|

Q:

I have a patient who presented to his family doctor with complete right upper lid ptosis. The doctor diagnosed the patient with conjunctivitis and gave him a topical antibiotic for “stuck shut lid.” Beyond a quick look, the eye was never examined. How do I work up this case, and what are some lessons learned for those of us not comfortable with neuro conditions?A:

“First, perform an external exam on the patient, which includes watching the patient walk to the exam room,” says Trennda L. Rittenbach, OD, of the Palo Alto Medical Foundation in Sunnyvale, Calif. For instance, “if the patient has an unsteady gait, is tilting to one side, is unable to walk unassisted and has never had these issues before, you may be dealing with underlying neurological disease,” Dr. Rittenbach advises.Case history, pupils, EOMs and confrontation fields are the critical exam aspects in cases where there is a suspected neurological etiology, says Dr. Rittenbach. Here, she gets us up to speed on the details of each:

|

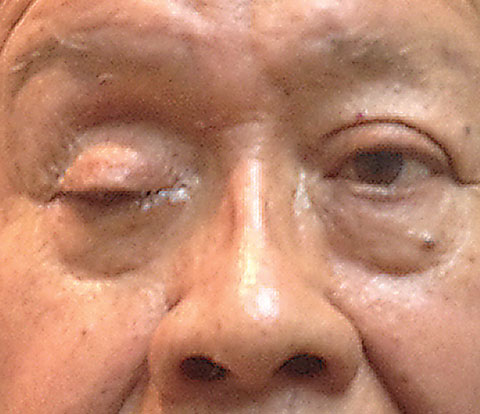

| Complete ptosis could indicate the presence of an emergent neurological condition. Photo: Michael Trottini, OD |

Pupils. It’s imperative to rule out pupil involvement. A blown pupil is an emergency, without question.

Motilities. These findings are critical to identifying the problematic nerve. Since there is no way you can evaluate motilities with an eye closed, lift the eyelid, instructs Dr. Rittenbach. “In this particular case, the patient had a complete ptosis of the right eyelid. When I lifted up the ‘stuck shut lid,’ the patient saw two of me and his eye was down and out.” Dr. Rittenbach says the patient was unable to adduct the right eye, unable to look up and had limited ability to look down, but abduction was intact and preserved.

Confrontation fields. These were full OD and OS, which helps rule out a stroke or compressive lesion.

Dr. Rittenbach made the diagnosis of a pupil-sparing, complete right third nerve palsy. But, the question still remained: ‘What is the cause?’ The answer could mean the difference between a trip to the emergency room, a trip to the pharmacy or simply a trip home.

What’s Causing the Palsy?

Dr. Rittenbach says it’s imperative to order blood work to rule out giant cell arteritis. “A complete blood count with differentials, sedimentation rate and a c-reactive protein are crucial to rule out giant cell arteritis in all third nerve palsy cases in patients older than 50 years,” Dr. Rittenbach says.1Taking blood pressure and knowing a diabetes patient’s last HbA1c is helpful to determine if the underlying cause is ischemic, says Dr. Rittenbach. If you have evidence that the diabetes is out of control, a referral to the patient’s primary care provider or endocrinologist is appropriate. “In addition, I arranged a STAT neuro consult, which isn’t always easy, depending on where you practice. The neurologist will most likely order imaging, including a computed tomography angiography test.2 Most ODs don’t work in a hospital setting, so establishing a good working relationship with neurology is critical for when you encounter emergent cases,” she says.

Fortunately, in this case, the etiology was ischemic due to elevated blood sugar rather than an intracranial mass or aneurysm. The problem resolved with aggressive blood sugar control after about 12 weeks.

| 1. Thurtell MJ, Longmuir RA. Third nerve palsy as the initial manifestation of giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014 Sep;34(3):243-5. 2. Mathew MR, Teasdale E, McFadzean RM. Multidetector computed tomographic angiography in isolated third nerve palsy. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1411-15. |