The conjunctiva is a thin mucus membrane whose primary functions are to provide barrier protection, immunity and lubrication to the ocular surface. There are three distinct anatomical locations of conjunctival tissue: the palpebral, the bulbar and the forniceal. The conjunctiva itself is made up of the epithelium and the stroma (also known as the substantia propria). The epithelium is a few cell layers thick and consists of various cell types. Stratified cuboidal cells are found over the tarsus, columnar cells are found in the fornices and squamous cells are found on the bulbar conjunctiva.1 The stroma is made up of loose, vascularized connective tissue rich in elastic fibers. This gives the conjunctiva the ability to flex and stretch upon blinking and eye movement.2 The stroma is also rich in lymphocytes and plays an important role in the immunologic response of the ocular surface.

|

|

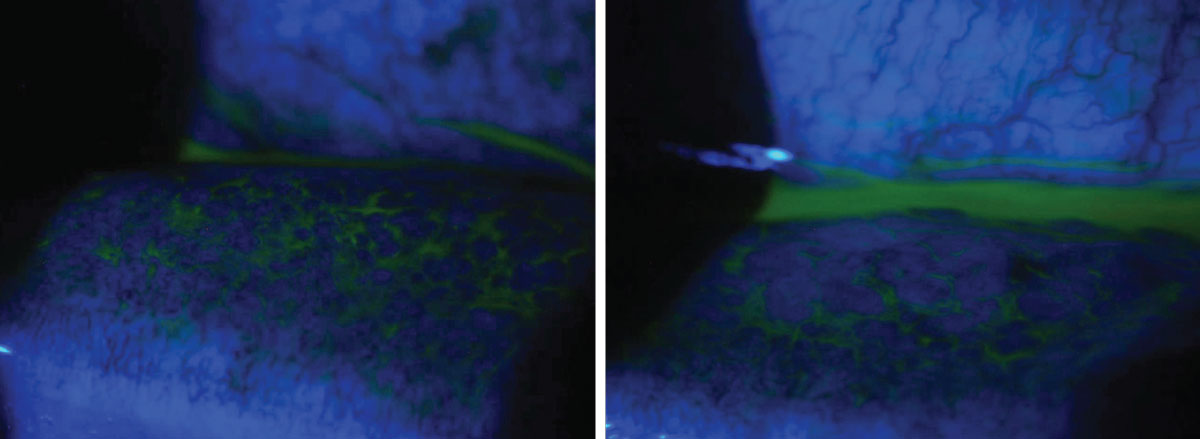

A 58-year-old male presented with complaints of irritation in the left eye. He saw another provider the day prior and was given moxifloxacin. He started using the drops but felt this made his symptoms worse, and the pain and redness moved to both eyes. He reported tearing and mild crusting of his lids in the morning. On examination, both eyes revealed 2+ conjunctival injection and a 2+ follicular response. The patient was diagnosed with viral conjunctivitis and educated on the contagious nature and expected duration of the condition. He was instructed to discontinue the topical antibiotic, wash all towels and sheets and use preservative-free artificial tears four times daily in both eyes. Despite the controversy over steroids in viral disease in the absence of corneal involvement, the patient was placed on a sample of Eysuvis (loteprednol etabonate, Kala Pharmaceuticals) four times daily in both eyes due to the degree of discomfort and his ability to take time off work. He was instructed to return in two weeks for follow-up with an IOP check and to call with any worsening of symptoms. Click image to enlarge. |

The conjunctiva is dense in mucin-producing glands including goblet cells, Crypts of Henle and glands of Manz. Goblet cells are located in the conjunctival epithelium, Crypts of Henle are located in the palpebral conjunctiva and glands of Manz are located near the limbus. The mucin layer is the innermost layer of the tear film and is made up of glycoproteins. On the ocular surface, hydrophilic mucins are responsible for adherence of the tear film to the ocular surface, decreasing surface tension and ensuring the overlying aqueous can spread evenly across the front of the eye. This is critical for protecting the conjunctival and corneal epithelium by preventing dryness, clearing debris and fending off pathogens.3

The accessory lacrimal glands of Krause and Wolfring can also be found in the conjunctiva. They are located in the fornices and the tarsus, respectively. These glands produce aqueous secretions to supplement the lacrimal gland.4 The accessory lacrimal glands do not contain parasympathetic innervation and are thought to be responsible only for basal secretions.5

Now that we have reviewed the anatomy, let’s take a closer look at how several common conjunctival conditions manifest clinically. Understanding the innerworkings of this ocular structure will help you differentiate and diagnose the following:

Acute Conjunctivitis

Conjunctival inflammation is marked by a variety of signs including injection, chemosis and discharge. Accurate discrimination of the causes of inflammation is important to direct appropriate treatment, patient education and follow-up. An important differentiation in conjunctivitis is a follicular vs. papillary response. Follicles are aggregations of lymphoid tissue and appear as gray/white dome-like elevations with a small surrounding blood vessel. They are formed within the conjunctival stroma. Follicular conjunctivitis is associated with acute viral and chronic chlamydial infections, Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome and hypersensitivity to topical ophthalmic medications.4

Papillae, in contrast, contain a central vessel making the elevated tissue red in color. They are formed by the hyperplastic conjunctival epithelium. Papillary conjunctivitis is indicative of allergic or bacterial conjunctivitis, chronic blepharitis, contact lens–associated reactions and floppy eyelid syndrome.4

Viral. This form of conjunctivitis is the most common type of infectious conjunctivitis. It often starts in one eye and moves to the other within a few days. The most common pathogen is adenovirus. A four- to 10-day incubation period is typical of adenoviral conjunctivitis.4 The virus can continue to shed for approximately 12 days.4

The most common types of adenoviral conjunctivitis are pharyngoconjunctival fever (PCF) and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC), both of which are highly contagious. PCF is more prominent in children and is often accompanied by a recent upper respiratory infection and a low-grade fever. It is predominantly caused by adenovirus serotypes three, four and seven.4 EKC is often caused by hand-eye contact. There are typically no concurrent systemic symptoms. EKC is caused by adenovirus serotypes eight and 19.4

Viral conjunctivitis typically presents with watery discharge, injection, follicles and lid edema. Patients often report discomfort and photophobia. In severe cases, subconjunctival hemorrhages, chemosis and pseudomembranes can manifest. The preauricular or submandibular lymph nodes are often swollen as well. In EKC, punctate epithelial erosions are observed from days seven to 10. Later, subepithelial infiltrates present, followed by anterior stromal infiltrates.

Pseudomembranes can occur in severe adenoviral conjunctivitis or gonococcal conjunctivitis. They can develop on the upper and lower palpebral conjunctiva and fornices. Pseudomembranes consist of exudates that have gently adhered to the conjunctival epithelium, which should be peeled off with a damp cotton swab or forceps to avoid disrupting the conjunctival epithelium.4 True membranes, in contrast, involve the conjunctival epithelium. Removal of a true membrane often causes bleeding and scarring. They contain white blood cells, fibrin and necrotic debris that firmly adheres to epithelial cells.6 Common causes of true conjunctival membranes include Streptococcus pyogenes and Corynebacterium diphtheria.4

|

|

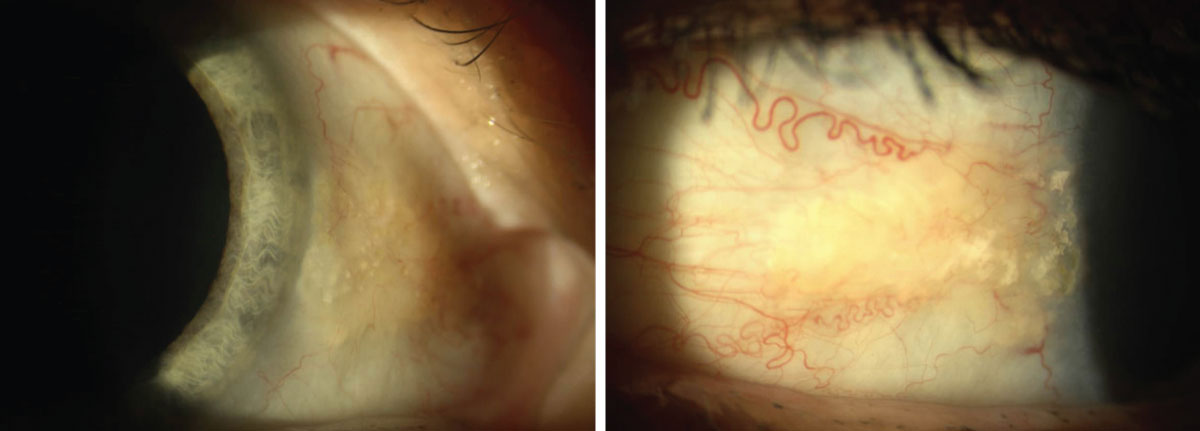

Asymptomatic nasal and temporal pingueculae in a 60-year-old Caucasian female. Click image to enlarge. |

Testing for adenoviral conjunctivitis can be performed in-office with a QuickVue Adenoviral Conjunctivitis Test (Quidel), formerly known as the RPS Adenoplus. It has a high sensitivity (85% to 90%) and specificity (96% to 98%) when compared with cell culture and polymerase chain reaction, more cumbersome diagnostic alternatives.7 It is best used on the more inflamed eye within seven days of onset and takes 10 minutes to deliver results.

Treatment is largely supportive and includes both cool compresses and artificial tears to provide symptomatic relief. Resolution usually occurs within 14 days. Antibiotics should be avoided in viral conjunctivitis, and steroids should be used judiciously in cases of corneal infiltrates or severe inflammation only. Topical steroids can provide symptomatic relief, but they can also cause increased viral shedding and longer duration of disease.8-10 This means the patient may remain contagious for a longer period of time. Patients should be advised to frequently wash their hands, avoid touching their eyes and wash their towels and sheets. They are considered contagious as long as their eyes are still producing watery discharge.

The off-label use of betadine 5% is also a highly effective means of reducing the viral load, especially in earlier stages of disease. Betadine shortens the infectious period and reduces the risk of subepithelial infiltrates in EKC.11 The recommended procedure is to instill a topical anesthetic followed by a topical NSAID, then four to five drops of betadine. Have the patient gently close their lids and move their eyes around for 30 to 60 seconds. Then irrigate the eyes thoroughly with saline. Once irrigation is complete, instill another NSAID and prescribe Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension or gel, Bausch + Lomb) four times daily for four to five days. Lotemax aids in both comfort and improvement of the ocular surface following the betadine flush. Follow-up is recommended within a few days to ensure improvement in clinical signs and symptoms.11

|

|

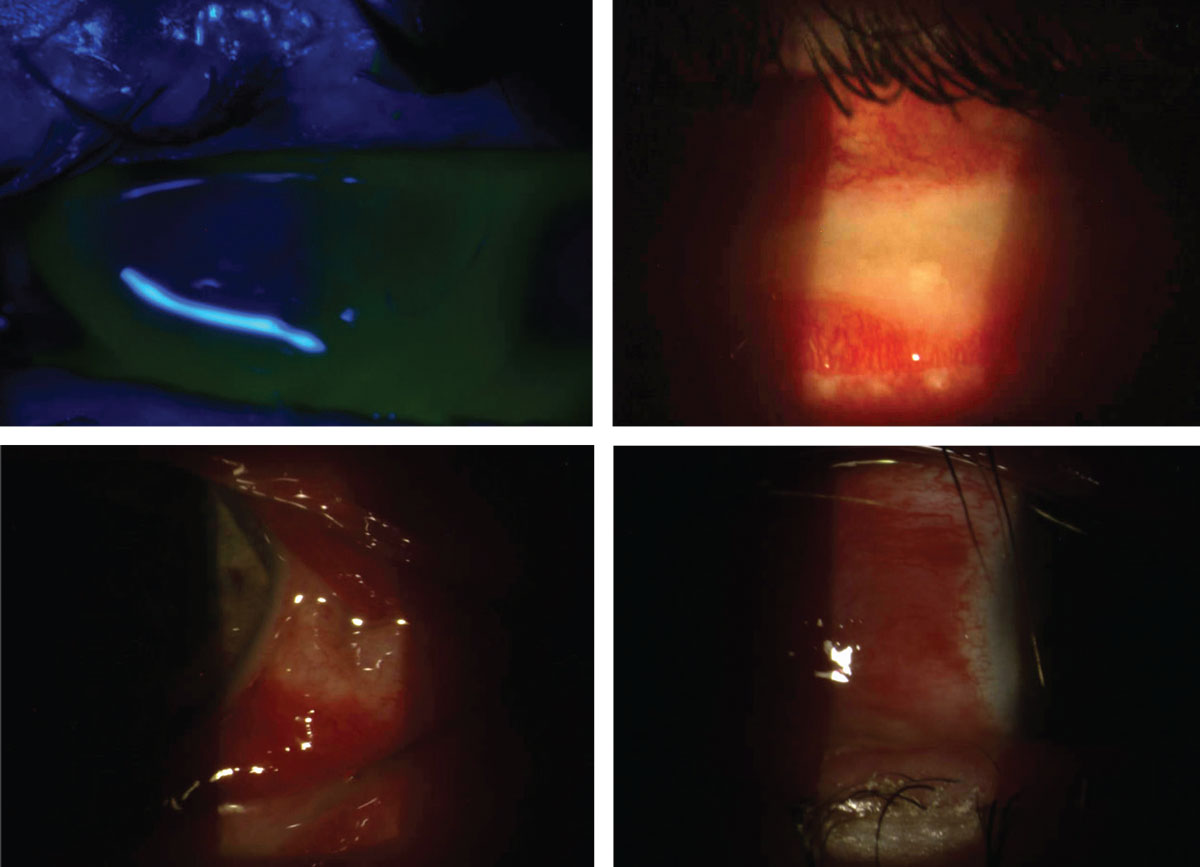

Severe mucopurulent bacterial conjunctivitis with significant lid swelling, ecchymosis, conjunctival injection and chemosis in a 30-year-old Caucasian male. Symptoms had started four days prior and seemed to be worsening daily. The patient was referred from his primary care provider. He denied any history of contact lens wear or trauma. The patient had a positive history for unprotected intercourse with a new partner two days prior to the onset of symptoms, but neither had genitourinary symptoms and his female partner had no ocular symptoms. Based on the severity of discharge, gonococcal conjunctivitis was suspected. The discharge was cultured, and the patient was sent for a 1g IM injection of ceftriaxone and placed on moxifloxacin hourly. He was instructed to keep the lids as clean as possible and regularly flush out the discharge with saline. He was followed daily to monitor for corneal involvement. Ultimately, testing came back negative for gonococcal disease, chlamydia and syphilis. With this negative result, an especially severe Staph. or Strep. infection was suspected. Click image to enlarge. |

Bacterial. This next form of conjunctivitis most commonly affects children but can also occur in adults. It results from infiltration of the conjunctival epithelium and occasionally stroma. The most common pathogens are Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Look for papillae, redness and purulent discharge. It is important to rule out corneal involvement in these cases. Patients may complain of burning, a gritty sensation and their lids sticking together, especially in the morning.

Bacterial conjunctivitis is often self-limiting, resolving within 10 to 14 days, especially in milder forms of disease. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, however, can alleviate symptoms, shorten duration of the condition and reduce the risk of recurrence.12,13 Antibiotics should also be strongly considered in contact lens wearers due to the risk for corneal involvement and a higher prevalence of gram-negative pathogens. Contact lens wear should be discontinued until symptoms have ceased. Patients should resume wear when appropriate with a new set of contact lenses and a new case. Instruct patients to keep their lids and lashes clean and clear of discharge.

Acceptable broad-spectrum options include Polytrim (polymyxin B and trimethoprim, Allergan), Azasite (azithromycin, Akorn), erythromycin ointment and fluoroquinolones.14 Polymyxin B and trimethoprim, erythromycin and fluoroquinolones are dosed four times daily, while azithromycin is dosed twice daily for five to seven days. Patients should respond to treatment within 24 to 48 hours. Although later-generation fluoroquinolones are highly effective agents at treating a variety of bacterial strains, alternative antibiotics should be considered for routine bacterial conjunctivitis. Avoiding antibiotic resistance is critical, as fourth-generation fluoroquinolones are the first line of treatment for corneal ulcers and severe bacterial conjunctivitis and must remain efficacious in treating more sight-threatening infections.

Hyperacute bacterial conjunctivitis should be cultured and treated rapidly. This condition is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and appears with severe mucopurulent discharge within 12 hours of exposure. Concurrent genitourinary symptoms are common. Patients with suspected gonococcal conjunctivitis should be asked about their recent sexual history and possible source of exposure.

|

|

True conjunctival membranes and residual conjunctival scarring in the same 30-year-old Caucasian male in the previous set of photos with severe bilateral bacterial conjunctivitis. The membranes were confirmed when a damp cotton swab was unsuccessful in removal. Once discharge subsided and the ocular surface was considered sterile, the patient was treated with aggressive topical steroids to minimize conjunctival scarring and resolve corneal infiltrates. Click image to enlarge. |

The recommended treatment is 1g of intramuscular ceftriaxone and a topical fluoroquinolone.15 These patients should be monitored daily, as Neisseria gonorrhoeae can penetrate an intact cornea. Generally, culturing is not required in acute infectious conjunctivitis, but it is warranted in suspected gonococcal disease due to the risk of rapid corneal ulceration and its unique treatment. Neisseria gonorrhoeae has developed resistance to many antibiotic classes, and culturing allows testing for antibiotic susceptibility. In patients where a concurrent infection of chlamydia has not been ruled out, a seven-day course of 100mg doxycycline twice daily is also recommended.15

Allergic. This type of conjunctivitis is a bilateral condition marked by ocular itching. Other symptoms may include tearing, burning and foreign body sensation. Upon examination, eyelid edema, conjunctival hyperemia, papillae and ropy white discharge may also be observed. A careful case history is important to determine the causative agent(s).

Allergic conjunctivitis encompasses acute, seasonal and perennial conjunctivitis. It is a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction. In this condition, circulating allergens trigger the release of IgE and go on to stimulate mast cell production and histamine release. Mast cells are present in high concentrations in the conjunctival epithelium in these patients.16 Allergic conjunctivitis is more prominent in young adults, as symptoms tend to improve with age, and eczema is a common concurrent condition in these patients.17

First-line treatment includes topical antihistamines or a combination of antihistamine and mast cell stabilizers. Over-the-counter combination options include Pataday (olopatadine, Alcon), Zaditor (ketotifen, Alcon) and Alaway (ketotifen, Bausch + Lomb), the latter of which is now available in a preservative-free formulation. Solo topical antihistamine options include Bepreve (bepotastine besilate, Bausch + Lomb), Lastacaft (alcaftadine, Allergan) and Zerviate (cetirizine, Eyevance Pharmaceuticals). All three of these formulations are available by prescription only.

Oral antihistamines can also be considered, especially when nasal symptoms accompany ocular symptoms. These are best used preventatively. Another supplemental option is a topical mast cell stabilizer such as Crolom (cromolyn sodium, Bausch + Lomb). Cool compresses and artificial tears can provide adjunctive symptomatic relief. In more severe forms of allergic conjunctivitis, soft steroids can be considered such as Alrex (loteprednol etabonate, Bausch + Lomb), which is FDA-approved for allergic conjunctivitis, Lotemax (loteprednol, Bausch + Lomb) and FML (fluorometholone, Allergan). It is also important to educate patients to avoid eye rubbing and known allergens.

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a more severe form of allergic conjunctivitis and can be sight-threatening. It is a recurrent, bilateral condition marked by cobblestone papillae on the upper palpebral conjunctiva. It is more common in young males in dry, warm climates. Patients suffering from VKC will experience severe itching, increased blink rates and mucus discharge. VKC is both IgE- and cell-mediated and is marked by significant eosinophil, mast cell and fibroblast release. It resembles both type one, IgE-mediated and type four, delayed hypersensitivity reactions.18,19 Patients should be monitored carefully for limbal and corneal involvement. Treatment is very similar to that of allergic conjunctivitis. Combination antihistamine and mast cell stabilizers should be considered first-line therapy, but topical steroids may be required in more significant disease.4

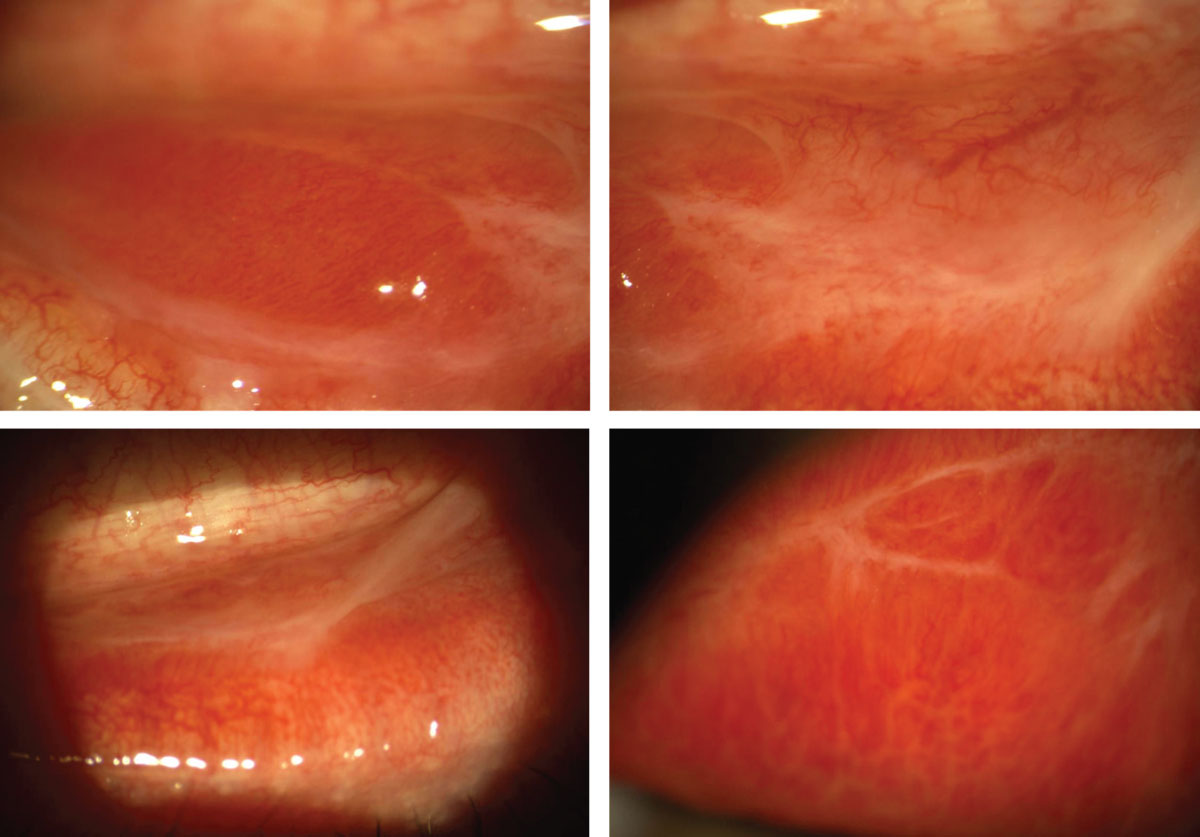

Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis (GPC)

This non-allergic condition occurs secondary to mechanical rubbing on the tarsal conjunctiva and an immune-mediated inflammatory response. Although not fully understood, it also exhibits features of both type one and type four hypersensitivity reactions.20 GPC most commonly occurs due to contact lens wear but can also be stimulated by exposed sutures, filtering blebs, ocular prostheses and scleral buckles. When induced by contact lenses, symptoms tend to be worse following lens removal. Patients will often report foreign body sensation, itching, redness and increased mucus discharge. The condition is marked by redness and papillae of the superior palpebral conjunctiva. Protein deposition is also commonly found on contact lenses in lens-induced GPC.

The first line of treatment is to remove the irritant for a couple of weeks. For lens-induced GPC, the patient should switch to a different contact lens material or to daily disposable contact lenses when wear is resumed. Patients should also be discouraged from overwearing their lenses. Topical steroids can be utilized to treat inflammation. In cases where daily disposables are not a viable alternative, it is important to ensure proper cleaning of contact lenses. Thorough disinfection is also imperative in cases of GPC induced by an ocular prosthesis. An ocularist can be consulted in these instances.

Conjunctivochalasis

This condition is evident by redundant conjunctival tissue which occurs most commonly with increasing age as elastic fibers are lost.21 Ocular rubbing, mechanical forces, trauma and previous surgeries can also increase the risk of conjunctivochalasis development.21,22 It most commonly occurs in the infratemporal quadrant of the bulbar conjunctiva. Although frequently asymptomatic, symptoms such as ocular surface discomfort, epiphora and dryness can occur. Conjunctivochalasis blocks normal tear movement and disrupts the tear meniscus.23,24 Symptoms often worsen with downgaze and with an increased blink rate.25 Conjunctivochalasis is frequently under-diagnosed as a source of ocular discomfort.

|

|

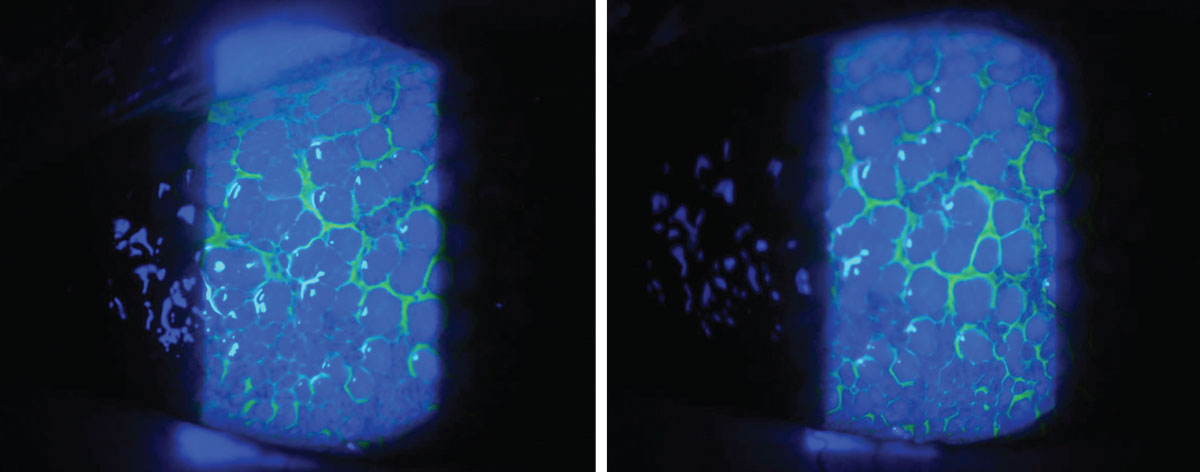

A 59-year-old Caucasian female presented with irritation and foreign body sensation in the left eye greater than the right for the last few days. She reported sleeping in her two-week disposable contact lenses prior to the onset of irritation. Examination revealed GPC in the left eye greater than the right. The patient was instructed to discontinue contact lens wear for two weeks and placed on Tobradex (tobramycin and dexamethasone, Novartis) QID for one week. Based on her high-risk contact lens history, mild crusting of the lid margin and mild corneal edema in the left eye on examination, an antibiotic-steroid combination was selected. The patient was instructed to return in two weeks for follow-up, at which point she was switched to a daily disposable contact lens modality. She responded well to therapy. Click image to enlarge. |

In asymptomatic patients, no treatment is required. In cases of mild discomfort, frequent artificial tears can be utilized. This helps to ensure that an adequate supply of tears is spread across the ocular surface despite a disrupted tear meniscus. If the redundant conjunctiva is exposed overnight, consider lubricating ointment or patching. A short, soft topical steroid course is the next line of treatment if supportive therapy is unsuccessful. This is especially helpful in cases of increased inflammation. Cyclosporine may also be beneficial based on its inhibitory effect on inflammatory cytokines, which are often found in the tear film of those with conjunctivochalasis. In patients with more severe symptoms, the chalasis can be surgically excised and resected, or thermal cautery can be performed on the redundant tissue.

Pinguecula and Pingueculitis

A pinguecula is an extremely common benign, yellow/white elevated lesion found on the bulbar conjunctiva. It is often bilateral and asymptomatic. Pingueculae are caused by UV exposure and other elemental factors including wind and dust. This leads to elastic degeneration of collagen fibers in the conjunctival stroma. Similar to pterygia, they are more commonly found nasally.4 This is thought to be due to the internal reflection of temporal incident light across the cornea, resulting in 20-times the concentration of light focused at the nasal limbus.26,27

Mild symptoms of discomfort, itching and foreign body sensation can be treated with artificial tears. In cases of more significant inflammation, i.e., pingueculitis, a short course of soft topical steroids can be considered. UV protection is recommended to prevent progression. Surgical excision or removal with argon laser photocoagulation is rarely performed, except for cosmetic reasons.

Takeaways

The conjunctiva serves a critical role in ocular surface integrity. It does so by producing mucins and basal aqueous secretions to moisturize the ocular surface. It also serves as a physical barrier to foreign irritants and pathogens. As a highly vascularized tissue, it provides nutrients to its surrounding tissues and immunologic protection. Signs and symptoms of conjunctival inflammation can be nonspecific and have significant overlap between etiologies. It is critical to perform a thorough case history and careful ocular examination to tease out the nuances to make an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan.

Dr. Mannen practices at a private optometry and ophthalmology clinic in northern Utah. She completed her residency at the Walla Walla Veteran Affairs Medical Center and Pacific Cataract and Laser Institute. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. She has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Weisenthal RW, Afshari NA, Bouchard CS, et al. Chapter 1: Structure and Function of the External Eye and Cornea. In: External Disease and Cornea. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2013:3-4. 2. Hodges RR, Dartt DA. Tear film mucins: front line defenders of the ocular surface; comparison with airway and gastrointestinal tract mucins. Exp Eye Res. 2013;117:62-78. 3. Mantelli F, Argüeso P. Functions of ocular surface mucins in health and disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8(5):477-83. 4. Kanski JJ, Bowling B, Nischal KK, et al. Chapter 5: Conjunctiva. In: Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. 7th Edition. Elsevier/Saunders; 2011:132-66. 5. Conrady CD, Joos ZP, Patel BC. Review: the lacrimal gland and its role in dry eye. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:7542929. 6. Kirkwood BJ, Billing KJ. Membranous conjunctivitis from adverse drug reaction: Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Clin Exp Optom. 2011;94(2):236-9. 7. Sambursky R, Trattler W, Tauber S, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the AdenoPlus test for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:17-22. 8. Romanowski EG, Roba LA, Wiley L. et al. The effects of corticosteroids of adenoviral replication. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:581-5. 9. Romanowski EG, Yates KA, Gordon YJ. Topical corticosteroids of limited potency promote adenovirus replication in the Ad5/NZW rabbit ocular model. Cornea. 2002;21:289-91. 10. Shekhawat NS, Shtein RM, Blachley TS, et al. Antibiotic prescription fills for acute conjunctivitis among enrollees in a large United States managed care network. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(8):1099-107. 11. Melton R, Thomas R. Stop EKC with a ‘Silver Bullet.’ Rev Optom. 2008;145:11. 12. Weisenthal RW, Afshari NA, Bouchard CS, et al. Chapter 5: Infectious Diseases of the External Eye: Microbial and Parasitic Infections. In: External Disease and Cornea. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2013:135-45. 13. Karpecki P, Paterno MR, Comstock TL. Limitations of current antibiotic treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Optom Vis Sci. 2010;87(11):908-19. 14. Hutnik C, Mohammad-Shahi MH. Bacterial conjunctivitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:1451-7. 15. Seña A, Cohen HS. Treatment of uncomplicated Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. In: Marrazzo J and Bloom A, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, Massachusetts: UpToDate, 2021. 16. Tsubota K. Detection by brush cytology of mast cells and eosinophils in allergic and vernal conjunctivitis. Cornea. 1991;10(6):525. 17. Hamrah P, Dana R. Patient Education: Allergic Conjunctivitis (Beyond the Basics). In: Jacobs DS and Feldweg AM, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, Massachusetts: UpToDate, 2021. 18. McGill JI, Bacon A. Allergic eye disease mechanism. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1203-14. 19. Fujishima H, Saito I, Takeuchi T, et al. Immunological characteristics of patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002;46(3):244-8. 20. Allansmith MR. Treatment of giant papillary conjunctivitis. In: Flattau EP, ed. Considerations in Contact Lens Use Under Adverse Conditions: Proceedings of a Symposium. 1991. 21. Watanabe A, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S, et al. Clinicopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2004;23:294-8. 22. Francis IC, Chan DG, Kim P, et al. Case-controlled clinical and histopathological study of conjunctivochalasis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(3):302-5. 23. Liu D. Conjunctivochalasis: a cause of tearing and its management. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;2(1):25-8. 24. Erdogan-Poyraz C, Mocan MC, Irkec M, et al. Delayed tear clearance in patients with conjunctivochalasis is associated with punctal occlusion. Cornea. 2007;26(3):290-3. 25. Balci O. Clinical characteristics of patients with conjunctivochalasis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;28(8):1655-60. 26. Coroneo MT, Muller-Stolzenburg MW, Ho A. Peripheral light focusing by the anterior eye and the ophthalmohelioses. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991;22:705-11. 27. Coroneo MT. Pterygium as an early indicator of ultraviolet insolation: a hypothesis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77(11):734-9. 1. |