Millions of Americans suffer from a traumatic brain injury (TBI) each year, with nearly 75 percent of all those with TBI suffering from some form of visual dysfunction.1 Patients may come into the primary care optometrist’s office complaining about double vision, blurred vision, closing one eye, dizziness, headaches, sensitivity to lights, bumping into things and/or poor coordination.

Visual symptoms of a concussion include visual acuity problems, visual field loss, oculomotor dysfunction, convergence and accommodative disorders, photophobia and reduced visual attention.1 A brain insult can also affect a person’s posture, balance, gross motor and fine motor skills, cognition, attention, concentration, learning, productivity and daily activities.

Although sight may begin with the eyes, it actually occurs in the brain. Over half of the brain is dedicated to vision and visual processing. There are many pathways in the brain that carry visual input from the eyes to the back of the brain where the visual cortex is located. Since vision involves so much of the brain, even a mild injury to almost any part of the brain can significantly impact the multiple processes involved in vision.

Patients with a mild TBI (mTBI), also known as a concussion, should be seen by their optometrist for an evaluation and appropriate vision rehabilitation treatment, as optometrists are essential in the rehabilitation process.

|

| TBI patients can use a saccadic fixator for oculomotor therapy. Click image to enlarge. |

At-risk Patients

The top two reasons for TBI are unintentional falls, which accounted for almost 50% of all TBI-related emergency room visits in 2014, and being struck by an object, which accounted for nearly 20%.2 Motor vehicle accidents, assaults, explosions and sports injuries can also cause a TBI. While many of these are not preventable injuries, it is well within the purview of the primary care optometrist to talk about them with susceptible populations.

Besides the high-risk populations of athletes, first responders and military personnel, consider collecting baseline tests on all patients for a comparison if an injury does occur.

For the elderly, optometrists can address their maturing visual function and suggest environmental adaptations, such as lighting and contrast changes. Provide parents of small children with additional guidance, and educate them of the safety precautions for cribs that children can climb out and the value of placing gates at stairwells.

Remind older children of the increased risk ofTBI when they fall and are not wearing a helmet on bikes, scooters and skateboards, as well as the importance of wearing helmets in all sports that offer them.

All age groups should wear seat belts in moving vehicles, and first responders and military personnel should always wear their protective equipment.

|

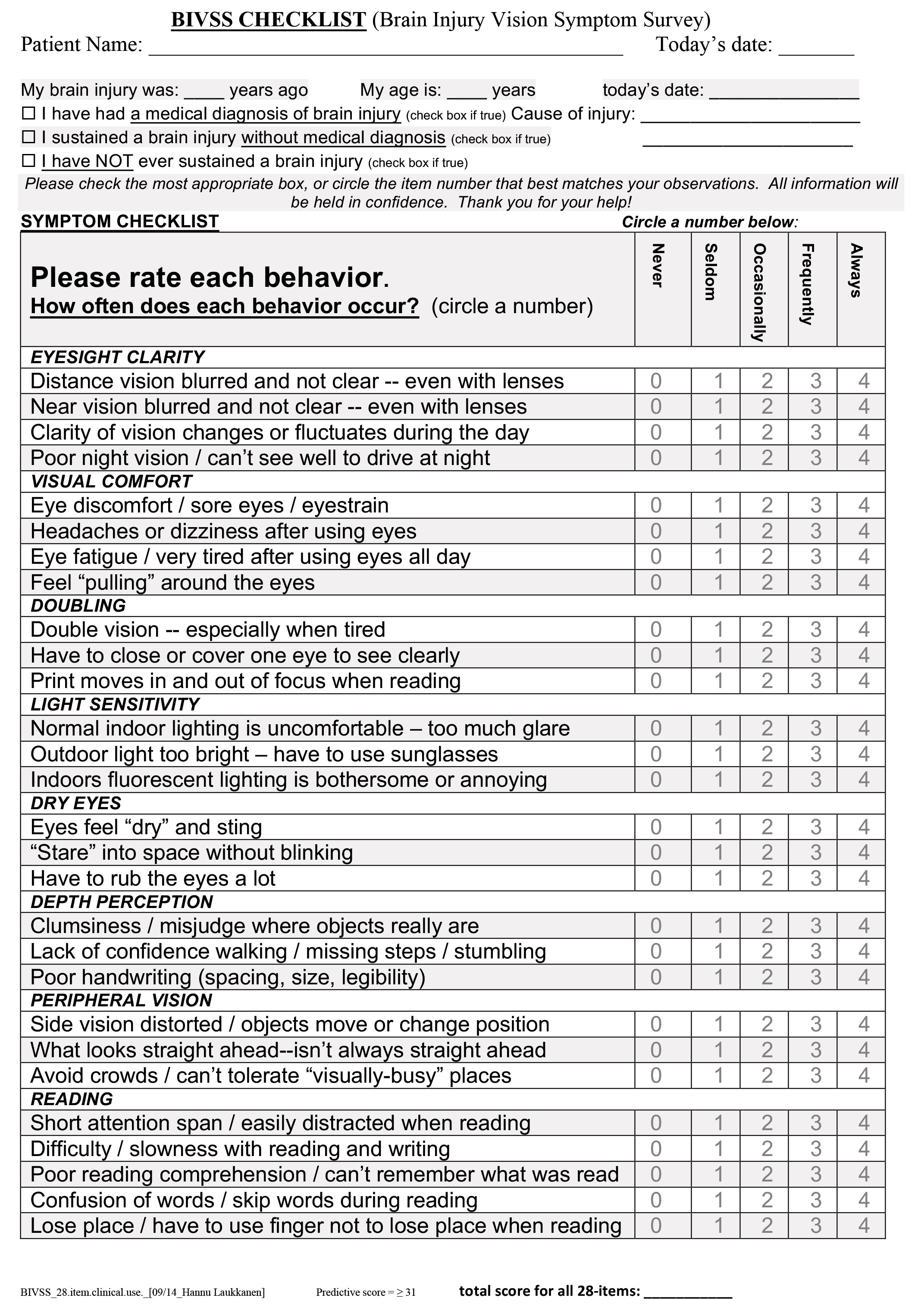

| Having the patient fill out the Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey before their appointment will allow them to answer the questions at their own pace. Click image to download. |

In-office Exam and Care

Unfortunately, many optometric interactions with patients often come well after the injury. Fortunately, there’s a growing body of evidence that shows optometrists can play a key role in helping identify if a concussion has occurred, providing treatment and monitoring how well the patient is progressing in their recovery.3

When caring for a concussion patient, observe the effects of vision deficits possibly related to the head injury. Allot extra time when scheduling patients with concussions, as they may have difficulties during the examination due to fatigue, dizziness, light sensitivity or attentional issues. When these occur, frequent breaks can help make the patient more comfortable and may lead to more accurate and productive testing. Be aware that, sometimes, the examination needs to be done in a dark or dim environment, while other times, normal room lighting is acceptable.

A comprehensive eye exam provides baseline measurements for a concussion and also serves as an entry point for a more formal concussion workup by a primary care optometrist if ever needed. During the initial comprehensive eye exam, take a detailed history and evaluate visual acuity, visual fields, pupils, stereopsis, color vision, cover test and eye movements (saccades, pursuits, near point of convergence, Developmental Eye Movement test). Also conduct retinoscopy/refraction, binocular and accommodative measurements (vergences, phorias, fixation disparity, near accommodative flippers and amplitude of accommodation), a slit lamp evaluation, intraocular pressure testing and a dilated retinal evaluation.

|

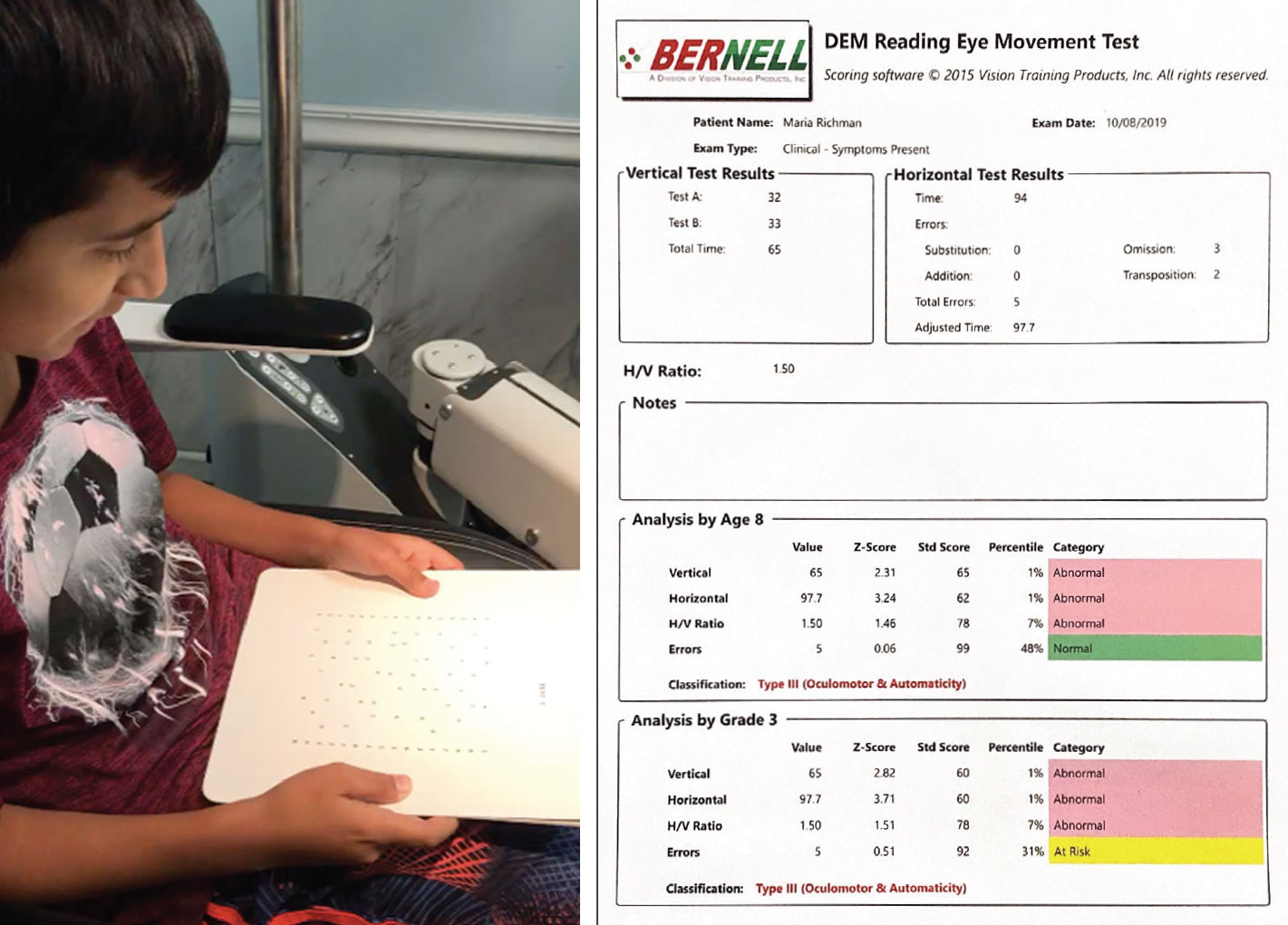

| A pediatric patient takes the DEM test (left). This sample of the reading eye test’s results note oculomotor dysfunction and reduced attention (right). Click image to enlarge. |

During an exam, focus on these areas:

History. Patients may report blur at distance or near, headaches, dizziness, visual discomfort, double vision, dry eye, light sensitivity, depth perception issues, peripheral vision complaints and reading-related issues. These areas are addressed in the Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey, a standardized survey developed by the Pacific University College of Optometry.4 You can mail this survey and the intake/history form to the patient at the time of scheduling the appointment or present them with it when they arrive at their appointment. Mailing the items in advance will give the patient and/or caregiver time to complete them at their leisure.

Visual acuity issues. Patients may complain about intermittently blurred vision. In these cases, a minimal prescription may be effective following retinoscopy and a refraction. Another cause of intermittent blurred vision is tear film instability. At this point, consider a dry eye evaluation that includes a blink evaluation. TBI patients may have a delayed blink reflex, an incomplete blink reflex or no blink reflex at all. Consider that the blink rate may be low (compared with 17 blinks per minute) when measuring.5 Note that TBI patients may have a blank stare as they are processing their visual information. This stare can induce or exasperate a dry eye. Testing for dry eye can lead you to treating the poor quality of the refractive surface, which, in turn, will increase the patient’s visual acuity stability.

Visual field loss. While not as common in concussion cases, more advanced TBI patients may bump into things or miss items in their peripheral field of vision. Once confrontation fields document a defect, confirm it with standardized, computerized field testing. This will narrow down the level of impairment, as defined by the Social Security Administration, and also document any future improvement. If appropriate, consider prisms or rehabilitation therapy (whether vision, neuro-optometric, sports or physical medicine) either in your office or refer out to an optometrist who has special interests in that area. Unfortunately, computerized visual fields may be difficult in some cases since visual field testing is dependent on attention, and this population may have attention deficits, reduced speed of processing and/or a delay in reaction time.

If the patient is within their first year and a half of recovery and you can measure visual fields initially, repeat testing in six months to note any improvements. While traditional visual field loss is usually irreversible, this population demonstrates it may be possible to recover some field loss within that early time period.6 This is due to neural plasticity, and the use of the prisms or therapy may contribute to improvements in visual attention, spatial awareness and ultimately visual fields. Keep in mind each case is very different, and sometimes the original visual field loss remains the same.

|

| TBI patients can use tinted lenses and a brimmed hat to reduce photophobia. Click image to enlarge. |

Oculomotor dysfunction. TBI patients may exhibit reduced or altered saccades, pursuits and/or other near point convergence irregularities. Use a quick eye movement test, such as the Developmental Eye Movement (DEM) test, to quantify the level of impairment. This test measures number-naming speed and differentiates language processing speed from oculomotor dysfunctions, which may be quite helpful in the treatment plan. The DEM allows for better specificity of oculomotor dysfunctions than the King-Devick test, as it eliminates the language speed and potential oral injuries from the calculation. The test may also assist in documenting improvements made following optometric vision therapy treatment. As every patient is different and every concussion impacts the brain differently, some people need to start slow while others can be pushed to work on higher-level activities.

Accommodative disorders. Problems focusing at near often benefit from eyeglasses and vision therapy. It has been found that even small amounts of plus lenses (as small as +0.25D) can have a profound impact on this population.7 Consider additional investigation on binocular balance at near, as unequal adds are sometimes warranted. Addressing these accommodative issues may also improve convergence and visual attention abilities.

Photophobia/glare issues. Primary care optometrists can respond immediately to these by recommending sunglasses, special tints, transitions, a brimmed hat or limited outdoor activities. While there are many lens options, specific wavelengths seem to work best for certain patients. Prescribing lenses usually includes a sequential assessment of various tints, which will ultimately result in the best color/transmission/wavelength/design for the individual patient.

Reduced visual attention/perception skills. When patients demonstrate that they are distracted by less relevant information when trying to attend to something, they may be exhibiting reduced visual attention. If these issues last more than a few weeks, it’s time to consider vision therapy, specifically visual processing therapy treatment options. If this service is not provided in your office, have your patient serviced at an optometric office that does.

When patients complain of trouble copying text, reversing letters or words, poor reading comprehension, confusing directions and difficulty telling right and left, consider standardized testing and vision therapy activities. These too should be done in your office or you should work with an optometric colleague who will share in the care of your patient for these specific activities.

Helpful ResourcesFor more information, there are many organizations that provide education on brain injuries for optometrists. The American Optometric Association (AOA) Vision Rehabilitation Committee and the Brain Injury Task Force have developed guidelines, manuals, briefs and articles to assist their members. There are opportunities at the national level of the AOA and its state affiliates to become active in their respective Vision Rehabilitation Sections and Committees. In addition to the AOA’s resources (aoa.org/VR), there are other organizations, such as the College of Optometrists in Vision Development (covd.org), the Neuro-Optometric Rehabilitation Association (noravisionrehab.org), the American Academy of Optometry (aaopt.org) and the Optometric Extension Program Foundation (oepf.org), that offer tremendous education to practitioners and patients alike. |

Comanage and Educate

Optometrists routinely perform much of the necessary baseline information in a comprehensive exam, such as visual acuity, pupils, visual fields, accommodative amplitude, saccades, binocular measurements and more. These findings are valuable to in evaluating, diagnosing and managing treatment of the visual sequelae of concussion. Optometrists in primary care practices who identify these visual disorders and dysfunctions have the option to provide additional testing and care during their patient’s evaluations and eventual rehabilitation or refer these cases to an optometrist who can.

However, comanagement within the optometric community is not enough. It is equally important to coordinate care with other members of the TBI care team, such as the physiatrist, neurologist, neuropsychologist, medical physicians, occupational therapist, physical therapist, speech therapist and nurses. As a member of the traumatic brain injury rehabilitation team, the optometrist’s role increases the overall effectiveness of and may even reduce the time needed in the rehabilitation program, which is highly dependent upon vision.

After diagnosis, the optometrist can direct the other members of the rehab team in regards to treating visual dysfunction and providing rehabilitation options. In addition to working with the TBI care team, optometrists should educate the members of their community. While primary care optometrists are very good at servicing their own patients, promote the importance of gathering baselines pre- and post-concussion information to school nurses and coaches, sports teams and others. Also, educate the public and other healthcare professions on the importance of eye and vision health in reducing the impact and risk of TBI, and encourage helmet use, seat belts, area carpets, proper gates by stairwells and more. This does not only promote our profession to our local community but doing so also can quite likely improve care and treatment by providing higher quality outcomes for all of our patients.

Dr. Richman practices as a low vision and vision rehabilitation optometrist at Shore Family Eyecare in Manasquan, NJ. She currently is a member of the AOA Traumatic Brain Injury Task Force and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Optometry.

| 1. Ciuffreda KJ, Kapoor N, Rutner D, Suchoff IB, Han ME, Craig S. Occurrence of oculomotor dysfunctions in acquired brain injury: a retrospective analysis. Optometry 2007;78(4):155-61. 2. CDC. TBI: get the facts. CDC Traumatic Brain Injury & Concussion. www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/get_the_facts.html. March 11, 2019. Accessed May 8, 2020. 3. Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ. Assessment of neuro-optometric rehabilitation using the Developmental Eye Movement (DEM) test in adults with acquired brain injury. J Optom. 2018;11(2):103-12. 4. Laukkanen H, Scheiman M, Hayes JR. Brain injury vision symptom survey (BIVSS) questionnaire. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94(1):43-50. 5. Bentivoglio AR, Bressman SB, Cassetta E, et al. Analysis of blink rate patterns in normal subjects. Mov Disord. 1997;12(6):1028-34. 6. Matteo BM, Viganò B, Cerri CG, Perin C. Visual field restorative rehabilitation after brain injury. J Vis. 2016;16(9):11. 7. Green W, Ciuffreda KJ, Thiagarajan P, et al. Accommodation in mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(3):183-99. |