|

A 37-year-old Hispanic male presented to the emergency department with complaints of blurred vision in his left eye for six months. He reported that his vision had drastically worsened over the preceding week. He denied any active pain or inflammation in his eye, though he did note an episode of photophobia and redness that had occurred in the weeks leading up to his rapid vision decline.

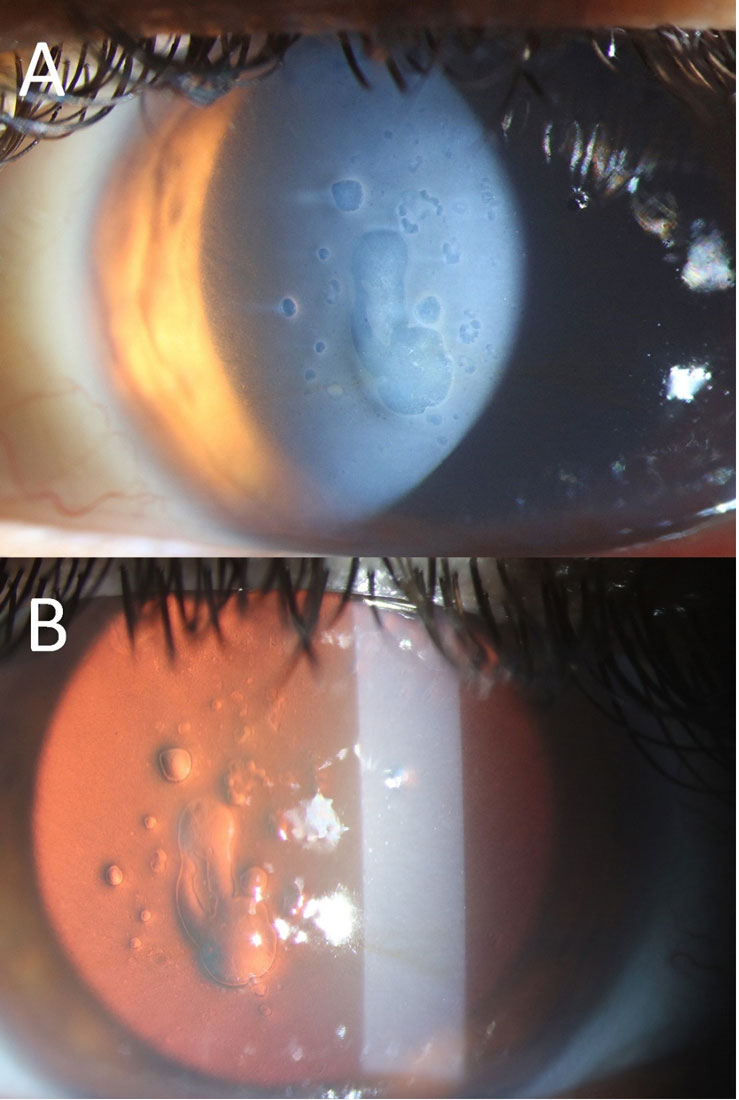

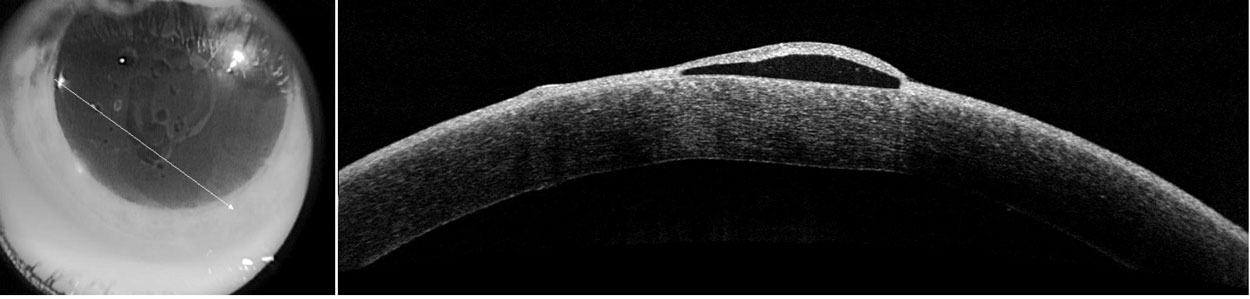

The patient’s entering visual acuities were 20/20 in the right eye and counting fingers at three feet in the left. His intraocular pressures were 17mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS, and there was no afferent pupillary defect. The slit lamp and fundus examinations of the right eye were unremarkable. The conjunctiva of the left eye was white and quiet without foreign body presence. The cornea was diffusely hazy with subtle stromal thickening throughout the central region. There were numerous large epithelial bullae but no infiltrate or keratic precipitates (KPs) (Figure 1). The anterior chamber was deep and formed, and there were no appreciable cells or hypopyon. The dilated fundus examination of the left eye was grossly normal. Additional imaging was completed with anterior segment OCT (Figure 2).

A thorough review of the patient’s personal and family ophthalmic history was taken. The patient denied any contact lens wear, prior ophthalmic surgery or ocular trauma. He was not taking any oral or topical ophthalmic medications, but he did endorse a history of perioral cold sores. He denied knowledge of any family history of ocular disorders or surgery.

|

Fig. 1. Slit lamp examination on direct (A) and retro (B) illumination reveals large, scattered epithelial bullae with mild corneal haze. Note the quiet conjunctiva (A). Click image to enlarge. |

In cases such as this one, it is helpful to review common causes of corneal edema. First, consider the possibility of a degenerative disorder of the cornea. Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy is the most common endothelial disorder. These patients are typically older and experience a gradual decline in their vision bilaterally.1 The condition causes accelerated loss of endothelial cells over a patient’s lifespan, at a rate which may lead to pathologic characteristics. Clinical exam reveals the presence of endothelial guttae, stromal thickening and epithelial bullae in advanced cases. As mentioned before, our patient did not have any history of such disorders.

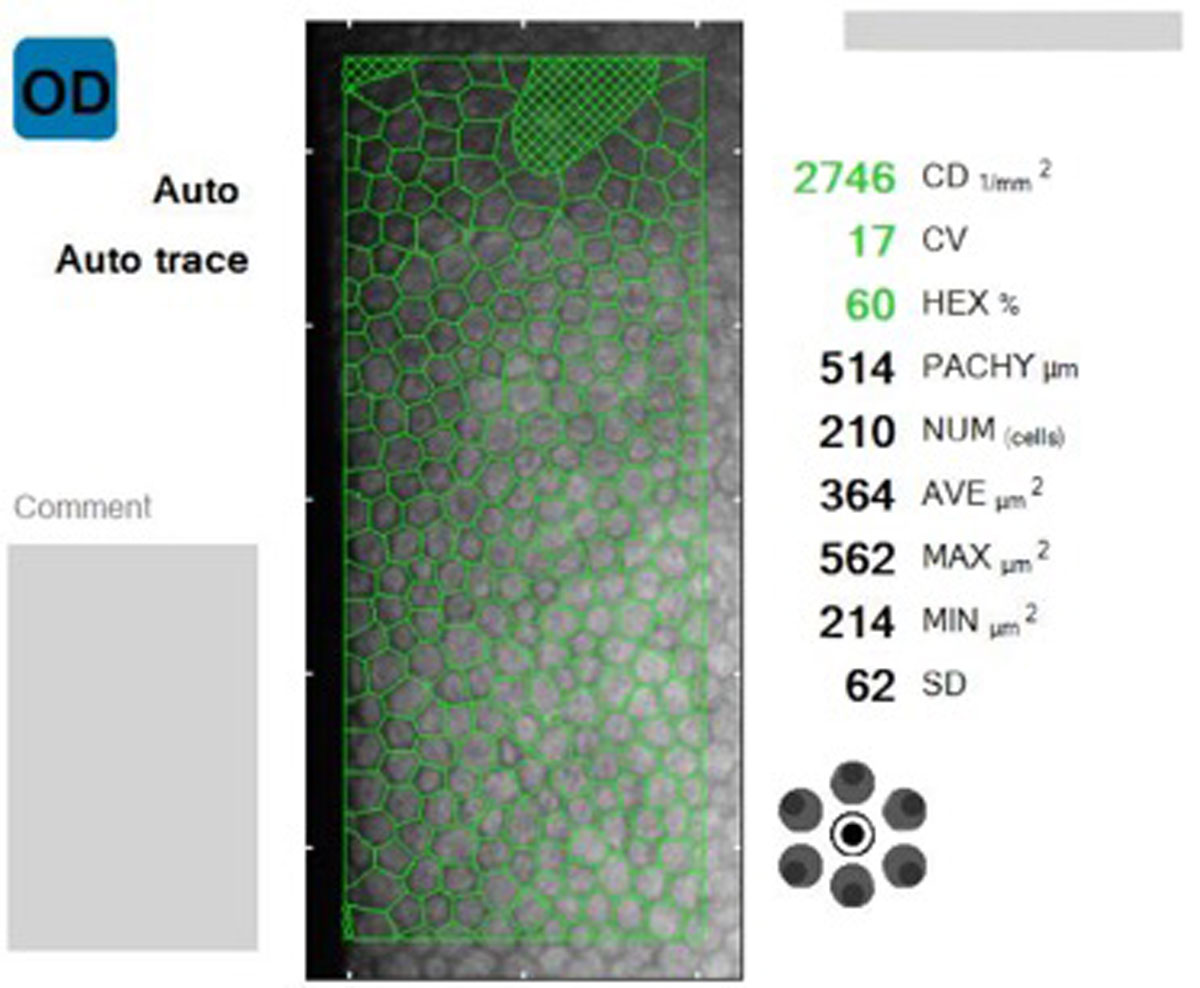

Specular microscopy was completed to evaluate the endothelial health of the asymptomatic eye (Figure 3). The cell count was within normal limits for his age, and the cells were mostly hexagonal as one would expect in a healthy eye. The central cornea was slightly thin at 514µm, eliminating the possibility of subclinical edema. Other endothelial disorders that can cause corneal edema include posterior polymorphous dystrophy (PPMD), congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) and iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome. In our patient, there were no clinical signs of any abnormalities of the contralateral eye, ruling out PPMD and CHED. ICE syndrome typically presents as a unilateral condition, but it is associated with iris atrophy and elevated intraocular pressure, two features not seen in our patient.

Corneal edema can also present secondary to ocular trauma and surgery. Pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (PBK) occurs after cataract surgery and leads to irreversible corneal swelling due to loss of endothelial cells during surgery. Though the overall chances of developing this condition are low, factors that lead to an increased risk of PBK include pre-existing endothelial compromise, increased phacoemulsification energy, combined anterior vitrectomy, direct endothelial damage from surgical instruments and anterior chamber intraocular lens placement.2

Ocular trauma can cause refractory corneal edema, particularly when there is direct damage to the endothelium or a rupture in Descemet’s membrane. It is also common to see temporary corneal swelling in cases of corneal abrasions, but this typically resolves as soon as the epithelial defect closes. Our patient denied any ocular surgery or trauma, ruling out these etiologies.

Corneal edema can also result from infectious keratitis. Associated clinical findings include the presence of an infiltrate, epithelial defect, redness, photophobia and anterior chamber inflammation. In our patient, there was no infiltrate, defect or inflammation present, ruling out microbial keratitis.

Viral infections such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) can also cause corneal edema. Herpetic keratitis is most clearly recognized when epithelial involvement (e.g., a dendrite) is present. The absence of dendrites, however, does not exclude a viral infection. HSV may manifest as stromal keratitis or endotheliitis. Stromal HSV often presents with corneal edema, haze and deep corneal neovascularization. Herpetic endotheliitis typically presents with a red, photophobic eye that has keratic precipitates underlying the area of stromal edema. In many cases, the KPs may be difficult to visualize initially due to corneal clouding.3

|

Fig. 2. Anterior segment OCT through the cornea reveals prominent epithelial bullae and minimal stromal thickening. There were no endothelial KPs visible on any OCT images. Click image to enlarge. |

So, What's the Deal?

Our patient’s clinical presentation was unique in that he had significant epithelial bullae but in an otherwise white and quiet eye. He reported an episode of redness and photophobia that preceded his visit to the emergency department, but those symptoms had resolved by the time he sought care. Given the patient’s age, unilaterality and prior history of cold sores, a suspected diagnosis of herpes simplex endotheliitis was made. The patient was started on valacyclovir 500mg three times daily, sodium chloride drops four to six times daily and preservative-free artificial tears four times daily.

At a five-day follow-up, his vision had improved to 20/150. At that time, prednisolone acetate was added four times daily. One month after his initial presentation, the patient’s corneal edema had completely resolved, and his vision was 20/30 without correction. He was tapered off the topical corticosteroids, and the valacyclovir was discontinued. Despite lacking classic findings of herpetic keratitis, the exam and course of improvement supported a herpetic component.

Similar cases have been reported, including a 62-year-old female who presented with unilateral corneal edema and epithelial bullae but lacked anterior chamber inflammation, KPs or elevated intraocular pressure. Topical steroids alone did not improve the clinical findings. The patient therefore underwent an aqueous tap confirming HSV and went on to receive successful treatment with topical corticosteroids and oral antivirals.4

Another case involved a 60-year-old male with unilateral corneal edema and bullae in an otherwise quiet eye. There were no KPs or anterior chamber cells, but intraocular pressure was elevated in the affected eye at the initial visit. At follow-up, he was noted to have developed epithelial dendrites, and corneal cultures were positive for HSV.5

A third case of corneal bullae from viral endotheliitis in a quiet eye revealed cytomegalovirus as the causative agent, further illustrating that not all disease processes present with classic findings.6

|

| Fig. 3. Specular microscopy was performed in the patient’s fellow eye, revealing healthy endothelial cells without corneal edema. Endothelial cell analysis was attempted OS, but data was unable to be collected. Click image to enlarge. |

Take-home Message

This column highlights the diverse clinical manifestations possible with herpes simplex keratitis. When faced with a divergent clinical picture, it is helpful to think logically through the differential diagnoses. Many etiologies can be ruled out, leaving the practitioner with a narrow list of suspects to work through.

In this case specifically, the patient was treated empirically given the known history of HSV and the larger clinical picture. He continues to be monitored for recurrence but was doing well at the most recent follow-up.

Dr. Bozung works in the Ophthalmic Emergency Department of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (BPEI) in Miami and serves as the clinical site director of the Optometric Student Externship Program as well as the associate director of the Optometric Residency Program at BPEI. She has no financial interests to disclose.

|

1. Moshirfar M, Somani AN, Vaidyanathan U, Patel BC. Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. 2. Feizi S, Corneal endothelial cell dysfunction: etiologies and management. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2018;10:2515841418815802. 3. Mannis MJ, Holland EJ. Cornea. Edinburgh, NY: Elsevier; 2017. 4. Papaioannou L, Tsolkas G, Theodossiadis P, Papathanassiou M. An atypical case of herpes simplex virus endotheliitis presented as bullous keratopathy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(6):475-7. 5. Athmanathan S, Sridhar MS, Anand R, et al. Herpes simplex virus bullous keratitis misdiagnosed as a case of pseudophakic bullous keratopathy with secondary glaucoma: an unusual presentation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2001;1:2. 6. Chiang CC, Lin TH, Tien PT, Tsai YY. Atypical presentation of cytomegalovirus endotheliitis: a case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19(1):69-71. |