Each day, health care professionals evaluate, diagnose and manage medical conditions knowing there is the possibility for malpractice litigation. In eye care, optometrists encounter many ocular conditions with systemic etiologies and many systemic pathologies that have ocular signs and symptoms, which when missed can have devastating consequences.

The provider’s ability to properly connect the dots of a patient’s complaints starts with careful observation of each part of the eye and thorough documentation. The greater the volume, the more tempted a provider may be to cut corners, skip tests and document incompletely. This opens the door to missed or erroneous diagnoses and, in some cases, improper treatment and failure to refer in a timely manner.

Developing a “legal protections” protocol for the office can significantly reduce your risk of being sued. To achieve that, you’ll need to: (1) effectively recognize the areas of eye care most susceptible to legal peril (2) thoroughly understand how to navigate the contractual doctor/patient relationship; (3) know communication dos and don’ts to abide by with any patient who may have been potentially harmed and (4) promptly and properly respond to a formal legal summons.

Why ODs Get Sued

What legal issues should be most concerning to optometrists practicing in the 21st century healthcare setting? Optometric malpractice in years past was significantly different than our current day concerns.

Consider a 1941 case from an appellate court in Georgia, where “the Optometrist had not exercised reasonable care and skill in his examination of the eyes of his patient, a schoolboy, and in the fitting of glasses on the eyes.”1 The court’s ruling described the injury, or tort, of the plaintiff “[as] suffer[ing] headaches and nausea and [being] ‘backward’ in his school work.” The court ultimately awarded $75.00 to the plaintiff.1

Compare that relatively benign injury and nominal award with a more recent ruling for “failure to refer,” whereby a plaintiff suffering from significant nearsightedness was not evaluated until the Monday after suffering from and reporting symptoms of floaters and flashes of light on the previous day. What did it cost the provider for that mistake? The macula-off retinal detachment with severe and permanent visual impairment in one eye resulted in a jury award of $2.5 million to the plaintiff.

These types of judgments rendered against providers, or more often settled out of court by professional liability insurance companies on behalf of providers, are extremely stressful and demoralizing. And, each settlement or judgment, even when paid by insurance companies, eventually exerts costs to providers in the way of increasing malpractice premiums. Having a triage system and “after-hours” plan before incidents occur is just one of the many procedural changes optometrists should establish in clinical practice to avoid medical harm and lawsuits.

First, know which local hospitals have surgical retina providers on duty 24 hours per day, seven days per week (typically teaching hospitals) or establish a direct connection with your preferred retina practice whereby patients can be triaged directly by the specialist. Additionally, institute a triage phone questionnaire to remove “judgment calls” by staff when fielding calls. As a result, instructions are explicit based on the intake answers provided by the patient and delayed evaluations are eliminated.

|

|

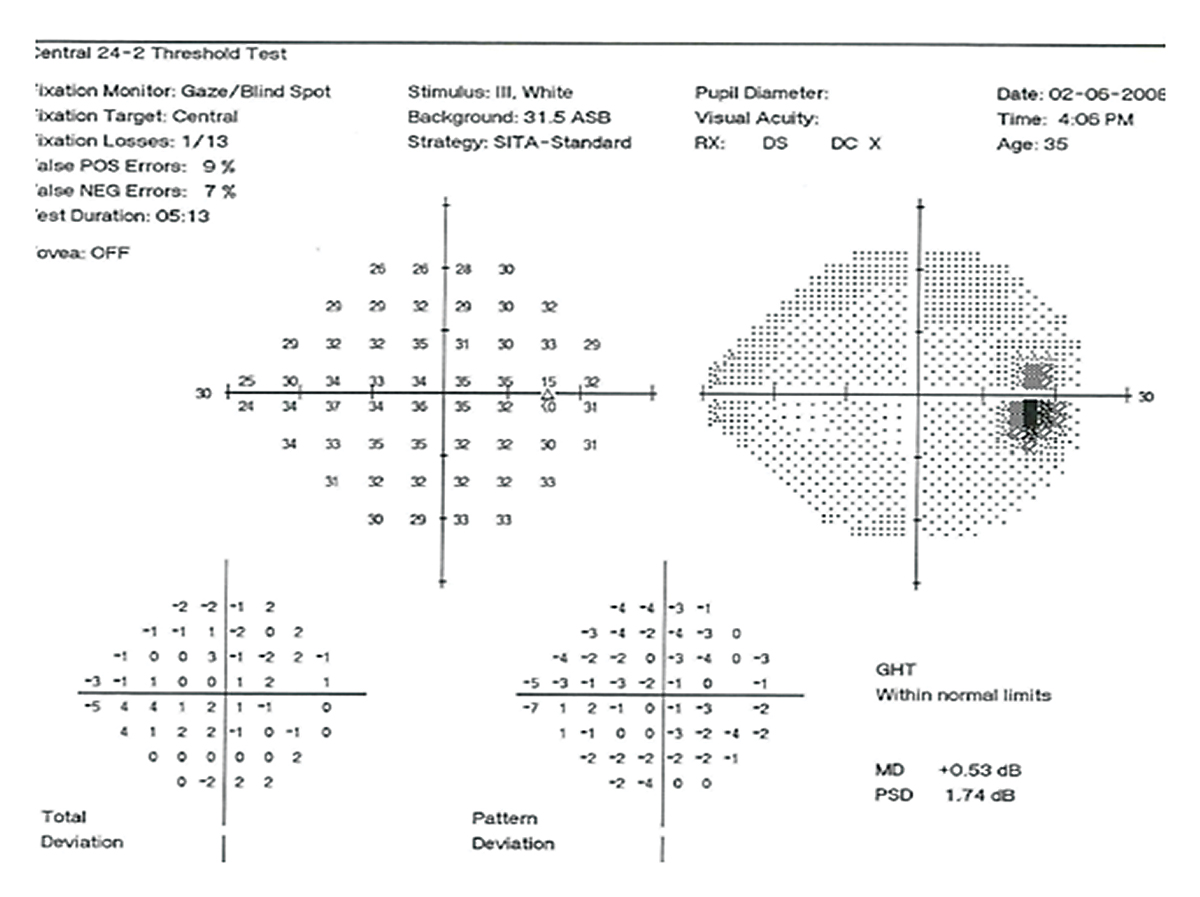

Fig. 1. Patient’s results on 24-2 SAP VF appears “normal” however there is masking of an actual early glaucomatous defect due to the patient’s high “false positive” responses (9%). Click image to enlarge. |

Failure to Diagnose

In eye care, most negligence cases arise from a “failure to diagnose,” particularly around patients with glaucoma. Why? Because glaucoma typically presents without symptoms and the clinical signs can be missed if the patient’s optic nerve, neuroretinal rim and retinal nerve fiber layer analysis are performed improperly, particularly without pupil mydriasis.

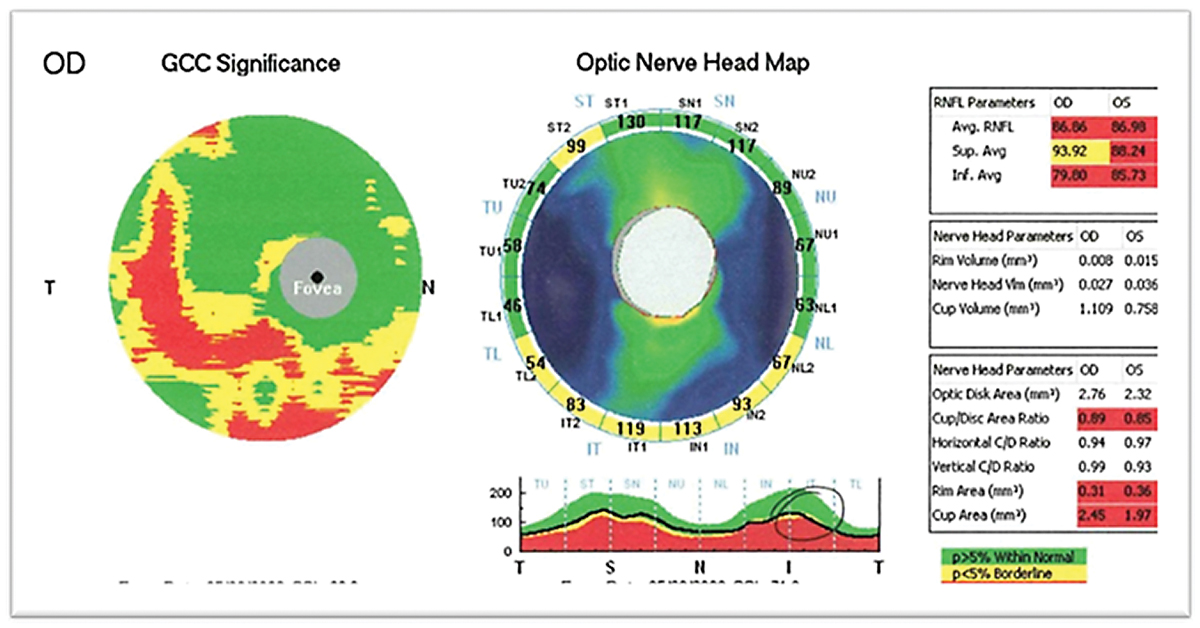

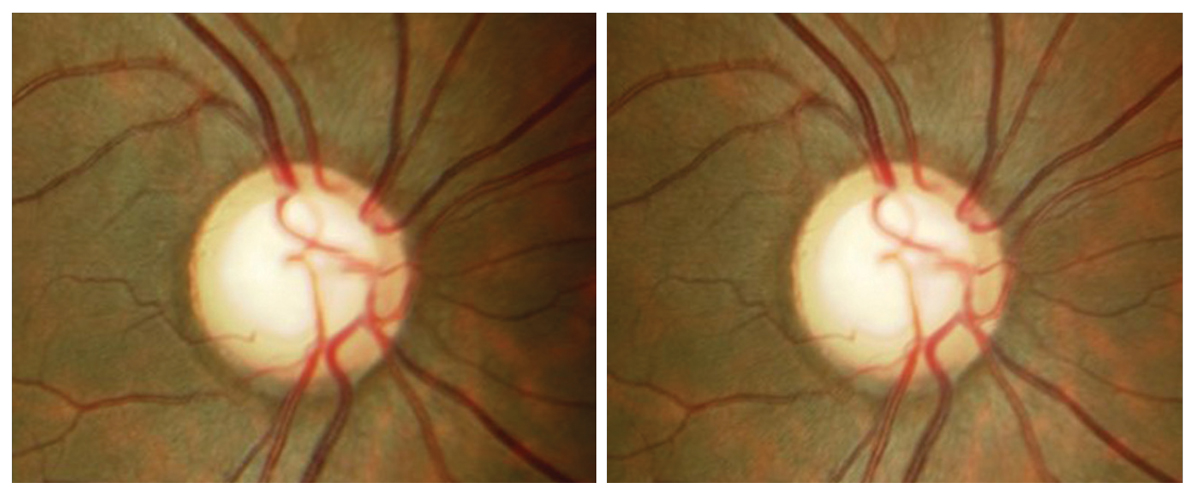

Consider the risk of a non-mydriatic evaluation in the following case (Figures 1-3). A non-stereoscopic optic nerve evaluation and the patient’s initial visual field does not indicate any glaucoma or significant loss of vision. However, careful stereoscopic examination of the optic nerve and optical coherence tomography (OCT) highlight early inferior optic nerve damage, ganglion cell loss and reduced retinal nerve fiber layer thickness consistent with the inferior-temporal thinning/sloping of the neuroretinal rim tissue.

Undilated viewing and reliance on subjective visual field data, or worse yet, “normal-range” intraocular pressure readings, might cause a provider to fail to diagnose the glaucomatous optic neuropathy present in this case.

In eye care, nearly all serious incidences of “missed” diagnoses are tied to examining patients without dilated fundus examinations using slit lamp and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy techniques. In glaucoma care, significantly greater congruency of the “actual” cup-to-disc ratio with interpreted ratios is found in dilated evaluations versus undilated examinations.2

One of the easiest ways to avoid claims of misdiagnosis of intraocular disease, including retinal breaks, tears and detachments, open-angle glaucoma and malignancies (ocular and brain tumors) is to routinely use diagnostic agents for dilation of the pupil during ocular examinations.

Unfortunately, providers occasionally fail to dilate patients due to patient complaints about post-dilation blur and photosensitivity as well as the increased examination time added to the visits. Designing practice protocols and procedures around actively dilating patients annually allows for the most effective ocular examinations and reduces malpractice risk significantly.

Keeping current on the latest technologies and treatment options through continuing education courses and colleague collaborations will, undoubtedly, prevent application of outmoded standards as new and improved options are introduced and adopted by the profession.

An audit of patient records and state board complaints initiated by patients against providers highlights both documentation errors as well as clinical decision making shortcomings that lead to litigation.

The areas of greatest concern that repeatedly arise include: (1) providers recognizing and documenting a clinical finding as “different” or concerning (e.g., “possible optic nerve pallor”) but not initiating steps to investigate further (i.e., imaging, blood work, referral, etc.), (2) documenting a finding that is significant (e.g., “new-onset floaters”) but not initiating the proper expanded documentation or testing (i.e., questioning for associated findings such as flashes or veil/curtain effect and performing dilated fundus evaluations or referral) and (3) performing a complete and thorough evaluation with proper assessment and plan but failing to fully document information collected during the course of the examination.

|

|

Fig. 2. Patient’s OCT OD demonstrates large ratio cupping with inferior thinning of the RNFL and corresponding GCC consistent with glaucomatous optic nerve atrophy. Click image to enlarge. |

Defining Negligence

Now before you panic and double-up all your malpractice coverages, understand that the legal standard for negligence requires four main elements that all must be satisfied before a judgment can be rendered: (1) Duty of Care, (2) Breach of Duty, (3) Injury and (4) Causation.

In legal proceedings, this is often a very difficult threshold to meet, and many lawsuits fail on inconclusive causation findings or disputes on standards.

In fact, there has rarely, if ever, been more than 50 total optometric malpractice judgments in any given year across the entire United States—an amazing statistic considering ODs are the leading providers of primary eye care services. With more than 35,000 full-time employed ODs practicing in 7,000+ communities and 4,300+ towns having ODs serve as the only source of primary eye care, such a minimal number of lawsuits is all the more impressive.3 Contributing to the exceptionally low incidences of malpractice is the fact that optometrists: (1) do not perform intraocular surgery, (2) endure a rigorous optometric doctoral program for entry to practice and (3) benefit from the “all or none” requirements of negligence in legal proceedings.

Typically, the elements in cases determining legal outcomes mainly revolve around Breach of Duty and Causation findings since the “standards” of eye care are generally well-established. As the injury is typically evident (loss of visual acuity, visual field or both), plaintiffs will be claiming some level of loss of function/ability to bring suit.

If our lack of action, delayed action(s) or improper action(s), as their provider, was directly responsible for the injuries that followed, then the only remaining “lifeline” in obtaining a “not guilty” verdict is whether or not we were following the “standard of care” throughout the doctor/patient exchange without breaching that duty.

In the event the injury suffered by the patient was inevitable regardless of the care that was applied at the time of presentation to the doctor’s care, there will not be an enforceable negligence ruling and the plaintiff’s case will be unsuccessful.

In current case law, the standard of care is established as the care that would typically be rendered by those who provide “reasonable and ordinary care,” skill and diligence as physicians and surgeons in good standing practicing “in the same neighborhood,” in the same general line of practice, [who] ordinarily have and exercise in like cases. It is not measured against the most knowledgeable [expert] of peers/colleagues in the profession but it has and continues to evolve as technology and treatment protocols evolve.4

Consider that before collagen crosslinking (CXL) become FDA approved, our standard of care in corneal ectasia cases (keratoconus/pellucid marginal degeneration/post-refractive surgery) was to manage “vision” with contact lenses until apical corneal scarring necessitated corneal transplant surgery. That protocol is no longer acceptable since CXL can arrest ectatic advancement and prevent loss of vision normally associated with scar development.

A provider who would fail to refer for CXL would be negligent and open to malpractice litigation. In the end, our practice decisions are compared with the average physician in the same line of practice and alternative treatments or experimental techniques are acceptable only if a respectable minority recognizes it as “reasonable medicine” or if all other standard treatments have failed and serious consequences are imminent.

In the world of eye care, the Injury component of negligence can be as minimal as asthenopia-related symptoms, as demonstrated previously, to severe visual impairment or even resultant death (failure to diagnose malignancies/tumors).

|

|

Fig. 3. Patient’s right eye stereoscopic optic nerve images. Notable is the inferior temporal sloping and thinning of the neuroretinal rim tissue that would be difficult to detect without stereoscopic viewing. Click image to enlarge. |

Put into Practice

So, having established a macro view of the malpractice minefield, it’s probably prudent to reflect on how we most often become entangled in legal jeopardy in our practices day-to-day along with the mechanisms to mitigate that risk:

Contractual Relationships

The doctor/patient relationship is a consensual one wherein the patient knowingly seeks the assistance of a physician and the physician knowingly accepts them as a patient. However, once we have established that relationship, we are responsible for providing healthcare in a manner consistent within the “standard of care” of the eye care community.

We can only “disengage” from the established doctor/patient relationship when: (1) the patient is cured or dies, (2) when the physician and patient mutually consent to termination, (3) when the patient dismisses the physician or (4) when the physician withdraws from the doctor/patient contract.5

Now, of course, for a number of reasons, a relationship between the doctor (or the doctor’s staff) and a patient may no longer be suitable (e.g., behavioral issues, treatment non-compliance), and it is best if the parties go their separate ways. It will be necessary for the clinician to initiate a rational discussion expressing how issues in the relationship are making care counterproductive and that a referral to another provider is necessary where the patient might have better success and outcomes.

This referral ultimately needs to be confirmed, in written form, that your colleague has assumed the care of the patient to avoid abandonment and breach of contract charges. As a rule, have your office manager/front desk staff make the appointment for the outgoing patient while they are still at your office to be sure you have provided sufficient time and access for the patient to find a replacement provider. Lastly, obtain documentation that another physician is now actively managing the patient and you’ll satisfy your legal obligations under the law.

How to Respond to a Summons

Formal legal summons, records requests by attorneys and/or patients or informal complaint letters regarding one of your patients requires the following actions: (1) immediately contact with your malpractice carrier (legal summons require responses of guilty/not guilty typically within 30 days or risk of a default judgment against you) and a personal malpractice attorney, (2) take a deep breath—this is why you have malpractice insurance and (3) realize that while this will be a source of stress and frustration, you will continue to care for patients and protect your livelihood.

In the event that an amicable solution cannot be arrived at, your insurance provider will also be assigning its in-house counsel to manage your case, but having your own personal representation is always sound advice.

Finally, a system to prevent medical chart records and billing information from ever leaving your office without your review (see below) is important every day but even more critical during these potential legal proceedings.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) legislates that our patients have a right to a copy of their medical record; however, no statute dictates that the review or release needs to be immediate, and usually up to 30 days is allowable before running afoul of the law.4 Providers can and should provide records to comanaging physicians in a timely or expedient fashion especially if the patient is in an emergent or urgent health crisis, but beyond that, a process for review and then release is critical.

Completing records accurately and completely at the time of service can avoid omissions and/or mistakes that occur when backfilled long after the visit has occurred and memories are blurred.

Documentation and Preparation

Incomplete or inaccurate charts (paper or electronic) are the low-hanging fruit for malpractice litigators. If it’s not written, it didn’t happen.

Did you have a discussion about potential visual loss in the event the patient is noncompliant with medication usage but didn’t document the discussion? Well, it didn’t happen in the eyes of the court. Did you modify or “clean up” a medical record (paper or electronic) after receiving a “discovery” patient record request from the plaintiff’s attorney (they likely already attempted to obtain a copy of the chart from your front desk staff on an earlier benign request)? If so, you’ve just handed the suing party an automatic victory even if the changes were an accurate representation of those visit(s).

Enforce an office-wide, written, firm chart and form policy (punishable by immediate termination) that no copy of any patient record requested by anyone (e.g., patients, proxies, colleague providers, government entities, plaintiff’s attorneys) is ever released without prior review and authorization from each and every doctor within the practice that has contributed to the medical record and an in-house document placed at the fore of the chart (paper or EMR) describing the request type (e.g., notes, images, billing), requestor(s) and the authorized release date.

It’s always best to make a habit of completing patient visit medical records by the end of the business day, if not by the end of the actual encounter for the greatest accuracy and precision. The end result is confidence knowing that the records and materials are accurate and represent the full and complete story of the patient’s rendered care. For most optometrists providing excellent care to their patients, there is nothing more important in those legal proceedings.

|

|

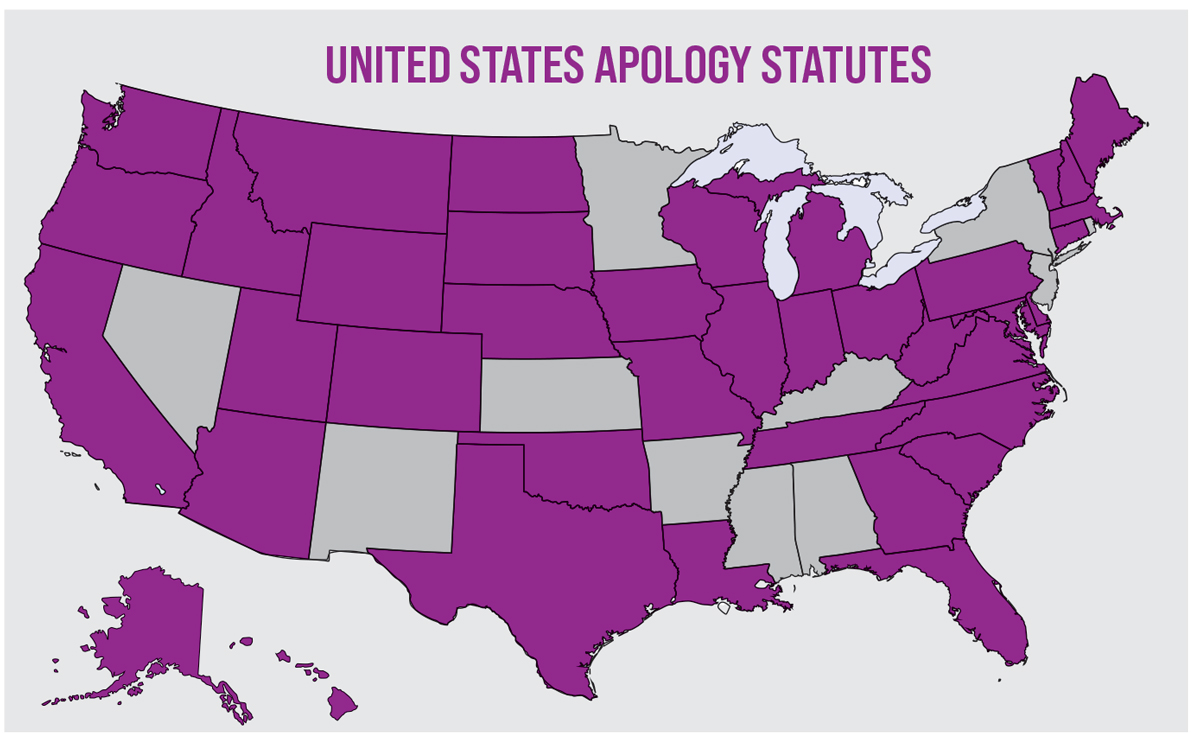

Fig. 4. US map highlighting the 39 states currently with legislation enacting “I’m Sorry” statutes and or provisions. Click image to enlarge. |

After-incident Communication

A poor patient outcome resulting in visual loss or reduction is not necessarily medical malpractice. In fact, many poor outcomes occur while under the care of expert clinicians managing cases meeting or exceeding every standard of care. In other words, some poor outcomes are not preventable despite the best treatments and care.

What is preventable is poor communication between providers and patients. And, while patients ultimately know that doctors are human and capable of errors, it is not perfection they are seeking.

A significant contributing factor that induces a patient towards medical malpractice proceedings is the unsatisfactory communication before, during and after a perceived or actual patient injury. Patient polling, depositions, interrogatories and casual conversations all point to patient frustrations and, more importantly, anger originating from a provider’s minimization, trivialization, dismissal or outright avoidance of patient complaints after an outcome or incident has resulted in a poor outcome.

The adverse event, unfortunate and sometimes vision impairing, is not the impetus for initiating most lawsuits but rather the feeling that the doctor does not care, particularly when the silence afterwards is deafening to them. The doctor/patient relationship is ultimately based on trust and communication and once that foundation has been eroded, the patient may look to force that communication and “get answers” for their concerns in any manner possible—only at this juncture will they use the courts and attorneys as their conduit rather than a phone call to the office.

To get ahead of this potential litigation, enact an “office grievance communication policy.” Define a written policy playbook instructing all members of the office team how to properly respond (or not respond) to patient complaints (minor and major) based on the following principles and research.

First, no policy has been more beneficial at preventing medical malpractice cases than “I’m sorry” laws that allow providers to apologize for poor outcomes suffered by patients with those statements not being held against the clinician in later court proceedings. Check with your insurance carrier and state association regarding the status of “I’m Sorry” legislation and advice on patient communication before embarking down this path.

At last glance, 39 US states and territories have some form of legal protection for physicians who apologize to patients after an adverse event and additional states have legislation pending (Figure 4).6 Even in states which have not yet passed legislation preventing apologies from being used against providers, it is clear that an open dialogue between doctor and patient, even one in which the doctor provides empathy without an admission of an error, results in far fewer lawsuits being initiated.

The cover of your grievance communication policy book should include the following two statements that should always be a part of any dialogue between the distressed patient and the accountable doctor: “I regret that you have had a bad experience with your _____. Neither one of us expected you to have these problems. I regret this has happened to you” and “I am ultimately responsible for your care. I am going to delve deeper into this matter to fully understand how it happened. I am going to stay in touch with you and share all the information with you as soon as I learn how this occurred.”

From this point forward, any and all scheduled phone conversations need to occur weekly between the patient and doctor until the patient is satisfied with the efforts undertaken to remedy the injury. Patients want to be sure that action has been taken to prevent a repeat error with them and any other future patients. It is critical that the interaction is performed between parties physically seated at the same level and not substituted with the practice’s or insurance company’s attorney, an uninvolved practice partner, office manager, etc.

Furthermore, do not permit staff (e.g., front desk, technical support and managers) to discuss the situation with the involved patient (or any other patients inside or outside the office) except to say that “I’m not aware of the specific concerns you are having, but I know that Dr. _____ is going to discuss everything with you in the exam room.”

Following a principle of truthful but limited disclosure, expressing how “sorry you are that the negative outcome happened” without taking blame for the complication allows for a joint grieving process between the doctor and patient and the patient’s family members.

An explanation of what happened and what future treatment options exist to potentially remedy the problem are critical for expressing care and maintain the doctor-patient relationship.

Finally, inform the patient and their family how you plan to use what you learn from your patient’s experience to try to prevent others from having the same or a similar problem in the future with other patients.

Takeaways

Ultimately, the patient understands that the physician is human and imperfect, but they will not tolerate dishonesty. Establishing all of the protocols listed within are certainly effective measures in reducing malpractice litigation events; however, developing a trusted doctor-patient relationship with our patients that nurtures open communication has proven to be the best tool yet.

As much as what’s been discussed has helped reduce lawsuits, always consult with your malpractice carrier before expressing regret and implementing these policies.

Dr. Conley is the founder of Conley Eye Care in Huntington, NY. He obtained his Master of Jurisprudence at Loyola University Chicago School of Law and is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. He lectures nationally on topics such as glaucoma, nutraceutical science, dry eye disease, imaging advancements in eye care and medical malpractice. He is is a paid consultant for Guardion Health Sciences.