New recommendations and research have changed the management landscape for dry eye disease (DED), as have new products and devices to test for hallmarks such as tear film homeostasis, hyperosmolarity, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD)and ocular surface inflammation.

These recent additions have led to questions about the dry eye standard of care and what tests are necessary to properly diagnose these patients.

“We don’t have a single gold standard test or even a symptom questionnaire that can make a definitive diagnosis in isolation,” says Dan Fuller, OD, chief of Cornea and Contact Lens Service at Southern College of Optometry. “Setting cut-off values to categorize dry eye patients as normal, mild, moderate or severe has proven challenging.” Instead, doctors need to obtain a symptom questionnaire, run a battery of tests, sift through the results and then correlate the information with the risk factors in the history, he explains.

Still, experts say you can keep it simple when working up patients.

The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II (TFOS DEWS II) report “really aims at letting anyone know that they can diagnose dry eye,” says Kelly Nichols, OD, MPh, PhD, Dean of the University of Alabama School of Optometry. “You don’t have to have expensive equipment and call yourself an expert or specialist to identify dry eye in clinical care.”

Atlanta’s Josh Johnston, OD, echoes this sentiment. “If you just keep it simple, if you talk to your patients and listen to your patients, and also have your technicians or staff ask about symptoms of dry eye during the exam, and you do the minimal amount of testing which may include fluorescein or lissamine green staining, that is low-level stuff that can get you to a diagnosis.”

These experts’ advice comes down to four simple steps to an easy—and accurate—dry eye diagnosis.

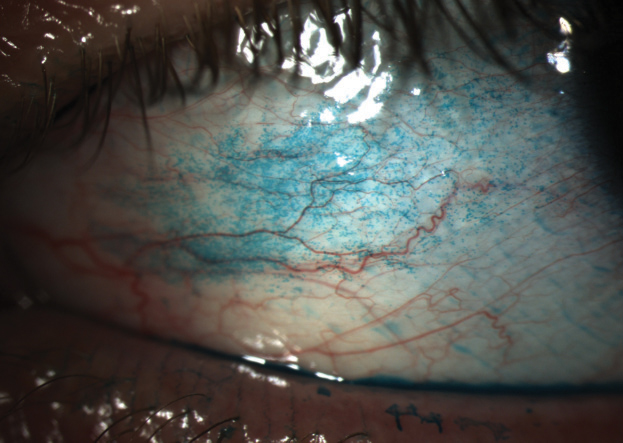

|

| Staining with lissamine green is an integral—and easy—step in the dry eye diagnostic process. Photo: Whitney Hauser, OD |

Step 1: History is Key

While big-ticket devices are helpful, a thorough patient history is a vital first step, experts say. A complete and accurate case history is arguably the most important part of a DED screening, says Whitney Hauser, OD, associate professor at Southern College of Optometry. “The practitioner should document the history of present illness and the review of systems that can shed light on the origin of the patient’s dry eye complaint and describe how the condition affects their quality of life.”

At Schaeffer Eye Center in Alabama, Jack Schaeffer, OD, asks patients four simple questions:

- Do you think your eyes look healthy?

- Do your eyes feel healthy?

- Are there times when your vision isn’t as clear as you’d want it to be?

- Do your eyes ever feel dry or uncomfortable?

Identifying prior and failed treatments is essential to avoid repeating inadequate options, Dr. Hauser adds. “The final opportunity in obtaining case history of the dry eye patient is to build rapport. Dry eye sufferers have higher levels of anxiety and depression than other patient populations and would benefit from developing a connection and trusting relationship with their doctor.”

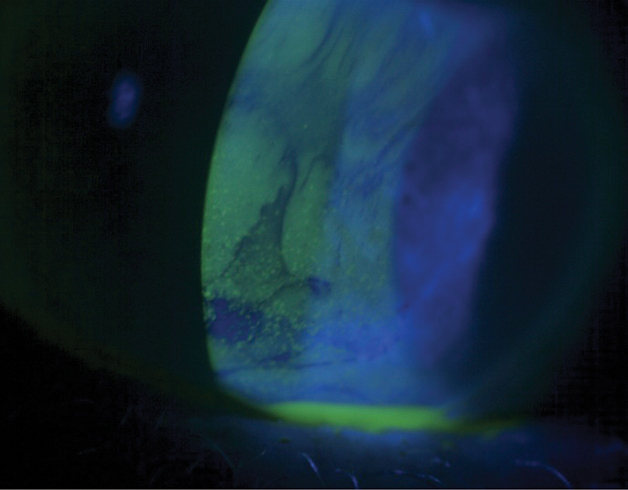

|

| Fluorescein staining remains a key part of any dry eye workup and doesn’t cost much money or time to perform. Photo: Whitney Hauser, OD |

Step 2: Questionnaire and Risk Factor Analysis

Next, a practitioner or staff member can go into a detailed history with a questionnaire such as the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) or a Standardized Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) to help you see if the patient is symptomatic or not, Dr. Schaeffer adds. “These will really determine if this patient should be medically triaged. Keep in mind, when you’re examining a patient, your staff should have a flow chart of what you do next when you have a symptomatic patient because you know there are issues identified by the screening questions. When you are dealing with an asymptomatic patient, when all the screening questions are negative, the direction is determined only after you examine the eye and there are signs of ocular surface disease.”

DEWS II recommends asking a short series of triaging questions to get an idea whether a patient has dry eye (see, “Triage Trouble-shooting from a DEWS II Insider,” p. 42). This can be done in tandem with a simultaneous risk factor profile, Dr. Nichols says. These questions—designed to uncover DED symptoms and rule out other diseases such as ocular allergy or Sjögren’s—can be asked during a case history or on an intake form. They cover topics such as previous artificial tear use, how a patient’s eyes feel, if they have dryness or discomfort, contact lens wear and medications.

While many different questionnaires are available, DEWS II recommends the OSDI or the Dry Eye Questionnaire 5 (DEQ-5).1

“Both short surveys give you a number as a result. And then you look at the score received from the survey in addition to some of the triage questions and risk factor analysis,” Dr. Nichols says.

The DEQ-5 offers brief questions about eye discomfort, dryness and watering, and addresses frequency of changes, fluctuation throughout the day and level of symptom intensity, Dr. Hauser explains. “The advantage of the DEQ-5 compared to the more widely recognized OSDI is ease of use, which makes it more applicable as a screening tool. Scoring the DEQ-5 requires simple addition with instructions provided at the bottom of the survey.”

|

| TBUT from simple dry eye, measured through fluorescein staining as seen here, is often confused with TBUT associated with epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, although it can be a combination of both. Photo: Jack Schaeffer, OD |

Step 3: Simple Tests

Following the questionnaire, Dr. Fuller suggests performing noninvasive testing prior to invasive testing, including tear prism height, debris in the tear film, lid margin contours, gland capping, abnormal blood vessel growth, notching or crusting that may indicate a Demodex infestation.

DEWS II recommends up to three noninvasive clinical tests for screening, Dr. Nichols says, which include tear film osmolarity, tear film break-up time (TBUT) and corneal staining assessment. A positive finding in any one of those three tests, in addition to abnormal results from the surveys, indicates DED, Dr. Nichols says. “Basically it’s the triaging questions + the risk factor assessment + abnormal findings on one of two surveys + one abnormal on one of three tests = dry eye.”

Fluorescein and lissamine green staining, in addition to meibomian gland expression and a lid seal test, don’t require much of an investment and will cover many issues pertaining to dry eye, Dr. Johnston adds.

Every practice can perform a conventional fluorescein TBUT. Noninvasive TBUT measurements can be performed with instruments such as corneal topographers and interferometers. Clinicians who do not have these technologies can do standard fluorescein TBUT tests.1 DEWS II recommends both corneal fluorescein and conjunctival staining, with a preference for lissamine green over rose bengal, as it is easier to obtain and less toxic.1 “There are a lot of new tests, but nothing is more important than fluorescein staining of the cornea, conjunctiva and lid margins,” says Dr. Schaeffer.

To determine if the dry eye is evaporative, DEWS II recommends expressing the meibomian glands to look at the quality and quantity of the secretions. “This will give you an idea if the lipid layer is disrupted, allowing excessive evaporation,” Dr. Nichols says. “Likewise for aqueous deficiency, you’d be looking at a low volume. The DEWS II recommendation is for the tear meniscus height to be measured. A lower meniscus would indicate a more severe version of aqueous deficiency.”

Step 4: Beyond the Basics

Other tools have come out in recent years to help with your DED diagnosis. Here’s a look at some new technologies currently on the market:

Tear osmolarity. “This can be measured by TearLab’s osmometer or the I-Pen tear osmolarity system (I-Med Pharma), the latter of which is newly emerging in the United States,” Dr. Hauser says. A hyperosmolar tear indicates a breakdown of homeostasis, causing tear instability and then inflammation and cellular apoptosis. “The breakdown further reduces the ability of mucins to lubricate,” Dr. Hauser says.

Adds Dr. Schaeffer: “Is everybody doing osmolarity testing today? At this point, no, but they should. You should have a base numeric level of dry eye, an objective score that you can observe after treatment. The change in osmolarity due to your treatment can help determine future strategy.”

Osmolarity has been a hot topic over the last few years, and many doctors worry about the extra cost, says Dr. Nichols. “Certainly, hyperosmolarity is included in the core mechanisms of dry eye. If you are measuring it, it is a good tool. Patients really like having a value to compare between visits. It makes them feel like they can do something about it, like high blood pressure.”

However, variability between the eyes is a hallmark of dry eye. In osmolarity testing, if a big difference in readings between the eyes exists, it could still indicate the patient has dry eye even if the numbers are normal, Dr. Nichols adds.

Meibography. This provides static or dynamic images evaluating the structure of the meibomian glands. Tortuosity, atrophy and ductal dilation may be observed and recorded, Dr. Hauser says. Traditionally, the glands can be observed by transillumination technique. However, this is difficult to record and details of the glands are limited, Dr. Hauser adds.

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) testing. “MMP-9 is a useful biomarker for detecting and managing dry eye disease,” Dr. Hauser says, and this point-of-care test, using InflammaDry (Quidel), identifies the presence of MMP-9 in tears (≥40ng/ml).

TearLab has applied for FDA approval of its universal MMP-9 platform test as well as osmolarity, although it’s not commercially available yet, Dr. Johnston says.

Aqueous volume testing. These include a Schirmer test or phenol red thread (PRT). Although both tests evaluate tear volume, testing parameters are different, Dr. Hauser says: normal values for Schirmer test are 10mm or greater, while PRT is 20mm or greater. Additionally, testing times are different: Schirmer is five minutes while PRT is 15 seconds, Dr. Hauser says.

Triage Trouble-shooting from a DEWS II InsiderTFOS DEWS II added another item to your dry eye diagnostic tool kit: triaging questions.1 The eight questions are designed to exclude other ocular surface conditions that can mimic dry eye. “The purpose of the triaging questions is really to aid in a simplistic diagnostic approach to help rule in dry eye or rule out other masking conditions,” says Dr. Nichols, a key contributor to DEWS II. She offers some insight on the objectives of the questions and how to best interpret your patients’ responses: 1. How severe is the eye discomfort? With the answer in hand, the doctor can then try to understand what might be creating the eye discomfort, she says. An appropriate follow-up question would be, “Is the discomfort in one eye or both?” If one eye is worse than the other, you’d try to sort through why that might be, Dr. Nichols says. 2. Do you have any mouth dryness or swollen glands? 3. How long have your symptoms lasted and was there any triggering event? 4. Is your vision affected and does it clear upon blinking? 5. Are the symptoms or any redness much worse in one eye than the other? 6. Do your eyes itch, appear swollen or crusty, or give off any discharge? 7. Do you wear contact lenses? 8. Have you been diagnosed with any health conditions (including respiratory infections) or are you taking any medications? After completing these questions, if you have identified another ocular surface condition, treat for that. If dry eye symptoms persist, consider going further with dry eye diagnosis and management, Dr. Nichols says. |

The Diagnostic Future

Looking ahead, biomarker research may one day play a key role in DED diagnosis, and ODs should get familiar with point-of-care tear analysis platforms as new additions using this concept are poised to come on the market, Dr. Nichols says.

“It’s important to note that, while we’ve learned a lot in dry eye, there are still things we don’t have a full understanding of, including how the eye’s ocular surface regulates itself in terms of homeostasis,” Dr. Nichols says. “We know there are hundreds of proteins and hundreds of lipids on the ocular surface and in the tear film, many of which are probably very important in terms of having them in the right quantity relative to other elements in the tear film. So as new diagnostic tests are created looking at specific proteins or lipids, we would hope to have paired treatments that would respond well. This is the whole idea behind biomarker research and then diagnostics around certain biomarkers.”

One final pearl for DED diagnosing from Dr. Schaeffer: screen early. “In early dry eye, patients are having visual fluctuation, and that could be the only observable sign. We need to pick that up during a refraction process. Also, dry eye is a progressive disease. By the time a patient is 50, you’ve probably lost the majority of time you have to really reverse any issues. All you are doing at that point is hopefully slowing down progression. Dry eye screening should start in a patient’s 20s and 30s.”

1. Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:544-79. |