|

An 88-year-old man presented with a mildly red and irritated left eye. He had a previous history of dry eye syndrome for which he used Cequa (cyclosporine 0.09%, Sun Pharma) BID OU. His uncorrected acuity was 20/30 OD and 20/25 OS. Neuro-ocular screening was normal in each eye. His right eye was normal, but he manifested a paracentral dendritic lesion on his left cornea along with a grade 1 conjunctival injection and an accumulation of endothelial inflammatory cells. There were rare cells and mild flare in his left anterior chamber. His intraocular pressure was 11mm Hg OD and 12mm Hg OS. Corneal sensitivity testing revealed a subjective decrease of 20% in his left eye.

His medical record revealed that he had a previous episode of dendritic keratitis followed by a prolonged course of diffuse epitheliopathy and corneal non-healing approximately two years earlier with another practitioner in the practice. He was diagnosed with herpes simplex dendritic keratitis and prescribed Valtrex (oral valacyclovir, GlaxoSmithKline) 1000mg BID and Zirgan (topical ganciclovir ointment, Bausch + Lomb) five times daily OS.

He was told to continue his Cequa as prescribed and to be seen in one week. While the diagnosis and initial management was straightforward, his history of epitheliopathy and prolonged corneal healing was somewhat troubling.

|

|

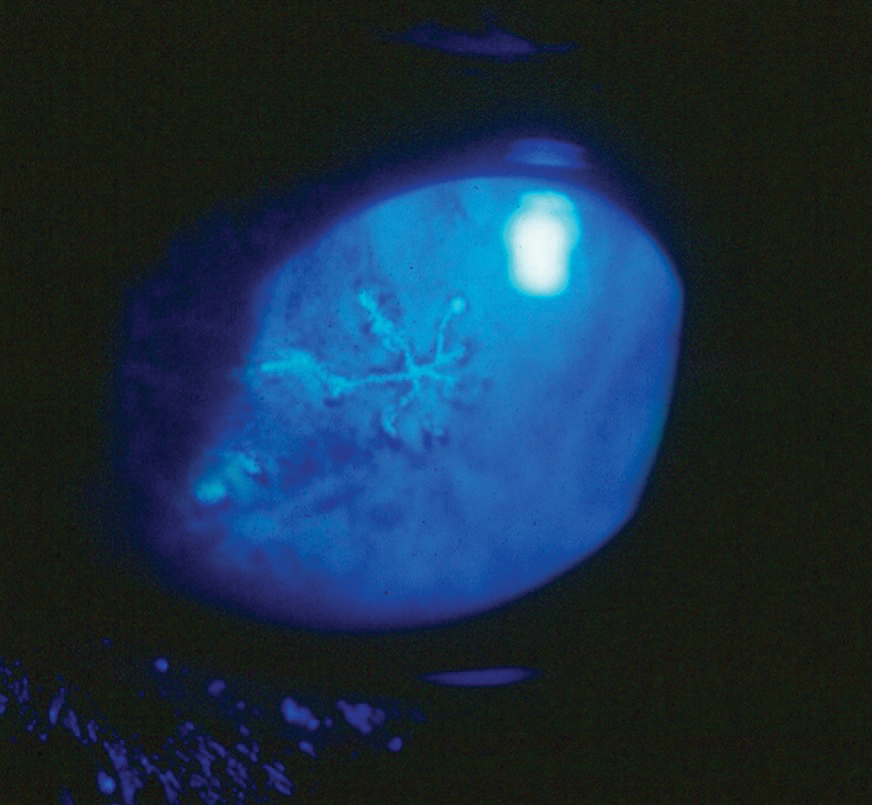

The herpes simplex dendrite is a hallmark finding in HSV keratitis. Click image to enlarge. |

A Latent Infection

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a common pathogen and frequent source of ocular infection. Nearly 60% of the American population is seropositive for HSV-1, and another 17% is seropositive for HSV-2.1 Initial ocular infection by HSV tends to be seen in younger patients at an average age of 24.1,2

Recurrence of HSV has been associated with causative factors that include fever, hormonal changes, ultraviolet sun exposure, psychological stress, ocular trauma, trigeminal nerve manipulation, steroid use, ocular surgery, exposure to ultraviolet radiation, immunosuppressive agents and glaucoma treatment with prostaglandin analogs.3-5

Epithelial dendritic keratitis is the second most common ocular manifestation of HSV, occurring in 12.2% of cases overall, while stromal keratitis was more prevalent at 25.4%.6,7 HSV epithelial keratitis presents as a unilateral red eye with a variable degree of pain or irritation. Vision may or may not be affected, depending upon the location and extent of the corneal lesion. Bilateral HSV keratitis may be encountered in a small percentage of cases, though it is more common in children and those with immune or atopic disease.8,9

The hallmark finding in HSV keratitis involves a dendritic ulceration of the corneal epithelium, which may be accompanied by a stromal keratitis in more severe presentations. Secondary anterior uveitis is often encountered with the keratitis, particularly when treatment is delayed.7 Other epithelial manifestations include geographic ulcers, marginal ulcers, neurotrophic ulcers and diffuse epitheliopathy.

HSV keratitis can be caused by either type 1 or 2 herpes simplex.10 The virus is transmitted via bodily fluids and affects the skin and mucous membranes of the infected host.1 Primary herpetic infections are generally encountered in children and young adults.1,2 HSV establishes what is known as a lytic and latent infection.11 Latent reactivation occurs intermittently and chronically—a life-long source of recurrent infection. After resolution of the initial infection, the herpes virus migrates along local nerves to regional ganglia and remains dormant until reactivated by specific stimuli.12 On average, patients experience recurrences at a rate of 0.6 episodes per year.13

While many of the ocular manifestations related to HSV are immune (e.g., delayed hypersensitivity reaction) or inflammatory in nature (e.g., stromal and disciform keratitis, iridocyclitis), epithelial keratitis represents infection by live virus.14,15 Viral replication in most cases is confined to the corneal epithelium, with stromal invasion impeded by early-responding, non-specific defense mechanisms.11,15

Treatment

Manage HSV epithelial keratitis quickly and aggressively to prevent penetration into deeper corneal tissues with subsequent scarring and vision loss. The treatment of choice consists of topical and oral antiviral therapies. Historically, Viroptic (trifluridine 1%, Monarch) has been the standard treatment. The initial dosage of trifluridine is one drop every two hours up to nine times daily for HSV epithelial keratitis; as regression of the dendrite ensues, the dosage may be tapered to Q3H to Q4H until complete resolution is seen, over a period of seven to 10 days.16,17

Zirgan, an alternative to cornea-toxic trifluridine, requires less frequent initial dosing at just five times daily until the corneal ulcer heals and then three times per day for another seven days. Ganciclovir demonstrates greatly reduced corneal toxicity as compared with trifluridine because it is only taken up by virus-infected cells.14,18 Cycloplegia may be initiated, depending upon the severity of the uveitic response and the patient’s subjective discomfort.

Oral antiviral agents can also effectively treat HSV epithelial keratitis, generating pharmacotherapeutic levels in the tears.19-21 Management options for HSV epithelial keratitis include acyclovir 200mg to 400mg five times daily, valacyclovir 500mg to 1000mg three times daily and famciclovir 250mg to 500mg two to three times daily for 21 days. The Acyclovir Prevention Trial (APT of the HEDS II) demonstrated that oral antiviral medications may further serve a preventative role by reducing the frequency and severity of recurrent infective outbreaks.22 Acyclovir 400mg BID is the most commonly used regimen for prophylactic suppression, but valacyclovir 500mg once daily may also be used.23

Judicious topical steroid use can be a beneficial adjunct when used under the umbrella of a topical or oral antiviral agents, following several days of effective antiviral therapy; this is particularly true in cases of associated stromal inflammation.24

When managed appropriately, HSV epithelial keratitis resolves without scarring, although there is potential with recurrent disease to develop neurotrophism and persistent epithelial non-healing.25 In such cases, amniotic membranes may assist with returning the eye to normal homeostasis.26-28 Autologous serum can also be beneficial in promoting corneal healing.29,30 Blood serum contains many growth factors, and autologous serum eye drops are useful in corneal re-epithelialization when a patient’s serum is diluted by 20% or 50% to create the eye drops and used every three hours daily.31

Follow-Up

When the patient returned one week later, his right eye was unchanged, but his acuity had dropped to counting fingers at two feet in his left. The dendritic pattern was now gone, but there was dense, diffuse corneal epitheliopathy across the entire cornea, similar to the course he had previously. There was still a significant endothelialitis present. To reduce toxicity issues, topical ganciclovir was discontinued while the oral valacyclovir was continued. He was prescribed a topical steroid-antibiotic (tobramycin-dexamethasone) combination QID OS. An amniotic membrane was placed on his eye.

Upon his last follow-up eight weeks after his initial presentation, his ocular inflammation resolved on topical steroids, which had been discontinued as had the valacyclovir, and he reported a great improvement in all findings though he was still on gabapentin for post-herpetic neuralgia.

Dr. Sowka is an attending optometric physician at Center for Sight in Sarasota, FL, where he focuses on glaucoma management and neuro-ophthalmic disease. He is a consultant and advisory board member for Carl Zeiss Meditec and Bausch Health.

1. Gurwood AS, Savochka J, Sirgany BJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Optometry. 2002;73(5):295-302. 2. McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(1):1-14. 3. Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ III, Kurland LT, et al. Population-based study of herpes zoster and its sequelae. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982; 61:310-6. 4. Karbassi M, Raizman MB, Schuman JS. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1992;36(6):395-10. 5. Cobo M, Foulks GN, Liesegang TJ, et al. Observations on the natural history of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6(1):195-9. 6. Burgoon CF, Burgoon JS, Baldridge GD. The natural history of herpes zoster. J Am Med Assoc.1957;164(3):265-9. 7. Arvin AM. Investigations of the pathogenesis of Varicella zoster virus infection in the SCIDhu mouse model. Herpes. 2006;13(3):75-80. 8. Carreño A, López-Herce J, Verdú A, et al. Varicella encephalopathy in immunocompetent children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(3):193-5. 9. Heininger U, Seward JF. Varicella. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1365-76. 10. Boeckh M. Prevention of VZV infection in immunosuppressed patients using antiviral agents. Herpes. 2006;13(3):60-5. 11. No author listed. Chickenpox, pregnancy, and the newborn. Drug Ther Bull. 2005;43(9):69-72. 12. Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D. Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(8):2437-48. 13. Martin JB. Viral encephalitis and prion diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al. eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, (14th ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998;1023-31. 14. Schmader K. Herpes Zoster. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):ITC19-31. 15. Saguil A, Kane S, Mercado M, Lauters R. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia: prevention and management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(10):656-63. |