Who is Your Patient?This series explores how both innate and acquired elements of identity manifest in the clinic:

|

The face of America is changing. By 2050, more than 50% of the population will be comprised of minority groups, which can cause unease for some who feel the changing demographics are also altering the character of the United States.1 But hopefully, this demographic inevitability will be an impetus for optometrists to better understand the needs, attitudes and interpersonal dynamics of individuals with backgrounds that differ from their own. Optometrists play an important role in these patients’ care. Epidemiological information tells us that visually handicapping conditions such as strabismus and amblyopia are prevalent in this population.1-5 Therefore, early and comprehensive vision care is vital.

While the need for comprehensive eye care is great in these patients, optometrists who feel comfortable evaluating them are rare. However, with a few easy and simple modifications to our schedules, examination techniques and communication styles, some of the apprehension can be eased. This article offers some clinical pearls and tips for those wanting to incorporate this much-needed service into their practices.

Hispanic growth is particularly astounding. This group alone contributed more than 50% of the US population growth in the last decade. The 2020 Census revealed that there are now 62 million Hispanic individuals in the US.2 By 2040, one of every four Americans will be Hispanic.*

|

|

Optometrists who can make Hispanic patients feel welcome will engender trust and loyalty among this growing population. Photo by Getty Images. Click image to enlarge. |

* In this article, the terms Hispanic and Latino are used as synonyms. Both are used here to refer to people of Latin American culture of any gender. Nowadays, the term Latinx is also used by a growing number of academics and indivudals.

Who are they? The Census defines Latinos as people descended from Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Central/South American or other Spanish cultures. Mexican Americans represent almost two-thirds of all Hispanics. This is not surprising since a great deal of the Southwest was once part of Mexico. Also, millions of Mexicans have worked in the United States for many decades, including the agricultural fields. Puerto Ricans, who are American citizens by birth, are one of every 11 US Hispanics; outside of the island, they usually live in enclaves in the Northeast and Central Florida. One of every 30 US Hispanics are Cuban, and most reside in Florida and the Northeast. Hispanics also include many other groups from Central America, South America and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean.

Hispanic people are descendants of three groups: European (mainly from Spain and Portugal), Indigenous and African. Latinos may have more or less of each component, depending on their country or region of origin. For example, I was born in Puerto Rico. I have 79% European, 12% Indigenous and 6% African ancestry. It is clear that it makes no sense to label Latinos into any traditional racial categories.

|

|

Click image to enlarge. |

Latinos are younger (median age close to 30 years) than the US population (median age nearly 39 years). This fact means that you are more likely to see younger families. It is an opportunity to be the optometrist of several generations of them.

These individuals tend to have larger households: 26% live in five-person families or more, about twice that of other groups. This implies that caring for one family member is more likely to be known and appreciated by other members of their families.

Latinos represent over 10% of the nation’s buying power ($1.7 trillion). In just nine years (2000 to 2009), Hispanic buying power increased 69%, compared to 48% for other groups. This implies that you have great opportunities to provide quality eye care services and eyewear to them.

|

|

Hispanic families can be large. Try to accommodate the inclusion of relatives in the clinic when feasible and desired by the patient; for example, to assist with translation. Click image to enlarge. |

What is Culturally Competent Care?

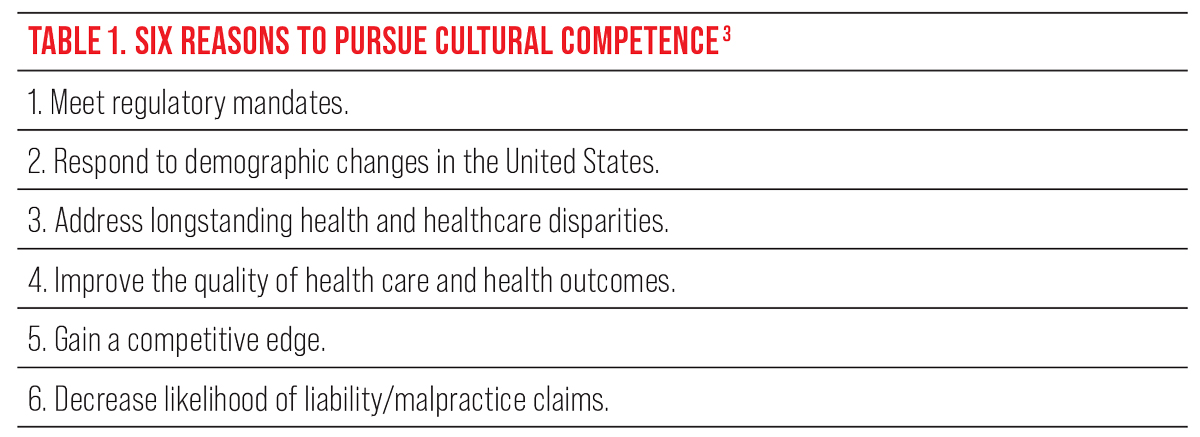

The notion of cultural competence implies developing the knowledge, skills and attitudes that allow us to understand, become aware and adapt our care to the patient’s needs and expectations. The purpose is to reduce healthcare disparities that arise from cultural barriers, improving outcomes and the patient’s sense of receiving empathic care.3 It has also been defined as “the ability of systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs, and behaviors, including tailoring delivery to meet patients’ social, cultural and linguistic needs.”4 The Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO) cites six critical reasons for ODs to develop skills in this area (Table 1). Some US states already require optometrists to fulfill an annual continuing education requirement in cultural competency, and others are likely to follow.

Becoming culturally competent implies cultural humility, which has been described as “a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture, but one starts with an examination of her/his own beliefs and cultural identities.”5 For instance, even aside from our family backgrounds and cultural identities, we optometrists all practice and espouse medical culture, a data-driven and pro-treatment mindset that can be at odds with patients who value their personal or spiritual beliefs at least as highly.

Of course, some skeptics brush all this off as another form of political correctness, arguing that it is the task of US citizens from other cultures to assimilate into mainstream American society. I feel that attitude creates blind spots in the way one approaches eye care, reduces our effectiveness and limits the growth of our practices.

Opinions and willingness to pursue cultural competency will differ, but adopting this approach takes less effort than you may realize. Some practitioners believe that becoming culturally competent is a complicated task. I often tell them that most of us already practice some form of cultural competence. For example, when we examine children, we adapt our language, gestures, equipment and examination to their needs. When we examine the elderly, we may modify the speed of our exam, lighting, contrast and tone of voice. It is no different when we examine patients of different ethnicities, values, ages, religions or national origins: we adapt our methods and demeanor to serve their needs better and achieve better outcomes.

Eyecare professionals who want to serve Hispanics and prosper as a result of their growth must become culturally competent. We all have cultural eyeglasses that filter our perceptions and judge other groups’ judgements. As Huff and Kline have expressed, to provide culturally competent care, one must “examine our own perceptions, stereotypes and prejudices toward the target group and be willing to suspend judgments (where they exist) in favor of learning who these people really are rather than who or what you might think they are.”6

Editor’s note: To augment Dr. Santiago’s commentary about Hispanic Americans, we have asked several optometrists who see other distinct population groups to share their experiences. Look for these contributions in a series of sidebars throughout this article. For an in-depth discussion of the Black experience in optometry, see the article by Dr. Essence Johnson.

The Asian Population: Diverse Unto ItselfBy Mary Hoang, OD, and Gary Chu, OD Dr. Hoang is an assistant professor at SCO. Dr. Chu is vice president of professional affairs at NECO. The Asian American group is a growing minority.1 However, the population is far from homogenous and more nuanced than statistics depict. Though they (or their ancestors) are from the same continent, most do not share the same language, beliefs, customs or history. Grouping this population into a single entity masks meaningful distinctions. Nevertheless, we will attempt to elucidate some beliefs based on the limited research available. Asians have immigrated to North America for myriad reasons. Some came for educational opportunities, while others immigrated because of occupational shortages. Some Asian groups may have entered the United States via refugee status. Hence, the history and socioeconomic status of each group is vastly different; their understanding of US culture and the English language also varies considerably. Some commonalities include respect for authority, value of education, providing for one’s family above all else and a stigma related to mental health issues. When caring for an Asian American patient, providers must have cultural considerations in mind, such as the patient’s belief regarding etiology of illnesses, unfamiliarity of Western medicine and methods, and language barriers.2-3 While diverse Asian ethnic groups share some commonalities regarding healthcare beliefs, it’s important to note that each group also has unique cultural beliefs about health and illness. These may also be further influenced by religious dogma. There are also situations to consider within the context of multigenerational households. For example, a patient is likely making their medical decisions collectively with their family members instead of by themselves. Understanding an Asian American patient’s health beliefs and perception of present illness is important to care for them effectively. For example, improper diet and stress as causation of illness and routine exercise as illness prevention are consistent beliefs across many Asian American subgroups. The Chinese perspective is influenced by traditional Chinese medicine, which is rooted in maintaining a balance between yin and yang. An imbalance in these forces, it is believed, may result in illness.4 A traditional Vietnamese belief is that there is a balance of hot or cold wind in one’s body, better known as “hơi”, and “giác” is a remedy to balance the elements in which heated glasses are placed onto the skin to draw out the bad wind. This treatment leaves a round, red mark that has led to Vietnamese parents being prosecuted for child abuse. Nowadays, this is better known by the mass media as “cupping” after it was popularized by athletes like Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps as a way to heal faster. Despite the popularity of alternative medicine such as cupping, healthcare providers have limited knowledge of traditional Asian interventions, which impacts outcomes for Asian Americans. Patients may not take their medicine for a variety of reasons. It is the provider’s responsibility to find out why. They may be using alternative traditional treatments. Spending time to understand these practices will aid the provider to negotiate the best ways to manage the patient’s ocular conditions.

Studies indicate both Western and non-Western patients prefer a partnership style of communication when discussing their health care, but a paternalistic communication style prevails among Asian American families. This is likely in part due to Southeastern Asians adhering to a social hierarchy, even in the context of their health care. Doctors are generally accepted to be higher on the social hierarchy and respect must be given to people of this high status; patients will defer to the doctor and their medical recommendations out of respect. Subsequently, a partnership communication style may not be the most appropriate in the cultural context of many Asian American patients. If mutual medical decision making is desired, doctors must overcome the patient’s default to deference and politeness and encourage them to become more active participants in their health care.5 It is especially challenging to provide care for a patient who does not speak your language, and initially, our Asian American patients may appear to be agreeable to the prescribed treatment plan if some communication is lost in translation. Many will use their children to interpret, but that adds other challenges, since the child is not equipped to handle diagnoses that are vision- and life-threatening. To overcome this, it is recommended to use certified medical interpreters who understand the cultural context and can act as a liaison for both cultures. Offering interpretation relieves anxiety because the patient’s concerns and complaints will be addressed and engenders a trusting relationship between doctor and patient. It is also important to remember that there will be various subcultures within an Asian American family. Keep in mind the culture of the family’s origin, the culture of the immigrant family moving to North America and the culture of their children—who may feel they do not belong to their culture of origin or the culture of North America. Noting these struggles and providing compassion to these challenges will aid the provider in navigating how one may approach the delivery of care. For example, a parent may not want their child to wear soft contact lenses because of cost but their child may want contact lenses to fit in at school. Each Asian American group faces vastly different challenges, and their understanding of US culture and English varies widely. Caring for a patient who speaks a different primary language requires thought and skill, and a cooperative approach will appeal to the preferred partnership style of communication and keep family members involved. Even though many Asian American groups hold some common beliefs regarding health care, each subgroup holds its own cultural views about health and illness. Understanding these perspectives will help the provider effectively to manage the patient’s ocular conditions.

|

Beware of Generalization, Stereotyping and Chauvinism

There are barriers to the goal of becoming culturally competent. As we approach our patients, we form hypotheses about them.

Consider: Mrs. Maria Rodriguez from Brownsville, TX, with a Spanish accent, comes to my office. I wonder if she is Mexican American, a devout Catholic with a large extended family. This statement is a hypothesis or generalization that I am willing to test during my conversation with her. I am open to other alternatives and willing to suspend my judgment until I find out. On the other hand, if based on the same facts, I conclude that she is Mexican American, devout Catholic with a large extended family, and I am not willing to test this hypothesis, I am stereotyping her—a barrier in the road to becoming culturally competent.

Chauvinism—the belief that one’s group, nation or culture is superior to others—is often a barrier to accepting others. Each of us may feel that “our” way of life seems normal and right, while others may appear abnormal, irrational or inferior. Chauvinism may show in our interactions with our patients. For example, we may ignore their explanation of their illnesses. We may belittle or even prohibit the use of traditional remedies. This behavior is a sure way to lose the confidence of your Hispanic patient.

Optometry Inside the Arctic CircleBy Gregory Black, OD, Ft. Lauderdale, FL Assistant professor at Nova Southeastern University

On Alaska’s northwestern coastline near the Bering Strait, 33 miles north of the Arctic Circle, lies the village of Kotzebue. There, Maniilaq Eye Clinic is the sole provider for an area the size of the state of Indiana. Dr. Meagan Lincoln, who was born and raised in Kotzebue, established the current optometry and opticianry programs within the hospital in 2016, and I have been involved in village travel since 2017. There are 11 villages within the Maniilaq service area, with Kotzebue as the regional hub. Among the population, 83% of the 8,623 residents are Inupiat. As with every population, there are subtle and not-so-subtle differences. With a population density of 0.20 per square mile, it is understandable that patients will have a larger personal space bubble than elsewhere in the US. In this isolated area, patients are more independent in most aspects of life. In the optometry clinic, for instance, they prefer to insert and remove their contact lenses themselves. Discussion of the impact of birth control pills and hormone replacement therapy for dry eye and LASIK considerations is a more delicate conversation in Kotzebue than it is in South Florida. Accustomed to a good deal of personal space, patients need to be warned that they will be tilted back for BIO prior to the procedure rather than while I tilt them back, otherwise they will flinch. These were learned very quickly due to the reactions experienced, and my approached changed. The use of nonverbal communication is more common in this region; for example, kids will use an upward eyebrow movement to signal yes and scrunch their nose to signal no. I no longer ask a yes/no question if a child is behind the phoropter or I have my back to them. A couple of characteristics of the population have made refraction and drop instillation significantly easier. Patients actually know which is better one or two and will even volunteer “same” without prompting. The vast majority of pediatric patients accept drops if it is explained that it will only sting for 30 to 45 seconds. The pediatric patients have a bravery that I have not seen in other populations. In speaking with nurse practitioners and dental colleagues, they report a similar response to injections and dental procedures. As a provider who has cared for many different cultures, races and religions in both South Florida and now rural Alaska, I have learned that by displaying respect, concern and compassion for your patients, you will be seen as a trusted provider. You will make mistakes, but learn from them. Look for clues of discomfort, which are usually going to be nonverbal. Listen when a patient gives you advice. Also remember that everyone is an individual; just because something is common in a population doesn’t mean that it applies to everyone. If at all possible, seek out advice from an optometrist representative of the population you are serving. Dr. Lincoln is extremely helpful in that regard for me. Caring for Indigenous populations may not be an everyday experience for many optometrists; when it arises, knowing some basic characteristics of the group will help you build a rapport one-on-one. |

Hispanic Cultural Values

The patient’s habits and beliefs are often the best guides to culturally competent care. Each cultural value will guide our behavior toward each group. Here we must walk a fine line: it is essential to treat each person as an individual and not assume that their membership in a particular group necessarily means they will behave in a certain way. However, I would like to articulate several traditional core values of Hispanics that may be present in your patient:

Respeto. This means the consideration and deference each person deserves as a human being, but also as a function of their age, education, reputation and achievements.

Implications: As an eye care professional with a high level of education, optometrists receive respeto from their patients. By the same token, the patients expect respeto from their doctors. One of the most common faux-pas of non-Hispanic optometrists is to greet the patient with their first name on their first encounter (“Good morning, Pedro”) as a way to seem friendly and put them at ease. You should instead refer to the patient with their surname (“Welcome, Mr. Rodriguez” or “Señor Rodriguez”). It may be acceptable to use their first name as you get to know them over time.

The patient may be using complementary medicine (such as herbs) and even consulting a folk healer (curandero). It’s essential to push back against your own bias toward medical culture and instead respect the patient’s cultural traditions while still counseling them on what you consider the best course of care, without expressing disdain or ridicule.

Some older Hispanic patients may avoid direct eye contact. You may misinterpret this behavior as a lack of interest in your conversation. Avoidance of eye contact from the patient is a sign of respect to you as a doctor and an authority figure. Accept that and maintain your eye contact with the patient.

Familismo. This cultural value implies that the family is the pillar of society, and there is a strong sense of worth associated with belonging to a family. The family typically includes the father, mother, siblings, grandparents, nieces, nephews and godparents.

Implications: Hispanics may come with family members to the appointment. Consider a larger waiting room if you practice in a neighborhood where many Hispanics visit your office. Be willing to allow a family member inside the exam room if the patient desires.

Family members usually assist others when they need help with their care. For example, they may help dispense eye drop medications to an elderly relative as required. They may be the ones to remind their family members of their medical appointments. Therefore, it is practical and helpful if that family member accompanies the patient to the exam room.

Also, be aware that many decisions about eye care and eyewear are made with the counseling and assistance of other family members. Although the patient has the ultimate voice, you and your staff should allow the family member’s involvement in the decision process.

Personalismo. This value relates to the importance of developing sincere, authentic and caring relationships among human beings above other priorities.

Implications: Get to know your Hispanic patient’s interests, hobbies and close family members. Before initiating your examination, devote time to chat about personal matters.

Sit closer (less than one meter), lean forward and provide handshakes as needed. This behavior will help you obtain confianza—your patient’s trust—to envisage you as someone who cares about them. Gaining confianza will allow you to be not only the optometrist for the patient but more likely the optometrist that other family members will choose and prefer.

Things to Consider During Muslim Patient EncountersBy Mawada Osman OD, MS, Columbus, OH Assistant professor of clinical practice and outreach coordinator at OSU College of Optometry The Islamic faith encompasses a largely diverse group of people from many different ethnicities, cultures and backgrounds. In the United States, the majority of Muslims are immigrants from Middle Eastern/North African and South Asian countries, which make up about 30+ nations. Although the diverse cultural and ethnic background is intertwined with an individual’s religious beliefs, there are certain aspects that are unique to the Islamic religion that may have an impact on health behaviors and overall healthcare experiences and outcomes. In Islam, both men and women are required to behave and dress modestly. This includes wearing loose-fitting clothing for both genders and wearing a head covering known as a “hijab” for women. As modest behavior is highly recommended in Islam, you may find some patients reluctant to shake hands with a provider of the opposite gender. This should not be taken personally or interpreted as offensive. Instead, you could greet your patient with a head nod and raising your hand to your chest as a way of showing respect and understanding. Patients may also prefer and request to have a provider of the same gender. When possible, these services should be provided to the patient. However, if not possible, especially with smaller clinics, it is important to request permission from the patient whenever performing clinical examination/procedures that require direct touch of the patient—for example, lifting the eyelids. Wearing medical gloves would also be preferred. One aspect that we do not think much about as optometrists is a patient’s dietary requirements. Pork consumption is prohibited in Islam. We need to keep this in mind when prescribing oral medications such as antibiotics that come in capsule form. The capsules are made of pig-based gelatin and some patients might feel uncomfortable consuming such medications. Another medication we tend to prescribe as optometrists are AREDS2 supplements. Most come in softgel form, which also contains gelatin. Alternatives should be used when possible. Family plays an integral role in the Muslim community. Family members, both nuclear and extended, are consulted regarding important medical decisions, especially surgical procedures. Communicating and building trust with family members should be as much of a priority as it is with the patient—especially those family members that come in with the patient.

Creating a welcoming environment in your office space allows your patients to feel more comfortable and included. This can be done by displaying images of a diverse group of people on your office walls and website. You can take the extra step and reflect that interest by hiring a diverse group of individuals to be a part of your office team. A very important aspect in delivering culturally competent care to your Muslim patients is just getting to know them. Muslims are multi-ethnic and make up the second largest religion in the world. Have a conversation with your patient expressing your interest in learning more. The main holidays celebrated by Muslims are Eid Al-Fitr, which is celebrated after the holy month of Ramadan (a time of fasting and spiritual connection), and Eid Al-Adha, which is celebrated on the 10th to the 13th of the twelfth Islamic month (lunar calendar). Extending a simple “Happy Eid” greeting to your patient (or if you want to try the Islamic/Arabic greeting, you can also say “Eid Mubarak,” which translates to “blessed Eid”) reflects your appreciation for their culture and belief system. At the end of the day, the goal of cultural competence is to create a connection between you and your patient that allows for open communication, building of trust and ultimately providing excellent care. For a more detailed guide on the delivery of culturally competent care for Muslim patients, see “A Health Care Provider’s Guide To Islamic Religious Practices” by the Council on American-Islamic Relations. |

The Concept of Time

Many Americans display the characteristics of what can be described as a linear-active culture—they perform tasks one at a time, sequentially, and punctuality is considered very important. On the other hand, many Latinos display the characteristics of a multi-active culture. They may perform different tasks almost simultaneously. Human relations and transactions are considered more important than following a schedule.

You may find that some of your Latino patients may not show on time and you may be irritated by this, possibly coloring your impression of this individual. To avoid such an outcome, prepare yourself for at least the possibility of this. You may want to ask them to arrive earlier than expected to make sure you keep your schedule, or you may decide to have some flexible appointments where they are examined in the order they come to your office.

The Concept of Space

The Latino distance of comfort for interaction is about 80cm (roughly 2.5 ft.)—closer than the typical American. Hugging, handshakes and kissing on the cheek among Hispanic women are acceptable.

As you examine your patient, learn to sit closer to them and express friendship through handshakes. Distancing yourself is a sure way to be perceived as a cold, unfriendly doctor.

Caring for Orthodox Jewish CommunitiesBy Daniella Rutner, OD Associate clinical professor and chief of vision rehabilitation at SUNY College of Optometry Judaism is an ethno-religion (i.e., conferred both through birth and through conversion) comprised of the beliefs and practices of the Jewish people as recorded in their several-millennia-old scriptures (chiefly, the Torah) and oral traditions (compiled in the Talmud). Since roughly the mid 19th century, it has consisted of three major denominations: Reform, Conservative and Orthodox. The latter, Orthodox Judaism—which counts itself historically the oldest of the three traditions—is strictest in practice, most recognizable in dress and, by intention, the least integrated into mainstream American culture. Notable examples of strict practice are dietary restriction (“keeping kosher”) and refraining one day per week from work-related activities (Sabbath observance every Saturday). Perhaps the most universally notable example of recognizable dress is the male head covering.

The “Orthodox” umbrella is quite wide, including within it “Ultra-Orthodox” subgroups such as Hasidic, Chabad and Yeshiva. A clinician treating patients from these Ultra-Orthodox subpopulations should be sensitive to some potential sources of cultural friction: Language. The more stringent Orthodox denominations (Hasidic and Yeshivish) are inclined to live and work in communities that proactively foster cultural insularity, and that reality may present the clinicians with some language barriers. Often, English is not the primary language spoken at home so much as Yiddish or Hebrew. Frequently, women moving within these subpopulations are more fluent in spoken and written English than their husbands or male relatives. Education. Adult educational levels vary greatly among the Orthodox Jewish population, spanning anywhere from advanced degrees to the equivalent of middle grade-school. It should be noted that in the more stringent yeshivas (schools), the English alphabet is not introduced until age 6 or 7. Physical modesty: touch. Typically, Orthodox Jews will avoid any form of touch with members of the opposite gender outside immediate family, often preferring to avoid even shaking hands. Accordingly, the physical examiner should minimize touch and attempt to educate the patient prior to touching. Gloves are advised, as they naturally work to emphasize the clinical nature of the interaction. Physical modesty: dress. Modesty is also reflected in Orthodox Jewish attire, extending even to the types of frames the young male patient might be permitted to adorn himself with in school or within his social milieu. General propriety: speech. Many Orthodox Jews actively work to ethically monitor their own conversation, purging from their habits of speech aggressive commentary such as sarcasm and even, in some cases, needless discussion of trivialities. As a result, they may well be more sensitized to certain forms of “casual” or quasi-intimate conversation, with discussions that tread on private or personal matters very possibly making them uncomfortable. General propriety: physicality. A male and female ought not to be alone in a room with a closed door. If there are no cameras in the clinician’s room or window panels on the door, leaving the door slightly ajar will assist the patient’s general sense of propriety, as will having another person in the room (with the patient’s permission). Finally, it is important to note that eye contact is understood to belong to the realm of potentially intimate interactions and is best minimized by members of the opposite gender. The same is true of physical space; the clinician should try to avoid standing invasively close to the Orthodox Jewish patient. |

The Language Barrier

One of the biggest obstacles to optimal care is the language barrier, especially for older Hispanics. The ideal solution is learning basic conversational Spanish by the optometrist. The second best is hiring caring bilingual staff members who may serve as interpreters.

If you do this, make sure they are trained and understand the rules of interpretation. They must not add or omit any words nor hold side conversations with the patient. The first-person approach is recommended—if the patient says, “I have pain in my right eye,” the interpreter should say and interpret it as “I have pain in my right eye.” The doctor must always look and address the patient during the interview, not the interpreter. Possibly the best positioning is the interpreter sitting beside and slightly behind the patient, facing the doctor. Alternatively, you may use telephone or video interpreting services.

You should also provide printed information in the native language of the patient. You may acquire educational materials in Spanish printed by the American Optometric Association. You may use or refer the patient to websites and YouTube videos with information on eye diseases; just make sure that the information is accurate and up to date.

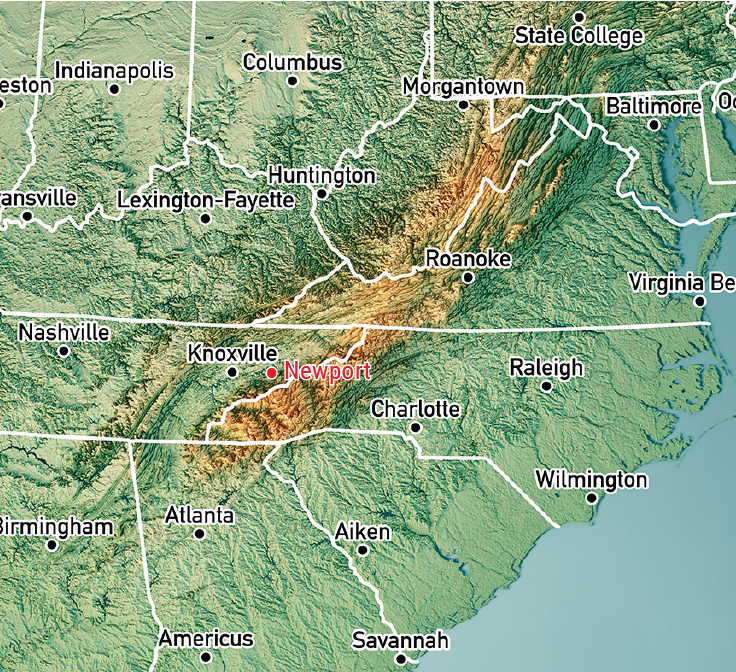

Optometry in Appalachia: Challenge Your AssumptionsBy Kurt Steele, OD, Newport, TN Private practitioner at Vision Source of Newport

The people of Appalachia have been unfairly stereotyped by Hollywood as uneducated and backwards in just about every way. Having practiced in Newport, TN (population: 6,868) for the last 26 years, I’ve seen this unfair bias against rural America disproven time and time again. Yes, a significant percentage of this community typically does not pursue higher education. In the 2020 census, only 12% of Newport residents reported having a college degree. But this affects their earning potential more than anything else. The median household income of $24,124 is well below the national average of $67,521 and the poverty rate here is 42.9% (vs. 11.4% nationally). However, this tight-knit, hardworking community takes care of one another and is part of the reason we also have an extremely low cost of living. While 90% of the population may be white, I don’t see this manifest as a bias against other races, although I’m sure that many of my patients would feel like a fish out of water in Los Angeles or New York. It is interesting to note that two of our last three city mayors have been African American. This is a devoutly Christian community, and in fact, one of the things I enjoy doing with my patients after giving bad news is praying. Most of our patients love that. I always pray with them when I am referring them for cataract surgery and especially for a sight-threatening issue. Sometimes we even pray just if they are having some bad times in life. That might be something different we do here that may not be done in other areas of the country. This strong religious conviction does not, however, mean my patients are opposed to heeding medical advice—another stereotype out there. As a matter of fact, as someone who’s been a member of a small rural community for so many years, I feel the trust our patients have in us is unmatched in any other geographical area. These are people I go to church with, see at the grocery store and encounter in all walks of life. They know me, they respect me and they listen to me. Financially, there are definite hardships to address without sacrificing quality of care. We often have to work with our cataract surgeon and/or retina surgeon to allow flexible payments when a patient requires tertiary care. We have to get creative on charging. For anyone without insurance, we charge a flat fee per year that covers not only that emergency visit but all follow-ups and a full exam with a pair of single vision glasses. Also, being in a small town, we can often barter with patients for our services. For the first corneal foreign body I removed, I was reimbursed four jars of moonshine! In terms of eye disease prevalence, we see lots of diabetic retinopathy, as people in rural Appalachia certainly have dietary staples that are not the best. Also, we have lots of welders and see a fair amount of foreign body cases from local medical providers. We are also in an area that sees more retinitis pigmentosa than most ODs would. I think it’s safe to say most optometrists in the US don’t have much experience with rural life. It’s definitely different than what we see happening in the rest of the country. I certainly have no complaint of an “overabundance” of optometrists, and we serve on staff at our local hospital. We get all referrals from local medical facilities, and it makes for a very interesting and varied career. I love my community and cannot imagine practicing anywhere else. |

Health Care Needs

Hispanics have the second-highest prevalence of adult obesity (45%) and hypertension (44%) after Black individuals.8,9 They also have the second-highest prevalence of diabetes (17%) after Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders.10 However, for some Latinos, chubbiness is seen as a sign of healthiness. You should be comfortable counseling them with sensitivity and respect about weight, blood glucose control and healthier lifestyles.

About one-third of Hispanic individuals with diabetes have diabetic retinopathy.11 This high prevalence implies that all Hispanics must have a comprehensive dilated fundus examination at every visit.

About one-fourth of Latinos lack a primary health care provider.11 You may maintain a list of primary physicians that you deem are more likely to be Latino-friendly to refer your patient as needed. One of every five Latinos may lack health insurance.12 However, many are willing to pay out-of-pocket if they value their doctor and eye care services.

Caveats and Takeaways

In this article, we have expressed generalizations about Hispanics and other groups. Avoid stereotyping your patients. Be aware that some of these generalizations may not apply to your patient. Be open-minded and be willing to learn about the patient you have in front of you.

Latino presence is here to stay. Their numbers are growing fast, and within 20 years, the group will fully constitute one-quarter of American society. Their buying power is also increasing at a rapid pace. The demand for eye care services will dramatically increase during the coming decades. Understanding Latino cultural values and becoming culturally competent can serve them better and promote the growth of our practices.

Dr. Santiago, a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry (AAO), is a diplomate in the AAO’s Public Health and Environmental Section. He is also vice president of VOSH International, chair of the Public Health Committee of the Latin American Association of Optometry and Optics, and a professor and director of research at the Inter American University of Puerto Rico (IAUPR) School of Optometry. Previously, he was he was dean of IAUPR School of Optometry, founding dean of Midwestern University Arizona College of Optometry and president of the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO). He was also a member of ASCO’s Cultural Competence Guidelines Committee. Dr. Santiago has no financial interests to disclosure.

|

1. Colby, SL, Ortman, JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. US Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau (2015). Available at www.census.gov/content/dam/census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. 2. 2020 census results. US Census Bureau US Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau (2021). Available at www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2020/2020-census-main.html. 3. ASCO Guidelines for culturally competent eye and vision care. Diversity task force, Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry. Released June 2008. Available at www.optometriceducation.org/files/guidelines_culturallycompetenteyeandvisioncare.pdf. 4. Betancourt, J., Green, A., Carrillo, E. (2002). Cultural competence in health care: Emerging frameworks and practical approaches. The Commonwealth Fund. Available at www.commonwealthfund.org. 5. Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care for the Poor and Underserved.1998;9(2):117-125. 6. Huff RM, Kline MV. Health Promotion in Multicultural Populations: A Handbook for Practitioners and Students, 3rd edition. Sage Publications (2007). 7. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-18. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 360 (2020). 8. Ostchega Y, Fryar CD, Nwanko T, Nguyen DD. Hypertension prevalence among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2017-2018. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 364 (2020). 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021): Hispanic/Latino Americans and Type 2 Diabetes. Available at www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/hispanic-diabetes.html. Accessed Jan 4, 2022. 10. Mora N, Kempen JH, Sobrin L, Lucia. Diabetic retinopathy in Hispanics: a perspective on 11. Disease Burden. Amer J Ophthalm. 2018(196):xviii–xxiv. 11. Livingston G, Minushkin S, Cohn D. Hispanics and Health Care in the United States. In Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project (2008). Available at www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2008/08/13/hispanics-and-health-care-in-the-united-states-access-information-and-knowledge. 12. Office of Health Policy. Health insurance coverage and access to care among Latinos: recent trends and challenges (2021). Issue Brief #HP-2021. Department of Healtn anmd Human Services. Available at: aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/68c78e2fb15209dd191cf9b0b1380fb8/aspe_latino_health_coverage_ib.pdf. |