|

A 19-year-old female was referred for suspicion of papilledema. She was first diagnosed with the condition 1.5 years prior. At three different ophthalmic exams over the preceding 18 months, both her referring optometrist and an ophthalmologist recommended she undergo neuroimaging studies. Despite their suggestions, she did not pursue further work-up and was lost to follow-up.

|

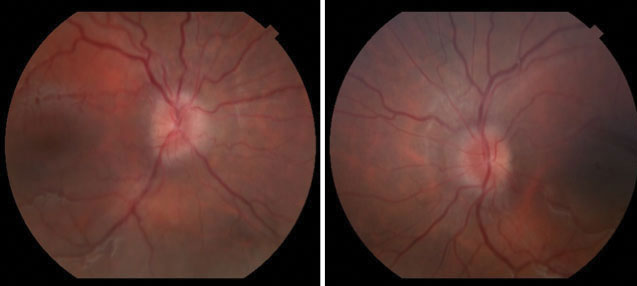

| Fig. 1. Fundus photographs at the initial visit revealed mild bilateral optic nerve edema. Click image to enlarge. |

Examination

Upon presentation, the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity was 20/25 in both eyes without an afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motilities were unremarkable. Intraocular pressures were 26mm Hg OD and 27mm Hg OS. Her blood pressure was 146/83 and body mass index (BMI) was >30. She did not have a fever.

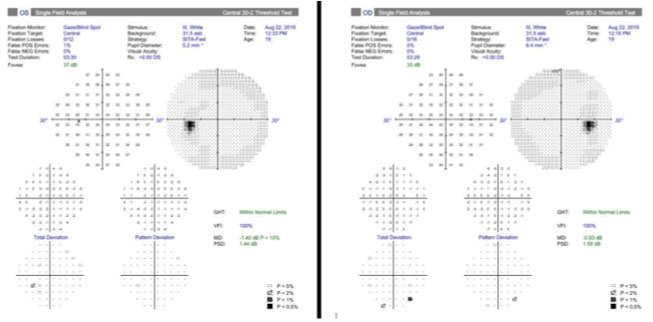

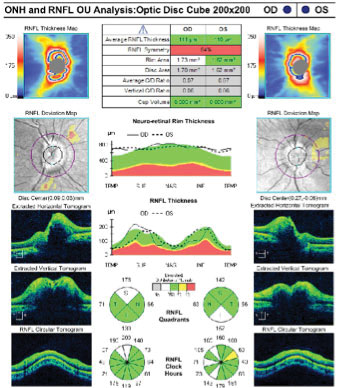

Slit lamp exam of the anterior segment was unremarkable. The dilated fundus examination revealed nasal elevation of the optic nerve in both eyes without spontaneous venous pulsation (Figure 1). Visual fields and OCT are available for review (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient denied transient visual obscurations, diplopia, medication use (tetracycline, birth control) and hypertension. She endorsed mild pulsatile tinnitus, which worsened upon lying down, moderate daily headaches and recent weight gain of about 30lbs over the past year.

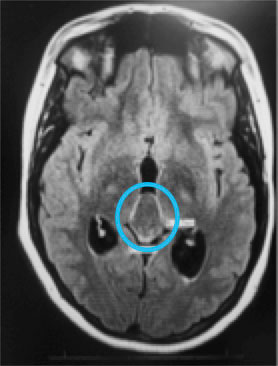

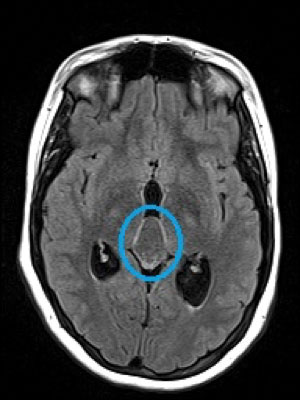

Given our clinical exam findings and the patient’s symptom profile, we ordered MRI with and without contrast and magnetic resonance venography. Radiological review of the neuroimaging revealed enlarged ventricles, partially empty sella and a 2.97cm-by-2.07cm non-enhancing cystic lesion in the region of the pineal gland compressing the tectum and narrowing the cerebral aqueduct (Figure 4).

|

| Fig. 2. Results of 30-2 Humphrey visual fields at the initial visit were within normal limits. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

In clinical practice, we often favor more common differential diagnoses over those that are more rare as we consider disease process etiologies. Given our patient’s age, gender and BMI, we should consider idiopathic intracranial hypertension as a leading diagnosis. This case demonstrates the need to entertain more rare differentials, even though they may seem unlikely.

Papilledema, by definition, results from elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). Space-occupying lesions, increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume due to overproduction or decreased drainage, decreased skull volume and idiopathic causes may all result in elevated ICP. Symptoms of elevated ICP are not specific to etiology but may include headaches, nausea, vomiting, pulse-synchronous tinnitus, blurred vision, transient visual obscurations, diplopia and lethargy. Less commonly, behavioral changes, memory loss, gait disturbance, respiratory depression, bradycardia and bladder incontinence may also be observed.

Hydrocephalus is a condition hallmarked by enlarged ventricles in the setting of clinical signs or symptoms of increased ICP. Globally, the prevalence of hydrocephalus in the pediatric population (0 to 18 years) is 71.9 per 100,000 patients.1 Adults (19 to 64 years) appear to have the lowest prevalence at 10.9 per 100,000 patients, and the highest prevalence has been reported in those older than 65 at 174.8 per 100,000 patients.1 The prevalence of hydrocephalus varies greatly based on geography, and the etiology differs by age.1

|

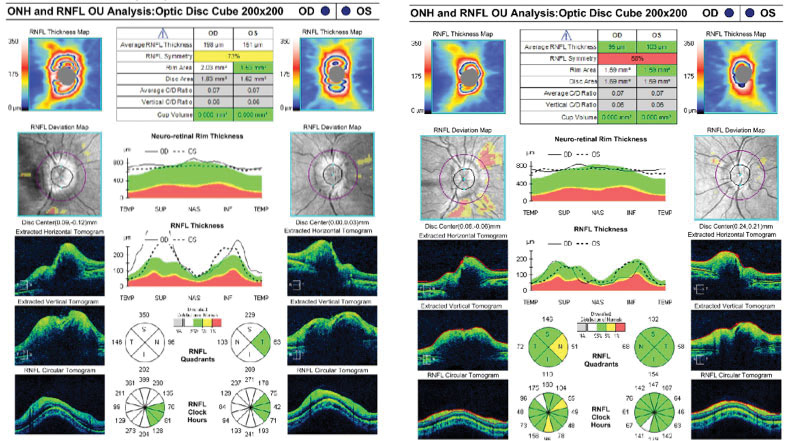

| Fig. 3. OCT retinal nerve fiber layer analysis at the initial visit revealed slightly increased values, suggesting possible disc edema. Click image to enlarge. |

When a physical blockage is present in CSF passages or ventricles, it is termed obstructive hydrocephalus. Neuroimaging is critical to visualize enlarged ventricles and determine the nature of the blockage, whether secondary to tumor, hemorrhage, infection or congenital defect. Though treatment is individualized and highly dependent on the etiology, shunt systems and endoscopic ventriculostomy are generally the two preferred procedures. In cases with a space-occupying mass, tumor resection may be done as a stand-alone treatment or in tandem with another procedure.

Based on our results, we diagnosed the patient with obstructive hydrocephalus secondary to a large pineal gland cyst. The pineal gland is a small neuroendocrine organ averaging 7.4mm in length by 2.4mm in height.3 It is located behind the third ventricle and helps regulate the body’s biological reaction to light and dark through the production of melatonin. One study states there is an incidence of pineal cysts in approximately 1% to 4% of individuals undergoing MRI.4 The prevalence is higher in females, and these cysts occur most commonly during the second decade of life.4

Benign pineal gland cysts are typically less than 1cm in diameter, but their anatomical position may allow for compression of the third ventricle and obstruction of CSF flow if large enough, as seen in our patient.4

|

|

| Fig. 4. MRI revealed a large pineal cyst (blue circles). Click images to enlarge. |

Treatment

Once the patient was educated on her condition, she became more amenable to further evaluation and treatment. Despite the likely long-standing nature of her diagnosis, the impetus was on us to ensure urgent follow-up with neurology. We discussed the case with the on-call neurosurgery team, and they agreed to see our patient the following day.

Four days after her initial presentation, the patient underwent a complete resection of the lesion via suboccipital craniotomy. Pathology revealed it was a benign pineal cyst. About two weeks after surgery, a refractive evaluation and comprehensive exam endorsed stable vision with very mild headaches but worse optic nerve edema (Figure 5a). No further intervention was deemed necessary at that point, and she was monitored carefully.

At the patient’s two-month follow-up, her headaches had resolved and optic nerve edema had significantly improved (Figure 5b). She was instructed to continue follow-up with routine ophthalmic visits to monitor her optic nerve function and ocular hypertension.

|

| Figs. 5a & 5b. RNFL scans at two weeks (left) and two months (right) post-surgery revealed initial worsening and subsequent improvement of disc edema. Click image to enlarge. |

To Sum Up

This case highlights the importance of maintaining a broad differential during your evaluation no matter how rare the potential diagnosis. Despite the initial delay in diagnosis due to poor follow-up, our patient ultimately did well and experienced resolution of her symptoms.

Dr. Bozung works in the Ophthalmic Emergency Department of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami and serves as the clinical site director of the Optometric Student Externship Program. She has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Mangan is a board-certified consultative optometrist from Boulder, CO, and a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. He is an assistant professor in the department of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. His focus is on ocular disease and surgical comanagement. He has no financial interests to disclose.

| 1. Isaacs AM, Riva-Cambrin J, Yavin D, et al. Age-specific global epidemiology of hydrocephalus:sSystematic review, metanalysis and global birth surveillance. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204926. 2. Jiang L, Gao G, Zhou Y. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy and ventriculoperitoneal shunt for patients with noncommunicating hydrocephalus: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(42):e12139. 3. In: Turgut M, Kumar R, Steinbok P, eds. The Pineal Gland and Melatonin: Recent Advances in Development, Imaging, Disease and Treatment. Nova Science Publishers; 2011. 4. Starke RM, Cappuzzo JM, Erickson NJ, et al. Pineal cysts and other pineal region malignancies: determining factors predictive of hydrocephalus and malignancy. J Neurosurg. 2017;127(2):249-54. |