclature for what is oftentimes still referred to as temporal arteritis.

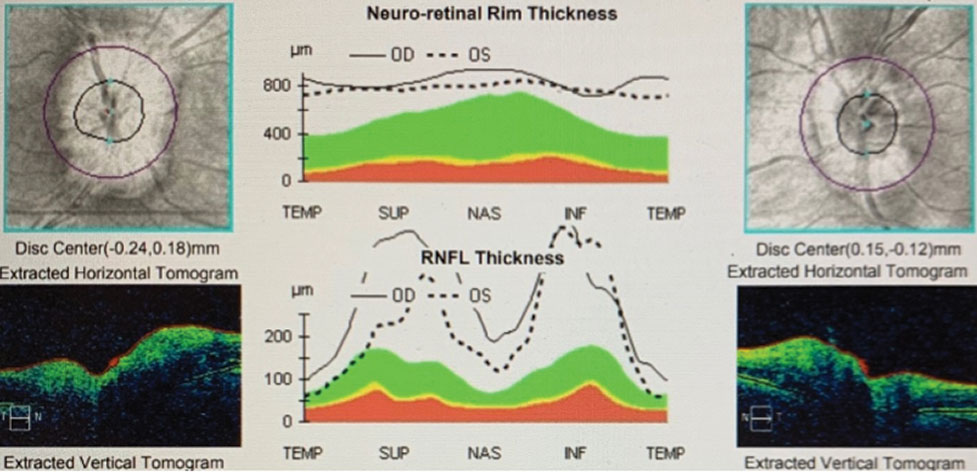

|

| OCT shows the relative swelling of the optic nerves, OD>OS. Click image to enlarge. |

Takayasu arteritis and GCA both affect more women than men.2 While GCA has an average onset age of 72 years and is almost always found in patients over the age of 50, Takayasu arteritis is typically a disease seen in younger Asian women.2

GCA often presents with the following symptoms: headache, fever, scalp tenderness, dry cough, weight loss, depression, mononeuritis multiplex (which may manifest as numbness and/or tingling), glossitis, polymyalgia rheumatica and/or jaw claudication. Abrupt onset of a significant headache is the most frequent symptom of GCA and is seen in approximately 75% of cases.3

Vision loss due to AION is an early manifestation of GCA and can be a presenting symptom. AION occurs in 20% to 50% of people with untreated GCA.4 Up to 10% of patients lose their vision in the second eye despite treatment.5 This can happen within one week. Other possible ocular sequelae include cilioretinal artery occlusion, central retinal artery occlusion and transient ischemic attacks.

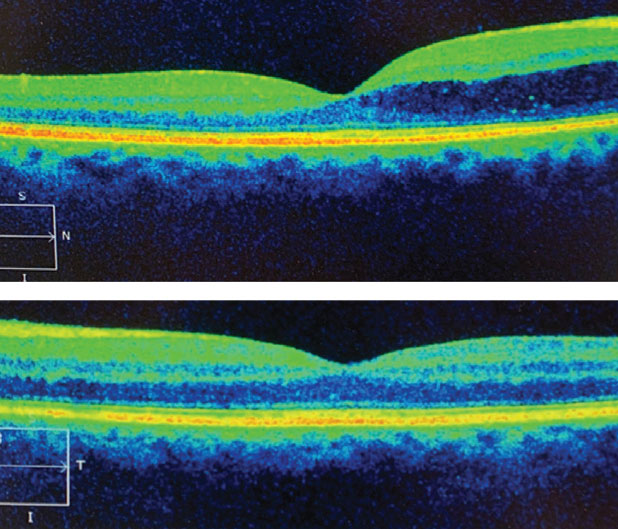

|

| There was fluid egression into the macula OD, top, not OS. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment

We diagnosed our patient with AION secondary to GCA based on age and associated signs and symptoms. In these cases, it is imperative to begin systemic steroidal treatment as soon as possible, so long as the patient can take systemic steroids. Because our patient was already suffering from more advanced effects of suspected GCA, starting prednisone superseded the need for a confirmatory temporal artery biopsy.

The general starting dose for prednisone in GCA is between 60mg/day and 80mg/day. Symptoms usually begin to rapidly resolve within one to three days. GCA is known to require a very long, slow taper. It is common for patients to remain on steroids for more than a year. For steroid regimens of this dose and duration, the doctor must educate the patient on possible side effects, such as blood glucose increase, gastric reflux (proton pump inhibitors are prescribed), weight gain, mood change and bone density reduction (biophosphonates are almost always prescribed concurrently with the steroids). The patient should have their electrolytes and liver enzymes monitored during treatment and be followed with imaging studies, as aortic aneurysms and/or dissections are possible with GCA. GCA patients are now routinely prescribed tocilizumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, as a steroid-sparing agent to increase steroid-free remission times.6

Our patient’s ESR returned to near-normal within a month, and his CRP returned to an acceptable value within a couple of weeks. Unfortunately, his diabetes worsened secondary to steroid treatment and required more extensive management, with his blood glucose levels rising to 263 and his HbA1c, to 11.3. His visual acuity remained at hand motion OD and improved to 20/20 OS. His florid optic nerve head edema OD and mild optic nerve head edema OS both resolved. Internal medicine took over management of his GCA-associated anemia.

This patient’s case demonstrates one of the various ways GCA may present, as well as the effects that delays in diagnosis and treatment can have on any comorbidities, including vision. As we recognize the appropriate signs and symptoms, we can taper our laboratory and imaging studies to a tentative GCA diagnosis and get our patients on the road to recovery.

Vasculitis ClassificationsAccording to the CHCC, the known vasculitides are categorized as follows:

|

Dr. Duncan is the founding coordinator of the Optometric Surgical Procedures program at the Southern College of Optometry.

Dr. Baldridge practices at Insight Eyecare in Tulsa, OK. She graduated from the Southern College of Optometry and completed an ocular disease residency at the Oklahoma Medical Eye Group.

1. Giant Cell Arteritis. Johns Hopkins. www.hopkinsvasculitis.org/types-vasculitis/giant-cell-arteritis/#:~:text=Giant%20cell%20arteritis%20(GCA)%20is,in%20one%20or%20both%20eyes. Accessed August 4, 2020. 2. Landry GJ. Giant Cell Arteritis. Society for Vascular Surgery. www.vascular.org/patient-resources/vascular-conditions/giant-cell-arteritis. Accessed August 4, 2020. 3. Warrington KJ, Matteson EL. Management guidelines and outcome measures in giant cell arteritis (GCA). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(6 Suppl 47):137-41. 4. Giant Cell Arteritis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/177.html. Accessed August 4, 2020. 5. Danesh-Meyer H, Savino PJ, Gamble GG. Poor prognosis of visual outcome after visual loss from giant cell arteritis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(6):1098-103. 6. Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of tocilizumab in giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:317-28. |