|

A 64-year-old Caucasian female presented as a new patient after her previous eye care provider retired. She complained of long-standing blurred vision, relatively equal between the two eyes. She also reported chronic blepharitis and dry eye diagnoses, with blepharitis flare-ups on the rise. She had been given a long term prescription for neo-poly-dex drops to use when the blepharitis flared and has been using them about once a month, for approximately a week, twice a day. She had undergone LASIK surgery approximately 18 years prior. She was also taking simvastatin 80mg QD, multivitamins, calcium glucosamine and magnesium daily. She reported that her son had been diagnosed with glaucoma a few years earlier.

Her last visit to her previous provider was a year earlier, at which time she was told the blurry vision was related to her dry eyes as well as, apparently, some ‘changes’ to her corneas following the LASIK surgery.

At the initial visit, best-corrected visual acuities (BCVA) were 20/25-2 OD and 20/30-2 OS. Confrontation fields were slightly restricted superiorly, which I initially attributed to her dermatochalasis.

|

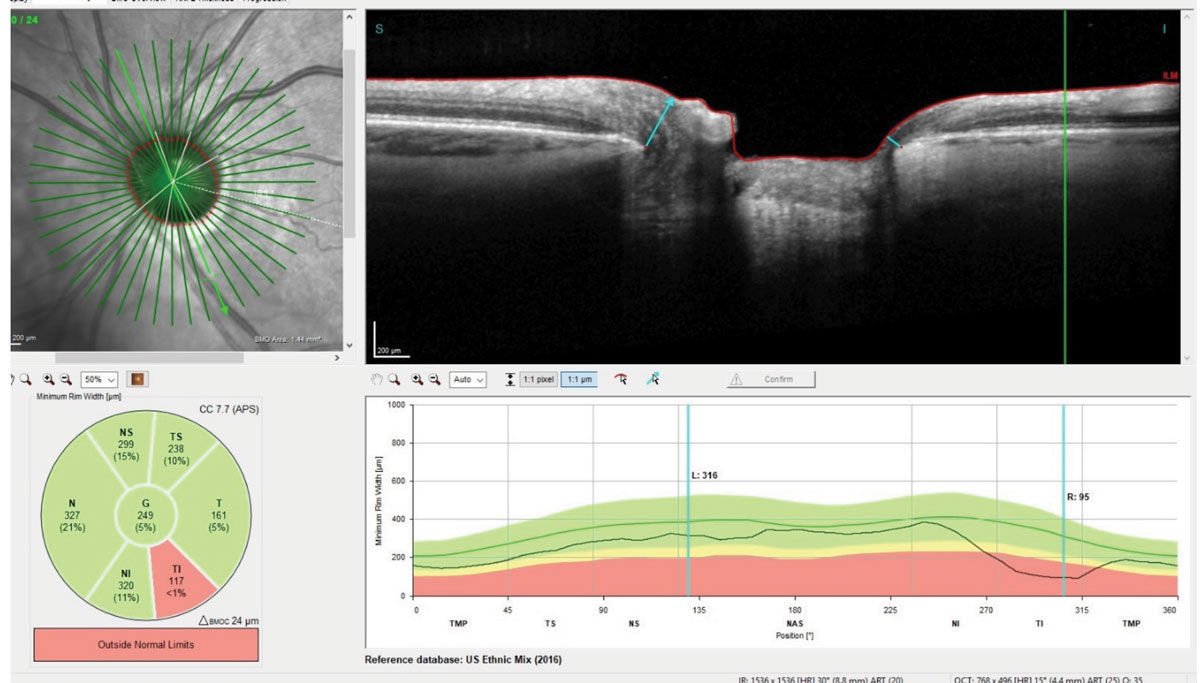

| Fig. 1. Bruch’s membrane opening display of the patient’s left eye demonstrating erosion of the left inferotemporal neuroretinal rim. Note at the marked area the neuroretinal rim is only 95µm thick at that point. |

Evaluation

A slit lamp examination of her anterior segments was remarkable for clear post LASIK flaps, with no evidence of striae, epithelial ingrowth or other physical aberration to both corneas. The anterior chamber angles were open and the anterior chambers were quiet. Applanation tensions were 12mm Hg OD and OS at 2:42pm. Through dilated pupils her crystalline lenses were characterized by incipient nuclear sclerosis, but not to the level to account for the 20/30-2 BCVA. Pupils were ERRLA with no afferent pupillary defect.

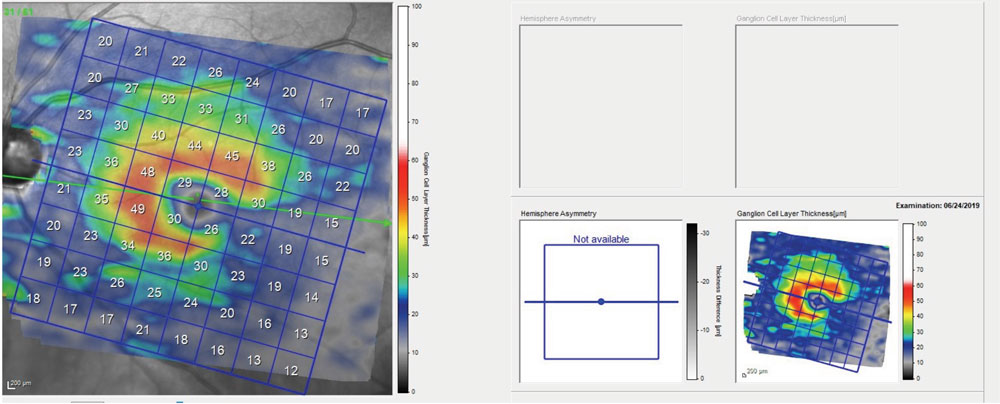

Stereoscopic examination of her optic nerves demonstrated eroded neuroretinal rims in both eyes, with the right showing more thinning than the left. The remaining, thinned neuroretinal rims were plush and perfused. The cup-to-disc ratios were 0.70 x 0.85 OD with an exceedingly thin neuroretinal rim from 6 o’clock to 9 o’clock, and 0.60 x 0.75 OS with an eroded rim from 3 o’clock to 6 o’clock. Peripapillary atrophy was evident in both eyes.

Her macular evaluations were essentially unremarkable. Her vascular appearance was consistent with mild arteriolarsclerotic retinopathy in both eyes, and her peripheral retinal evaluations were remarkable for 360 degrees of cystoid and scattered areas of pavingstone degeneration.

During the fundus examination, it was clear that her optic nerves were not healthy, and with the erosion of the neuroretinal rims to the extent they were, my initial impression was that she most likely had visual field loss involving fixation. Given her relatively low IOP, the differential of normal tension glaucoma arises, which has connotations of possible neuro-ophthalmic etiologies. This instigated a closer re-evaluation of the optic nerves, which, on second view, demonstrated normal size optic nerves, no evidence of edema or elevation, and in particular no evidence of pallor.

The previous LASIK is also playing a role in the low IOP readings, as contrasted to the optic nerve appearance. Pachymetry measurements were obtained, and the central corneal readings were 487µm OD and 470µm OS. When asked, she reported that she was fairly myopic prior to the LASIK, and when pressed for an estimate of her contact lens powers, she reported that they were in the -9.00 range OU.

|

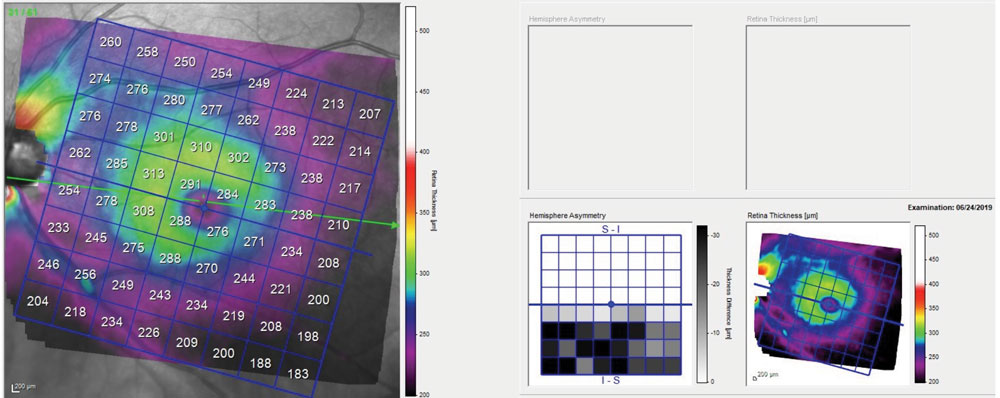

Fig. 2. Total macular thickness of the left eye, demonstrating thinning of global retinal indices inferotemporally. Note the evident difference on the asymmetry map between the superior and inferior macular hemispheres. |

Diagnosis

At this point, the case seems to be pretty straightforward of undiagnosed glaucoma. Exceedingly straightforward in fact. A high myope undergoes LASIK surgery OU, with resultant thin corneas and resultant low IOP readings by applanation tonometry. The extent of her optic nerve damage indicated that the damage did not occur in the last six to 12 months. Even though the patient was using a drop containing dexamethasone off and on for an extended period of time, IOP readings at the initial visit were not indicative of a significant steroid response.

Could IOPs have been significantly high for a long enough period of time to cause the neuroretinal rim damage? While it’s possible, she only used the steroid infrequently. Even though one can argue that a corrected IOP would be higher than that seen in clinic, the evidence is clear that the neuroretinal damage occurred over time. And certainly it would have been present at the time of her last visit to her previous eye care provider.

|

| Fig. 3. This macular image demonstrates significant thinning of the ganglion cell layer contiguous with the eroded inferotemporal neuroretinal rim as seen in Figure 1. |

Managing the Mismanaged

We have all been in a scenario where a patient appears to have been mismanaged. While we often we give another provider the benefit of the doubt, in this case the prior provider was a militant anti-optometry crusader who, as a result, received few OD referrals over their career and, partly as a result, their surgical outcomes suffered. Do you handle this any differently than any other case where we suspect someone dropped the ball? Do we undermine the other doctor’s reputation? No. Though it’s tempting to react, it serves no purpose, especially to the patient. Treat this patient like any other. Explain your findings, make no excuses for the disease and explain your management plan. In this case, I asked the patient to return to clinic in a couple of weeks for threshold fields, optical coherence tomography and Heidelberg retina tomograph optic nerve imaging, as well as gonioscopy.

When the patient asks why their previous doctor didn’t catch the disease, I would encourage you not to trash the other provider, as that may only serve the purpose of making the new-to-you patient feel uncomfortable with your bedside manner. For those providers whom I respect, and for whom I understand will occasionally have a case head south, I usually reply something like: “Well, Dr. X is a competent doctor and your condition is difficult to diagnose. It’s probable your condition was not manifest when you last saw them.” For others, where I may find it hard to be complimentary, I may reply similarly to this: “Well, I’m not sure exactly what Dr. X was seeing at that time, but this is what you have now and this is how I’m going to care for you.”

Did I throw the previous doctor under the bus? No, I redirected, took control of the discussion and told the patient what I would do for them. It’s actually quite an effective tactic, especially when a new-to-you patient has been seeing a different provider and you’re delivering news they have not heard previously.

Remember, our duty is to the patient and the profession. Treat each patient as you would want to be treated. Is it in a patient’s best interest to be seen by a provider who is very anti-optometry? No, but neither is it in their interest to hear you grouse about organized medicine.

The provider in this patient’s earlier care was someone who did not respect optometry, did not work with optometry and who at every occasion took the opportunity to disparage optometry. When the shoe is on the other foot, don’t be like them! We can work around providers like that and still care for the patient.