Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification is a rare, benign condition generally affecting older to middle-aged whites.1-7 This condition is characterized by calcific, yellow-white elevated lesions commonly found in the superior temporal fundus. Although these benign lesions are commonly outside the foveal zone and usually have no impact on the patient’s vision, it’s important to differentiate them from presentations with a similar appearance, such as choroidal neoplasms, inflammatory lesions and lesions associated with systemic conditions.1-4,6-8

This case report describes a patient who presented to the clinic with this unique and rare condition. It also includes an overview of idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification and the process by which differential diagnoses and systemic associations are ruled out.

| |

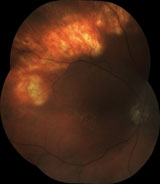

| This patient had significantly elevated, denticulated, yellow, mid-peripheral lesions located just beyond the superior temporal arcade in both eyes. |

History

An 81-year-old white male presented for a second opinion of his ocular condition. He reported that his local optometrist told him he has “mountains in his eyes.” He complained of mild blur only at intermediate distances and occasional ocular itching.

His medical history was significant for Type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and aortocoronary bypass surgery due to coronary artery disease. His medications included hydrochlorothiazide, metformin, nitroglycerin, losartan and simvastatin.

Diagnostic Data

The patient’s best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20-1 OD and 20/20 OS with compound hyperopic astigmatic correction.

Intraocular pressures measured 15mm Hg OU. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable. The patient’s posterior chamber intraocular lens implants were centered bilaterally, without posterior capsule opacification.

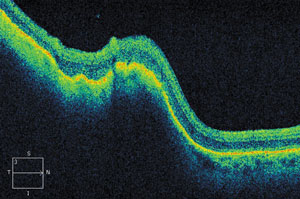

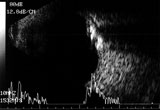

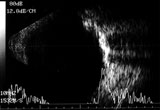

Dilated fundus examination revealed multiple hard and soft confluent drusen of the macula consistent with non-exudative age-related macular degeneration. Peripheral ophthalmoscopy revealed significantly elevated, denticulated, yellow, mid-peripheral lesions at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), located just beyond the superior temporal arcade in both eyes. Fundus photos and ocular coherence tomography, obtained at this initial visit, demonstrated the contour of these lesions. In addition, B-scan ultrasonography showed highly reflective choroidal elevations ranging in thickness from 1mm to 3.5mm with acoustic shadowing. There was no intra-retinal fluid, and the RPE and neurosensory retina were intact.

After reviewing these images, we understood why these elevated ridges were described to the patient as “mountains in his eyes.”

Diagnosis

The bilateral, symmetric, superior temporal location of these lesions, and their elevated calcific appearance without inflammation, helped to differentiate this condition from choroiditis and choroidopathies. The highly reflective choroidal elevations with echogenicity and acoustic shadowing, along with the lack of intra-retinal fluid on B-scan ultrasonography, led to the provisional diagnosis of sclerochoroidal calcification.

However, an evaluation by a retinal specialist and fluorescein angiography were further indicated to help rule out possible intraocular tumors. Lab testing was also needed to rule out systemic etiology.

Treatment and Follow-Up

We referred the patient to a local retinal specialist for further evaluation and fluorescein angiography. Fluorescein angiography showed early phase hypofluorescence of the lesion, with late stage hyperfluorescence without leakage at any stage. No secondary circulatory patterns were present, which helped to rule out a possible intraocular neoplasm. The retinal specialist confirmed our diagnosis of sclerochoroidal calcification.

Following this, we ordered lab testing to screen for systemic associations. Tests included complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and purified protein derivative (PPD). Serological evaluations for human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis were ordered to differentiate infectious etiologies. Blood and urine testing for calcium, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium were completed to rule out metabolic disorders. Serum testing for parathyroid hormone and calcitonin levels were also performed.

All testing was negative, further defining the diagnosis as idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification.

No treatment was indicated for this patient, as no metabolic disorder was present. Follow-up was scheduled in six months to monitor for unlikely choroidal neovascular membrane formation and retinal detachment. The patient was educated on the condition and given an Amsler grid for home monitoring.

Discussion

The term idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification was first coined in the literature in 1989.8 Limited data exists on the prevalence of this condition. A recent retrospective study led by Carol L. Shields, MD, at Wills Eye Hospital found reports of only 179 eyes affected with sclerochoroidal calcification between 1983 and 2014.1 Most reported cases (79%) have been deemed idiopathic, and most occur in older whites.1-7

| |

| Ocular coherence tomography demonstrated the contour of the lesions seen upon initial ophthalmoscopy, and we understood why the patient described his condition as “mountains” in his eyes. |

The lesions caused by sclerochoroidal calcification are often geographic and multifocal but can also be small, round and isolated.1,4 They are typically raised or placoid with no overlying retinal involvement. Occasionally they are surrounded by choroidal atrophy. They are easily identified with ultrasonography or computerized tomography. On ultrasound, they are highly reflective with acoustic shadowing posterior to the lesion.1-4,6-8

Fluorescein angiography can also be helpful in making a diagnosis. The typical fluorescein pattern has early phase hypofluorescence followed by gradual late phase hyperfluorescence without leakage.2,7,10 Due to disruption of the choroid and RPE, choroidal neovascularization and serous retinal detachment have been associated with this condition.2,3,5,6,9-15 Biannual retinal evaluation is recommended to monitor for these rare complications, and patients should be advised to self-monitor vision with a home Amsler grid.3,4

Sclerochoroidal calcification can be further classified as metastatic or dystrophic. These terms are used to describe pathological calcification of body tissues.4,16 Metastatic calcifications are lesions that form secondary to irregular calcium and phosphorous metabolism.2-4,16-18 Dystrophic lesions are found in patients with normal serum calcium and phosphorus levels and are typically found in areas of organ tissue damage or necrosis.

Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification occurs in patients with normal calcium and phosphorus metabolism and is therefore termed a dystrophic calcification.6 This calcification is pathologically identical to the anterior calcification at the insertion of the horizontal rectus muscles known as senile scleral plaques, seen in older individuals. Researchers hypothesize that idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification has a similar mechanism, and is secondary to chronic movement of the oblique muscles at their corresponding insertion sites.2,4-6

Other causes of dystrophic sclerochoroidal calcification include chronic inflammation, trauma and senile degeneration of the sclera.4,6,18,19

Although the majority of sclerochoroidal calcifications are considered idiopathic, rare systemic associations do occur.1-7 These calcifications have been attributed to hyperparathyroidism, parathyroid adenoma, vitamin D toxicity, pseudohypoparathyroidism, pseudogout, Bartter syndrome and Gitelman syndrome.1,2,4,6,11,14,20,21 Initial laboratory testing to rule out these disorders may include serum and urine magnesium, potassium, calcium, alkaline phosphatase and phosphorus levels. Parathyroid hormone and calcitonin levels are also indicated.1 In the case of abnormal test results, an endocrinology referral may be indicated.22,23

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of sclerochoroidal calcification includes:

• Metastatic carcinoma must be ruled out, especially in patients with prior history of cancer. These lesions tend to be dome-shaped, creamy yellow, multifocal and are usually found inside the vascular arcades. They often have overlying serous retinal detachments. On diagnostic ultrasound, these lesions do not show signs of calcification, which include high reflectivity and significant shadowing beyond the surface of the lesion.2-4,6,7,9,24

• Choroidal melanomas and nevi are typically pigmented, unlike sclerochoroidal calcifications that are lacking in pigment. Although a melanoma may be amelanotic, it does not typically have overlying RPE dropout. Lack of calcification on ultrasonography is again the major diagnostic difference of these lesions. Melanomas also have internal vascularity visible on fluorescein angiography. Overlying retinal detachments are common in melanomas.2-4,6,7,9,24

• Choroidal osteoma is a common misdiagnosis of sclerochoroidal calcification. These orange-yellow placoid masses are found in younger adults and children. They are well defined and often located adjacent to the optic disc. The most notable differential of these lesions is that they are unilateral 80% of the time.2-4,6,7,9,24-28

• Intraocular lymphoma can present as raised multifocal or diffuse yellow lesions at the level of the RPE and therefore are sometimes confused with sclerochoroidal calcification. These patients typically have some form of systemic lymphoma and usually have an accompanying vitritis.3,4,6,7,24, 26,27,29,30

| |

| B-scan ultrasonography shows highly reflective choroidal elevations ranging in thickness from 1mm to 3.5mm with acoustic shadowing. There was no intra-retinal fluid, and the RPE and neurosensory retina were intact. These findings led us to a diagnosis of sclerochoroidal calcification. |

Other differentials of sclerochoroidal calcification may include inactive chorioretinitis, retinoblastoma, retinal astrocytic hamartoma, choroidal hemangioma and eccentric choroidal neovascular membrane. Patient demographics, the calcified nature of the lesion, ultrasound characteristics, lack of leakage on fluorescein angiography and typical location are all helpful in ruling out other diagnoses.2,4,6,7,9,24

Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcifications are benign, but must be distinguished from more serious vision- or life-threatening choroidal neoplasms and inflammatory conditions. Detailed fundus examination, B-scan ultrasonography, fluorescein angiography and serial photography are typically needed to differentiate these conditions. Systemic metabolic abnormalities should also be ruled out with laboratory testing.

Routine ocular follow-up is needed to watch for possible serous retinal detachments and choroidal neovascularization. The prognosis is good as these retinal lesions typically have few complications and minimal visual significance.1,2,4

Dr. Cordes and Dr. Perkins are attending optometrists at The Villages VA Outpatient Clinic, in The Villages, Fla., which holds academic affiliations with the Illinois College of Optometry, Indiana University, Nova Southeastern University and Western University of Health Sciences.

1. Shields CL, Hasanreisoglu M, Saktanasate J, et al. Sclerochoroidal calcification: clinical features, outcomes, and relationship with hypercalcemia and parathyroid adenoma in 179 eyes. Retina. Mar 2015;35(3):547-54.2. Wong CM, Kawasaki BS. Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification. Optom Vis Sci. 2014 Feb;91(2):e32-7.

3. Kim M, Pian D, Ferrucci S. Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification. Optometry. 2004 Aug;75(8):487-95.

4. Shields JA, Shields CL. CME review: sclerochoroidal calcification: the 2001 Harold Gifford Lecture. Retina. 2002 Jun;22(3):251-61.

5. Honavar SG, Shields CL, Demirci H, Shields JA. Sclerochoroidal calcification: clinical manifestations and systemic associations. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001 Jun;119(6):833-40.

6. Schachat AP, Robertson DM, Mieler WF, et al. Sclerochoroidal calcification. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992 Feb;110(2):196-9.

7. Sivalingam A, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification. Ophthalmology. 1991 May;98(5):720-4.

8. Lim JI, Goldberg MF. Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification. Case report. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989 Aug;107(8):1122-3.

9. Pakrou N, Craig JE. Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification in a 79-year-old woman. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006 Jan-Feb;34(1):76-8.

10. Yohannan J, Channa R, Dibernardo CW, et al. Sclerochoroidal calcifications imaged using enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012 Jun;20(3):190-2.

11. Wong S, Zakov ZN, Albert DM. Scleral and choroidal calcifications in a patient with pseudohypoparathyroidism. Br J Ophthalmol. 1979 Mar;63(3):177-80.

12. Dedes W, Schmid M, Becht C. [Sclerochoroidal calcifications with vision-threatening choroidal neovascularisation]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2008 May;225(5):473-5.

13. Miller K, Eller A. Sclerochoroidal calcifications: wide-field imaging. Semin Ophthalmol. 2009 Jan-Feb;24(1):5-8.

14. Bourcier T, Blain P, Massin P, et al. Sclerochoroidal calcification associated with Gitelman syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999 Dec;128(6):767-8.

15. Leys A, Stalmans P, Blanckaert J. Sclerochoroidal calcification with choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000 Jun;118(6):854-7.

16. Howes E Jr, Rao N. Basic Mechanisms In Pathology. Calcifications. In: Spencer WH, ed. Ophthalmic Pathology: An Atlas and Textbook, 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1996:2948-9.

17. Boutboul S, Bourcier T, Laroche L, et al. Familial pseudotumoral sclerochoroidal calcification associated with chondrocalcinosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004 Aug;88(8):1094-5.

18. Munier F, Zografos L, Schnyder P. Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification: new observations. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1991 Oct-Dec;1(4):167-72.

19. Saatci A, Kaynak S, Kazanci L, et al. Calcification at the posterior pole in scleritis. A case report. Int Ophthalmol. 1996-1997;20(5):285-7.

20. Berkow J, Fine B, Zimmerman L. Unusual ocular calcification in hyperparathyroidism. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968 Nov;66(5):812-24.

21. Walsh F, Murray R. Ocular manifestations of disturbances in calcium metabolism. Am J Ophthalmol. 1953 Dec;36(12):1657-76.

22. Wysolmerski JJ, Insogna KL. The Parathyroid Glands, Hypercalcemia, and Hypocalcemia. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Cecil Medicine, 24th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011: ch. 253.

23. Bringhurst FR, Demay MB, Kronenberg HM. Hormones And Disorders Of Mineral Metabolism. In: Kronenberg HM, Schlomo M, Polansky KS, Larsen PR, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 12th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011: ch. 28.

24. Shields JA, Shields CL. Differential Diagnosis of Posterior Uveal Melanoma. In: Shields JA, Shields CL. Intraocular Tumors: A Text and Atlas. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992:137-53.

25. Shields C, Shields J, Augsburger J. Choroidal osteoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988 Jul-Aug;33(1):17-27.

26. Goldstein BG, Miller J. Metastatic calcification of the choroid in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism. Retina. 1982;2(2):76-9.

27. Wiesner PD, Nofsinger K, Jackson WE. Choroidal osteoma: two case reports in elderly patients. Ann Ophthalmol. 1987 Jan;19(1):19-23.

28. Gass JD. New observations concerning choroidal osteomas. Int Ophthalmol. 1979 Feb;1(2):71-84.

29. Davis JL. Intraocular lymphoma: a clinical perspective. Eye (Lond). 2013 Feb;27(2):153-62.

30. Kimura K, Usui Y, Goto H; Japanese Intraocular Lymphoma Study Group. Clinical features and diagnostic significance of the intraocular fluid of 217 patients with intraocular lymphoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012 Jul;56(4):383-9.