|

A 62-year-old Caucasian male presented to our office with concerns about his changing vision. Years before, he had a melanoma in his right eye, which was irradiated and treated with plaque therapy. He noted gradually changing vision in both eyes, and that prompted him to see another optometrist in the area earlier, but that doctor said that he “had too many things going on” and referred the case to a glaucoma surgeon. The patient found his way to me first, and it’s a good thing he did because, despite the many factors complicating his glaucoma, he wasn’t yet a surgical patient—so why send him to a surgeon?

He only reported using a statin for management of hypercholesterolemia. He reported no allergies to medications.

Examination

His best-corrected visual acuities were 20/400 OD and 20/40+ OS. His intraocular pressure (IOP) readings were 24mm Hg OD and 23mm Hg OS. Pachymetry measurements were 501µm OD and 507µm OS.

Through dilated pupils, his crystalline lenses were clear in both eyes. A large macular scar was visible in his right eye, most likely consistent with the post-radiation plaque years ago. The macula in the left was characterized by a moderate epiretinal membrane (ERM).

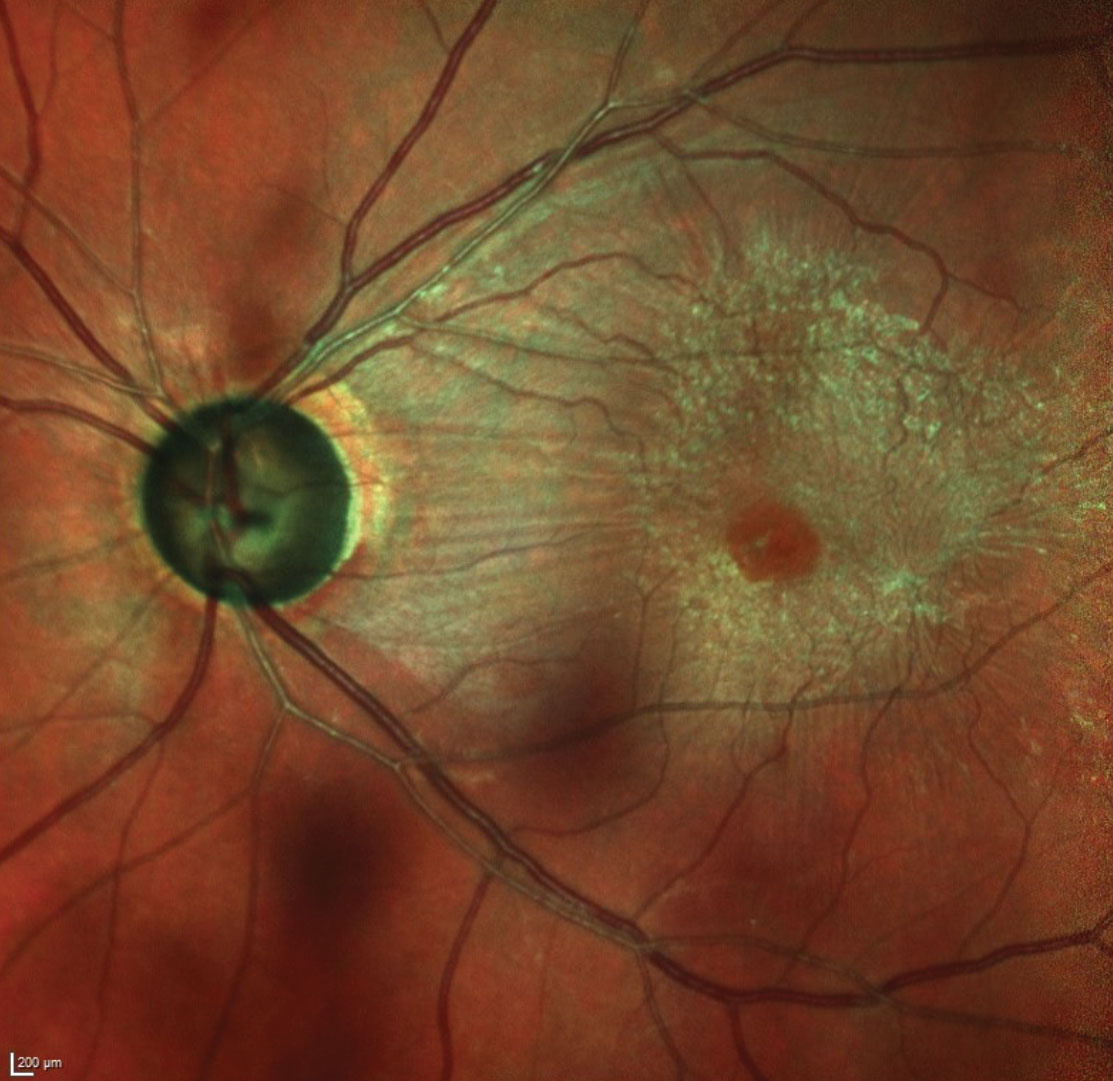

The optic nerve evaluations were consistent with moderately advanced glaucomatous damage in the right and left eyes, with very thin neuroretinal rims in both eyes. The retinal vasculature was characterized by moderate arteriolarsclerotic retinopathy OU. His peripheral retinal evaluations were unremarkable. Optic nerve multicolor images were obtained at the initial visit.

|

| This multicolor image of the left optic nerve and macula shows the patient’s thinned neuroretinal rim as well as the moderate ERM. Also, note the wedge defect inferotemporally. Other wedge defects, if present, were obscured by the ERM. Click image to enlarge. |

Making a Diagnosis

Clearly, he had glaucoma bilaterally. He was subsequently scheduled for several follow-up visits to ascertain the level of damage and stabilize the situation. He was compliant with his visits. His average IOPs over three pretreatment visits were 22mm Hg OD and OS.

Visual fields showed moderate loss in his left eye related to the glaucoma, with field defects encroaching on fixation; the field in the right was uninterpretable, as he was unable to fixate due to the macular scarring.

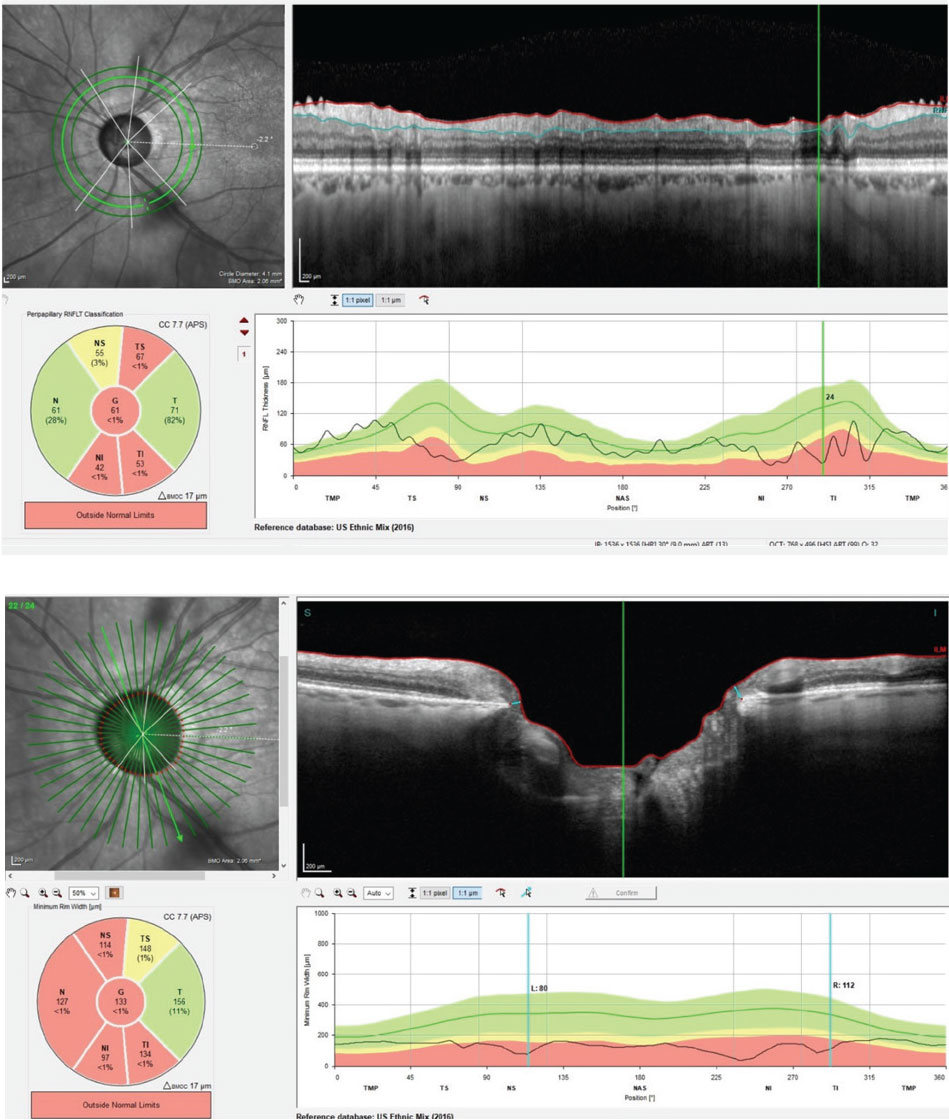

OCT evaluation of both eyes demonstrated advanced damage as seen on the Bruch’s membrane opening-minimum rim width (BMO-RMW) neuroretinal rim scans, as well as moderate damage in the circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL).

A trial of Xelpros (latanoprost, Sun Pharmaceuticals) was initiated, and on four subsequent follow-up visits, post-treatment IOPs had averages of 13mm Hg OD and 12mm Hg OS. He continues using drops and his glaucoma is currently stabilized.

Finding the Right Optometrist

The lesson here is one of case management. In the initial encounter, the patient mentioned that the previous doctor claimed he “had too many things going on” and that he needed to see a surgeon. I didn’t probe as to what the “things” were, but I have a pretty good guess. The patient was, essentially, visually monocular (insofar as acuity was concerned). He had advanced cupping OU. He had a moderate ERM in his better-seeing left eye. Because of these things, I assume, he was told he needed to see a surgeon.

The term “DNR” usually stands for the medical directive do not resuscitate. However, I used the term to describe a trend I’m seeing that worries me: detect ‘n’ refer. I am fully aware that many ODs do not manage glaucoma at all. That is perfectly OK, as I don’t practice all aspects of optometry. I don’t see pediatric cases, I don’t fit specialty contact lenses, I don’t do vision therapy. However, I know ODs who do take on these types of cases.

I often hear of situations like this one, where a patient is referred out to a “specialist.” This patient needed glaucoma management. In 49 states, that’s within optometry’s domain. If you don’t treat glaucoma yourself, why not send your patient to another optometrist?

|

| At top, this circumpapillary RNFL scan of the patient’s left eye demonstrates significant loss in the superiotemporal and inferiotemporal sectors of the scan. Below, the same eye’s BMO-MRW scans demonstrates advanced neuroretinal rim loss and thinning. Both scans are consistent with moderately advanced glaucoma. Click image to enlarge. |

If You Treat, Keep Treating

Even those who do treat glaucoma can be guilty of detecting and referring. I’ve heard cases where the patient is referred to a surgeon because they didn’t respond to the initial treatment, or the drop reddened their eyes or for fear of liability. Certain cases ultimately will need to go to a glaucoma specialist for surgical management, yes, but the large majority of glaucoma cases do not need surgical intervention. In other words, non-surgical glaucoma care is optometric glaucoma care. These patients, even advanced cases, are in our wheelhouse! We can’t cherry-pick the cases we see. If we’re going to treat glaucoma, then we need to treat the difficult cases as well as the easy ones.

I’m sure a letter to the editor will follow from this analogy, but how many ODs have an upper limit of refractions that they will do? Do ODs cut off and refer out patients with refractive errors over a certain myopic level? My guess is not. Though the higher myope may carry more risk, it’s certainly the practice of optometry to see them and not refer them for refractive care because they are “too myopic.” The same holds true for glaucoma.

Sure, some glaucoma does get worse, despite the best therapeutic decisions. But that happens to ophthalmology as well. Fix it. Adjust the medications. Try different therapies. If things are still not stable, then an upstream referral is necessary. Why stop at one drop? Why refer out if the eye is red when that issue could be solved with a different drop? Why worry when a long-standing glaucoma patient worsens? That’s what diseases do. Adjust. Recalculate. Rethink management. You can do this. We all can do this.

These are challenging times. Optometrists feel the pressure from all sides. Decreased reimbursements. Increased government intrusion. Patients who are less than pleasant. Coronavirus. It might seem harder to sustain a practice than ever these days. But, there will always be patients with sick eyes who need you. In fact, there may be more than ever. Those sick eyes can sustain a practice very nicely.

If you’re going to DNR, at least refer to an optometrist who works in that field. If your practice doesn’t allow you to manage diseases, an OD near you likely can do it. And if you are in a practice where you state that you ‘treat ocular disease’, but Detect ‘N’ Refer most of those patients out your door, you’ve figuratively put a sign with that other DNR on your practice’s door: Do not resuscitate this practice, for it is on its way out.