One of the great challenges in any health care profession is differentiating between similarly appearing conditions. Based solely on clinical appearance, it can often be quite difficult to definitively diagnose a particular lesion, finding or presentation. However, visual cues are typically our first indication that something is out of the ordinary; we formulate a differential and bolster our presumptive diagnosis by gathering further clues from the history, patient demographics and associated findings. Ultimately, we may need to rely on ancillary medical testing, such as pathology reports or radiographic imaging, to ascertain the true etiology of a condition.

In this article, we present a series of contrasting cases with similar findings and attributes. We ask you, the reader, to test your clinical acumen by answering a series of questions following each scenario. These questions are intended to represent key issues that a clinician may need to consider when encountering a similar situation. Following each case, a discussion highlights the most crucial concepts to know when facing these challenges.

CASE #1

|

|

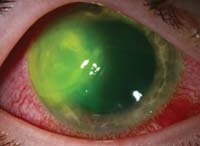

Above are two examples of patients who presented with acute red eyes. Both have a long history of contact lens use, and both were wearing their lenses when their eyes became red. Each patient reports pain, photophobia and excessive tearing in the involved eye.

Questions

1. Based upon the history and presentation, what can we assume about the etiology of these conditions?

a. The patient on the left has microbial keratitis; the one on the right does not.

b. The patient on the right has microbial keratitis; the one on the left does not.

c. Both have microbial keratitis, although the organism is likely different.

d. Neither has microbial keratitis.

2. The patient on the left is an otherwise healthy male in his mid-twenties. He was seen in your office Monday morning. He claims that he had no symptoms at all until late Friday evening, and that this all developed over the weekend. Given this information, what etiology must you suspect?

a. Bacterial infection, possibly Pseudomonas.

b. Corneal abrasion while sleeping.

c. Acanthamoeba.

d. Mooren’s ulcer.

3. The patient on the right is a 48-year-old female with controlled hypertension. She is an avid gardener and claims that her symptoms began after getting some debris in her eye about a week ago. She experienced initial scratchiness and discomfort, which improved slightly but then got progressively worse. Given this information, what etiology must you suspect?

a. Corneal foreign body.

b. Fungal infection.

c. Herpes zoster infection.

d. Disciform keratitis.

4. Which of the following therapies would potentially be of benefit in BOTH of these cases?

a. Oral acyclovir.

b. Topical besifloxacin.

c. Subconjunctival triamcinolone.

d. Amniotic membrane (e.g., ProKera).

Answers: 1) c; 2) b; 3) b; 4) d.

Discussion

Both patients have microbial keratitis. The patient on the left has a bacterial keratitis of pseudomonal origin; the patient on the right has fungal keratitis secondary to Fusarium. Both were definitively identified after corneal scraping and culture in the appropriate medium. While bacteria can be detected within a day or two, fungal cultures may take up to a week to demonstrate growth. Contact lens wear enhances the risk of microbial keratitis, and should be considered any time a patient presents with an acute red eye. Anecdotally, young males with poor contact lens care habits demonstrate more frequent bacterial ulcers. While fungal keratitis is far less common, a history of prior vegetative injury is a common element.

Acanthamoeba remains a potential etiology in virtually every early case of keratitis; however, it is still considered to be a rare occurrence by comparison. Also, the history of Acanthamoeba is typically slow and insidious, with persistence despite multiple therapies. Other cases of corneal trauma—such as foreign body, abrasion and recurrent erosion—usually are evident upon inspection; unlike microbial keratitis, these entities commonly present with a notable absence of corneal infiltrate.

Different microbial entities respond to different antimicrobial agents. Acyclovir is the prototypical antiviral agent used to manage herpetic infections, although there are several topical agents available (e.g., trifluridine, ganciclovir). A wide range of topical antibiotics are commercially available for the management of bacterial ocular infections, although only ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and ofloxacin are FDA approved for keratitis.

Corticosteroids remain a controversial management option in cases of microbial keratitis and should be used judiciously, even by those with great experience.

A relatively new therapeutic modality—a sutureless amniotic membrane suspended in a plastic ring—has been shown to provide antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic therapeutic elements that help to promote corneal healing. It is FDA approved for use in virtually all forms of microbial keratitis, and can be used in conjunction with topical and oral medications.

CASE #2

|

|

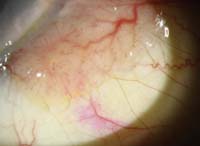

Above are two patients who presented with chronic unilateral redness for several months. Both are white males in their early 70s; neither patient reports significant discomfort or visual impairment. During examination, the patient on the right displayed staining of the circumscribed lesion with rose bengal while the patient on the left did not.

Questions

1. Based upon the history and presentation, what can we assume about the etiology of these conditions?

a. The patient on the left has a malignant lesion; the one on the right does not.

b. The patient on the right has a malignant lesion; the one on the left does not.

c. Both patients have malignant lesions, although likely of different cell origins.

d. It is impossible to definitively determine a lesion’s malignancy without biopsy.

2. Assuming the conjunctival lesions above are malignant, what diagnosis would be most plausible?

a. Squamous cell carcinoma.

b. Merkel cell carcinoma.

c. Amelanotic melanoma.

d. Kaposi’s sarcoma.

3. What common, benign lesion of the conjunctiva is often initially suspected of malignancy in elderly patients?

a. Squamous cell papilloma.

b. Phlyctenule.

c. Pinguecula.

d. Pterygium.

4. What course of action is most warranted for these individuals?

a. Photodocument and reassess in three months.

b. Initiate tobramycin/loteprednol QID and reassess in two weeks.

c. Refer promptly for excisional biopsy.

d. Refer for cryoablation at the patient’s convenience.

Answers: 1) d; 2) a; 3) a; 4) c.

Discussion

Newly identified lesions—or neoplasms—of the ocular surface must always warrant attention and consideration because of their potential for malignancy. This is especially true in patients over the age of 70. Unlike infectious or inflammatory disorders, ocular surface neoplasms often present insidiously and without significant discomfort or visual compromise. They may simply be noticed as an “unsightly bump” on the conjunctiva by the patient or another individual.

Many ocular surface neoplasms look similar, including those that are perfectly benign, such as papillomas, pingueculas and pterygia. Even malignancies exist as a continuum, from the borderline carcinoma-in-situ to the most severe invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Hence, there is no way to definitively identify a suspicious conjunctival lesion based on appearance or instinct. Definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy.

While both of the patients shown can be said to have neoplasms, only the patient on the right was diagnosed as having a malignant squamous cell carcinoma. The patient on the left was shown on biopsy to have a benign squamous cell papilloma—a common though often misdiagnosed conjunctival lesion of the elderly.

Key factors that should prompt greater urgency include two or more dilated conjunctival “feeder vessels,” leukoplakia (i.e., a patchy, whitish keratosis overlying the lesion which stains with rose bengal) and a history of rapid growth. All of these are considered red flags for squamous cell carcinoma, and all were noted in the patient on the right. Interestingly, a history of other forms of skin cancer does not necessarily dictate the disposition of an ocular lesion.

As mentioned, any suspicious lesion of the conjunctiva—especially in an elderly patient—should be referred promptly for excisional biopsy to confirm its etiology. Photodocumentation may be used to help initially differentiate the lesion or to monitor for changes in lesions known to be benign, but should not be considered a definitive form of management. Likewise, topical therapy with antibiotics and/or corticosteroids is often used initially when clinicians are unsure of the diagnosis, but this should be avoided as it can lead to patient complacency and non-compliance when the condition fails to resolve.

CASE #3

|

|

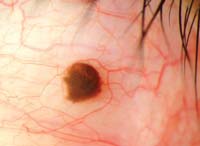

Both patients shown above presented with unilateral, pigmented lesions of the upper eyelid. The patient on the left noticed the lesion slowly progressing during the last four to five months; the patient on the right was referred by her primary care physician due to her “suspicious bruise.”

Questions

1. What common historical element might be anticipated in both patients?

a. Injections of onabotulinumtoxinA for cosmetic enhancement.

b. Atopic dermatitis with eczema.

c. Chronic or excessive exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

d. Elevated serum cholesterol and lipids.

2. The patient on the left is a 68-year-old female who vacations frequently in South Florida, where she is an avid golfer and boater. She has noticed the lesion on her left upper lid developing during the last year. Upon inspection, you find similar, smaller lesions on her hands, scalp and ears. What is the least likely presumptive diagnosis?

a. Actinic keratosis.

b. Basal cell carcinoma.

c. Sebaceous cell carcinoma.

d. Seborrheic keratosis.

3. The patient on the right is an 88-year-old white female who lives in the mid-western United States. She has advanced Alzheimer’s disease and cannot give an accurate history. A family member claims that the “bruise” on her upper lid was noticed about two weeks ago without any known trauma. Which of the following is not a red flag for potential malignancy?

a. Associated madarosis.

b. Non-uniform color and shape.

c. Location on the upper eyelid.

d. A satellite lesion at the outer canthus.

4. You determine that biopsy is necessary to definitively diagnose these lesions. To whom should this patient ideally be referred?

a. A board-certified oncologist.

b. A board-certified dermatologist.

c. A board-certified ophthalmologist.

d. A board-certified ocuoplastic surgeon.

Answers: 1) c; 2) c; 3) c; 4) d.

Discussion

Patients of advancing age are more prone to the development of both benign and malignant skin lesions. Papillomas, keratoses, keratoacanthomas, xanthelasma, carcinomas and melanomas are all seen in the elderly population with much greater frequency. Many of these conditions can trace their development to increased ultraviolet exposure, especially in fair-skinned patients. This includes a variety of malignancies (e.g., basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma), precancerous lesions (e.g., keratoacanthoma and actinic keratosis) and benign lesions (e.g., seborrheic keratosis). Interestingly, sebaceous cell carcinoma does not appear to be influenced by UV radiation or race.

The patient on the left has actinic keratosis, a precancerous lesion with a predilection for sun-exposed area of the face, scalp and hands. Typically, these lesions do not exist in isolation; inspection of other affected regions can help to narrow the diagnostic spectrum. They are relatively slow to arise, often developing over six to 12 months before they are detected or prompt patients to seek treatment.

Established red flags for cutaneous malignancy include such elements as abrupt changes in size, shape or elevation; irregular borders; predilection toward bleeding or scab formation; variability in coloration; and presentation at multiple locations (e.g., “satellite lesions”). When dealing with eyelid lesions, the localized or generalized loss of lashes—termed madarosis—is another important consideration that may portend malignancy.

As with conjunctival lesions, any suspicious lid lesion warrants biopsy evaluation, particularly when it is encountered in an at-risk patient. While many physicians may be able to perform a biopsy, eyelid lesions ideally require the technique be performed by a qualified and experienced oculoplastic specialist. This is because of their knowledge of the intricate and delicate elements of the eyelid itself, and the extremely important role the lid plays in protecting the ocular surface.

Further, in cases of confirmed malignancy, it is valuable to identify a surgeon who is proficient in performing Mohs micrographic surgery, which is the preferred technique for removing cutaneous malignancies and carries the best prognosis for complete eradication without recurrence.

CASE #4

|

|

Above are two examples of patients with pigmented conjunctival lesions. On the left is a 79-year-old white female with a history of cutaneous melanoma. On the right is a 34-year-old white male in otherwise good health. Both report mild foreign body sensation in the affected eye and stable vision.

Questions

1. Based upon the history and presentation, which patient warrants greater concern and urgency?

a. The 79-year-old woman on the left.

b. The 34-year-old man on the right.

c. Both require prompt intervention.

d. It is impossible to determine the level of urgency without biopsy.

2. What factors help to distinguish malignant conjunctival melanoma from benign conjunctival nevi?

a. Dilated conjunctival “feeder vessels.”

b. Multiple areas of involvement.

c. Variability of color within the lesion.

d. All of the above.

3. What factors help distinguish racial melanosis from benign conjunctival nevi?

a. Predilection for fair-skinned patients.

b. Unilateral involvement.

c. Tendency toward a circumlimbal presentation.

d. Notable at birth or early childhood.

4. Ultimately, what treatment is typically reserved for patients with invasive conjunctival melanoma?

a. Localized conjunctivectomy.

b. Enucleation or exenteration.

c. Focal irradiation.

d. Systemic chemotherapy.

Answers: 1) a; 2) d; 3) c; 4) b.

Discussion

Pigmented lesions, whether on the lid or conjunctiva, always warrant consideration and investigation. In general, round, regular, uniformly colored lesions of small size and long duration carry the lowest risk, while large, irregular, variably pigmented lesions of rapid progression are most suspicious.

The patient on the left was found to have conjunctival melanoma; in all, eight locations were biopsy-positive, including samples from her superior fornix and right lower lid. This underscores the importance of searching for “satellite lesions” when suspecting melanoma. This is an extremely aggressive form of cancer when it involves the eyelids or conjunctiva. Though therapies including local excision, radiation or chemotherapy may be employed, most cases ultimately involve enucleation or exenteration.

Conjunctival nevi are usually solitary lesions with distinct borders, as exhibited by our patient on the right. The color may range from pale yellow to dark brown, and can sometimes contain clear cystic lesions. Small, isolated nevi of long duration that have remained unchanged do not necessarily warrant aggressive action. Photodocumentation and periodic monitoring may be sufficient, but realize that in a very small percentage of patients, conjunctival nevi can undergo malignant transformation to become melanomas.

It is critical to differentiate nevi and melanomas from other forms of conjunctival pigmentation. Melanosis is a common finding in many practices. Dark-skinned individuals often display benign racial melanosis from an early age, which is generally bilateral and characterized by flat, even conjunctival pigmentation, often in a circumlimbal fashion. Acquired melanosis developing later in life can be more ominous.

Primary acquired melanosis (PAM) presents as flat, patchy conjunctival lesions, appearing unilaterally and typically occurring in fair-skinned patients. It has poorly defined margins and is usually located near the limbus. As many as 75% of conjunctival melanomas are believed to arise from PAM.

As with atypical lid lesions, should there be any doubt or concern regarding the disposition of a conjunctival lesion, excisional biopsy is warranted.

CASE #5

|

|

The two patients above presented for evaluation. The patient on the left has been having problems with her cornea “off and on” for several years, but recently relocated and cannot follow up with her regular doctor. She complains of reduced vision, mild discomfort and redness toward the end of the day. The patient on the right reports having steadily worsening redness, decreased vision and pain for the last month. She was treated with medication by another doctor but feels that there has not been any real progress. She wants a second opinion.

Questions

1. The patient on the left, a 35-year-old female, remembers that her previous doctor told her she had “herpes of the eye.” Her first episode was in 2003, and her most recent event was six months ago. She cannot recall the name of her medication, but claims that it was very expensive and the solution had to be used many times each day. Based upon this, what drug do you suppose might have been prescribed?

a. Moxifloxacin.

b. Acyclovir.

c. Trifluridine.

d. Loteprednol.

2. Upon examination, the patient on the left displays central corneal haziness at the level of the stroma, with a few keratic precipitates. Instillation of vital dyes reveals sporadic punctate staining with sodium fluorescein and none with rose bengal. What do you suspect is her diagnosis?

a. Herpes simplex epithelial keratitis.

b. Herpes simplex disciform keratitis.

c. Herpes zoster keratitis.

d. Acanthamoeba keratitis.

3. The patient on the right is a 48-year-old contact lens wearer. Coincidentally, she also indicates that she had been treated for a herpes eye infection by her prior doctor. She was prescribed Zirgan (ganciclovir ophthamic gel, Bausch + Lomb), which she used five times per day. However, since her condition did not improve, you suspect that:

a. She likely has some other type of microbial keratitis.

b. The medication she received was probably expired.

c. She has developed a resistant strain of the herpes virus.

d. She requires a corticosteroid in addition to the antiviral therapy.

4. Based upon your suspicions, what action would you take next?

a. Obtain scrapings and cultures and confocal microscopy of the lesion.

b. Start the patient on a new sample of Zirgan after checking the expiration date.

c. Start the patient on trifluridine 1% nine times daily and add acyclovir 400mg five times daily.

d. Start the patient on trifluridine 1% four times daily and add prednisolone acetate 1% eight times daily.

Answers

1) c; 2) b; 3) a; 4) a.

Discussion

The herpes virus can cause a wide range of ophthalmic presentations, and both herpes simplex and herpes zoster can be implicated. Classically, herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) presents as a dendritic epitheliopathy that stains centrally with fluorescein and peripherally with rose bengal. HSK may be painful initially, but with recurrent attacks, patients develop corneal hypoesthesia; although the eye may become red and inflamed, there is little subjective discomfort.

HSK responds very favorably to both topical and oral antiviral medications. Viroptic (trifluridine 1%, GlaxoSmithKline), Zirgan and

acyclovir are all extremely effective in arresting these infectious outbreaks. Topical acyclovir is only available outside the US, but the oral form can be used in lieu of topical medications at a dosage of 400mg five times daily for 10 to 14 days.

After the initial herpes simplex infection, it is possible to develop a noninfectious, cell-mediated immune reaction which stems from antibody/complement cascade against retained viral antigens in the cornea. Termed disciform keratitis, the condition presents with diffuse stromal edema that is almost invariably confined to the central cornea. Keratic precipitates and changes at the level of the endothelium may also be noted. This is the condition of our patient on the left. While disciform keratitis is often treated concurrently or prophylactically with antiviral medications (especially if the epithelium is compromised), the primary therapy required in this condition is a corticosteroid. Topical 1% prednisolone acetate (or equivalent) dosed every two to four hours is an excellent initial choice.

As mentioned, ocular herpes can take on a variety of presentations, many of which mimic other disorders. The patient on the right displays a large, ring-shaped infiltrate in her central cornea. But, according to her records, the earliest clinical findings included a dendritiform lesion––prompting her physician to initiate antiviral therapy. Further delving into the case revealed a history of contact lens wear and a corneal injury prompted by vegetative matter. These components, combined with the ring infiltrate and recalcitrant epithelial defect, must prompt the clinician to consider Acanthamoeba, a soil-borne pathogen that is often misdiagnosed upon initial presentation.

Acanthamoeba is a slowly progressing organism and will rarely present as a classic ring infiltrate. Therefore, it is not unusual for other, more common organisms to be suspected and treated first. A true classic finding of Acanthamoeba that may help in early suspicion of the organism is perineuritis, where the patient’s pain is disproportionate to the findings. Acanthamoeba can only be definitively identified with scrapings and cultures; however, confocal microscopy may yield the pathognomonic cysts when scrapings are negative. Most doctors now start therapy based on confocal findings.

Acanthamoeba is a very challenging organism to eradicate, typically requiring multiple drug therapy. While some antibiotics (e.g., polymyxin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) and antifungals (ketoconazole, miconazole) may be helpful, antiviral agents appear to have little impact on the course of this corneal infection. Unfortunately, unless suspected and treated early, many cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis ultimately necessitate penetrating keratoplasty.