|

A 35-year-old mentally handicapped Hispanic male presented with his mother for a second opinion on possible treatment options to help him see better. He reported a gradual painless, progressive loss of vision in both eyes that started at about nine years old. His mother reported that his vision was so poor by age 14 that he was only able to detect light.

His medical history is significant for mental delay. He also has hearing loss and polycystic kidney disease. As a child, he had strabismus surgery on the right eye to improve alignment and also had surgery to remove extra toes.

On examination, he had only light perception vision in each eye. Though his extraocular alignment appeared normal, he did have roving eye movements. His pupils were equal, round and reactive to light; there was no afferent pupillary defect. Tensions by applanation tonometry measured 12mm Hg in each eye. The anterior segment was unremarkable.

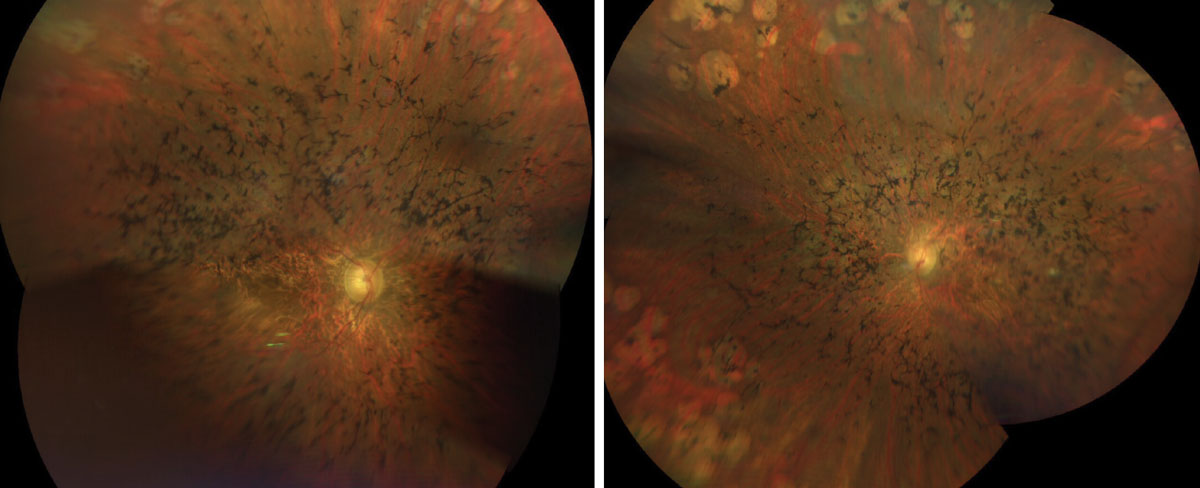

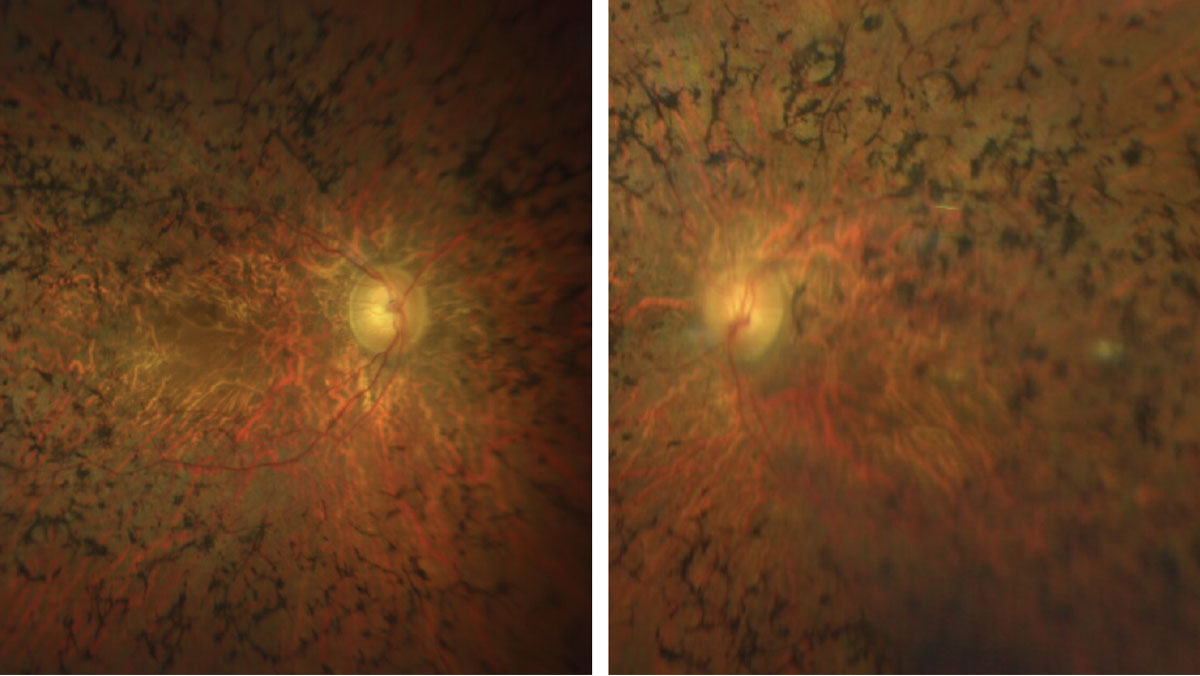

Dilated fundus exam was significant for vitreous syneresis and a posterior vitreous detachment in each eye. Other changes can be seen in Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4.

|

Figs. 1 & 2. Here is a widefield view of the right and left eye of our patient. How do you explain the clinical findings? Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. Which of the following best describes the OCT of the right eye?

a. Fundus albipunctatus.

b. Retinitis pigmentosa.

c. Stargardt's macular disease.

d. Gyrate atrophy.

2. What is the likely etiology?

a. Bardet-Biedl syndrome.

b. Defect in ABC4 gene.

c. Usher's syndrome.

d. Non-specific hereditary retinal degeneration.

3. What other systemic findings would you expect to see in this patient?

a. Tall, thin stature.

b. Cardiac abnormalities.

c. Testicular hypogonadism.

d. Normal development.

4. What treatment options should be considered for this patient?

a. Stem cell implantation.

b. Genetic therapy.

c. Argus retinal implant.

d. All of the above.

For answers, see below.

Diagnosis

Sadly, our patient has advanced retinitis pigmentosa (RP). There is extensive bone pigment spicules throughout the arcades and extending into the posterior pole. The vessels are severely attenuated and there is some pallor of the optic nerve, but not as much as you would expect considering how advanced his disease is.

RP is a genetically heterogeneous group of disorders with varying modes of inheritance from autosomal dominant to x-linked recessive. Patients will develop bilateral, progressive vision loss, typically between the ages of nine and 19 with no sex or race predilection.1 Symptoms include night blindness (most common), loss of peripheral vision, reduced color vision and blurred vision.2-3 Signs include the triad of perivascular bone-spicule pigmentation in the mid-periphery, waxy pallor of the optic disc and vessel attenuation. Other findings commonly seen in RP include cystoid macular edema, diffuse RPE atrophy, optic disc drusen (10%), epiretinal membrane, vitreous condensation, keratoconus and posterior subcapsular cataracts (35% to 51% of cases).2

|

Figs. 3 & 4. Here is a closer view of the macula and posterior pole of our patient. How would you characterize the optic nerves? Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

An estimated 100,000 people in the United States have RP and more than 80 mutated genes are known to cause this condition.4-6 In fact, RP may represent many different genetic disorders leading to a final common pathway that is clinically recognized as RP. The vast majority of cases affect only the eyes; however, there are several systemic conditions that are associated with RP, including Usher’s syndrome and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS), among others. It is evident based on our patient’s medical history and clinical findings that he has BBS.

BBS is a genetic condition that impacts multiple body systems. It is classically defined by six features: obesity (specifically, fat deposition along the abdomen), intellectual impairments, kidney problems, genital and hormonal problems (hypogonadism), extra toes and digits (polydactylism) and visual impairment in the form of a rod-cone dystrophy, which occurs in 90% of patients with BBS.7 This condition develops as the result of mutations in more than 21 different genes and is usually autosomal recessive. Of the 21 genes, the most common are BBS1 (28% of cases), BBS10 (10% of cases), BBS2, BBS12 and ARL.6,7

Interestingly, there is no clear link between the different mutations identified and disease severity, but some trends have emerged. Patients with mutations in the BBS1 gene seem to have milder ophthalmologic involvement, whereas patients with mutations in the BBS2, BBS3 and BBS4 genes experience classic deterioration in their vision. Our patient had all the classic features of BBS including, unfortunately, severe RP.8

There is no specific cure for RP. For blind individuals with this condition, the Argus II Retinal Prosthesis System is considered with the hopes of providing useful vision to those that are severely impacted. The device combines a miniature eye implant with a patient-worn camera and a processor; it stimulates the visual cortex to sense shimmering, light or dark patterns or spots. The patient must learn how to interpret these signals as shapes and objects. The vision generated by Argus II is very different from traditional sight and the patient learns to interpret the new “language” of sight.9

Unfortunately, our patient was not a candidate for the Argus II because of his roving eye movements and mental delay. In these types of situations, we make sure visually handicapped patients are referred to the Miami Lighthouse for the Blind, but our patient was already well-connected. In fact, he had been using a mobile cane for close to 20 years. He travels by himself to places such as the Lighthouse, the gym and the mall while using public transportation, and he is fluent in Braille.

Retina Quiz Answers

1: b; 2: a; 3: c, 4; c

Dr. Dunbar is the director of optometric services and optometry residency supervisor at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami. He is a founding member of the Optometric Glaucoma Society and the Optometric Retina Society. Dr. Dunbar is a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditec, Allergan, Regeneron and Genentech.

| 1. Fahim AT, Daiger SP, Weleber, RG. Nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa overview. Gene Reviews. January 19, 2017. 2. Hamel C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:40. 3. Iannaccone A, Berdia, J. Retinitis Pigmentosa. National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/retinitis-pigmentosa. July 5, 2016. Accessed March 17, 2022. 4. Birtel J, Gliem M, Mangold E, et al. Next-generation sequencing identifies unexpected genotype-phenotype correlations in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207958. 5. Ge Z, Bowles K, Goetz K, et al. NGS-based molecular diagnosis of 105 eyeGENE probands with retinitis pigmentosa. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18287. 6. Haer-Wigman L, van Zelst-Stams WA, Pfundt R, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in 266 Dutch patients with visual impairment. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25(5):591-9. 7. Bardet-Biedl Syndrome (BBS): for patients. Gene Vision. www.gene.vision/knowledge-base/bardet-biedl-syndrome-bbs-for-patients/#cite_note-1. November 30, 2020. Accessed March 17, 2022. 8. Bardet Biedl Syndrome. National Organization of Rare Disease Database (NORD). www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/bardet-biedl-syndrome. Accessed March 17, 2022. 9. Discover Argus II. Second Sight. www.secondsight.com/discover-argus. 2019. Accessed March 17, 2022. |