|

In August 2019, a 72-year-old Caucasian male presented as a new patient for continuation of care. Given that my practice is located in an area with a large influx of retirees, it’s fairly common to pick up existing glaucoma patients. This particular patient had been diagnosed with glaucoma in both eyes in 1995. He was initially medicated with a series of drops that ultimately did not effectively reduce his intraocular pressure (IOP). He ended up having surgery in both eyes for his glaucoma.

The patient also had bilateral cataract surgery in 2003 and a retinal detachment repair in the left eye in 2005. From what I could determine, he had not taken topical or oral medications for his glaucoma since the cataract surgery, except for a short dose in the left eye following the retinal detachment repair. He reported that he performs daily ocular massages OU, as directed by his previous provider.

|

|

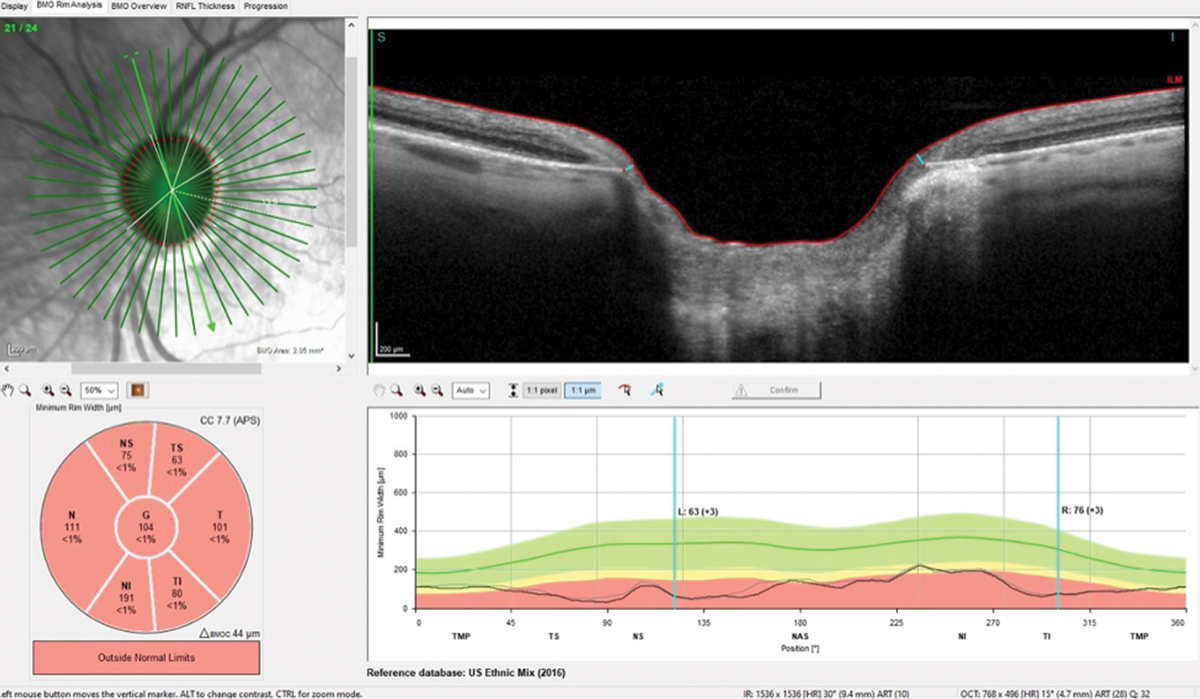

Note the exceedingly thin neuroretinal rim, especially in the temporal portion of the optic nerve, consistent with advanced damage OS. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnostics

The patient’s best-corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) were 20/40- OD and 20/150 OS. His pupils were round and reactive to light, and there was no frank pupillary defect noted in either eye.

Slit lamp examination of the anterior segments was remarkable for bilateral dermatochalasis. The patient’s anterior segment evaluation further demonstrated bilateral trabeculectomies and surgical peripheral iridotomies.

The blebs were well-formed and not aberrant in any visible way. The corneas were clear, as were the anterior chambers. The angles were open, as the patient was pseudophakic. His intraocular lenses were well-centered OU.

The patient’s applanation tensions were 20mm Hg OD and 21mm Hg OS at 10:15am. His pachymetry readings were 552µm OD and 497µm OS.

Through dilated pupils, the patient’s cup-to-disc ratios were 0.65x0.75 OD and 0.85x0.90 OS. The neuroretinal rims were thinned, especially in the left eye, and consistent with advanced glaucomatous optic neuropathy OS. They were well-perfused and not pale, and both discs were on the larger size.

|

|

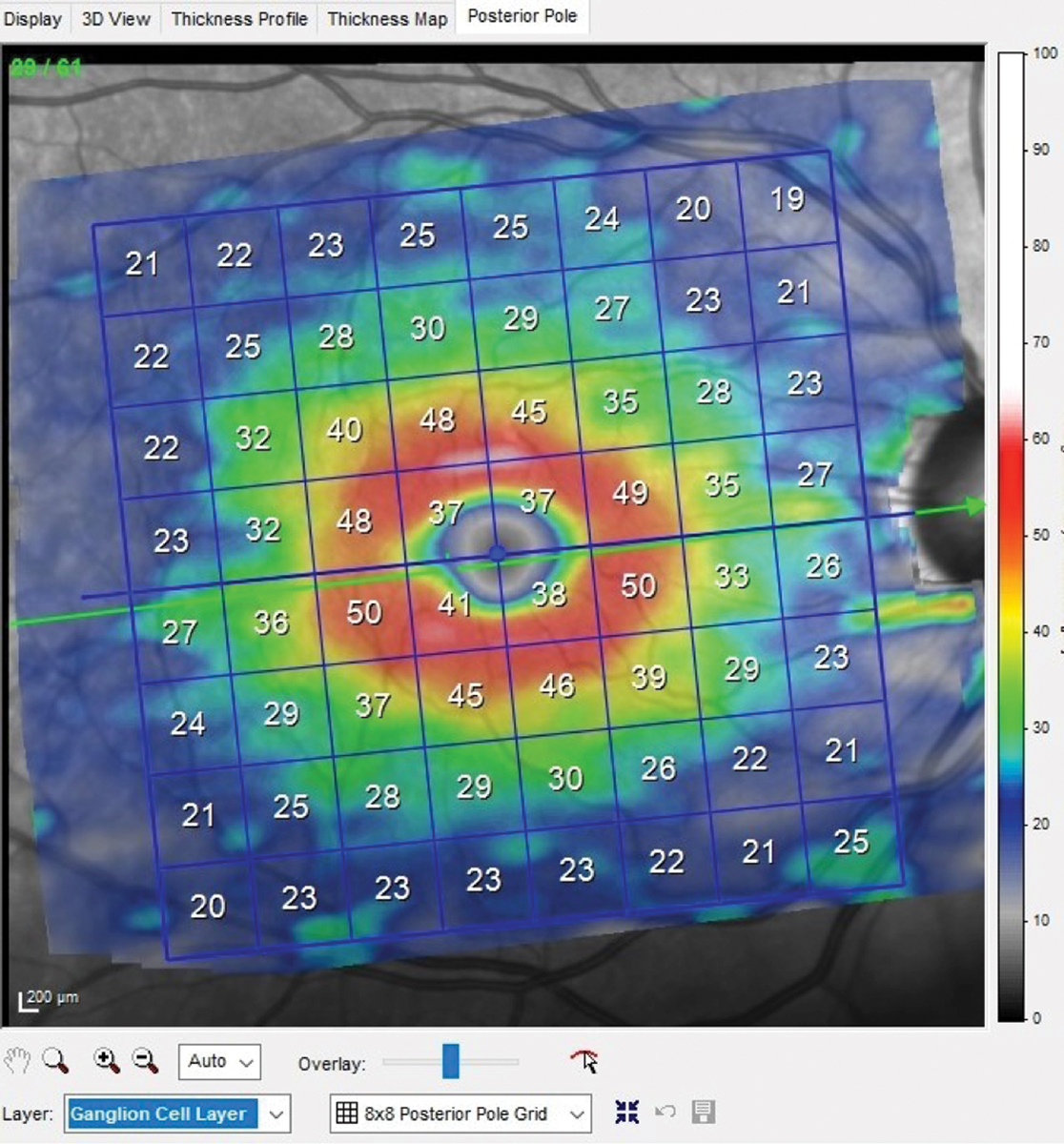

OCT of the right eye shows a relatively normal macular ganglion cell layer. Ganglion cell layer thickness averages 40µm to 45µm in the macular region, with the thickest region adjacent to the foveal avascular zone. Click image to enlarge. |

The patient’s macular evaluation was characterized by retinal pigmented epithelium disruption OS>OD and fine drusen OU. There was no evidence of angiogenic age-related macular degeneration in either eye. He had an epiretinal membrane in the left eye.

The patient’s vascular evaluation was essentially normal despite mild age-related arteriolar sclerosis OU. His peripheral retinal evaluation OD was normal; the left was characterized by an encircling scleral buckle. There were no new holes, tears or traction noted in either eye.

Discussion

The more advanced the glaucoma, the quicker it can progress. These patients need to be watched more closely, and therapy changes should be expected. Initial visits with a new patient without records make it impossible to determine disease stability. The only indication I had about this patient’s stability at his first visit was that his previous provider was comfortable enough to see him on a six-month basis.

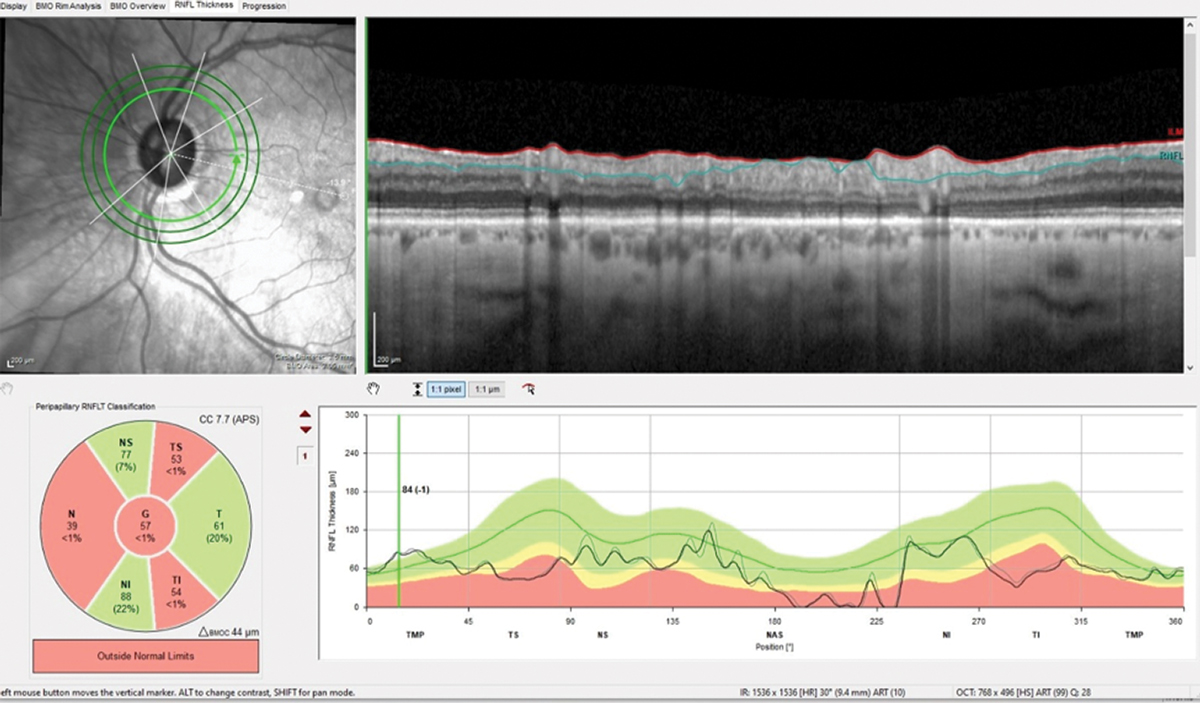

I was eventually able to obtain a copy of the patient’s previous records, which contained optical coherence tomography (OCT) printouts. The previous provider’s OCT device was different than mine, but the images demonstrated similar disease states compared with my findings. While I was not able to compare data points across both devices to the precision I would have liked, I was able to fill in an important piece of the glaucoma puzzle: this patient has had advanced disease OS for quite some time.

Given that I was not certain of his stability, I saw the patient back in two months, at which point his IOPs were 15mm Hg OD and 14mm Hg OS.

During the next few visits, no disc hemorrhages were noted. The blebs remained patent and well-formed. The OCTs remained stable, as did the visual fields. The patient’s IOPs averaged in the mid-teens, OD and OS. However, in July 2020, the patient’s IOPs were 26mm Hg OD and 13mm Hg OS.

At his next visit in September 2020, the patient’s IOPs again fell into his historical range. OCT demonstrated no significant change in the neuroretinal rim, perioptic retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) or macular scans. His BCVAs were the same as his initial visit.

|

|

The 3.50mm diameter RNFL scan demonstrates classic superotemporal and inferotemporal RNFL thinning in the left eye. Note the lack of change from baseline (gray). Click image to enlarge. |

The patient’s visual fields and OCTs were stable over the first year that I saw him, but his IOPs were the wild card. This is not surprising, as his method of IOP control included bilateral trabeculectomies and digital massages. Digital massaging is somewhat of a double-edged sword; with a well-formed bleb, it lowers IOP, but there are significant differences from patient to patient as to how long the IOP remains depressed. Also, during digital massage, IOP is artificially elevated for short periods of time, so too much pressure can be detrimental.

Structurally and functionally, the patient showed no indication of progression, so we decided on follow-ups every six months.

Advanced disease progresses much faster than mild disease, which has a built-in safety net with adequate remaining neuroretinal rim tissue. In both cases, though, the patient needs to be watched closely for structural or functional change. The specifics of visit timing, different testing and IOP-lowering often take time to flesh out, especially with patients who are new to your practice.