|

In August, a 62-year-old black female was referred to our office for evaluation of her eyes, by a well-respected diabetes clinic that treats patients who cannot afford care and have no insurance or means to pay for services. It’s also known for encouraging timely eye care.

The patient reported that she had noticed difficulty with her distance and near vision since losing her glasses approximately six weeks earlier. She reported that her last visit to an eye care provider was four years earlier. Her medications included Januvia (sitagliptin), Tylenol as needed and a hypertensive medication that she takes once daily. She reported no allergies to medications.

The patient informed us that her primary care doctor was “not happy” with her A1c level obtained in June, but she did not know that value. She does not self-monitor with finger-stick glucose readings. She mentioned also that her doctor was considering starting her on insulin, which tells me that there was not consistent and adequate control of her glucose levels. She was not sure of exactly when she began diabetes medication, nor what her pretreatment glucose levels were, but she said that she thought she had been diagnosed about 10 years earlier.

|

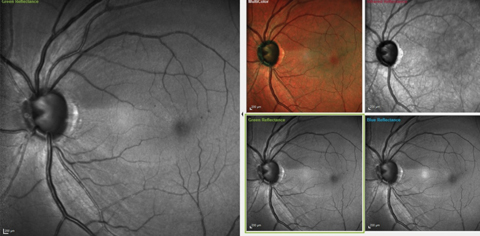

| Fig. 1. These images show the significant RNFL wedge defect located between the one and two o’clock positions, as well as a diffuse RNFL loss in the four to five o’clock positions. Microaneurysms are also visible perifoveally. Click image to enlarge. |

Examination

Uncorrected distance acuities were 20/60- OD and 20/50 OS, pinholing to 20/40 OD and OS. Best-corrected visual acuities through hyperopic astigmatic correction was 20/40 OD, OS, and 20/40+ OU. Pupils were equal, round and reactive to both light and accommodation, with no afferent pupillary defect noted.

A slit lamp exam of her anterior segments was unremarkable, with no evidence of iris neovascularization. Her anterior chamber angles were open. Applanation tensions were 20mm Hg OD and 23mm Hg OS at 2:30pm.

The patient was dilated with phenylephrine and tropicamide. Through dilated pupils, her crystalline lenses were characterized by mild cortical and nuclear cataracts, and there were bilateral early posterior subcapsular cataracts. I estimated that these lenticular changes accounted for a best-corrected visual acuity of about 20/30 OD and OS.

Our team noted bilateral posterior vitreous separations. Her cup-to-disc measurements were estimated at 0.7 x 0.7 OD and 0.75 x 0.85 OS. A retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) wedge defect was visible in her left eye consistent with glaucomatous damage. Her maculae were characterized by scattered microaneurysms, greater in the left eye than the right, with no discernible leak observed at the slit lamp, and the maculopathy did not meet ETDRS guidelines.

Retinal vasculature was characterized by mild arteriolar attenuation and mild crossing changes in both eyes. Her mid-peripheral retinal evaluation was characterized by scattered, and minimal, intraretinal hemorrhages consistent with mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Her peripheral retinal evaluations were unremarkable.

Since this was our first visit together, and diabetic maculopathy and uncontrolled glaucoma were noted, I chose to image her optic nerves and maculae with multicolor imaging as well as OCT that consists of: three diameter circle RNFL scans, Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) radial scans and macular scans with segmented retinal layers.

As she will need further evaluation, I scheduled a follow up visit in a couple of weeks, for threshold 24-2 visual fields, pachymetry, gonioscopy and Heidelberg Retina Tomograph (HRT 3) scanning of the optic nerves.

|

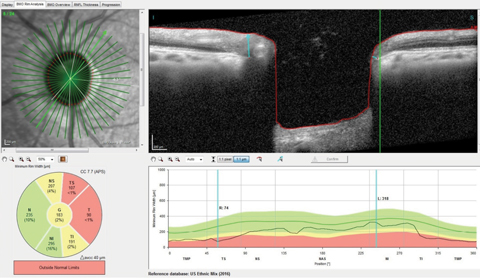

| Fig. 2. You can see the thinned superotemporal Bruch’s membrane opening radial scan with minimal rim tissue thickness in this scan at 74µm, well outside the reference database for normals. Click image to enlarge. |

Imaging Results

On multimodal laser imaging of the left posterior pole, not only was a rather large wedge defect seen in the superior portion of the papillomacular bundle and arcuate region, but diffuse retinal ganglion cell loss was also noted inferiorly in the left eye (Figure 1). Superior temporal BMO in the left eye demonstrated a minimum rim width (MRW) of only 74µm in the area of the wedge defect (Figure 2).

The RNFL circle scans of that eye demonstrated a statistically significant aberration in the temporal and inferotemporal Garway-Heath sectors in the 3.5mm and 4.1mm RNFL circle scans.

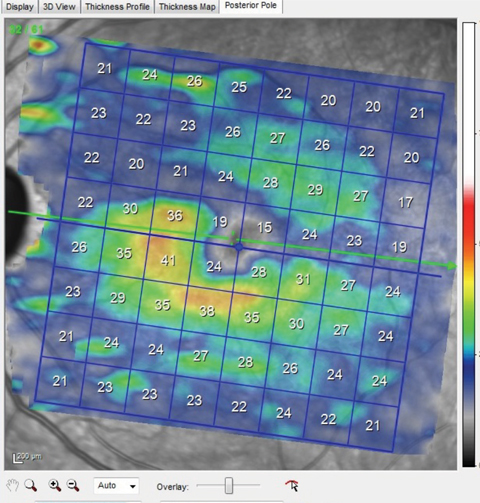

Macular OCT scans of both eyes demonstrated ganglion cell layer defects in the areas consistent with the multicolor images and the wedge defect and RNFL diffuse defects seen clinically (Figure 3). In essence, all the pieces of the puzzle fit together perfectly.

Diagnosis

At the completion of this first visit, I determined that the patient had mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, no clinically significant diabetic macular edema and uncontrolled glaucoma in both eyes, but more so in the left than the right.

She presented for follow up as scheduled. At that visit, visual field studies demonstrated field defects consistent with the clinical picture seen at the previous visit, with above and below arcuate defects in her left eye encroaching upon fixation.

Her pachymetry readings were 530µm in the right eye and 535µm in the left. Applanation tensions at this follow up visit were 21mm Hg OD and 22mm Hg OS at 2:45pm. HRT 3 studies confirmed the clinically estimated cup-to-disc ratios and correlated well with the OCT BMO profiles obtained earlier in both eyes. A gonioscopic exam demonstrated open angles, with a flat iris approach and moderate trabecular pigmentation in both eyes.

After the visit, the patient was educated about a firm diagnosis of open-angle glaucoma, and a sample of Travatan Z was given to her with instructions on drop instillation and directions to use one drop in both eyes at bedtime. As of this writing, she is scheduled for follow up in two weeks to assess the efficacy of this medication as well as tolerability.

|

| Fig. 3. Note the thinned ganglion cell layer above the horizontal meridian that matches perfectly with the wedge defect seen in the multicolor image shown earlier. This macular ganglion cell layer thinning also matches up to the thinned superotemporal BMO scan also shown earlier. Click image to enlarge. |

First, Do No Harm

So, what’s the catch here? This seems like a straightforward case of a new patient presenting with undiagnosed glaucoma, who also happens to have diabetes with mild retinopathic findings. The patient was imaged using the latest technology and software, underwent threshold visual fields, and findings from the structure, function and clinical exams all added up and made sense. She was exhaustively tested to confirm what I suspected from the first visit: this patient has glaucoma that needs to be treated. Both visits demonstrate straightforward, textbook findings, imaging and management.

But this case contained one key difference.

The patient was referred from a clinic in town that sees patients who fall through the cracks. We’ve all seen patients like these where we comp our services, in the interest of providing good care to all people, independent of whether or not we get paid. I’m no hero for seeing this patient; every doctor does some measure of this as circumstances allow. Sometimes doctors offer patients in these situations services, to be sure—but with a reduced level of care. With all the technology available to us, we could have skipped many of the studies that we typically run our glaucoma patients through. We certainly have tests that could have been eliminated in this case that would not have affected her ultimate diagnosis. But to what end? To save a few bucks? To save some time? Although the patient could not pay for her services, she still deserves the best care I can provide. No need to shortchange her.

Do what is right. We did it all, we got paid nothing, but, by going all-out, we both have everything to gain.