|

A 79-year-old man presented with a three-day history of headache and pain and tenderness on the right side of his head. He also had mild ocular discomfort OD and related that it felt similar to when he develops styes; he used artificial tears to no improvement. He denied weight loss, appetite loss and jaw claudication. He was otherwise feeling well.

Beware a Vesicular Rash

His uncorrected visual acuity was 20/40 OD and 20/30 OS, commensurate with his cataracts. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 13mm Hg OD and 10mm Hg OS. The remainder of his exam was normal. The only abnormality was a small, isolated vesicular lesion on his right lower eyelid. He did also have diffuse redness to his right forehead scalp, and he reported pain when his right temporal head was palpated.

Due to the head and scalp pain, two alternate diagnoses were considered; namely, herpes zoster dermatitis as the primary consideration and temporal arteritis as a secondary possibility. He was referred to obtain an erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, platelet count and hemoglobin level, as well as prescribed valacyclovir 1,000mg TID PO.

|

|

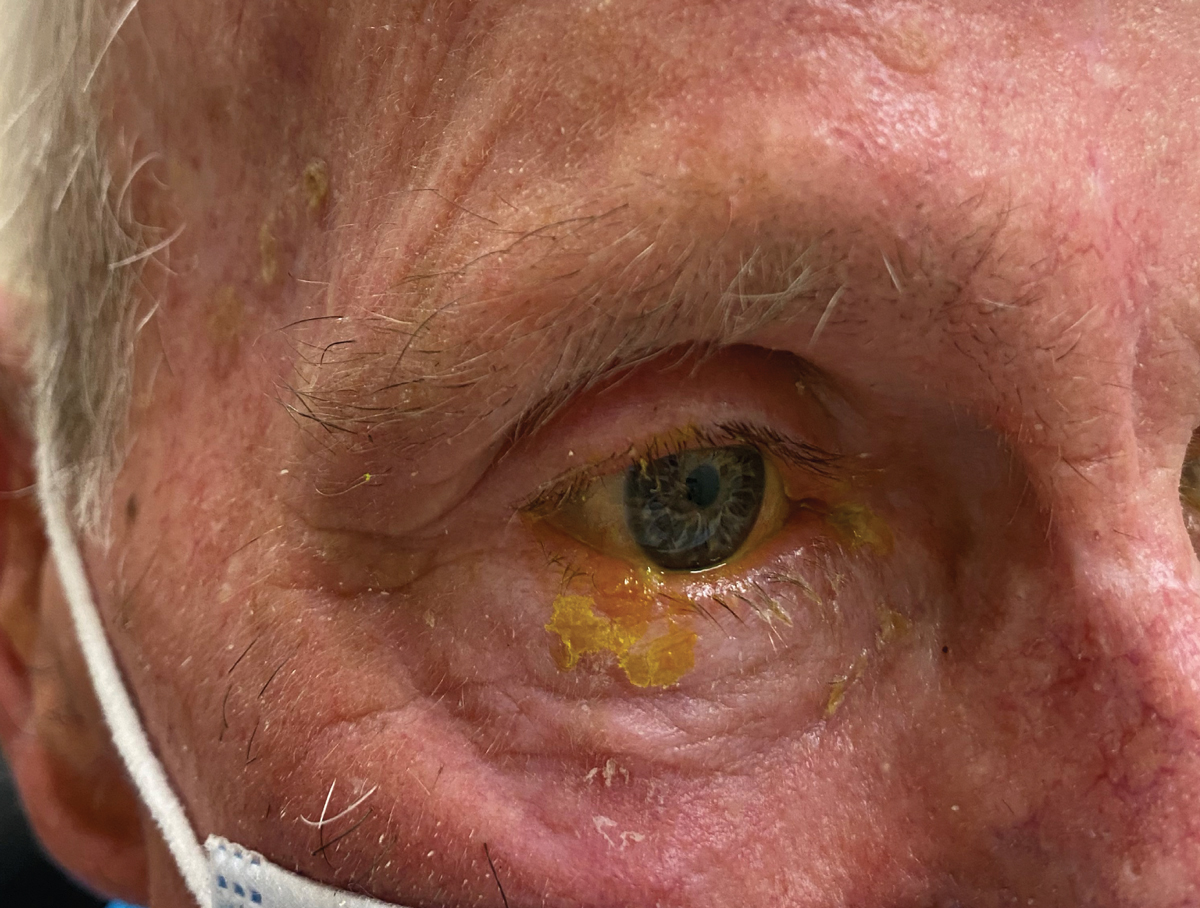

Initial presentation with mild eyelid involvement only. Click image to enlarge. |

He returned emergently the next day with rapidly worsening vesicular eruptions across the right side of his face and increased ocular discomfort. His acuity and IOP were unchanged, but he now had a blistering rash on his forehead extending to his scalp, upper and lower eyelid edema, several subepithelial infiltrates and keratic precipitates on his right cornea and a mild degree of flare in the anterior chamber.

His tests for temporal arteritis were normal. His diagnosis now clearly was herpes zoster dermatitis and ophthalmicus. He was maintained on valacyclovir and prescribed prednisolone acetate 1% QID OS. He was immediately referred to his primary care physician who then added a Medrol Dosepak (oral methylprednisone, Pfizer) and gabapentin 300mg TID PO to the regimen.

Burning Red

Herpes zoster rash can affect any dermatome on the body, but it most commonly resides in the facial and midthoracic-to-upper lumbar dermatomes.1,2 The rash appears as erythematous macules and papules, progressing into vesicles in approximately 12 to 24 hours. The rash then progresses into pustules at days three and four, with crusting at seven to 10 days. This rash is often accompanied by a regional lymphadenopathy.1-8 There is often a prodrome of fever, malaise, headache and dysesthesia over one to four days prior to developing of any visible cutaneous involvement.1

In fact, it may take 48 to 72 hours after the onset of pain for any sign of rash to emerge. At this stage, the diagnosis may be elusive and, in some instances, can be mistaken for giant cell arteritis. Burning pain classically precedes dermatologic involvement and can persist for several months after the rash resolves.1-12 Following resolution of the crusting pustules, about 9% of all patients suffer from extreme pain known as postherpetic neuralgia.1-8 Severe and possibly debilitating pain remains, despite the absence of active, visible skin lesions.1-12

The presentation of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) may vary from dermatologic involvement alone to ocular manifestations such as lid retraction, keratitis, scleritis, uveitis, glaucoma, retinitis (acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis), optic neuritis and panophthalmitis. When ophthalmic manifestations arise, the condition is termed HZO; it occurs in 7% of all zoster patients.2,4 Anecdotally, cases involving the eye have been observed to produce adnexal pain over months, without iritis, uveitis or vesicular breakout, making the chief complaint a mystery until the skin manifestations appear. The lesions of herpes zoster generally completely resolve within one to three weeks.6,7

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes chickenpox and herpes zoster represents a separate clinical condition caused by the same virus.1–12 The VZV is a member of the herpesvirus family. Varicella is spread by direct contact with active skin lesions or airborne via droplets and is highly contagious. The virus has an affinity for the upper respiratory tract and typically enters the human system through the conjunctiva and/or nasal or oral mucosa, producing the characteristic pox appearance.1–10 When the host’s immunity fails, the dormant virus leaves the confines of the dorsal root ganglion, where it lies dormant to produce chickenpox upon first infection or shingles (the zoster presentation) upon recurrence.1-12

Ninety percent of the population develops serological infection by adolescence, with nearly 100% of the population having some evidence of antibodies to the disease by age 60.1 Only 20% of patients suffer reactivation after initial infection.2 Any condition that decreases immune status, such as human immunodeficiency virus infection, chemotherapy, malignancy and long-term oral corticosteroid or other immunosuppressant use, increases the risk of herpes zoster activation. A second reactivation is even more rare and occurs mostly in immunosuppressed patients such as organ transplant recipients or those who suffer from AIDS or neoplasm.1

|

|

Profound vesicular eruption the next day despite being on oral antiviral medication. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment

Herpes zoster is managed using orally administered antiviral medications such as acyclovir (800mg PO five times a day), famciclovir (500mg PO TID) and valacyclovir (500mg to 1,000mg BID-TID for one week).1,10,12,13 The antiviral medications are most effective when initiated within 72 hours of the onset of the rash, especially for reducing the degree of post-herpetic neuralgia.12

Orally administered corticosteroids can reduce pain and potentially the onset of postherpetic neuralgia.10,12 Since the disease is self-limiting, most care is palliative, including the use of astringents, such as calamine lotion or aluminum acetate solution to minimize weeping and soothe the affected area, and topical antibiotic creams and ointments to prevent secondary infection. Patients with postherpetic neuralgia may require narcotics for pain control.12 Tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants in low dosages are potential options for unremitting pain.12 Capsaicin cream (based on the chemical in chili peppers that makes them hot), lidocaine patches and injectable nerve blocks can be used in the worst cases.12

Antiviral agents can play role in preventing varicella zoster disease in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.10 As with herpes zoster, acyclovir has been documented as effective in preventing disease reactivation, but the proper dose, duration and circumstance of its uses are controversial.10

Since VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity and cell-mediated immunity in general declines with age, it should be expected that the incidence of herpes zoster virus (HZV) increases with age. This may explain the increased incidence of HZV in immunocompromised individuals or those who are undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.7,8 Therefore, any patient younger than 50 who presents with signs of an acute zoster infection must be referred to rule out an immunocompromised state.

It is now well-accepted that herpes zoster should be combated prophylactically through vaccination. Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline), a recombinant zoster vaccine, reduces the incidence of herpes zoster by more than 90% and is preferred to the live, attenuated herpes zoster vaccine used previously. Shingrix is approved for adults 50 years and older. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends this vaccine for adults 60 years and older, except for certain immunosuppressed patients.14,15

For the patient reported here, upon his last follow-up eight weeks after his initial presentation, his ocular inflammation resolved on topical steroids and had been discontinued, as had the valacyclovir. He reported a great improvement in all findings, though he was still on gabapentin for postherpetic neuralgia.

Dr. Sowka is an attending optometric physician at Center for Sight in Sarasota, FL, where he focuses on glaucoma management and neuro-ophthalmic disease. He is a consultant and advisory board member for Carl Zeiss Meditec and Bausch Health.

1. Gurwood AS, Savochka J, Sirgany BJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Optometry. 2002;73(5):295-302. 2. McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(1):1-14. 3. Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ III, Kurland LT, et al. Population-based study of herpes zoster and its sequelae. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982; 61:310-6. 4. Karbassi M, Raizman MB, Schuman JS. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1992;36(6):395-10. 5. Cobo M, Foulks GN, Liesegang TJ, et al. Observations on the natural history of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6(1):195-9. 6. Burgoon CF, Burgoon JS, Baldridge GD. The natural history of herpes zoster. J Am Med Assoc.1957;164(3):265-9. 7. Arvin AM. Investigations of the pathogenesis of Varicella zoster virus infection in the SCIDhu mouse model. Herpes. 2006;13(3):75-80. 8. Carreño A, López-Herce J, Verdú A, et al. Varicella encephalopathy in immunocompetent children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(3):193-5. 9. Heininger U, Seward JF. Varicella. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1365-76. 10. Boeckh M. Prevention of VZV infection in immunosuppressed patients using antiviral agents. Herpes. 2006;13(3):60-5. 11. No author listed. Chickenpox, pregnancy, and the newborn. Drug Ther Bull. 2005;43(9):69-72. 12. Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D. Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(8):2437-48. 13. Martin JB. Viral encephalitis and prion diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al. eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, (14th ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998;1023-31. 14. Schmader K. Herpes Zoster. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):ITC19-31. 15. Saguil A, Kane S, Mercado M, Lauters R. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia: prevention and management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(10):656-63. |