Although the prevalence and incidence of dry eye disease (DED) varies widely due to a lack of standardized testing and criteria, a recent report estimates more than 16 million adults in the United States are diagnosed with DED.1 Dry eye accounts for almost 25% of medical eye care visits and has been estimated to cost the US healthcare system $3.84 billion annually—this number increases to $55.4 billion when considering societal costs.2-4 While optometrists are fortunate to have an expanding armamentarium, artificial tears remain an integral part of the basic management strategy as a recommended first-line option.5-7 Although they do not directly address the underlying etiology of dry eye, artificial tears can effectively control symptoms and may be the primary therapeutic component for many with mild or episodic dry eye.8

Here, we review the most common commercially available artificial tears, the FDA-approved ingredients they use and the factors to consider when making treatment decisions and recommendations.

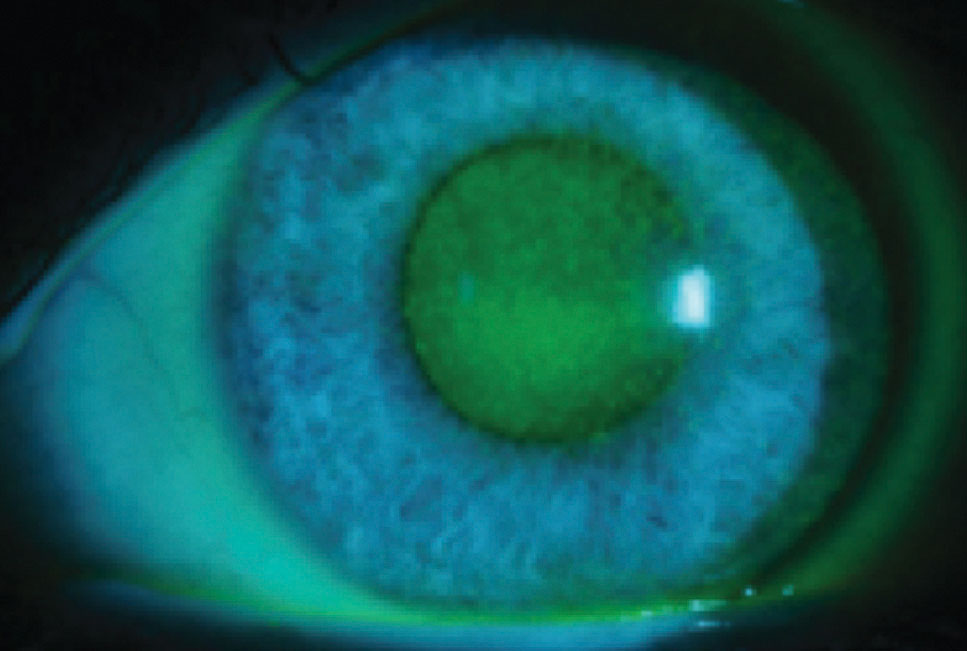

|

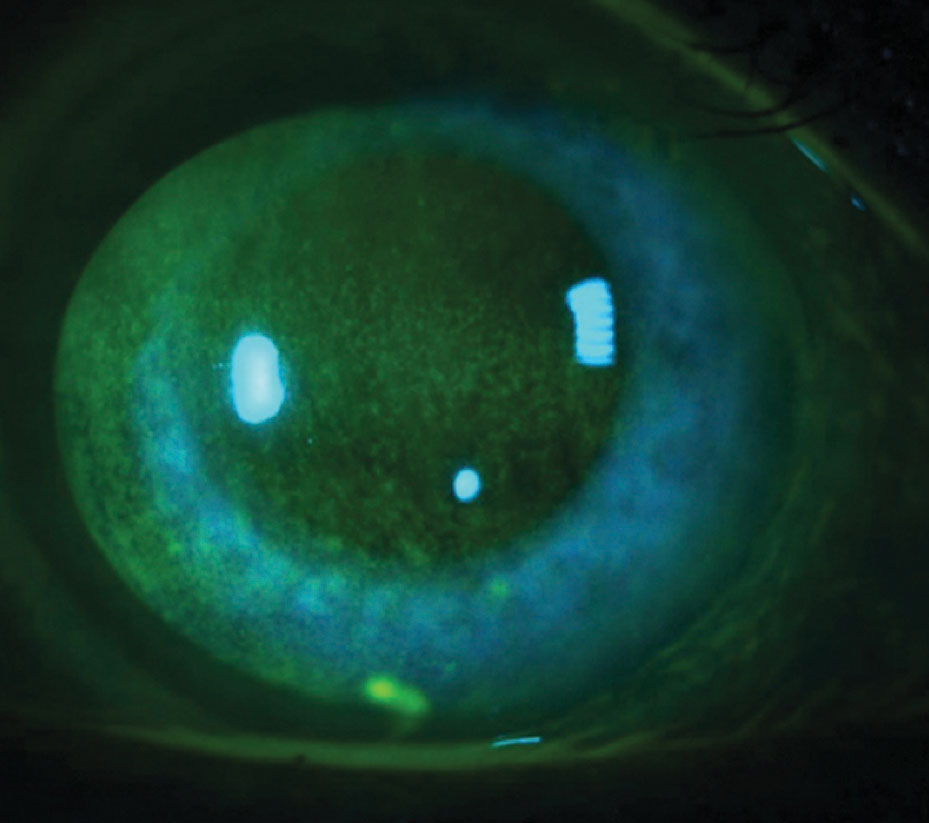

| This patient has chemical toxicity secondary to multiple topical antimicrobial medications. Clinicians should avoid iatrogenic DED by considering all concurrent ocular drops before recommending a preserved artificial tear. Photo by Christine W. Sindt, OD |

Approving Agents

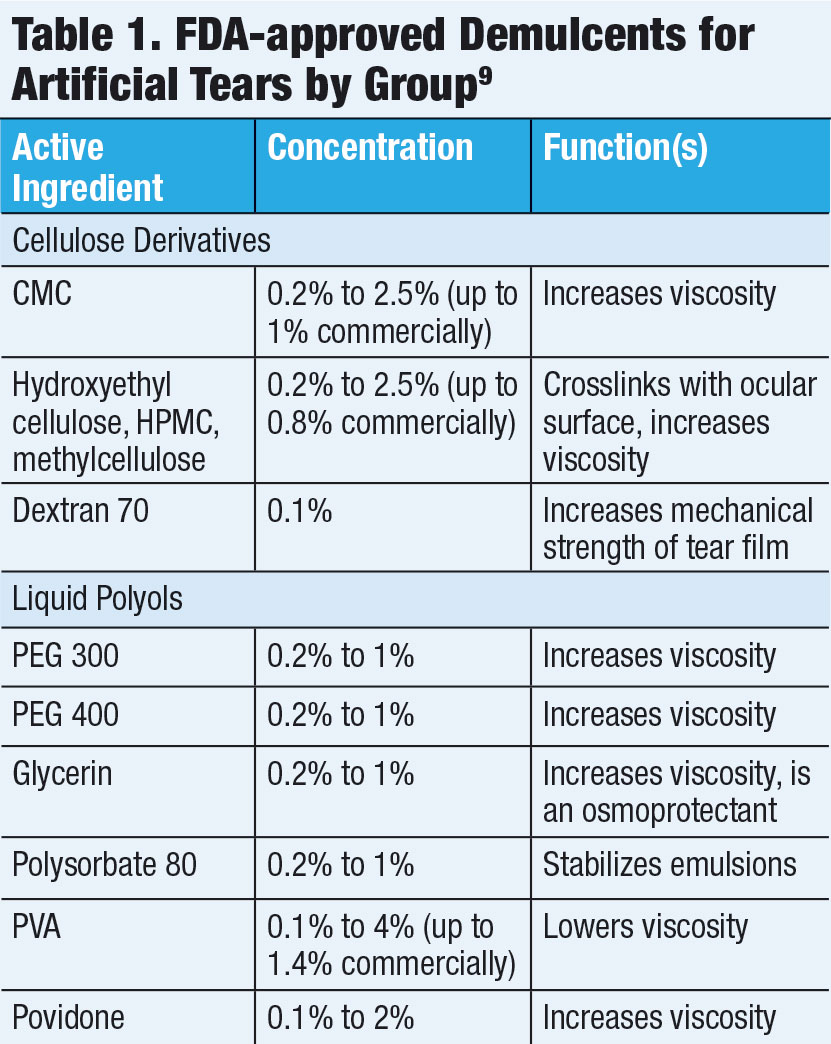

The FDA provides guidelines to facilitate and streamline the artificial tear approval process. The monograph includes approved active ingredients and concentrations, specific labeling requirements and good manufacturing processes (Table 1).

The primary active ingredients found in most artificial tears are either ophthalmic demulcents or emollients.

Demulcents are substances that soothe mucous membranes and, in the case of artificial tears, provide lubrication in the form of a mucoprotective film. They can alleviate discomfort, aid in water retention and decrease friction across the ocular surface. The FDA has established six categories of ophthalmic demulcents that must fall within a specified range of concentrations: cellulose derivatives, dextran 70, gelatin, liquid polyols, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and povidone. These products can be used alone or in combinations of up to three.9

One of the most commonly used demulcents is carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), a cellulose derivative. CMC increases the viscosity of tears and has mucoadhesive properties that allow it to remain on the ocular surface for long periods of time.10 The commercially available artificial tear concentration can range from 0.2% to 1%.9 The increased viscosity of higher concentrations can cause transient blur and eyelid debris, which is why these artificial tears should only be applied at night and to treat more severe DED. Another commonly used cellulose derivative is hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), or hypromellose. HPMC increases viscosity by crosslinking after contact with the ocular surface. Cellulose derivatives are found in products like Refresh Tears (Allergan), GenTeal Tears (Alcon) and TheraTears (Akorn).

Dextran 70 must be combined with another demulcent due to the compound’s low viscosity.9 This ingredient increases the mechanical strength of the tear film.

PVA, one of the oldest demulcents, lowers a solution’s viscosity. It is no longer found frequently in branded artificial tears due to the availability of more effective ingredients. Povidone, a water-soluble synthetic polymer, is also used in products like Betadine (Purdue Pharma) due to its antiseptic properties when combined with iodine. Povidone and PVA are found in drops like Refresh Classic (Allergan), FreshKote (Eyevance Pharmaceuticals) and Murine (Care Pharmaceuticals).

Other demulcents include liquid polyols, such as propylene glycol (PPG), polyethylene glycol (PEG) and glycerin. These increase viscosity by forming a mucoprotective layer and are found in Systane (Alcon), Blink (Johnson & Johnson Vision) and Soothe (Bausch + Lomb). Glycerin is used in Oasis (Oasis Medical) and Refresh Optive (Allergan).

Polysorbate 80 is included in eye drops to aid in the emulsification of formulations with oil, such as Soothe XP (Bausch + Lomb) and Refresh Optive Mega-3 (Allergan). The latter includes polysorbate 80, glycerin 1% and castor oil, all of which are inactive ingredients in Restasis (Allergan).

|

Emollients, such as fats or oils, increase the lipid layer thickness of the tear film, stabilize the tear film and reduce evaporation. More artificial tears containing lipids are becoming available due to an increased awareness of the role meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) plays in DED.11 Emollients, found in ointments and lipid-based tears, typically use a combination of mineral oil, light mineral oil and white petrolatum.

Artificial tears that contain lipids must be formulated as an emulsion, which can be classified based on the size of the oil droplet it contains: macroemulsions (larger than 100nm), nanoemulsions (10nm to 100nm), microemulsions (less than 10nm). Both the particle size and lipid concentration can affect visual blur on instillation. Manufacturers employ various methods to enhance emulsion stability, increase even spreading, enhance bioavailability of active ingredients and reduce unwanted side effects. Current lipid-based artificial tears include Systane Balance and Systane Complete (mineral oil, Alcon), Refresh Optive Advanced (castor oil, Allergan) and Refresh Optive Mega-3 (castor oil and flaxseed oil), Soothe XP (mineral oil and light mineral oil) and Retaine MGD (mineral oil and light mineral oil, Ocusoft). With the exceptions of Refresh Optive Advanced and Refresh Optive Mega-3, most lipid-based artificial tears require shaking prior to use to ensure a uniform concentration.

While more research needs to compare artificial tears with and without lipids in patients with MGD and DED, several studies have found that lipid-based drops improve dry eye symptoms.12-15

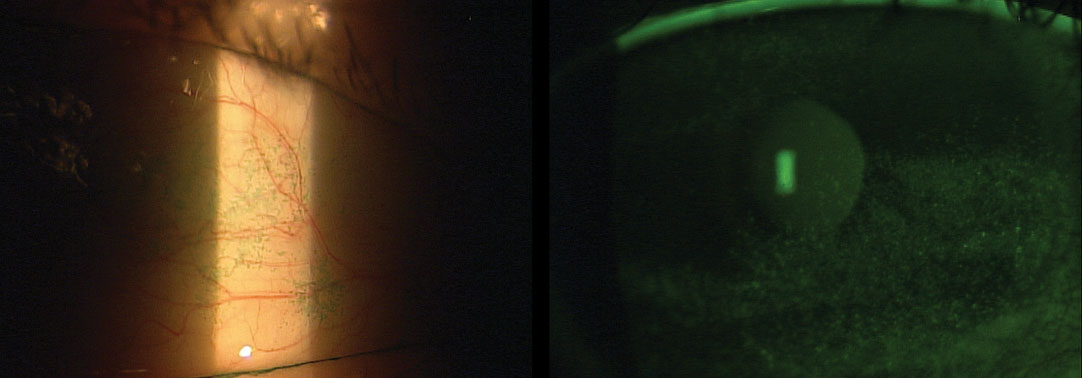

|

| NaFl corneal staining (left) and lissamine green conjunctival staining (right) significantly correlate when diagnosing DED. Patients at each stage of disease severity may benefit from artificial tear substitutes. Photos by Jason Miller, OD. |

Gray Areas

Inactive ingredients are not specified in the FDA’s ophthalmic monograph, but the guidelines state that ingredients must be suitable and safe and cannot interfere with a product’s effectiveness.16 The FDA maintains a vast list of approved inactive ingredients that may function as buffers, electrolytes, emulsifiers, osmoprotectants or viscosity-enhancers. These ingredients set individual drops apart from one another.

Buffers and electrolytes can adjust the pH and osmolarity of artificial tears. Many studies have looked into the association between tear film osmolarity and DED, which was highlighted in the TFOS DEWS report.17 Research shows a reduction in tear osmolarity correlates with reduced dry eye symptoms in patients treated with artificial tears.18 Although artificial tear osmolarity is not widely reported, TheraTears, a hypo-osmolar drop with an osmolarity well below that of other artificial tears, may relieve patients of their dry eye symptoms.19,20

Trehalose, an osmoprotectant found in Refresh Optive Mega-3 and TheraTears Extra, stabilizes cell membrane lipids and proteins and can protect corneal epithelial cells from death by desiccation.21

Sodium hyaluronate, a glycosaminoglycan, is added to drops like Blink and Oasis to increase lubrication and enhance viscosity. Refresh Optive Repair (Allergan) is a new option, the first in the United States to contain both CMC and sodium hyaluronate.22

Another unique inactive ingredient is hydroxypropyl-guar (HP-guar), a polymetric thickener that acts as a gelling agent in the Systane line of artificial tears. HP-guar combines with the two demulcents in Systane to form a low viscosity gel that activates as it interacts with the ocular surface and the pH changes.23

Homeopathic artificial tears, such as Similasan, do not fall under the ophthalmic monograph and are not evaluated by the FDA for safety and effectiveness. Instead, they fall under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.24 Currently, homeopathic drug use is allowed in over-the-counter (OTC) artificial tears so long as the drugs are listed in the Homoeopathic Pharmacopoeia of the United States (HPUS). The FDA requires these homeopathic drugs meet standards of active ingredients regarding strength, quality and purity as specified in the HPUS.24,25

|

Keeping It Fresh

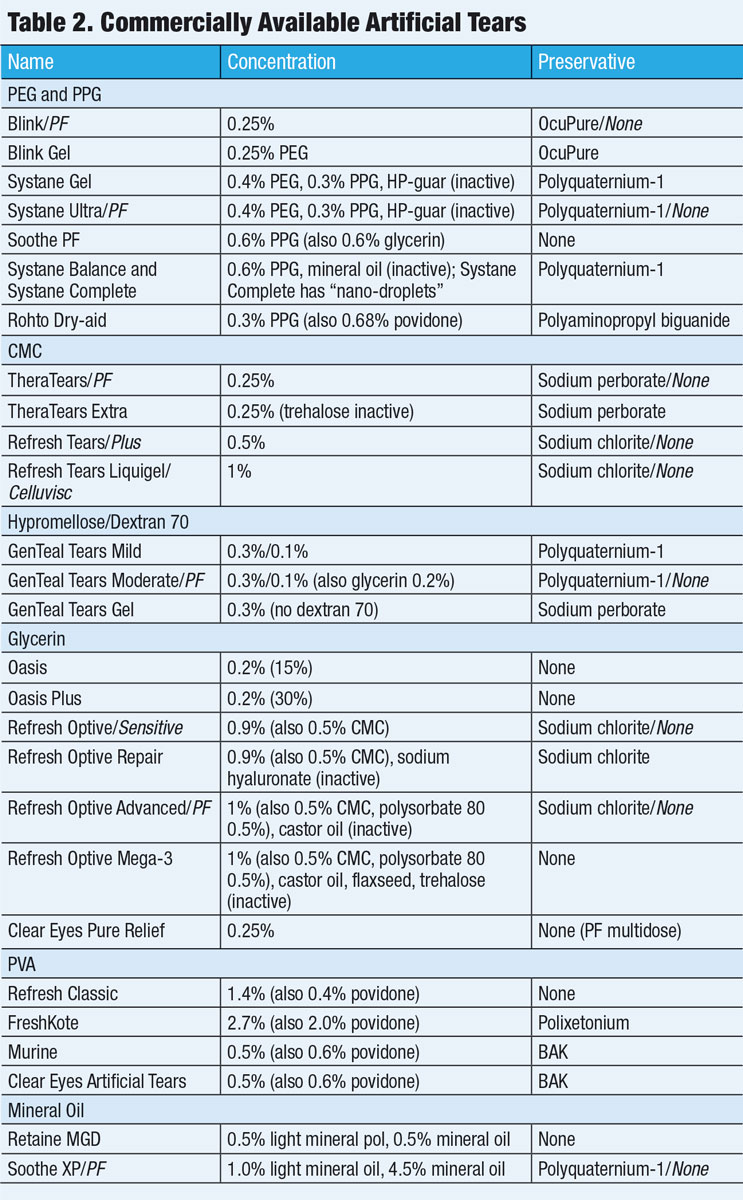

All multidose artificial tears must contain at least one substance to inhibit microbial growth and include appropriate guidelines for proper use (Table 2). In the United States, multidose eye care products undergo preservative testing that must pass the United States Pharmacopeia preservative effectiveness test.

The most commonly used preservative in ophthalmic drops is benzalkonium chloride (BAK), a quaternary ammonium compound that is an efficacious antimicrobial. It can range in concentration from 0.004% to 0.02% but is usually 0.01% in artificial tear formulations. BAK can cause both corneal and conjunctival cell apoptosis (in a dose-dependent manner, particularly in doses above 0.005%), delay wound healing, decrease goblet cell density and damage corneal nerves.26-29

While the most common artificial tears recommended by optometrists do not contain BAK, most OTC drops by major company and large store brands are preserved with 0.01% BAK. Even “softer” preservatives, such as sodium chlorite, can have potential negative effects on the ocular surface, although more studies are needed to compare them with non-preserved formulations.30

Most artificial tear brands now have unit-dose vials available in preservative-free formulations. In 2016, the FDA approved the first preservative-free multidose artificial tear, Clear Eyes Pure Relief (Prestige Brands). This drop uses a gas permeable unidirectional filter in the bottle tip to avoid contamination.

|

| Because many glaucoma drugs and generic artificial tears that contain BAK can cause punctate epitheliopathy, glaucoma patients should avoid using preserved artificial tears. |

Making the Right Choice

There is a dearth of randomized controlled trials that compare the efficacy of commercially available artificial tears. The FDA approval process for artificial tears does not require individual study submissions, and much of the available research is industry-funded—which can further complicate drawing clinically applicable evidence. A 2016 meta-analysis reviewed 43 head-to-head artificial tear trial studies and concluded that while patients treated with artificial tears experience better symptom relief than those treated with placebo tears or not treated at all, it is unclear whether some artificial tears are better than others at relieving patient symptoms.8

An optimal artificial tear provides efficacious, long-lasting relief from symptoms and has good instillation comfort and low blur. These can be imparted by the drop’s surface tension, pH, viscosity, duration of action and the presence or absence of preservatives. Other factors to consider include the ease of instillation and the cost:

- Drops of higher viscosity can provide a longer duration of effect but may also come with a higher incidence of visual blur.31 Lower viscosity drops tend to be better solutions for daytime use, and higher viscosity gel drops should be reserved for nighttime application.

- Cost can be the primary reason patients discontinue treatment.32 The cheapest artificial tears are generic brand PVA tears, which cost less than $2 per 15mL. Branded artificial tears can cost two to seven times more, with prices typically ranging from $8 to $13 for a 10mL to 15mL bottle. Generic formulations may be available for many branded artificial tears, but the inactive ingredients and preservatives will vary significantly. When recommending preservative-free drops, costs may increase significantly (particularly when dosing many times daily).

- Burning or stinging, which can occur when a patient’s tear pH does not align with the pH of the instilled drop, during instillation can significantly deter compliance with drop regimens, and a trial may be necessary to find the artificial tear that best matches a patient’s own tear pH.33 Discomfort can also be addressed by switching to a preservative-free drop.

- In-office education with artificial tears is integral. Studies show that the majority of patients, particularly elderly patients, who use chronic drop therapy have poor instillation technique.34,35 Unit-dose vials may present more challenges to these patients, but results are mixed.36,37

Artificial tear substitutes generally target at least one tear film layer, so understanding the primary deficiency of your patient’s tear film should help guide your treatment strategy. However, many patients have overlap in different areas of tear film deficiency, and those with a primary lacrimal insufficiency will represent a minority of your patient population. New formulations, such as Refresh Optive Advanced and Systane Complete, target multiple tear components to appeal to a broader range of patients.

A significant portion of patients using artificial tears may also wear contact lenses. Several artificial tears have been studied in contact lens wear, but most artificial tears are used off-label in contact lens patients without incidence.

Treatment Pearls

Keep in mind these practice tips when recommending artificial tears to DED patients:

- Most of your patients will likely have mild DED and should start with a low viscosity artificial tear. Modern lubricants outperform older lubricants, such as povidone and PVA, so clinicians should recommend more efficacious lubricants unless cost is a major concern.11 Generic preserved drops should only be considered for occasional use in mild DED patients with episodic symptoms due to the overwhelming presence of BAK in these drops.

- When an artificial tear is not well tolerated or is insufficient for relief, consider active ingredients and mechanisms of action when choosing an alternative. Move toward higher viscosity gel drops when symptoms are not well controlled after dosing every four to six hours.

- All patients with moderate to severe disease should ideally be on preservative-free formulations, as should any patient using artificial tears more than four times daily.

- Preservative-free drops should also be used for glaucoma patients on chronic-preserved glaucoma medications, postoperative patients who require lubrication and patients with acute keratoconjunctivitis.

- DED and significant MGD should be targeted with a lipid-based artificial tear. Using a drop that simply increases aqueous volume in patients with a deficient tear lipid layer may increase symptoms.38

Thanks in part to the FDA ophthalmic monograph for OTC ophthalmic drug products, a plethora of artificial tear options exists. As front-line eye care providers for dry eye patients, we must be equipped to offer our patients specific recommendations for drops, as no single drop works in all clinical scenarios. The art of medicine is applying our science to meet the needs of our diverse patient populations.

Drs. Horton, Reinhard and Horton are optometrists at the Cincinnati VA Medical Center and adjunct faculty members at the Ohio State University College of Optometry.

1. Farrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IO, Schaumberg DA. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:90-8. 2. Hikichi T, Yoshida A, Fukui Y, et al. Prevalence of dry eye in Japanese eye centers. Graef Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233(9):555-8. 3. Doughty MJ, Fonn D, Richter D, et al. A patient questionnaire approach to estimating the prevalence of dry eye symptoms in patient presenting to optometric practices across Canada. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74(8):624-31. 4. Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea. 2011;30(4):379-87. 5. Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocular Surface. 2017;15(3):575-628. 6. Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline. Care of the patient with ocular surface disorders. www.aoa.org/documents/optometrists/CPG-10.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018. 7. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. Dry eye syndrome. www.aao.org/ppp. Accessed June 15, 2018. 8. Pucker AD, Ng SM, Nichols JJ. Over the counter (OTC) artificial tear drops for dry eye syndrome. Cochrane. 2016;2. 9. Food and Drug Administration: Ophthalmic Drug Products for Over-the-counter Human use; Final Monograph. 21 CFR Parts 349 and 369. Federal Register 1988;53(43):7076-93. 10. Qian G, Simmons PA, Xu S, et al. Carboxymethylcellulose binds to human corneal epithelial cells and is a modulator of corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(4):1559-67. 11. Moshirfar M, Pierson K, Hanamaikai K, et al. Artificial tears potpourri: a literature review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1419-1433. 12. Korb DR, Scaffidi RC, Greiner JV, et al. The effect of two novel lubricant eye drops on tear film lipid layer thickness in subjects with dry eye symptoms. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82(7):594-601. 13. Scaffidi RC, Korb DR. Comparison of the efficacy of two lipid emulsion eyedrops in increasing tear film lipid layer thickness. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(1):38-44. 14. Simmons PA, Carlisle-Wilcox C, Chen R, et al. Efficacy, safety, and acceptability of a lipid-based artificial tear formulation: a randomized, controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Clinical Therapeutics. 2015;37(4):858-68. 15. Simmons P, Carlisle C, Shi G, Vehige J. Clinical comparison of lipid-based and aqueous lubricant eye drops. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(15):4329. 16.Code of Federal Regulations. Over-the-counter (OTC) human drugs which are generally recognized as safe and effective and not misbranded. 21CFRI.330.1. www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=5b9cfa96ac759f232cdf16c19ac5f9cb&mc=true&node=se21.5.330_11&rgn=div8. Accessed June 15, 2018. 17. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the definition and classification subcommittee of The International Dry Eye WorkShop. Ocular Surface. 2007;5(2):75-92. 18. Cömez AT, Tufan HA, Kocabıyık O, Gencer B. Effects of lubricating agents with different osmolalities on tear osmolarity and other tear function tests in patients with dry eye. Current Eye Research. 2013;38(11):1095-1103. 19. Tong L, Petznick A, Lee S, Tan J. Choice of artificial tear formulation for patients with dry eye: where do we start? Cornea. 2012;31(Suppl 1):S32-36. 20. Stahl U, Willcox M, Stapleton F. Role of hypo-osmotic saline drops in ocular comfort during contact lens wear. Cont Lens Ant Eye. 2010;33(2):68-75. 21. Hill-Bator A, Misiuk-Hojło M, Marycz K, Grzesiak J. Trehalose-based eye drops preserve viability and functionality of cultured human corneal epithelial cells during desiccation. Biomed Research International. 2014;2014:292139. 22. Allergan Expands Refresh Portfolio With New Refresh Repair Lubricant Eye Drops.Chicago: PR Newswire. 2018. www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/allergan-expands-refresh-portfolio-with-new-refresh-repair-lubricant-eye-drops-300677992.htm. Accessed September 5, 2018. 23. Christensen MT. Corneal staining reductions observed after treatment with Systane. Advances in Therapy. 2008;25(11):1191-9. 24. US Food and Drug Administration. Manual of Compliance Policy Guides. Sec. 400.400. Conditions Under Which Homeopathic Drugs May Be Marketed. www.fda.gov/ICECI/ComplianceManuals/CompliancePolicyGuidanceManual/ucm074360.htm. Accessed May 30, 2018. 25. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Products Labeled as Homeopathic. Guidance for FDA Staff and Industry. 2017. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM589373.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018. 26. Chung SH, Lee SK, Cristol SM, et. al. Impact of short-term exposure of commercial eyedrops preserved with benzalkonium chloride on precorneal mucin. Molecular Vision. 2006;12:415-21. 27. Lin Z, He H, Zhou T, et al. A mouse model of limbal stem cell deficiency induced by topical medication with the preservative benzalkonium chloride. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(9):6314-25. 28. Chen W, Zhang Z, Hu J, et al. Changes in rabbit corneal innervation induced by the topical application of benzalkonium chloride. Cornea. 2013;32(12):1599-1606. 29. Pinheiro R, Panfil C, Schrage N, Dutescu RM. The impact of glaucoma medications on corneal wound healing. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(1):122-7. 30. Schrage N, Frentz M, Spoeler F. The Ex Vivo Eye Irritation Test (EVEIT) in evaluation of artificial tears: Purite-preserved versus unpreserved eye drops. Graef Arch Clin Exper Ophthalmol. 2012;250(9):1333-40. 31. LaMotte JO, Ridder WH, Kuan T, et al. The effect of artificial tears with different CMC formulations on contrast sensitivity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(13):3151. 32. Taylor SA, Galbraith SM, Mills RP. Causes of non-compliance with drug regimens in glaucoma patients: a qualitative study. J Ocular Pharmacol Thera. 2002;18(5):401-9. 33. Asbell PA. Increasing importance of dry eye syndrome and the ideal artificial tear: consensus views from a roundtable discussion. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:11:2149-57. 34. Tatham AJ, Sarodia U, Gatrad F, Awan A. Eye drop instillation technique in patients with glaucoma. Eye. 2013;27(11):1293-8. 35. Gao X, Yang Q, Huang W, et al. Evaluating eye drop instillation technique and its determinants in glaucoma patients. J Ophthalmol. 2018;1376020. 36. Parkkari M, Latvala T, Ropo A. Handling test of eye drop dispenser—Comparison of unit-dose pipettes with conventional eye drop bottles. J Ocular Pharmacol Thera. 2010;26(3):273-6. 37. Dietlein TS, Jordan JF, Luke C, et al. Self-application of single-use eyedrop containers in an elderly population: comparisons with standard eyedrop bottle and with younger patients. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2008;86(8):856-9. 38. Calvao-Santos G, Borges C, Nunes S, et al. Efficacy of 3 difference artificial tears for the treatment of dry eye in frequent computer users and/or contact lens users. European J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(5):538-44. 39. Sullivan BD, Crews LA, Messmer EM, et al. Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: clinical implications. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:161-6. |