|

“We must all hang together—or assuredly we will hang separately,” Ben Franklin said at the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The renegade early optometrists proposing laws and liberties previously unheard of might very well have felt the same way. They knew the work of building a new profession would take collective effort and carry considerable risk, so the impetus to organize was strong.

While today’s optometrist looking for like-minded colleagues—be it for solidarity, education or just to shoot the breeze about contact lens sales—has an abundance of options, it wasn’t always so easy.

AOA: The Early “Rebels”

Imagine facing jail time for charging a fee for an eye exam. The concern was real for opticians in the late 1800s and early 1900s, as pressure from medicine and an early lack of state laws regulating the rights of opticians left little protection for ODs. This became a rallying cry for a national group that eventually became the American Optometric Association (AOA).

“It is the very conflict with ‘organized medicine’ that is still an issue today that was the catalyst for the initiation of the AOA,” says Kirsten Hebert of the AOA’s Archives and Museum of Optometry division. “Arguments over scope of practice and professional jurisdiction, distinction between professionals with ethical codes and codified, regulated licensing from commercial dealers and tradesmen, and the growing science and technology in the fields of optics, medicine and public health gave birth to the discipline and the practice of optometry.”

A major tipping point occurred in 1895, when New York optometrist Charles Prentice was threatened with a jail sentence for charging a fee for an eye exam.1 The charge of “practicing medicine without a license” was one frequently leveled at optometrists in many states at the time, Ms. Hebert said.

|

| Frederick Boger was a fierce proponent of organizing, and lobbied in the pages of The Optical Journal for readers to join the American Association of Opticians. |

One of the early pioneers who helped shape the AOA—along with its first president, Dr. Charles Lembke of New York—was Frederick Boger, the founding editor of The Optician and then The Optical Journal, both predecessors of Review of Optometry. Dr. Prentice, following his near arrest, met with Boger and other key optometric leaders, all of whom recognized the need for legislation to protect optometry and the public.1 They met in September 1895, a get-together which later led to the formation of the Optical Society of the State of New York, setting the stage for the AOA.1

Mr. Boger’s rallying cry for an organized group was frequently found on the pages of The Optical Journal: “Now for a National Association or an American Association of opticians!” Mr. Boger wrote in the March 1895 edition. “There has been no combined effort thus far to effect such an organization, but we propose now to do whatever we can to bring about such a thing.”2 He then threw down the gauntlet, saying, “an American Association covering the whole country is what is needed, and the men to run it should step forward and organize.”2 Within his editorials, he continued to press the issue, stressing the need for an organization and much face-to-face politicking with prominent opticians.

After the AOA’s 1898 founding, Mr. Boger was feeling triumphant. “Naturally,” he wrote, “The Optical Journal feels an unbounded but a pardonable pride in the achievement of this grand national organization. We have spent nights of thought and days of ceaseless work to bring this thing about.”

He later went on to become the first secretary of the AOA, which was initially called the American Association of Opticians, and then renamed the American Optical Association in 1910 before it officially became the AOA in 1919.

Mr. Boger also played a prominent role in the push for a national convention. “The opticians of the United States desire to unite together for the purpose of holding an annual convention to discuss methods and plans for the advancement of the sciences of optics and the exhibition of optical manufacturers,” he wrote in The Optical Journal.1

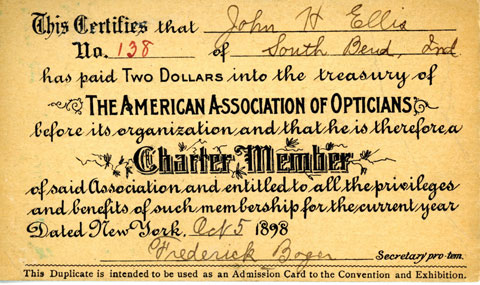

He continued to push an annual meeting, as he called on the membership to “unite together for the purpose of holding an annual convention to discuss methods and plans for the advancement of the science of optic and the exhibition of optical manufacturers.”3 Boger went so far as to publish applications for charter membership into the AOA in the magazine.1

|

| One of the first signed charter membership forms for the American Association of Opticians, complete with Frederick Boger’s signature. |

Mr. Boger also had a hand in making exhibit halls a standard, as it was his idea to include exhibits at the fledgling AOA’s first meeting, which helped elicit enough interest to attract a good attendance.1 While the first convention had no educational component, its exhibits included ophthalmometers, which had just come on the market, a collection of eyeglass guards, refractometers, eyeglasses, cameras and opera glasses.1

But the early AOA meetings didn’t come without challenges, particularly between two opposing member groups: dispensing and refracting opticians. There were “intense feelings of jealousy between the factions and great pains were necessary to keep the meeting harmonious,” Mr. Boger reported.1 This sentiment remained for several years until membership was limited to refracting opticians.1

While education is a given at most optometric meetings today, the AOA offered its first educational courses at the 1901 Chicago convention. This included 13 lectures on topics such as “Anatomy and Physiology of the Eye,” “The People We Meet in the Refracting Room,” “The Eyes of Domestic Animals,” “The Use of the Ophthalmometer” and “Optical Advertising.”1

Regional CE Meetings Keep it Close to HomeChances are that no matter where you live in the United States, you’re bound to find a regional CE meeting if the national ones have gotten too big and unruly for your taste. Over the last few decades, the growth of annual regional meetings have allowed ODs to earn CE credit in their own time zone—and comfort zone. Just some of the biggest players are the Great Western Council of Optometry, EastWest Eye, the Mountain West Council of Optometry and, of course, the Southeastern Congress of Optometry (SECO), which has national visibility, but retains a distinctly Southern feel. One of the earliest regional meetings, the Heart of America Contact Lens Society (HOACLS), began in the early 1960s with the goal of providing post-graduate education in the theory and application of contact lenses, says HOACLS president Craig Brawley, OD. The first meeting in 1962 featured 40 original members and three speakers renowned for their contact lens expertise. By the 1970s, HOACLS was getting recognition as the world’s largest meeting devoted to contact lenses, Dr. Brawley adds. In the 1980s, optometry was beginning to expand its scope of practice, and contact lenses became more innovative, he says. As such, HOACLS changed its program by adding primary care education to the meeting. Today, HOACLS attracts more than 1,200 attendees each year and supports optometry by giving back to the state associations, with $100,000 returned to the five member associations it represents, according to Dr. Brawley. HOACLS also returns funds to any state that has 25 or more doctors attending the meeting and provides scholarships for optometry students. |

By 1902, the structure of the AOA began to form, and at the mid-year meeting in Cleveland, a reorganization plan was laid out where a national association would become a federation of affiliated state associations, and a new plan for a House of Delegates selected by state associations was introduced.1

During the 1904 meeting, attendees battled over whether to accept the moniker “optometrist.” “Can any good come out of constant stirrings up of the sectional feelings between the various classes of opticians?” Mr. Boger wrote in the August 25, 1904 edition of the magazine. “The action of the Milwaukee Convention, wherein it expressed its approval of the word ‘optometrist,’ and urged its general use by opticians who refract, will surely be a large factor in the future progress of the Association.”4

The AOA’s first official “congress” was held in 1914 in St. Louis. While the AOA was gaining structure and membership, that meeting had a different set of challenges, mainly the heat. By now renamed The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry—or Optical Journal-Review for short—the magazine wrote in its pre-convention issues that “rooms with electric fans will be in demand at the hotels” and the Planter’s Hotel assured attendees that “each room has circulating ice water as well as a private bath.”4 Temperatures soared to 100 degrees during the congress, and at the annual banquet, men were encouraged to remove their dinner jackets if they were “wearing clean shirts.”5

The first congress sought to determine how the scope of optometry practice and the qualifications of practitioners should be defined and regulated.5 With this in mind, the AOA established committees dedicated to setting standards of practice, defining association positions, educating practitioners and the public about the profession, and working to consolidate optometrists under the wing of the association for the purpose of forwarding beneficial legislation.5

COPE: A History of Continuity for CEThese days, COPE credit is as essential as the subject matter being taught. COPE-approved CE is necessary for relicensure and has become a standard. But prior to COPE’s creation in 1993, individual licensing boards reviewed and approved continuing education courses, which often resulted in a confusing, non-standardized process. Pre-COPE, each state, regional and national CE provider had to send volumes of information to multiple jurisdictions.1 This increased costs to CE providers, and optometrists with multiple licenses were often confused as to the specific CE required for license renewal in each jurisdiction.1 The burden of proof was on the practitioner to contact each regulatory board to determine if a course would be acceptable.1 “It was an inconsistent, inefficient, and often confusing system,” says Jim Campbell, OD, current chair of the COPE Committee. In June 1991, a senior ASCO executive and member of the Board of Directors of the National Board of Examiners in Optometry (NBEO) addressed the annual House of Delegates of ARBO and challenged the licensing boards to assume a leadership role in improving the current competency standards of practitioners for licensure renewal. To address this challenge, ARBO established the Continuing Competency Assessment Committee (CCAC), comprised of representatives from ARBO, AOA, ASCO and the American Academy of Optometry. This led to the creation of COPE in 1993.1 “COPE accreditation standardized the process and reduced the amount of work for licensing boards, CE providers, and optometrists,” says Dr. Campbell. “Over time, CE requirements have changed with expanding scope of practice and demands for federal accountability. COPE standards have also evolved, with implementation of the Standards for Commercial support and adoption of accreditation criteria used by other health care professions, to meet the needs of a continuously changing environment.” More than 20 years since its formation, COPE continues to review thousands of courses per year. In 2015, COPE reviewed approximately 4,000 courses.

|

The scientific section, in particular, performed a critical function.5 By providing a forum for conducting and disseminating research and building a knowledge base, the section laid the foundation for the development of educational standards and best-practices, clinical guidelines and measures of competency.5

Thirty-plus years after the AOA was founded, The Optical Journal-Review reported the strides in the national organization, yet hurdles still existed from organized medicine. In the June 30, 1930 issue, the AOA president, George S. Houghton of Boston, wrote in his annual address, “Hardly a day passes that this office is not in receipt of information about our medical friends, or others, that have caused statements to be published which may appear as vitally detrimental to optometry.”6

|

| Frederick Boger, far left, gathers with other AOA members at an early meeting. |

Despite the annual meetings, some optometrists still felt more needed to be done to promote education. In an article entitled “A Call to the Colors,” published in the Feb. 15, 1934 edition of The Optical Journal-Review, Houston optometrist G. Henry Aronsfeld expressed the sheer necessity of annual meetings with a strong focus on research and education to ensure optometry’s future. “That our post-graduate work is at the present time in an abominable state of chaos and that this condition is disrupting and disorganizing optometry, must be manifest to all who view the matter from an objective and unbiased standpoint and who look a little deeper than ballyhoo and self-laudation when searching for ultimate results. That these regrettable conditions must remain so indefinitely is unthinkable,” Dr. Aronsfeld wrote.7

Fast forward to today. The AOA’s annual congress, now known as “Optometry’s Meeting,” has grown to attract thousands of ODs each year for the latest in clinical CE. But undoubtedly, those early pioneers who joined forces to promote and protect the profession set a foundation for what the AOA is today.

“The AOA gives members confidence they will have what they need for a thriving, successful future in optometry and the security the profession will be strong,” says current AOA president Steven Loomis, OD. “We are a force for public health, the leader for optometry, and a tireless advocate for the profession. We provide clinical tools and continuing education so members can be on the leading edge of patient care. I’m proud to be a part of an organization that has more than 100 years of representing doctors of optometry and am confident that we are poised for another century of being the association for the profession.”

AAO: An Eye on Research

In January 1922, nine optometrists and two medical doctors met in St. Louis and began an organization for optometric study in higher branches. In June of that same year, the American Academy of Optometry (AAO) was officially organized with the goal to raise the standards of optometric practice, education and ethics. But in some ways, the AAO had its earliest beginnings in 1898 when the American Association of Opticians was formed.8 That first national organization brought together members of the profession to improve optometry, and raising educational and scientific standards was also high on the priority list.8The first attempt at creating an Academy was made in 1901 at the AOA meeting in Chicago, when then President A.J. Cross proposed the establishment of an optical college, essentially a “paper college” that would give exams in various subjects. While this didn’t gain steam, the AOA created a physiological branch that made up the educational program of the association for the next two decades.

On Nov. 15, 1905, E. LeRoy Ryer, president of the Optical Society of the City of New York, addressed a meeting of the group and proposed the establishment of an American Academy of Optometry with the fundamental idea being certification.1 Ryer asked if there was an existing organization that “does justice to the superior class of intelligence.” He further wonders, “have we any that offers sufficient rewards to warrant men striving to attain membership, have we any that draw a real distinction between the well and poorly educated?”1 A year later in 1906, AOA President John Ellis addressed the Indiana Optometric Association and strongly favored the formation of the Academy.1

The idea of an academy had its share of proponents, but others were strongly against the creation of one, thinking it would be a haven for snobby elitists.

A.J. Stoessel, president of the Wisconsin Association of Optometrists, wrote in The Optometric Journal: “I shall give you a few of the many reasons why I do not consider an organization like the proposed American Academy of Optometry advisable. In doing so, I know that an awful fate awaits me, since Mr. LeRoy Ryer, with most magnificent audacity, disposes of any intended criticism of his pet scheme beforehand by classing his critics as ‘shallow minds, afraid to be separated from the really deep minds.’ Now, is it not fact that men who mistake ‘their superficial knowledge for real knowledge’ are just the ones that are forever striving to band themselves in select societies and have that holier than thou feeling that the possession of a membership certification gives them?”9

It took nearly two decades more for the AAO to be formed. In the book, The History of the American Academy of Optometry 1987-2010, this early group of founders was described as having limited resources, “but their ideals were visionary: they wanted to foster optometric research, education and clinical excellence.”10

The first annual meeting of the AAO was held in December 1922 with presentation of papers, business sections and election of officers. By December 1929, the membership passed the 100 mark, and attendance at the annual meeting was becoming large enough to attract the attention of scientists as a place to present results of research.8 In 1930, the first research fellowship was established at Columbia University, and in December 1940, examinations for membership in the academy was given to more than 60 applicants during the annual meeting. This was the first time an achievement test was required and an instruction manual had been prepared for guidance for applications.8

In 1947, the American Optometric Foundation (AOF) was created through the vision of William C. Ezell, OD. As the immediate past-president of the AOA, Dr. Ezell along with six other prominent optometrists enlisted the support of the profession to contribute to the creation of “a foundation to uphold, broaden, foster, promote and aid optometric education, the optometric profession and its practitioners.”

The idea of a separate program for short clinical courses immediately prior to the annual meeting was approved by the Academy’s executive council in 1950, and by the 1955 meeting, postgraduate courses were first presented in Chicago with 41 instructors present.

Today, the AAO achieved its largest attendance in history at the Academy 2015 meeting—7,489 total registrants—an 18% increase over 2014 attendance. This included a record 1,400 student attendees—an increase of 40% over 2014. The surge in student attendees at Academy 2015 New Orleans was not a fluke, as six years earlier, the AAO created a program to help students early in their careers.

SECO: A Tradition of CE in the South

The first SECO Congress was held in 1924 in Greenville, SC, where an estimated 100 optometrists attended a meeting and tradeshow. SECO started as a loosely knit organization, with no official ties to organized optometry—it was simply an annual educational meeting.11

Optometrists from 13 states and one jurisdiction comprised the original grouping: Alabama, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia.

While the congress became a staple for ODs through the years, as scope of practice laws began to change in the 1970s, SECO’s courses expanded to provide professional development in the new arena of diagnostic pharmaceuticals. The profession’s strategy of “educate, then legislate” created a need to prepare practitioners for a whole new level of patient care and SECO stepped in to provide this.11

Today’s annual congress held in Atlanta is a mainstay of the large optometric meetings and generally features more than 400 courses and 170 CE credit hours.

From OptiFair to Expo

Optometry conferences traditionally focused on education and politics, with exhibits being a part of the event but not central to it. That changed in 1978 when Irving Bennett, OD, launched the OptiFair, a meeting that gave products due prominence along with education. In 1986, OptiFair morphed into Vision Expo. The year prior, leaders from the Vision Council & Reed Exhibitions (formerly Vision Industry Council of America and Cahners Exposition Group, respectively) signed an agreement to jointly acquire the OptiFair trade show. In 1988, Vision Expo expanded by acquiring the Better Vision Institute to encourage more frequent eye exams.

OptiFair: The First US Optometric Trade ShowBy Irving Bennett, OD Probably the most important day of my non-practice business life happened in the spring of 1977 when Advisory Enterprises, the publishing firm I headed, held a gathering of optical/ophthalmic leaders. More than 100 manufacturers and distributors gathered at New York City’s prestigious Plaza Hotel. The speaker was a statistician from Washington, DC who had just published detailed data on the optometric profession and the optical industry. The report stated that the optical part of the industry generated about $6 billion dollars in sales and that it had to do things differently to stimulate growth. My lack of due diligence on hiring a speaker, sight unseen, was soon evident. He had the data all right, but his presentation was dry and boring—very boring. As master of ceremonies, I knew I had to do something. When the speaker paused to make a point about 40 minutes in, I stood up and said, “Thank you so very much for that inspiring speech.” And I started to applaud. The audience, though surprised, followed suit. “You have heard the data and our need to do something to stimulate more eye examinations and more eyewear sales,” I said, adding “why not a show in Madison Square Garden for optometrists, ophthalmologists, opticians and for you to display your products?” The applause was spontaneous and enthusiastic. That was the day OptiFair was born. The first OptiFair, held on March 3, 1978, was a booming success. We had promised exhibitors we would attract more than 5,000 professionals to the show—not counting anyone not involved in the professions. No optometric convention before had ever approached 5,000 attendees. We had 6,511. In the words of one exhibitor, and echoed by many, the atmosphere was “electric.” We had 30 OptiFairs in all and our attendance numbers in New York topped 10,000 at our last OptiFair. But the principals at Advisory had accomplished what they set out to do, and it was time to sit back and smell the roses. We sold our publishing/meeting company in 1987. It was a great run. OptiFair changed how meetings were conducted for optometrists and opticians. Ophthalmic meetings usually had only two or three, maybe four, lecturers with good reputations. OptiFairs used at least 50 lecturers per show, giving many aspiring speakers a chance before a national audience. We “discovered” many gems, and many OptiFair alumni are still on the lecture circuit. We provided free registration, making it easy for “non-members” to visit the exhibits. We gave every registrant a white badge, not segregating professionals with different colored badges. We were one big community, not several smaller ones. We gave ophthalmic techs the opportunity to have a meeting with a selection of courses to help them do their jobs better. OptiFair was one of only a few opportunities for ancillary personnel in professional offices to get thorough education. We incorporated workshops as educational vehicles. We encouraged exhibitors to provide special no-charge “Exhibitor Seminars,” and we suggested larger exhibitors provide out-of-the hotel events, such as an evening at the Radio City Musical Hall or a cruise in New York Harbor to maximize their contact with customers. |

Now celebrating its 30th anniversary with two annual meetings, Vision Expo East in New York City and Vision Expo West in Las Vegas, Vision Expo has expanded in recent years from being a frame show to a heavy hitter in the clinical CE arena.

In an effort to provide more relevant clinical content and educational opportunities for the entire office, Vision Expo added veteran optometrist Kirk Smick, OD, to join its conference advisory board in 2007, a Vision Expo spokeswoman said. Today, VEW recruits new members to the advisory board who specialize in key educational areas of the profession, she added.

Total attendees each year average roughly 30,000. Each meeting also includes some 320+ hours of education, according to Vision Expo.

Today, optometrists have assured their standing as vital contributors to the American health care system and have more CE meetings to choose from than ever before, thanks to those early pioneers who paved the way for the evolution of the profession. Bifocal inventor Ben Franklin would be proud!

|

1. Gregg JR. American Optometric Association, A History. American Optometric Association. 1972:3,7-10,20. 2. Optical Journal. March 15, 1895:13. 3. Optical Journal and Review of Optometry. May 15, 1947:52. 4. Optical Journal. August 25, 1904;14:525. 5. www.aoa.org/about-the-aoa/archives-and-museum/exhibits/the-congress-of-1914?sso=y. 6. Optical Journal. June 30, 1930:24. 7. Aronsfeld GH. A Call to the Colors. The Optical Journal-Review. Feb. 15, 1934:20-21. 8. Gregg JR. History of the American Academy of Optometry 1922-1986. American Academy of Optometry. 1987-2010:3,5,7. 9. Stoessel SJ. Against the Optometrical Academy. Opt J. March 1, 1906;17(10):401. 10. Newcomb RD, Eger M. History of the American Academy of Optometry 1987-2010. 15. 11. www.secointernational.com/about-us/history.html. |