|

We consider the challenge of providing excellent vision care to be vital for all of our patients. But in athletes, the stakes are especially high: their performance in the chair often correlates directly with their performance on the field. And in dangerous contact sports, sharp vision can keep them free of injury or incident. Sports vision cases are illuminating in helping us understand the unique challenges athletes face and teach us valuable lessons applicable to everyone.

This installment of Focus on Refraction draws from our recent experiences in sports vision at Southern College of Optometry (SCO), which now provides comprehensive sports vision care for athletes attending the University of Memphis (UM).

|

| Defensive and offensive linemen in battle. |

We recently screened the first one-third of the student athletes—147 athletes—and identified roughly one-third of these 147 to be in need of comprehensive sports vision evaluations. Vision correction and vision therapy was then provided, if determined necessary.

One athlete, J.D., noted on the screening questionnaire that he has a refractive prescription but hasn’t worn glasses or contacts for more than one year. In response to the question, “Do you ever feel yourself making visual errors?” he responded, “Yes, when finding the football.” J.D. plays an inside position on the football team’s defensive line and has two more years of time left in his college career.

J.D.’s unaided visual acuities were 20/22 OD and 20/40 OS. He saw nothing on the Random Dot 3 stereo test and had some intermittent suppression Brock String. When he did see the two strings, they met closer to him when he looked at the bead furthest away from him, but they met further away from him on the near and intermediate beads. Based on the results of this screening, J.D. was brought into SCO’s University Eye Care center where the UM athletic vision program (AVP) is being conducted.

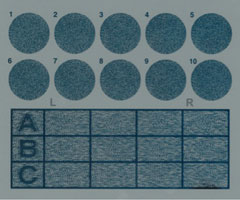

Table 1. Refractive WorkupDistance retinoscopy: Binocular balance (most plus to the first good 20/20 done binocularly): Second refractive endpoint**—i.e., the lens through which he saw the 20/20 letters to be perceptually the largest: Following this, we did the rest of our binocular testing. The key findings included: |

Player’s Stats

During our 90-minute AVP evaluation, we took a thorough history. We found that J.D., an interdisciplinary studies major with an emphasis in health, holds a GPA in the high twos. During the evaluation, he noted that he reads slowly and he has to reread many things to come away with full comprehension. When asked about the strongest aspect of his play on the field, he said it was getting to the quarterback. He denied having suffered from TBI but stated that, on at least four separate occasions, he wondered if he had sustained injury following hard hits on the field.

|

| Large shapes are graded from 600 to 400 seconds of arc. These 10 circles on the top grade down to 12.5 seconds of arc. The three lower rows have Lea symbols with intermediate stereo values. |

He denied seeing double. He did not have his glasses with him; he hadn’t worn them for more than a year. He never wore contact lenses. His last comprehensive visual evaluation occurred in 2013 in his home state, prior to college.

We performed our refractive workup on J.D. (Table 1). His visual acuities were found to be nearly identical to what was found at the visual screening: 20/21 OD and 20/39 OS. At near, he showed 20/20 in all conditions, but he held the target much closer than normal working distance—nine inches. His cover test varied at times, which showed near-ortho and moderate to high exophoria. His near point of convergence showed an eight-inch break and a 14-inch recover; his left eye went out objectively, though he never reported seeing double.

After a battery of tests, the most significant finding was this patient’s performance with the ReadAlyzer (Compevo), an infrared eye movement recording device. We had to drop to an eighth grade level reading card in order for J.D. to score the minimum 70% on the comprehension test. In fact, he performed much higher—90%—on the eighth grade scorecard.

His reading speed was 140 words per minute—one-half the speed expected for an adult-level reader. He stopped 123 times to read 100 words, 37% more than expected—a fifth grade level. He showed only six regressions (going backward within a line of text to reread it), which is actually better than what we expect for an adult-level reader. His average duration of fixation was 0.34 seconds, the expected value for a first grader. This usually signals that the person discusses the story and data (to themselves) during the reading to help them remember.

|

| Performing the Random Dot 3 (left) and Brock string tests (right). |

|

| The ReadAlyzer saccadic test being used on a student athlete. |

|

| SCO students screening athletes from a local college. |

The Game Plan

Herein lies the primary dilemma: What do we prescribe? We had a conundrum, and a thorny one at that. The patient shows very poor binocularity. We cannot correlate the cause and effect because this patient was new and we did not have access to his previous exam data. Thus, whether or not the poor binocularity led to his suppression and blurring of the left eye’s input or vice versa did not weigh into what was prescribed.

We do know from experience, however, that if all of a sudden he gets two clean streams of data, he doesn’t have the software to use them seamlessly. And that’s not taking into account the spatial changes one gets with cylinders like that.

Fortunately, we were at least three months from the football season, and the patient is in his junior year. A third member of our sports vision team, Christina Newman, OD, will fit him with contact lenses for maximum visual acuity as we simultaneously commence a vision therapy program.

The contact lenses alone will not address J.D.’s severe binocular dysfunction, which manifests as dual convergence and accommodative insufficiencies. We initiated an intensive vision therapy program, to help J.D. learn to balance use of his two eyes together and to make quick spatial adjustments on the field and in the classroom.

We considered whether or not it would suffice to prescribe one contact lens on his left eye. However, we felt the jump from 20/21 unaided to 20/14 with the cylinder in place would be quite significant in high-level, division I NCAA sports, so we elected to fit contacts for both eyes.

Lastly, we considered whether to prescribe glasses at all or opt only for contact lenses. Of course, we recognize that all patients who wear contact lenses will face circumstances when they should not wear their contacts, in which case their glasses become an emergency backup. At this point in his care, the spatial distortions caused by glasses could amplify the binocular issues too much to be practical for J.D.

4th and Goal

This clinical experience tells us two important things. First, when working with athletes it is important to instill confidence that we can and will help them from the get-go. In this light, prescribing glasses that would amplify J.D.’s problems was not conducive to a good working relationship. Second, this case tells us that once the binocular problems have been addressed sufficiently, glasses can be prescribed, which will be adapted to rather easily.

Note: The visual acuities reported here have finer gradations than are part of normal charts. We use the M&S Technologies Smart System with a program that allows for continuously variable-sized Sloan letters; the user employs a step program to find thresholds which are quite accurate and repeatable.

For more on refractive targets, see our prior column “The Endpoint Endgame,” December 2015, p. 28.