Additionally, the use of perioperative medications, including antibiotics, corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), has improved surgical outcomes and lowered the risk of postoperative complications. Studies reveal that the rate of endophthalmitis associated with cataract surgery in 2016 was 0.023%, compared with 0.12% (more than five times greater) in 1994.1,2 Enhanced visual recuperation, amelioration of pain, diminution of corneal edema, mitigation of uveitis and attenuation of cystoid macular edema in the present era also may be directly linked to the use of postoperative corticosteroids and NSAIDs. Without question, these medications are critical to the safety and efficacy of cataract surgery. But can even these aspects of surgery be improved?

At present, our typical postoperative regimen for uncomplicated procedures consists of a fluoroquinolone antibiotic (TID to QID), a corticosteroid (typically QID) and an NSAID (either QD or QID, depending on the formulation) for 14 days after surgery; at this point, if recovery is acceptable, we discontinue the antibiotic and NSAID and begin tapering the corticosteroid for another two weeks. While such a routine may seem straightforward and easy for physicians who understand the role of these drops as well as their required frequencies, it can be monumentally difficult for patients to execute our orders with 100% compliance. The use of written instructions with pictures of the drops or descriptions of cap colors is helpful, but far from foolproof. The most frequent and time-consuming issue in our postoperative encounters is not managing surgical complications, but rather clarifying and re-educating patients on the appropriate use of their drops.

Drops, Out

One of the more recent and exciting innovations within the realm of cataract surgery has been the practice of “going dropless.” This concept involves an intracameral injection of antibiotic and anti-inflammatory medications at the conclusion of surgery (prior to wound closure) by use of a transzonular approach into the anterior vitreous space.3-7 Tri-Moxi (triamcinolone/moxifloxacin 15mg/1mg/mL, Imprimis Pharmaceuticals), Tri-Moxi-Vanc (triamcinolone/moxifloxacin/vancomycin 15mg/1mg/10mg/mL, Imprimis Pharmaceuticals) and Dex-Moxi (dexamethasone/moxifloxacin 1mg/5mg/mL, Imprimis Pharmaceuticals) became commercially available in mid-2014 and have gained acceptance by ophthalmologists ever since.The advantages of a dropless strategy are numerous. As the name implies, the use of intracameral medications at the time of surgery all but eliminates the necessity of instilling drops during the postoperative period. Patients are the primary beneficiaries of this modality, saving not only in terms of pharmacy visits but also the cost of multiple medications. Additionally, eliminating the need for self-instillation reduces the risk of potential injury or contamination from dropper bottles.8 For the doctor and staff, eliminating postoperative drops means less time is needed to educate and verify compliance with the prescribed regimen. Moreover, it means fewer potential complications from improper drug instillation.8 Perhaps most importantly, the dropless strategy virtually nullifies the dreaded pharmacy “call backs” regarding off-formulary medications or generic alternatives.

|

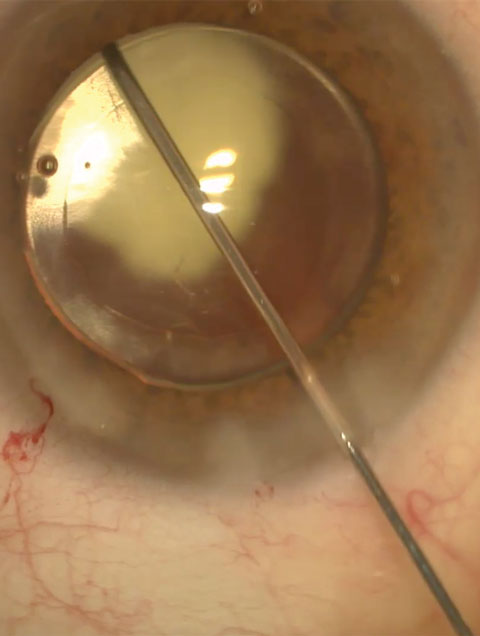

| Dropless surgeries such as this one are changing both how cataract extractions are performed and how ODs manage patients postoperatively. Photo: Lawrence Woodard, MD |

The Down Side

The dropless approach is not without its disadvantages, however. The additional cost of obtaining these drugs cannot legitimately be passed along to the patient, and hence the surgeon or surgical center must bear this expense. The intracameral preparations cost $20 to $25 per single-use vial. And while this may add up for a busy cataract surgeon, many are beginning to offer the dropless approach as a “value added” proposition to patients electing to have premium cataract procedures, such as laser-assisted surgery, toric or multifocal IOLs or accommodating IOLs.Another negative attribute of dropless surgery is the frequent issue of postoperative haze or floaters due to accumulation of drug particulate in the vitreous.3,6 While this effect is transient and generally lasts no more than a week, some surgeons fear that it negates the “wow factor” of dramatically increased vision in the immediate postoperative period. Newer approaches aim to inject the drug into the inferior vitreous to decrease obstruction of the visual axis. Additionally, having the patient maintain an elevated head position while sleeping ensures that the drug reservoir settles and remains inferiorly.

An array of potential adverse events is also associated with dropless cataract surgery, especially in cases of poorly executed technique. Recognized complications may include: zonular rupture with subsequent dislocation of the IOL; hyphema or isolated vitreous hemorrhage; iatrogenic retinal tears or detachments; iris prolapse; and ciliary body hemorrhage.4 But perhaps the most significant risk associated with dropless surgery is acute postoperative elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP). The association between IOP elevation and the use of intraocular corticosteroids is well-documented.9-12 Some consider it wise to avoid the dropless approach altogether in known steroid responders and proceed cautiously in those patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Patients must also realize that having dropless surgery is in no way a guarantee that eye drops can be completely avoided postoperatively. In cases of uncontrolled inflammation, associated IOP spike or other unanticipated events, adjunctive treatment with topical medications may still be necessary.

In the Literature

Although the dropless approach has been employed for years, only a small amount of information regarding its safety and efficacy exists in peer-reviewed literature. A retrospective analysis of 1,541 eyes undergoing the dropless procedure with compounded triamcinolone/moxifloxacin/vancomycin revealed no major intraoperative complications and no cases of postoperative endophthalmitis.4 Nearly 92% of cases required no supplemental medication after surgery. The rate of visually significant postoperative cystoid macular edema was just 2%, and the rate of clinically significant postoperative IOP elevation was <1%.4 These values are similar to those seen in patients undergoing traditional cataract surgery with the use of topical medications postoperatively.4 Another recently published report described a prospective, randomized, subject-masked contralateral eye study in which 25 individuals undergoing uncomplicated cataract surgery received a transzonular injection of triamcinolone/moxifloxacin/vancomycin at the time of surgery in one eye and topical, postoperative drop treatment in the fellow eye.5 No statistically significant difference was noted between the groups with regard to IOP elevation from baseline, macular thickness or corneal thickness after one month.5 The difference in reported pain (one day postoperatively) was also not statistically significant between groups.5 Satisfaction with surgery was similar for both management approaches, but significantly more subjects preferred the injection for overall experience.5The cataract experience continues to evolve as new technology allows for greater accuracy, greater convenience and faster recovery times. ■

| 1. Jabbarvand M, Hashemian H, Khodaparast M, et al. Endophthalmitis occurring after cataract surgery: outcomes of more than 480,000 cataract surgeries, epidemiologic features, and risk factors. Ophthalmology. 2016 Feb;123(2):295-301. 2. Hughes DS, Hill RJ. Infectious endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994 Mar;78(3):227-32. 3. Rhee MK, Mah FS. Cataract drug delivery systems (dropless vs. nondropless cataract surgery). Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2016 Summer;56(3):117-36. 4. Tyson SL, Bailey R, Roman JS, et al. Clinical outcomes after injection of a compounded pharmaceutical for prophylaxis after cataract surgery: a large-scale review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016 Sep 20. [Epub ahead of print] 5. Fisher BL, Potvin R. Transzonular vitreous injection vs a single drop compounded topical pharmaceutical regimen after cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016 Jul 18;10:1297-303. 6. Stringham JD, Flynn HW Jr, Schimel AM, Banta JT. Dropless cataract surgery: What are the potential downsides? Am J Ophthalmol. 2016 Apr;164:viii-x. 7. Galloway MS. Intravitreal placement of antibiotic/steroid as substitute for postoperative drops after cataract surgery. Presented at the American Society for Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (ASCRS) Annual Meeting. April 25-29, 2014. Boston, MA. 8. An JA, Kasner O, Samek DA, Lévesque V. Evaluation of eyedrop administration by inexperienced patients after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014 Nov;40(11):1857-61. 9. Reichle ML. Complications of intravitreal steroid injections. Optometry. 2005 Aug;76(8):450-60. 10. Quiram PA, Gonzales CR, Schwartz SD. Severe steroid-induced glaucoma following intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Mar;141(3):580-2. 11. Goñi FJ, Stalmans I, Denis P, et al. Elevated intraocular pressure after intravitreal steroid injection in diabetic macular edema: Monitoring and management. Ophthalmol Ther. 2016 Jun;5(1):47-61. 12. Chin EK, Almeida DR, Velez G, et al. Ocular hypertension after intravitreal dexamethasone (OZURDEX) sustained-release implant. Retina. 2016 Nov 1. [Epub ahead of print] |