By the time optometrist Cory Steed was ready to enter the real world, the cost of his optometric education had put him $125,000 in the hole.

He graduated from Southern California College of Optometry (SCCO) in 2001, then undertook a one-year residency in Las Vegas. On the verge of entering the full-time workforce, he thought, Ive got the debt of a house, and I have nothing to show for it but my diploma.

But Dr. Steed didnt rack up those bills unnecessarily. He wasnt one of those kids who inflated his loans by buying a new BMW, going on tropical vacations or eating at four-star restaurants.

Just the opposite. He lived frugally. He shared an apartment with three other students. He walked to campus. He had no cell phone. No cable TV. He worked a part-time job during his first few years of school.

He says that he found himself in such a large amount of debt due to three simple factors: His family couldnt contribute much to his education; its pricey to live in Southern California; and the cost of a private-school professional education is just expensive.

The good news is that Dr. Steed didnt let his debt make decisions for him. Nor did it force him to put his life on hold. He and his wife have since bought a house in Las Vegas. He opened his own solo practice there a few months ago, and his wife runs the business side. Their first child will have been born by the time you read this article.

This article looks at the increasing problem of student debt, what can be done about it, and whether it drives career choices. (Next month: How new grads have opened their own practices cold.)

Drastic Deepening

Is student debt really a problem? And, if so, how big a problem is it? Consider these points:

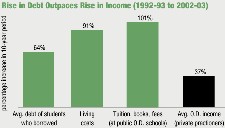

Debt has risen dramatically. The average indebtedness among optometry students who borrowed has increased by 64% in the past decade, from $64,089 in the 1992-93 school year to $105,074 in 2002-03, according to data from the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO).

Tuition costs have risen. Costs of tuition, books, fees and instruments have doubled for some students. For example, fourth-year in-state students in public optometry schools spent an average $6,072 on these costs in 1992-93 and more than twice that, or $12,213, in 2002-03. Fourth-year in-state students in private optometry schools spent $13,703 in 1992-93 and $19,421 in 2002-03, a rise of 42%. Meanwhile, fewer government grants are available to help cover these expenses, ASCO reports.

Living costs have risen. Living costs, as compiled by ASCO, have nearly doubled, from an average of $8,702 in 1992-93 to $16,654 in 2002-03. (The 2003 data reflects a 12-month school year.)

Income hasnt risen as fast. The rising cost of tuition and living expenses would be counterbalanced if income had kept pace. Sadly, it hasnt. For example, income for private practitioners has risen by 37%, from $100,434 in 1993 to $137,142 in 2003, according to Review of Optometrys National Panel, Doctors of Optometry, income surveys.

One contributing reason for the rising levels of debt among todays students may be the increase in non-traditional students, says Tami Soto, director of financial aid at SCCO. Instead of just single students, we have older students, married students, married students with multiple children and single parents, she says. These students bring with them greater financial need than is provided by the standard budget.

Another factor for greater debt: Education simply costs more these days. The difference in tuition today vs. that of yesteryear is a different ballpark, says Paul Todd, assistant director of student affairs at the Ohio State University College of Optometry. Some of our O.D.s who have been practicing for 30 years talk about how they worked on the weekends to pay for their tuition, he says. Id love to see someone work on the weekends and pay for $4,500 [per quarter] in tuition.

He says that not scoffingly, but with complete sincerity. Mr. Todd, Ms. Soto and their colleagues in financial aid departments at the other optometry schools and colleges are concerned. Theyre worried about the growing costs of education and are working hard to help students keep from amassing the kind of debt that will impinge on their future careers.

Big Debt = Commercial O.D.?

This concern begs the question: Does debt affect career choice?

Its been a complaint among new grads for years: that heavy debt load forces many to take higher-paying but less satisfying jobs in commercial practice.

Thats an oversimplification and probably a misleading observation, says Larry McClure, Ph.D., assistant professor and associate dean for student financial affairs at Pennsylvania College of Optometry.

Several years ago, Dr. McClure carried out a study of more than a dozen variables that might affect a students eventual choice of practice.1 At 10 years after graduation, none of those factorsincluding student debtshowed a significant relationship to how a graduate would go on to practice as a doctor.

The study found a relationship only for those young O.D.s who were one year out of school. And student debt ranked no higher than fourth on that list. Dr. McClure acknowledges that this study is a few years old. Hes now in the process of updating it.

Similarly, Vito J. Cavallaro, director of financial aid and assistant vice president of student affairs at the State University of New York (SUNY) State College of Optometry, is working on a pilot study that would eventually produce a survey to determine how financial factors influence mode and location of practice.

Theres not a lot of data, especially in optometry, about students debt and what financial factors influence their debt, Mr. Cavallaro says. He says that he and other administrators at SUNY decided to do the study because of their concern about the rising cost of student debt. For example, the average amount of student debt at SUNY is about $95,000 to $98,000, he says. But that average includes perhaps a third of students with debt of about $150,000 or more.

While he has no data yet, Mr. Cavallaro says that many write-in responses to the survey complain that debt among new grads affects their lifestyle choices, if not their professional ones. They thought theyd be more financially secure in the profession, he says.

Lightening the Debt Load

To make debt more manageable, many schools have implemented a variety of strategies. Most of these serve to educate ill-informed new students about financial pitfalls and the slippery slope of debt.

At SCCO, students have practice management classes in three out of the four years. These courses cover topics of budgeting and financial planning, Ms. Soto says.

Illinois College of Optometry also includes debt management in its curriculum. For the past three years, ICO has had an elective course specifically on debt management, says Mark Colip, O.D., vice president for student affairs. Students are hungry for information on financial planning, he says.

Another measure ICO took was to implement a tuition freeze between 1998 and 2002. Dr. Colip says the freeze was necessary to keep the tuition in the same range as other private optometry schools, as well as to do everything the school could to control the escalating cost of education. Indeed, ICO is still one of the higher-priced schools. Currently, four years of tuition costs $104,000. Plus, the average student typically borrows $44,000 for living expenses over four years, carries $14,358 of undergraduate debt, and incurs $10,237 in accrued interest. That equals a total average debt of more than $170,000 at graduation. That number actually dropped a bit in 2004, Dr. Colip says, due in part to the debt management course.

Here are some other ways schools are trying to help students lighten the debt load:

Counseling. Financial aid administrators at some schools start talking about debt with prospective students right in the application interview. That kind of dialogue continues throughout the students education, as the financial aid office keeps students well apprised of financing options and their current and future debt loads.

For instance, we make the student determine what amounts they want from the subsidized and unsubsidized Stafford loans, instead of just packaging in the maximum amounts, Ms. Soto says. This adds a step to the process and makes them have to think about what they really need.

At OSU, Mr. Todd gives each student a financial aid spreadsheet that lists all that the student has borrowed. He includes what he calls scare tactics into it; these are reminders of such things as their total indebtedness, or what they had predicted their indebtedness to be in that introductory interview. Mr. Todd sends out these statements right before students are required to update their financial aid packages for the following year.

Minimize living expenses. While students have no control over their tuition costs, they can have some control over their living expenses. These are seemingly marginal expenses, PCOs Dr. McClure says, but the less a student has to borrow to pay for these expenses, the less he or she will have to pay back with interest in the future.

One example Dr. McClure always uses: bottled water. Buy one bottle of water a day, and thats $7 a week. Thats $364 down the drain a year. On water! The same principal applies to buying a cup of Starbucks coffee each day. Likewise, he asks, do you need cable TV? Do you really need a car? Can you split the cost of an apartment with a roommate?

We estimate our students will spend about $1,400 or $1,500 a month on living expenses, Dr. McClure says. Then I ask them, do you think you can get by on $1,200 or $1,300? If so, you just saved $2,400 a year. Over four years, thats almost $10,000 you saved. And probably nothing changed, except that you got a roommate, and that you didnt buy bottled water or buy coffee at Starbucks.

Curb credit card spending. Credit card companies specifically target undergraduate and graduate school students. They set up tables on the quad and give away T-shirts and Frisbees to get students to apply, says ICOs Dr. Colip. Every bulletin board is covered with credit card ads. Its no wonder that average credit card debt among graduate students rose 59% between 1998 and 2003, from $4,925 to $7,831, according to the student loan provider Nellie Mae.

To that end, ICO has banned credit card companies from advertising on campus, and the school tries to help wean students off excessive credit card spending.

Increase work-study. Despite a greater curriculum load on students, some schools have been able to increase the pay and availability of work-study jobs. ICO expanded its work-study program, issuing $1 million in work-study funds this year. This keeps students on campus and makes a serious impact on borrowing, Dr. Colip says.

Consolidate loans. Perhaps the biggest factor in helping to manage debt in the past few years is loan consolidation. Loan rates are the lowest in almost 40 years. (As of July 1, the Stafford rate dropped to 2.77%.) Students can borrow more without spending more, says Dr. McClure. He calculates that a student who graduates with a debt load of $125,000 could consolidate his loans over a 30-year term, and wind up paying a very manageable $515 a month.

Students really want to consolidate now because these rates are not going to remain where theyre at, says Kevin Smith, an administrator for Student Assistance Foundation, which handles AOA Advantage, the one-year-old consolidation program through the American Optometric Association. The current consolidation rate for new grads is now 2.875%. Compare that with a high rate period between 1997-1999 when regular loan rates skyrocketed to 7.75%.

A Great Investment

Even with the current amount of debt, an O.D. degree is still a great investment, Dr. McClure says. From the get-go you have more money in your pocket than you would have had if you had chosen to go into the workforce with your bachelors degree, he says. On average, workers with professional degrees earned higher annual salaries than those with masters, bachelors or even doctorate degrees, reports the U.S. Census. (See What Is Your Degree Worth? above.)

Another good sign that student debt isnt disastrous: zero loan default rate. From AOA Advantage to individual school loan programs, optometrists have a zero (or near zero) default rate. It speaks to the fact that income-wise, they are doing very well, says Dr. Colip, and that were turning out responsible graduates.

Still, if debt rises again in the forthcoming decade as it did in the past decade, the picture may not be so rosy. Dr. Colip, however, predicts that skyrocketing tuition costs will eventually plateau.

Somethings got to change, says the young Dr. Steed. For one, he says, more insurance panels should credential O.D.s to allow them to bill as they should, which would permit optometrists income to keep pace with the rising cost of education.

1. McClure L. Student indebtedness: The challenge of financing an optometric education. Optometric Education 2000;25(2):45-53.