|

Throughout this series, we have explored how to effectively comanage patients with ophthalmologists and other medical specialists. While this is a critical component of optometric practice, in many circumstances another OD can be the preferred partner. Intraprofessional collaboration can offer you three vital things that, frankly, may be lacking in some other comanagement relationships: access, trust and respect.

“I believe that optometry as a profession would be much stronger if we collectively referred patients to one another more, and not just to ophthalmology,” says Brian Chou, OD, of San Diego, who concentrates on helping patients with keratoconus and other corneal disorders who need specialty contact lens fits. “It is a privilege to help other optometrists in the community,” he says. “Their patient’s experience in my practice reflects on the referring doctor. For this reason, I feel accountable to the referring doctor and will do my best to help their patient.”

Practicing at the highest level not only means cultivating your expertise and knowledge as a primary eye care provider, but also recognizing when a referral is the right choice.

“We all take an oath to provide our patients with the best care possible, and the only way to do so is to recognize when one of our colleagues is better equipped to handle a patient’s specific needs,” notes Joshua L. Robinson, OD, director of the low vision rehabilitation service at the Vanderbilt Eye Institute. “Whether by virtue of skill-set, experience, equipment, time, location or resources, sometimes a fellow OD is able to better care for a particular patient. It is thus important to recognize and make appropriate referrals in a timely manner.”

Comanagement ConnectionsCheck out other articles in this series: The Many Layers of Cornea Comanagement Be a Retina Referral Rock Star Keep Glaucoma Care Close to Home |

This final article in our six-part comanagement series will delve into intraprofessional optometric referrals. It will highlight how to successfully collaborate with a fellow OD. This includes building relationships, addressing challenges and identifying when it’s the right time to tap into another OD’s expertise.

OD/OD Collaboration

There are a variety of reasons why an OD may consider employing the skills of another optometrist. Whether you don’t feel comfortable, don’t have the necessary equipment or prefer not to manage a certain aspect of a patient’s care, it is important to know you have an ally when you refer to a colleague.

Let’s first consider some of the more clear-cut paths to intraprofessional collaboration—instances where the OD on the receiving end is a specialist in a niche aspect of care much like the ophthalmology subspecialists profiled in other installments of this series.

Vision therapy. An estimated one in four children have undiagnosed vision problems that interfere with learning and lead to academic and/or behavioral problems, according to Megan Lott, OD, FCOVD, a developmental optometrist at a specialty clinic in Hattiesburg, MS. There is a widespread need for vision therapy, and ODs are in the perfect position to identify these patients.

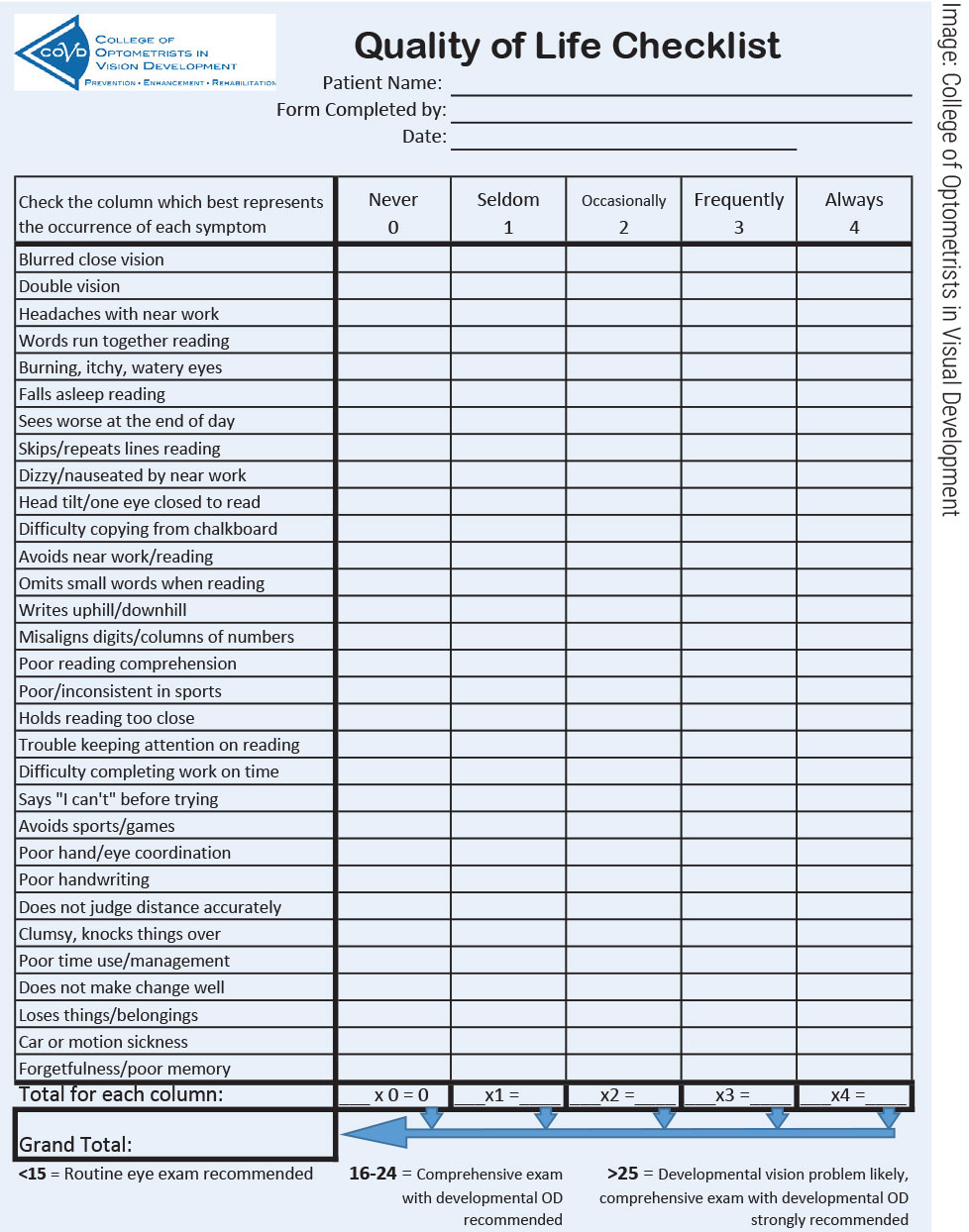

While all ODs have some training in the concepts and practices of vision therapy, not all have chosen to specialize in this area of care. Therefore, it is important to know when to refer to another optometrist. This includes taking a thorough case history and evaluating visual efficiency. Dr. Lott recommends adding a quality of life checklist from the College of Optometrists in Visual Development (COVD) to your intake forms.

“It is a brief, 19-item checklist that can help determine if a patient might have a functional vision problem,” she says. “If there is evidence of an issue, the OD can choose to dig deeper or refer to someone who will. This is a tool that is easy to integrate into practice and a good way to determine if further examination or a referral is needed.” You can find a copy in the online version of this article at www.reviewofoptometry.com or on COVD’s website at www.covd.org.

|

|

This form can help you identify patients with functional vision problems so you can direct them to specialty care. Click image to enlarge. |

It is also important to think about what you want for your patient. “For example, if you’re sending to an ophthalmologist, your patient with an eye turn is probably going to undergo surgery,” Dr. Lott notes. “If you refer them to me, the intervention will be much more conservative with a focus on trying to fix the root of the problem.” Surgery should not be your first line of treatment for strabismus, she stresses, and patching should not be your first line of treatment for amblyopia. “There are so many better ways to treat this condition.”

So, Dr. Lott notes, you must ask yourself how you will define treatment success. “Is it simply cosmetic enhancement? Is this a child who is struggling in school? What intervention will provide the best outcome?” Referring to an optometrist who specializes in vision therapy not only helps your patient, but also means you are working with someone who is more likely to align with your treatment modality, notes Dr. Lott.

Low vision. You’d be hard-pressed to find a discipline more in line with the core values of optometry than low vision, an area of care characterized by precise visual assessment, expertise in optics and empathy for patients—all optometric hallmarks.

This is an area where many of your patients could derive significant benefit from working with an OD whose specialty is low vision. Especially as optometry continues to take on the role of primary eyecare provider, practitioners will see increasingly more patients with uncorrected acuity deficits caused by AMD, diabetic eye disease and glaucoma, to name a few. Leaving them with a visual deficit simply because their eye health has stabilized would be a disservice.

The question is: when do you refer? A common approach is to set a visual acuity threshold, but that’s not the only consideration. While thresholds like visual acuity/visual field/contrast sensitivity can be helpful, the most important consideration is whether a patient has functional needs that cannot be addressed by medicine/surgery or the spectacle and contact lenses you’re able to prescribe, according to Dr. Robinson. “If the answer is ‘yes,’ they should be referred.”

Listen to your patient and their needs. Ask them questions, e.g., “Do you have trouble doing what you want to do because of your vision?” This could include reading the mail, watching television, signing your name and reading screens, to name a few.

Whether you are the referring OD or the low vision specialist, you must not forget about the person behind the diagnosis. “While it may be easy to fixate on the medical management of a condition, which is of course incredibly important on its own, we can’t lose track of the person who feels the impact of that condition,” says Dr. Robinson. “Equipping that individual to function despite their vision impairment is the core purpose of low vision rehabilitation.”

If an OD does not have the tools to provide comprehensive low vision rehabilitation, it is crucial for the well-being of their patient to refer them to a provider who does. “Stocking simple handheld magnifiers and a few digital magnification tools can be helpful, but a disservice is done to our patients when they aren’t exposed to a comprehensive program and end up with any of their needs left unmet,” urges Dr. Robinson. “Partner with services that have the time and financial flexibility to navigate the challenges of low vision rehabilitation while you comanage the patient’s medical eye care needs,” he emphasizes.

|

|

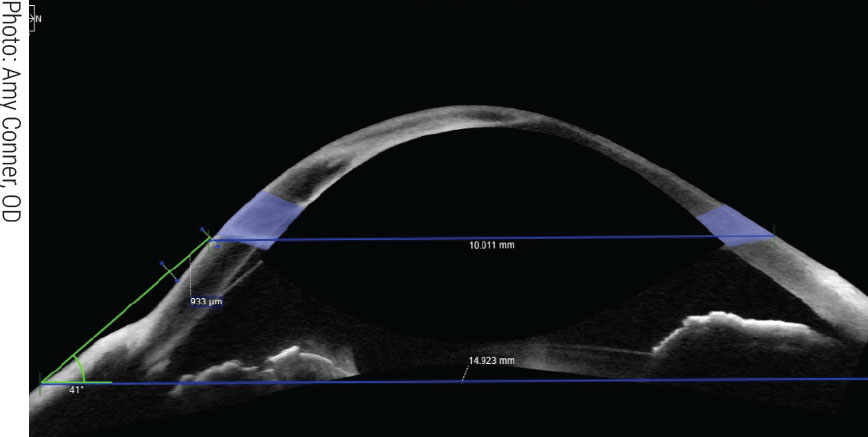

ODs who offer specialty lens fits typically have access to advanced equipment like anterior segment OCT, allowing for more precise results. Click image to enlarge. |

Specialty lenses. The field of specialty contact lenses, especially scleral lenses, has seen significant growth in recent years, offering many patients new avenues of treatment. However, fitting these lenses and other custom designs requires extensive expertise and a significant time commitment.

Not every OD wants to handle this aspect of care, and that’s okay—there are optometrists who are passionate about this niche and are ready and willing to comanage alongside the primary eye care provider.

“I am here to provide support and be a resource to the ODs in my area,” says John Gelles, OD, of Teaneck, NJ, whose clinical work is dedicated solely to specialty lenses and complex corneal disease. “I will manage all aspects of the fitting process and the ongoing care of the disease being managed with the lens and the lens itself while ensuring the patient continues being cared for by their primary provider.”

The most important aspect of specialty lenses is the management of the condition prompting a need for them, such as severe ocular surface disease, keratoconus or other corneal conditions. How involved Dr. Gelles will be depends, in part, on the skills and comfort of the referring OD. “I am not here to step on anyone’s toes,” he says. However, it is vital to make sure the patient receives the care they need. “The majority of patients I see with severe ocular surface disease who need PROSE treatment or therapeutic lenses are extremely complex, requiring a management team which could include oncology, neurology, rheumatology, ophthalmology and so on,” he continues. “It can be a lot to manage.”

Dr. Gelles will have a conversation with the referring OD to determine what the comanagement relationship will look like and set roles and expectations. “It’s important to avoid a ‘too many cooks’ situation because it can degrade the confidence a patient has in both providers if they aren’t on the same page. The relationship works best when roles are clearly defined, and each stays committed to them.”

Key questions he asks aid in guiding the relationship by understanding the referring doctor’s comfort level and preparedness such as, “What is your comfort level in managing the disease?” and “Do you have the diagnostic equipment needed to follow this disease at a high level?”

These questions help the providers understand each other’s capabilities and limitations. If a referring doctor feels equipped to handle the disease follow-up, Dr. Gelles will step aside once the lens is finalized and the acute condition is resolved or stabilized. If not, he will manage follow-up for the condition requiring the contact lens, while the referring OD will continue to manage the patient’s primary vision needs and all other aspects of their overall ocular health.

DIVIDE AND CONQUEROptometry doesn’t have formal subspecialties, so there’s a sense that ODs need to be able to manage anything that walks in the door—a concept that is increasingly untenable, especially as scope of practice continues to expand. “I take exception to the suggestion that an OD should handle as much as possible in their office before referring out,” says Dr. Chou, likening this to trying to be a jack of all trades and master of none. Because his practice is specifically attuned to serving keratoconus patients and addressing their needs at a higher level of service, Dr. Chou has on hand topography, anterior segment OCT, hybrid and scleral diagnostic sets, impression-based scleral lens capability, various scleral lens removal tools, genetic testing for keratoconus and patient literature on keratoconus—not to mention countless hours of clinic time with this patient population. “Sure, a practitioner who does not routinely care for keratoconus patients can manage them without outside referral, yet it may not be their best use of time and it may not be in the patient’s best interests,” he says. This is not to dissuade practitioners from continually expand their skillset and reflexively refer out all the time, he emphasizes. “Rather, each OD needs to practice within their own capability. If I have a patient who would benefit from low vision services, I will not hold onto that patient. Even though I could provide the service, it would underserve the patient’s best interests. Likewise, I will also refer out patients who would benefit from vision therapy.” Dr. Rafieetary concurs. “If the OD is both professionally and financially satisfied in practicing the mode they have chosen to practice, I don’t think they are lacking in any way.” As long as they stay abreast of changes in the healthcare environment, keep up-to-date with available technology and treatment options, are able to detect vision- and life-threatening conditions and make appropriate and timely referrals, “they are playing their part admirably and appropriately,” he suggests. |

Ocular disease. Beyond optometry-specific services focused on visual needs, there are countless opportunities to turn to another OD for medical eye care assistance rather than assuming such patients must see an ophthalmologist.

“At times our primary care colleagues have an instinct to refer their patients only to the OMDs instead of their OD colleagues in the same practice,” says Mohammad Rafieetary, OD, of a large retina practice in Memphis. However, he points out that “if the OMDs trust us to practice side by side with them, our community-based colleagues should feel confident extending us the same courtesy.”

In fact, optometrists in a multidisciplinary setting are often the ideal liaison for other ODs in the community, proving them access and attention that may be harder to obtain from the ophthalmologists in the practice.

“I understand everyone has the prerogative to refer to whom they feel comfortable with based on clinical skills, personal relationship and so on,” says Dr. Rafieetary, “but I would suggest primary care ODs communicate with the referral center OD to understand their roles in the practice and use these optometric colleagues as their resource and referral point.” Doing so frees the practice’s ophthalmologists to provide the care they are uniquely trained for, most notably surgical services, and gives the referring doc a more engaged partner to work with.

|

|

While all optometrists should be cognizant of low vision interventions that can help their patients, some cases will require a referral to a specialist for optimal results. Click image to enlarge. |

“The ODs in our community have learned we will take their pathology cases on the spot, which is comforting to them for emergent cases that need help immediately,” says Houston’s Jill Autry, OD, RPh, who works at a large multidisciplinary practice. “All the ODs in town have our cell phone numbers, and we answer their calls and texts during the day, night, weekends and while on vacation. They know we have trained alongside ophthalmology for years and trust our care. They know we will turn to the ophthalmologists in our practice if we need them.”

Connection and Communication

As with any comanagement arrangement, success depends on strong relationships as well as effective communication. This means both optometrists must take the time to not only connect with one another but also develop an understanding of each other’s approach to patient care.

“Communication and expectations are probably the most important components of effective comanagement,” emphasizes Dr. Robinson. “I rely on the referring OD or MD to continue to monitor and effectively manage a patient’s eye condition to help prevent further loss of vision.”

At the same time, “The referring doctor relies on me to address the patient’s functional needs created by that eye condition,” he continues. “Establishing a realistic understanding of this collaborative setup and communicating effectively once the relationship is established are both incredibly important.”

A comprehensive referral letter is key. It should provide detailed clinical information, including diagnoses and treatment history as well as ancillary testing results such as visual fields. It is also important for the referring OD to clearly outline what they need from the optometrist they are referring to.

An open line of communication ensures everyone is on the same page. “While a patient may be under my care for a certain period of time, I am not their primary provider,” explains Dr. Lott. “Just as the referring OD shares information with me, I will provide a thorough report on what I have done and why so that they remain included in care.”

“We call or send the referring doctor a message regarding the exam that same day,” Dr. Autry says, “and we discuss the case with them so they also learn about something they may not see as often as we do.”

Patient communication is also vitally important, especially since you are referring to a fellow OD and there can be confusion regarding the role of each provider. Helping your patients navigate this requires a thorough explanation of the process as well as clearly and repeatedly outlining the care each optometrist will provide.

“From the very beginning of the referral process, I make sure that the patient understands what I do and the part I will play in their care,” says Dr. Gelles. “I emphasize to the patient that I don’t provide any primary eye care and that they will return to their OD for that aspect.”

The doctor receiving the referral should work to strengthen the patient’s bond with their primary OD. “I feel it is important to reinforce to the patient how they were fortunate to see the referring doctor,” says Dr. Chou. “It takes humility for a doctor to admit that what is best for the patient may be beyond their scope of care and comfort level.” The referring doctors deserve praise and recognition, he emphasizes. “When a keratoconus patient experiences an exceptional outcome and thanks me for it, I let the patient know that the credit really goes to the referring doctor.”

Patients who require a referral will often need frequent follow-up with the specialist OD in addition to primary eye care. As a result, the patient may be under the misconception that their routine care is being managed.

“We have a responsibility to make sure the patient understands the importance of maintaining comprehensive care, including routine exams,” emphasizes Dr. Gelles. For example, progressive corneal diseases, such as keratoconus, involve ongoing monitoring, and patients may assume that this qualifies as their routine eye exam. “I make sure they know that they need to return to their primary OD for routine care and that is something I reinforce during every visit.”

Addressing Challenges

While collaborating with a fellow optometric professional—instead of an ophthalmologist or another medical specialist—can be easier in many ways, navigating the intraprofessional dynamic can prove challenging for different reasons.

Given you are referring to a doctor with comparable education and training, there can be concerns that this opens the door to losing a patient to a fellow OD. However, many optometrists who are passionate about a speciality want to focus most of their time on that area of care. They are there to complement the primary care services you already provide, not commandeer a patient and their overall vision management.

If anything, the fact that you share the same training and, oftentimes, a similar mindset, is invaluable, notes Dr. Lott. “There are plenty of patients for everyone,” she says. “And you can’t see them all. In fact, you cannot provide the very best care for your patients when you are trying to see everyone.”

Collaborating with ODs who have committed their time and energy to a subspecialty is in your best interest as well as your patient’s, she adds. “So, reach out. Ask for support. Work together for the betterment of our patients and the profession.”

In the case of vision therapy, ODs may not be referring patients as often as they could. “If you don’t look for it, you don’t see it,” says Dr. Lott. “These exams have to go beyond reading an eye chart and giving an Rx.”

Many times, the technicians will dilate the child as soon as they come in, she notes, which makes it difficult to conduct the necessary tests to determine if a patient could benefit from vision therapy.

“Optometry has become so focused on managing medical conditions that we have completely forgotten about functional visual disorders,” Dr. Lott states. “Many times, I see children who have already been diagnosed with a learning disorder such as ADD or dyslexia. And while medical conditions are a key component of our profession, we also have the power to change the entire trajectory of a child’s life who is failing school because of a vision-related learning problem.”

Dr. Lott also notes that ODs should not be hesitant to refer due to cost or distance. She acknowledges that insurance does not cover most vision therapy services and as a result some subspecialists, including herself, do not accept insurance. However, that should not be a reason to not refer.

“It’s not the job of the OD to decide if a parent can or cannot afford vision therapy,” she advises. “It is important to provide parents with all the information as well as their options and let the family make the decision.” Same goes for travel. “When their child is struggling, parents are willing to travel to get them the help they need.”

Concerning low vision rehabilitation referrals, Dr. Robinson notes that the biggest challenge is simply contending with the burgeoning demand. “Considering the continually growing number of visually impaired patients under our care, we are going to need more ODs committing themselves to low vision rehabilitation and students completing residency programs in this subspecialty area,” he says.

However, this is complicated by the reality that proper low vision care is time-consuming and very difficult to fit into a private practice model, according to Dr. Robinson, who explains that a comprehensive low vision rehab plan often involves a multidisciplinary team that can include occupational therapists, orientation and mobility specialists, vocational rehab teachers, teachers of the visually impaired, social workers and counselors.

“Putting together the most appropriate prescriptive devices with the best team to handle a patient’s very specific needs is time-intensive and requires a working knowledge of these referral resources,” Dr. Robinson emphasizes, while noting that these are some of the reasons why most comprehensive programs are found in the academic and nonprofit realms.

How can this change? “It likely won’t,” says Dr. Robinson, “until insurance reimbursement structures for low vision devices and services are altered to lessen the time and financial burdens that make it impractical for private practice ODs to take part.”

These challenges also underscore the importance of comanagement to ensure patients have access to these subspecialized providers.

Key Takeaways

|

For Patients and the Profession

There’s no shame in recognizing when you need outside support, advises Dr. Gelles, emphasizing that there are allies within the optometric profession who are more than willing to help care for your patients while allowing you to continue to take the lead.

It is also important to recognize the times when specialists refer out to you. “These complex patients still need primary eye care and often other optometric specialties, such as low vision or binocular vision,” notes Dr. Gelles. “I frequently refer to other ODs to manage these aspects, and I’m thrilled to refer the patient to someone super passionate about their specialty. I know the patient is getting the best care possible. Additionally, this allows me to stay focused on what I do best.”

“Recognizing when one’s resources cannot meet a patient’s needs and directing them to someone who is better equipped to handle this component of care is one of the many ways in which we uphold the optometric oath,” reiterates Dr. Robinson.

Comanagement is a cornerstone of healthcare and optometrists must feel comfortable working alongside one another for the greater good of their patients—and profession.