Who is Your Patient?This series explores how both innate and acquired elements of identity manifest in the clinic:

|

Let’s be reminded of the oath we took when becoming a doctor of optometry. When we recited the optometric oath, we affirmed that the health of our patients will be our first consideration; we will provide professional care for the diverse populations that seek our services with concern, compassion and due regard for their human rights and dignity; we will work to expand access to quality care and improve health equity for all communities; we will place the treatment of those who seek our care above personal gain and strive to see that none shall lack for proper care; and we will do the utmost to serve our communities, our country and humankind as a citizen as well as a doctor of optometry.1

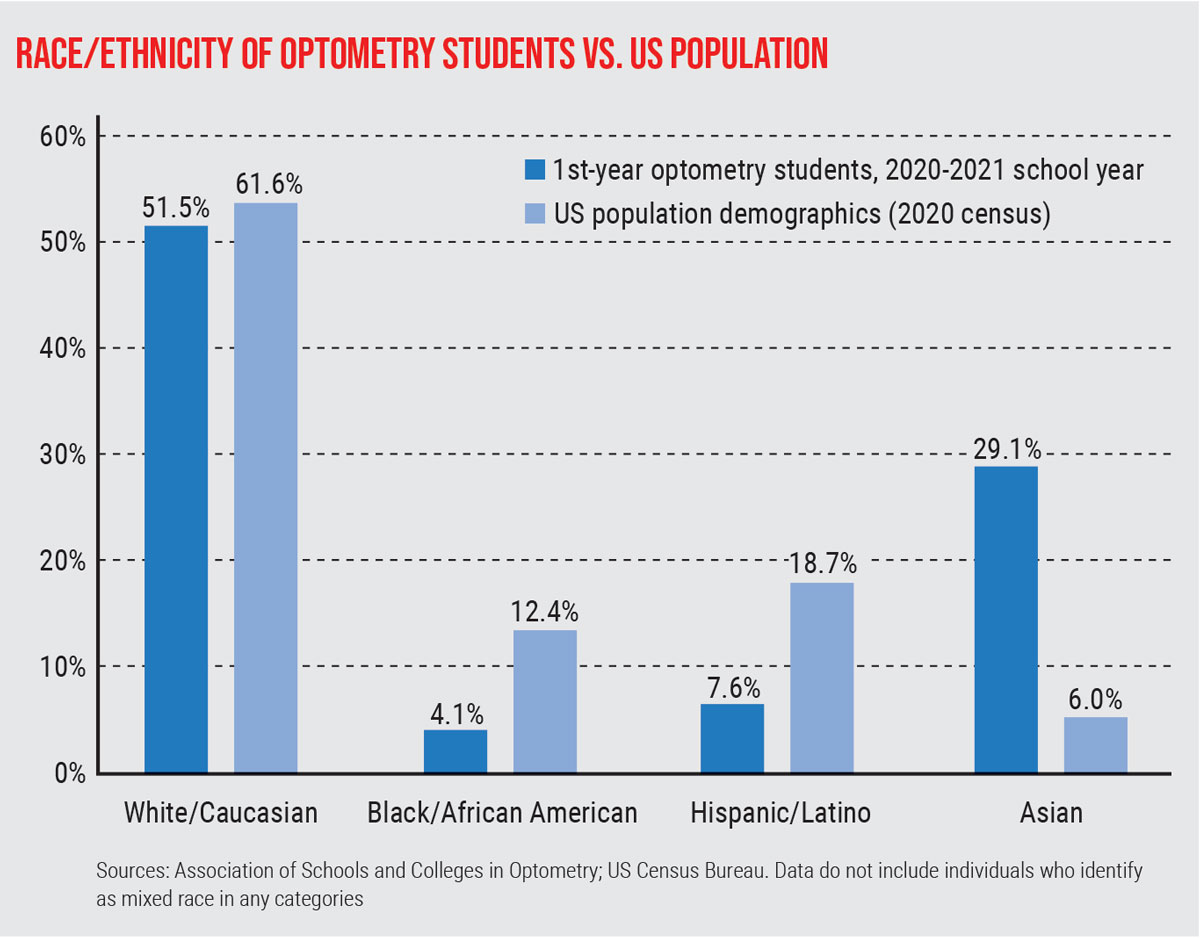

When you take a minute to reflect on certain aspects of the optometric oath, it is a mighty task that nearly 46,000 optometrists have committed to assume the care of the eyes of over 331 million individuals in the United States. The population of Blacks or African Americans alone or in combination with other racial groups totals 46.9 million people.2 Providing eye care to this demographic is a formidable task for all providers. Relegating the care of the entire Black community to the 1.8% of optometrists that look like them proves to be an even more daunting task.3

Studies show minority physicians are more likely to practice in underserved areas and have patient populations with higher percentages of minorities than their white colleagues.4 There are also studies that show better health outcomes for Black patients when they are in the care of a Black doctor. Although about a quarter of Black adults would prefer to receive care from a Black doctor, 65% found it difficult to find a doctor that shared the same experiences and background as them, but 75% of Black adults found it easier to find a doctor that treated them with dignity and respect.5

|

Nwamaka Ngoddy, OD, practices in Atlanta and is also the creator of Anwuli Eyewear, a line of frames specifically to fit the facial features of the Black and African American community. Click image to enlarge. |

While it is a preference for some to have a Black doctor, the reality is, finding a Black doctor can be like searching for a needle in a haystack. While a history of racism, discrimination and mistreatment has created a communal mistrust, disengagement and sometimes avoidance of the healthcare system altogether in the Black community, there is more myth than truth that Black people generally harbor negative attitudes and beliefs regarding their health, specifically when it comes to eye care.

Society has created the narrative and many providers have adopted the perception that Black patients do not care about their health and do not prioritize their eye care. Comments collected from 17 focus groups of 119 older African Americans residing in Birmingham and Montgomery, AL “were predominantly positive (69%), highlighting the importance of eye care and behavior in their lives and attitudes that facilitated care.”6 Affordability and accessibility to care are more commonly reported than generalized apathy as reasons to why many Black patients have not had an eye exam.

Biases—conscious and unconscious—prove to be barriers to care for our minority patients, especially those of the Black community. It is most often assumed that when a patient is lost to follow-up, they have given up on their care instead of considering whether they had a positive experience, had a life-changing event, lost insurance coverage or just simply forgot. Doctors from all backgrounds can better connect with Black patients by establishing trust, effective communication (time and tone), patient education (teach) and assisting their patients with ways to make it easier to access care (transportation).

|

Adam Ramsey, OD, co-founder of Black EyeCare Perspective (BEP), treats a patient at his practice in West Palm Beach, FL. Click image to enlarge. |

Increase Accessibility

Expanding office hours (evening and/or weekend options), providing a list of alternative transportation options and patient appreciation gifts in the form of gift cards for gas or rideshare services are a few ways to help patients get to the office. Another way to improve accessibility is by bringing your services into the Black community. Schools, churches, nursing homes, mobile clinics and volunteer opportunities connect the Black community with optometrists to receive eye care, eyewear and education.

If you are personally unable to increase accessibility for patients due to local socioeconomic factors (i.e., low income, lack of insurance, difficulty making appointments due to work schedule or lack of childcare), being able to refer patients to other offices or clinics, or direct them to programs for assistance helps them keep their health a top priority while also feeling like they are the doctor’s top priority. Breaking down barriers to care can be achieved by getting to the patient.

|

This graph shows the disproportionate ratio of Black/African American individuals pursuing a career in optometry relative to the population as a whole. Click image to enlarge. |

It Begins With Trust

The infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study was not about eye care, but the trauma it imparted on the relationship the Black community has with health care overall has transcended specialties and families, passing on an understanding of distrust from generation to generation. What many would prefer to write off as an old wives’ tale is a part of history and sadly remixed in other examples that resonate even currently in the Black community. Whether it be Henrietta Lacks, Serena Williams, their own mother/sister/friend or themselves, many members of the Black community can unfortunately raise their hand admitting they have been victimized by yet another system they thought was in place to help them.

Studies that have looked at the racial differences in patient trust have correlated it with the effectiveness of the communication behaviors of the physician. Trust in minority patients, particularly in the Black community, has been associated with patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, continuity of care and improved health.7 Therefore, breaking down barriers to care simply starts with building trust.

|

From left to right: Jacobi Cleaver, OD, director of program management, BEP; Emely Miniño Soto; Tiffany Humes, OD; Essence Johnson, OD, chief visionary officer, BEP; Avia Dolberry and Ijem Ozodigwe. Phographed at the 2021 American Academy of Optometry meeting. Click image to enlarge. |

Be Aware of Behavior

An observational cross-sectional study on the impact of perceived discrimination in health care on patient-provider communication defined perceived discrimination “as the perception of differential and negative treatment because of one’s membership in a particular group.”8 Similar to the association of the lack of trust to lower patient satisfaction and poorer health outcomes, a patient’s perception of discrimination in healthcare settings can cause a cascade of negative mental and physical health outcomes.

The study also highlighted that discrimination in the form of racism and classism was perceived most often amongst African Americans, whereas white patients felt like their provider did not listen to them. Consciously or unconsciously, when a patient does not feel heard by their doctor, not only do they feel disrespected, but their trust, satisfaction and motivation to stay engaged in their healthcare diminishes.

When doctors communicate with patients, it is important to be aware of both informational and affective behaviors. Informational behaviors, such as data collecting, had a lesser effect on trust in Black patients when compared to affective or partnership building behaviors. Doctors are not dictators giving commands, but the doctor-patient relationship is an ever-evolving partnership where together they collaborate coming up with treatment plans and learning from one another. Creating a positive rapport helps remove barriers to care especially in the Black community, although it takes time to establish. Physicians can monitor their affective behavior by knowing these aspects of rapport building:7

• positive (compliments, laughter)

• emotional (empathetic or concern statements)

• negative (criticism, disagreements).

• social (small talk)

• understanding (paraphrasing or repetition)

Remember, it is not only what you say but how you say it or do not say it. Verbal as well as nonverbal communication can equally convey a tone. Even with a mask on, people can tell if you are speaking to them with a smile and it takes self-awareness and practice to not mirror a patient’s negative affect. Similar to how imagery is used to help combat jitters before speaking in front of a crowd, picture your patient as a member of your own family and ask yourself if that was your parent/grandparent/sibling, how would you like them to be treated?

Be mindful of pronouns and whether or not a patient prefers to be addressed by their first and/or last name. If you are unsure how to pronounce someone’s name, simply ask them to say it for you so you don’t mispronounce it. Breaking down barriers to care can be achieved by talking to patients with a positive tone.

|

From left to right: Breanne McGhee, OD, trustee at-large, National Optometric Association (NOA); Essence Johnson, OD, region IV trustee, NOA; Sherrol Reynolds, Immediate Past NOA President and Edward Larry Jones, OD, current NOA President. Click image to enlarge. |

Take Time With Each Patient

With patients scheduled 10, 20 or even 30 minutes, the goal is to see each one as effectively and equitably as possible. Be mindful of how it may look from a patient’s perspective: How long are they in the office? How many patients are they witnessing being seen before them? Not every patient can understand the complexity of each individual’s case. Creating a standardized approach to every patient will create a cadence and routine patients will become familiar with over time, and they will grow to understand the elements of an exam and base their visits on quality over quantity.

An element of the exam that is often short-changed is patient education. Economic factors aside, the average health literacy in the Black community is perceived to be low. Quite frankly, in general people “don’t know what they don’t know.” They may not know their family’s health history due to complex family dynamics or a familial hierarchy. At least once in an optometrist’s career they will meet a patient with a “stigma” or “cadillacs.” This is another opportunity to break a barrier and bridge a gap through educating the Black community on astigmatism and cataracts, as well as the top diseases that cause blindness in racial and ethnic minorities—the “three silent killers:” diabetes, hypertension and glaucoma. Breaking down barriers to care can be achieved by spending more time with patients and making patient education a priority.

|

Darryl Glover, OD, co-founder of BEP. Click image to enlarge. |

Are We There Yet?

It is not uncommon in the Black community to take on a “do as I say” and not “as I do” mentality. Surveys show that four out of five Black people acknowledge eye exams should occur every year, but year after year less than half of the people in the Black community get their eyes examined.9 The same plan employed to get more Black people to the polls or to get the COVID-19 vaccine should also be employed for eye care with the same level of excitement and societal and political support. When asked, affordability and accessibility rank high on barriers to receiving eye care. On a national level, inadequate transportation options continue to have a negative impact on the health and well-being, particularly of the elderly in the Black community.6

|

Darryl Glover, OD, and future optometrist Emely Miniño Soto. Click image to enlarge. |

While research currently supports patients of the Black community that may be treated by non-minority doctors are at higher risk of adverse medical outcomes, it was the recommendations from American educator Abraham Flexner’s 1910 report that has negatively impacted Black doctors, and patients and the ramifications are still felt centuries later. Flexner’s findings resulted in the closing of all but two of the seven historically black medical schools that educated Black doctors at the time—Meharry Medical College and Howard University—and infected society with the belief that Black doctors should only treat Black patients, but if not properly trained and treated, the Black community would be a health threat to affluent white communities.

Preceding the release of the Flexner report, what is now known as the National Medical Association (NMA) was founded in 1895 by a group of physicians who were denied membership into other professional organizations and societies, like the American Medical Association which was founded in 1847.10 The American Optometric Association was founded in 1898; for some of the same reasons the NMA was established, 25 African American optometrists gathered with the purpose to establish a nationally recognized optometric association comprised of Black doctors. That meeting took place in the spring of 1969 and was the first of many for the National Optometric Association (NOA).11

With the mission of “Advancing the Visual Health of Minority Populations,” membership into NOA is open to all ODs with diverse backgrounds willing to make an investment in the future of optometry and eye health, and passionate about supporting NOA’s purpose to recruit minority students into the schools and colleges of optometry and placement into appropriate practice settings upon graduation, in addition to educating and caring for the community to eliminate barriers and disparities in eye health.

To become a member of NOA and help advance its mission, please visit nationaloptometricassociation.com.

Black EyeCare Perspective

It is in part from the network created by the NOA and its student organization (the National Optometric Student Association) and various summer programs (Texas Optometry Careers Opportunity Program at the University of Houston College of Optometry and the Pennsylvania College of Optometry’s Summer Enrichment Program), that optometrists Adam Ramsey, Darryl Glover, Jacobi Cleaver and myself were brought together. Collectively, we are working to redefine the color of the eyecare industry 1% at time through an organization called the Black EyeCare Perspective (BEP).

BEP was designed and created to cultivate and foster lifelong relationships between African American eye care professionals and the eyecare industry. BEP believes one must be united in their efforts and intentional in their impact to truly see the percentage of Black optometrists increase and reflect that of the Census-reported population (1.8% vs. 13%).

In 2020, BEP launched its 13% Promise initiative to encourage commitment and action among individuals and corporations to increase Black and African American representation in eyecare to align with the US Census for better health outcomes of underrepresented communities. Industry partnerships and targeted programming help support the vision of the 13% Promise: to create a pipeline for Black students into optometry, connect communities with Black eye care professionals and Black eye care businesses and cultivate relationships between Black optometrists and opportunities in the eye care industry.

BEP is also creating brave spaces and facilitating courageous conversations within the eyecare community through diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and influencing the mindset of the next generation of eyecare professionals to raise awareness and impact the industry in ways we have yet to see.

Black EyeCare Perspective Pre-Optometry Club

The Black EyeCare Perspective Pre-Optometry Club (BEPPOC), established in 2020, is the first pre-optometry club nationally recognized by the Associations of the Schools and Colleges of Optometry to ensure not a single potential Black or African American student or optometrist is ignored, discouraged or disadvantaged. Nearing a membership of 100 Black future optometrists representing 54 undergraduate institutions—15 being Historically Black Colleges and Universities—membership is free and meetings are held on the 13th of every month. BEPPOC is an integral part of the pipeline for increasing the number Black students entering the eyecare profession.

Minding Our "T"s

Black Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, white Americans—we all are all a part of this nation and the term American should ring synonymously with people from all backgrounds, not exclusively with just one group and independent of any other identifying or classifying factors. The health of our patients who are from diverse populations is our first priority. We all should continue to work to expand access to quality care and improve health equity for all communities and strive to see that no one lacks proper care.

The secret to creating a stronger connection between ODs and the Black community? Stop creating and accepting as inevitable a self-fulfilling prophecy that there are disparities in healthcare that disproportionately affect minority communities but there is nothing that can be done now to start breaking down the barriers that should’ve never been placed centuries ago.

By minding our “T”s—trust, time, tone, teaching and transportation—we can break down a few of those barriers to care for patients in the Black community. Together, we can do the small things that make a great impact not just in connecting with the Black community, but in enriching healthcare, advancing eye care and strengthening every doctor-patient relationship.

Dr. Johnson received her doctorate of optometry from the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University and is a community and correctional health optometrist who practices at Southeast Dallas COPC. She is also the chief visionary officer of Black EyeCare Perspective, co-advisor and co-founder of the Black EyeCare Perspective Pre-Optometry Club and the National Optometric Association Region IV Trustee. She is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision Care and is a member of the Transitions Optical diversity advisory board.

| 1. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org/about-the-aoa/ethics-and-values. Accessed December 27, 2021. 2. United States Census Bureau. www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html. 2021. Accessed December 27, 2021. 3. Black EyeCare Perspective. www.blackeyecareperspective.com/the-13-promise. Accessed December 27, 2021. 4. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, et al. The Right Thing to Do, The Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions. Institute of Medicine. National Academies Press. 2001. 5. Washington, J. New poll shows Black Americans put far less trust in doctors and hospitals than white people. www.theundefeated.com/features/new-poll-shows-black-americans-put-far-less-trust-in-doctors-and-hospitals-than-white-people. 2021. Accessed December 27, 2021. 6. Owsley C, McGwin G, Scilley K, et al. Perceived barriers to care and attitude about vision and eye care: focus groups with older African Americans and eye care providers. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006;47:2797-802. 7. Martin KD, Roter DL, Beach MC, et al. Physician communication behaviors and trust among Black and white patients with hypertension. Med Care. 2013;51(2):151-7. 8. Hausmann LRM, Hannon MJ, Kresevic DM, et al. Impact of perceived discrimination in health care on patient-provider communication. Med Care. 2011;49(7):626-33. 9. African-Americans need to make vision care a priority. www.ophthalmologymanagement.com/issues/2008/november-2008/stat-tracker. Ophthalmology Management. 2008. Accessed December 27, 2021. 10. Mitchell EP. The National Medical Association 1895-2020: struggle for healthcare equity in the United States of America. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(4):331-2. 11. National Optometric Association. www.nationaloptometricassociation.com/about-us/our-history. Accessed December 27, 2021. |