It goes without saying that having the right diagnostic tools in your office is important to treat dry eye, but there’s something else that’s just as critical to ensuring a successful outcome for all of your patients: communication. If they don’t fully “hear” what we say, they’ll fail to understand and commit to treat their condition. Understanding chronicity and the patient commitment to themselves is necessary for any treatment to be effective. Considering that only about 12% of adults in the United States have good health literacy, we have to be very intentional about how we communicate.1

What exactly is health literacy? It’s the patient’s ability to collect and understand information on their health status so they can make the best decisions for their unique situation. Since dry eye is highly prevalent and a chronic disease, this article will share how I present concepts of dry eye, build ocular surface health literacy and convey the responsibilities of the patient in a way that encourages adherence to my therapeutic plan.

|

Dr. McGee carefully communicates with her patient as they create a plan and discuss the steps that have to be taken to combat dry eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Communication is Key

As author Stephen Covey once said, “Begin with the end in mind.” The first step is to figure out what you want to accomplish with your dry eye patients. Developing a system for communication is very important. It’s not just what you say but how you say it. Ask yourself the following questions:

• Do I have a communication system?

• If so, where are the gaps?

• What’s working?

• More importantly, what’s not working?

I have found the key to communication in our office is consistently working on the same language delivered in a way that the patient wants the information. Words matter, delivery matters and known processes are vital; a breakdown anywhere along that chain diminishes your return on investment.

Imagine a patient hearing different words used by different team members: one person says dry eye, another says ocular surface disease and someone else says unstable tear film. How confused would the patient be when they left the office?

Remember, it’s not just you as the doctor delivering messaging. Every touchpoint in the office (and prior to the patient entering the office) is an opportunity to communicate. As you consider that, ask yourself these questions:

• Does my team understand the importance of dry eye?

• Do they know the consequences?

• Do they have the willingness to participate?

|

| Dr. McGee’s technicans are properly educated on dry eye, and in turn, help teach patients what they need to know during appointments. Click image to enlarge. |

Education Roadmap

I cannot overstate how important beginning the education process with your team first dictates how successful you will be when educating your patients.

In my office, we created a roadmap of the patient journey to determine where we needed to talk about dry eye. Once that was completed, we discussed and practiced what would be said and by whom.

First, we started with our digital footprint. We developed a wealth of information on our website for patients visiting us online before they came into the office, and we also direct patients back to the website if they need more information after their visit.

Next, our director of first impressions checks in the patient with a personalized greeting and a lifestyle questionnaire which includes sections specifically driven to gather symptoms of dry eye and educate the patient. When the patient is handed this form, our staff member also lets them know how prevalent and underdiagnosed dry eye is and why it’s so important they answer honestly.

Next stop on the roadmap is the technician. I have invested in supertechs in my office, meaning the technician that works up the patient also scribes for me with the patient. I like this system because anything that occurs during the workup doesn’t get lost in translation once I come into the exam, and I believe there is better continuity of care with this system. My technicians educate our patients every step of the way, explaining every diagnostic tool, what it is and why we perform it.

The way they ask questions to the patient is also key. How we phrase the questions can either expand the conversation or shut it down. Try to ask the questions so that “fine,” “yes” or “no” are not available answers. An example is, “Do you experience x, y or z?” The answer that is too easily given is yes, no or maybe. If the patient does answer yes, you can certainly expand on that with follow-ups like, “Tell me more,” “When does that occur?” or “What have you done about it?”

What happens if they answer no? You’ve effectively shut that conversation down. If you change that question with just one word, it makes a subtle difference: “When do you experience x, y and z?” The patient is going to be required to think about when that does happen. Maybe they only experience eyes that burn periodically or vision that fluctuates toward the end of the day. Once they elucidate their particular experience, everything that you talk about is driven toward helping that pain point.

When you become the person solving your patients’ symptoms, the conversation becomes two-sided. If we don’t do the legwork up to this point to find out what the patients’ pain points really are, all we do is try to convince someone to adhere to solutions for a problem they don’t even recognize they have. We have all had that experience in the chair with a patient who clearly has signs of dry eye, but because we never tied it to them personally—giving them the why and how it’s effecting their typical day—those conversations lead to frustration for both the doctor and the patient.

During examinations, I rely heavily on diagnostic tools to help me educate each patient. My tech workups help me expand upon the patient’s chief complaint and how I can best help them achieve an optimized vision and ocular surface plan. We use standing orders when a patient answers two or more symptom questions to perform MMP-9 and tear osmolarity testing; this is all performed before I walk into the room.

The refraction is a key component to not only helping patients achieve their best vision possible but also gives us many clues to their personality type as well as keeping your ears open for symptoms of dry eye. I’m listening for things like, “Wait, let me blink. Now it’s clearer.” That is a direct clue there is a problem that needs to be addressed. Explain to the patient why that blink is so important and remind them how their vision cleared when they blink. If we educate along the way, this helps the patient retain more information as well as save precious chair time.

|

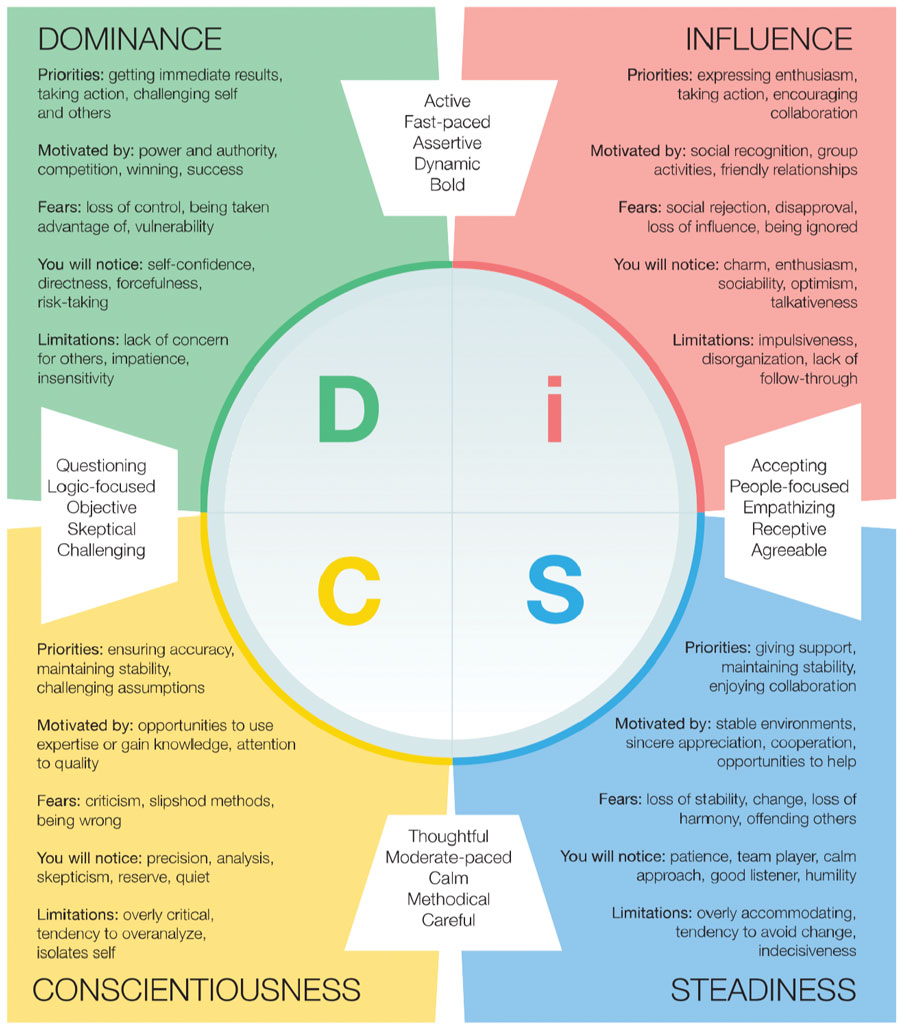

The DISC personality test can be an important tool when communicating with and understanding your patients. Click image to enlarge. |

Personality Profiles

Why do I care what type of personality my patient has? My goal is to truly connect with each patient, and to do that efficiently I lean on tools such as the DISC personality test. I have found that when I engage my listening skills and communicate with patients in the way they want to be communicated with, they feel heard, understood and are more likely to adhere to our dry eye plan because we’ve worked through it together. The way in which I educate each patient is different even though the content is the same. The tools I use to educate also cover all personality types so that there is something there for everyone and I can further customize it to each patient.

To simplify DISC, think of it this way: there are four types and most people have one strong tendency followed by a second. We each exhibit all four types at different times, but leaning into one may require more energy for that person. Think about the introvert at a party: they can be sociable, but may find the experience to be draining, and they will need to recharge before being at their best again. Each letter of the acronym stands for a personality; let’s review a simplified version:

• D (dominance) individuals are doers and they want information quickly without a lot of detail. They are the patients during the refraction that answer before you even explain what you want done, and answers are clear and concise.

• I (influence) people are those who like to talk, are often the life of the party and they are the patient that is still talking to you as you place the phoropter if front of their face. Typically, you can barely get a question in as they chat.

• S (steadiness) types are your “feelers.” They don’t like change and are very careful about the decisions they make. They will also use “feeling” language; listen hard for those cues. Often, behind the phoropter it comes out as, “I don’t want to choose, this is so hard. I feel like I failed this test.”

• C (conscientiousness)—the thinkers. These are the patients that need all of the information before making an informed decision. They may ask questions like, “Should I be looking at the O or the H? Should I choose the letters that are clearer or the ones that are easier to see?”

Based on the patient’s personality type, I then communicate towards that. As I move through the rest of the exam using meibography, photography, vital dye (lissamine green and sodium fluorescein), functionality of meibomian glands as well as ocular surface, I use what I’ve learned about the patient to explain as I go and educate.

For those who are in the “D” category, I don’t dwell and over-explain—I get right to the point. For those in the “I” category, I lean back and let them talk. For those in the “S” category, I lean in and make sure they are comfortable with the conversation, I speak slower and I shift my body language to convey a safe space. I pointedly ask for feedback from them. For those in the “C” category, I put on my patience hat and allow them to ask questions. I slow down and lean back in my chair instead of sitting on the edge of it ready to leap out of the room and on to the next patient.

All of these details matter to that patient. The words you choose, your body language and the “how” of your communication, along with the actual information, together make up the patient experience. In order for the patient to hear your dry eye education and what you want them to learn, you have to do it in way that is meaningful to them.

If you’re thinking this sounds like a lot of work, it is. It’s also worth the investment and will greatly improve your patients’ experience and the outcome.

|

Technicans discuss dry eye treatment options with patients. Click image to enlarge. |

Managing Dry Eye Properly

Once the exam is complete, I give patients written information to take home. This includes a handout with clear photos and explanations of our therapeutic options, with everything from visual hygiene, home therapy (warm compresses, lid seals), medications (Xiidra, Restasis, Cequa) and in-office procedures (LipiView, iLux, TearCare). I simply check what that patient is going to do between now and the next time I see them.

For a new dry eye patient, I am careful to explain what to expect. Dry eye is a chronic disease that we will manage together; we will start with step therapy and follow up in four weeks to see if we need to add additional therapies or if the patient is fully managed. It’s important to follow up—I never let a dry eye patient go longer than six months, even when well-managed.

Before leaving the room, I am careful to go through what prescriptions I write (not recommendations—remove that word from your patient dialogues) and ask, “Do you have any questions for me? Did we accomplish everything you wanted to achieve?” Then, my scribe takes over, walking the patient through more detail and answering any other questions that may arise. They finish with tying everything back to the “why.”

For myself and the other doctors that work in my practice, we have a standard protocol based on what level of dry eye disease the patient has. We have four levels of disease and we all are using our diagnostic tools and therapeutics in the same way, with the same language. This is very important for continuity of care and I want our patients to have the same experience no matter which doctor they see.

|

Dry eye patients need ongoing patient education and encouragement to stay the course of treatment and self-care. Click image to enlarge. |

Takeaways

When you first start putting these kinds of systems into place, it can daunting, but layering education throughout the entire patient experience and empowering your team to build the systems with you are what make this doable. It may feel clunky and uncomfortable, but that’s when you know you’re doing the right thing. Eventually, you will become unconsciously competent and create your system.

Effectively educating our patients and our team will give patients the control to take better care of themselves. Communication is a lifelong skill that we all must be intentional about and continue to improve upon to give our patients, practices and profession every opportunity for success.

Dr. McGee is founder and owner of BeSpoke Vision, a boutique private practice that offers patients a wide range of optometric care via its dry eye center, specialty contact lens clinic and aesthetics suite. She is also an adjunct assistant professor at the Northeastern State University College of Optometry and on faculty at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation at its Sjögren’s clinic. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Optometry, a Diplomate of the American Board of Optometry and is past president of the Oklahoma Association of Optometric Physicians. Dr. McGee consults for Allergan, Kala Pharmaceuticals and Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

1. America’s Health Literacy: why we need accessible health information. www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/health-literacy/dhhs-2008-issue-brief.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2022. |