|

Q:

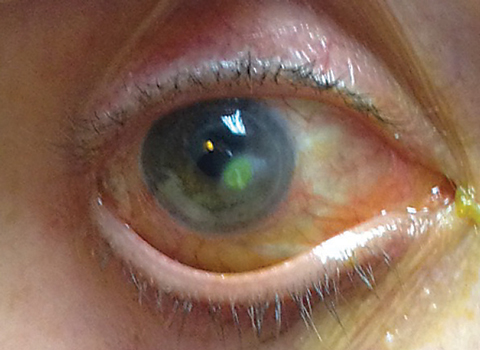

A middle-aged patient came to me with persistent central superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) in his left eye. After three doctors and weeks of artificial tears, steroids and antibiotics, he was still suffering. How do we solve this mystery?

A:

“With any patient who presents with keratitis or a red, irritated eye, always remember to evaluate the lids,” says Leslie Small, OD, of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. “Have them look up while pulling on the lower eyelids, and down while pulling up the upper eyelids,” she explains. This can help detect the less common condition of floppy eyelid syndrome.

Dr. Small follows a specific protocol to help guide her diagnosis. “I flip the eyelids, especially if it’s unilateral SPK. If you see that the eyelids evert easily, this will help guide you in your diagnosis,” she says, by indicating a problem with lid tonicity. In our patient, the left upper lid spontaneously everted just by pulling up on it. Dr. Small also suggests looking for sectoral injection by having the patient look in all fields of gaze.

|

| In cases of SPK that won’t go away, be sure to perform a thorough exam of the eyelids, as they may reveal the problem—and uncover a serious underlying non-ocular condition. |

Missed Connections

Why would doctors miss this condition? Dr. Small helps put the pieces together. Stated simply, “We tend to overlook the eyelids,” she says. “We tend to go straight to the slit lamp—it’s not super common for patients to have their eyelid elasticity checked by having them look up and down,” says Dr. Small.

When we see SPK, she says, “we automatically think dry eye disease (DED). Although floppy eyelid syndrome isn’t a rare disorder, DED is much more prevalent and carries greater incidence rates,” says Dr. Small. It may also be more symptomatic and bothersome for patients than floppy lid syndrome, although not necessarily.

Ask about history. Buddy Culbertson, MD, of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, first described the condition; in a study of men who suffered from obesity and tarsal papillary conjunctivitis, the affected side corresponded to the way the patients slept. Practitioners should take a thorough history, as this is crucial to nailing down this diagnosis, says Dr. Small. “Asking about sleeping habits can help solidify the diagnosis of floppy eyelid syndrome, as the SPK could certainly be from trauma-induced sleep habits as in this case,” Dr. Small says. Follow up questions on sleep apnea are important, such as a history of a sleep study or use of a continuous positive airway pressure machine. In this case, the patient admitted to snoring much of his life but had never been checked for sleep apnea. “When re-asked about how he sleeps, he later ‘remembered’ that he hugs his pillow with the left side of his face buried into it,” according

to Dr. Small.

A Solution to the Sag

If the patient is averse to surgical intervention in the form of lid tightening, for which Dr. Small is quick to refer—shielding the eye or eyes at night is the key to reducing the SPK and papillary conjunctivitis. “This involves keeping the eye protected from trauma so that the upper palpebral conjunctiva has time to heal,” says Dr. Small. These patients will always need a referral for a sleep study.

Finally, think carefully about this condition as it applies to your cataract patients, says Dr. Small. “If you’re going to be referring for cataract surgery, rule out floppy eyelid, as these patient are at increased risk for infection after surgery.”

Floppy eyelid syndrome is correlated with sleep apnea, which as we know is a potentially fatal condition, says Dr. Small. While we’re solving the sag, we’re also facilitating intervention on a related condition that has potentially deadly consequences if left untreated. So, before going to the lamp, check the lids. It could save the life of your patient.