In 2017, the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) II Report updated the definition of dry eye disease, describing it as ‘‘a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface.”1 Recently, treatment has focused on meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), since it is the most common cause of evaporative dry eye.2 However, one must not lose sight of the multifactorial nature of dry eye, which requires treatment of each aspect of the disease, including blepharitis. Addressing eyelash and lid margin hygiene is an often overlooked component of a comprehensive treatment strategy.

Eyelashes protect the eye by preventing debris and particulate matter from reaching the ocular surface. Inferiorly, there are usually three or four rows with about 75 to 80 lashes, while superiorly five to six rows may be present with approximately 90 to 160 lashes.3 Each lash has a visible shaft above the skin surface and a follicle that lies below the lid margin. Lashes usually grow to 12mm in length and have a slight curvature.3 For proper function, the lashes must be durable, flexible and able to regenerate, as they fall out and regrow about every four to 10 weeks.3 For optimal health, both the lashes and lid margins need to remain clean and healthy.

Let’s examine the different forms of blepharitis, its treatment and care and how to manage this condition.

Etiology and Prevalence

Blepharitis, defined as an inflammation of the eyelid margin, can be either acute or chronic in nature. Acute anterior blepharitis can be caused by a variety of bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites; it is treated with topical or systemic medications.4,5 While acute infections tend to be irritating and can produce significant inflammation or even ulcerative lesions, once adequately treated they do not tend to contribute to chronic dry eye. However, if left untreated, the acute issues can become more entrenched, leading to lid margin alterations or loss of lashes that can have longer-term effects.

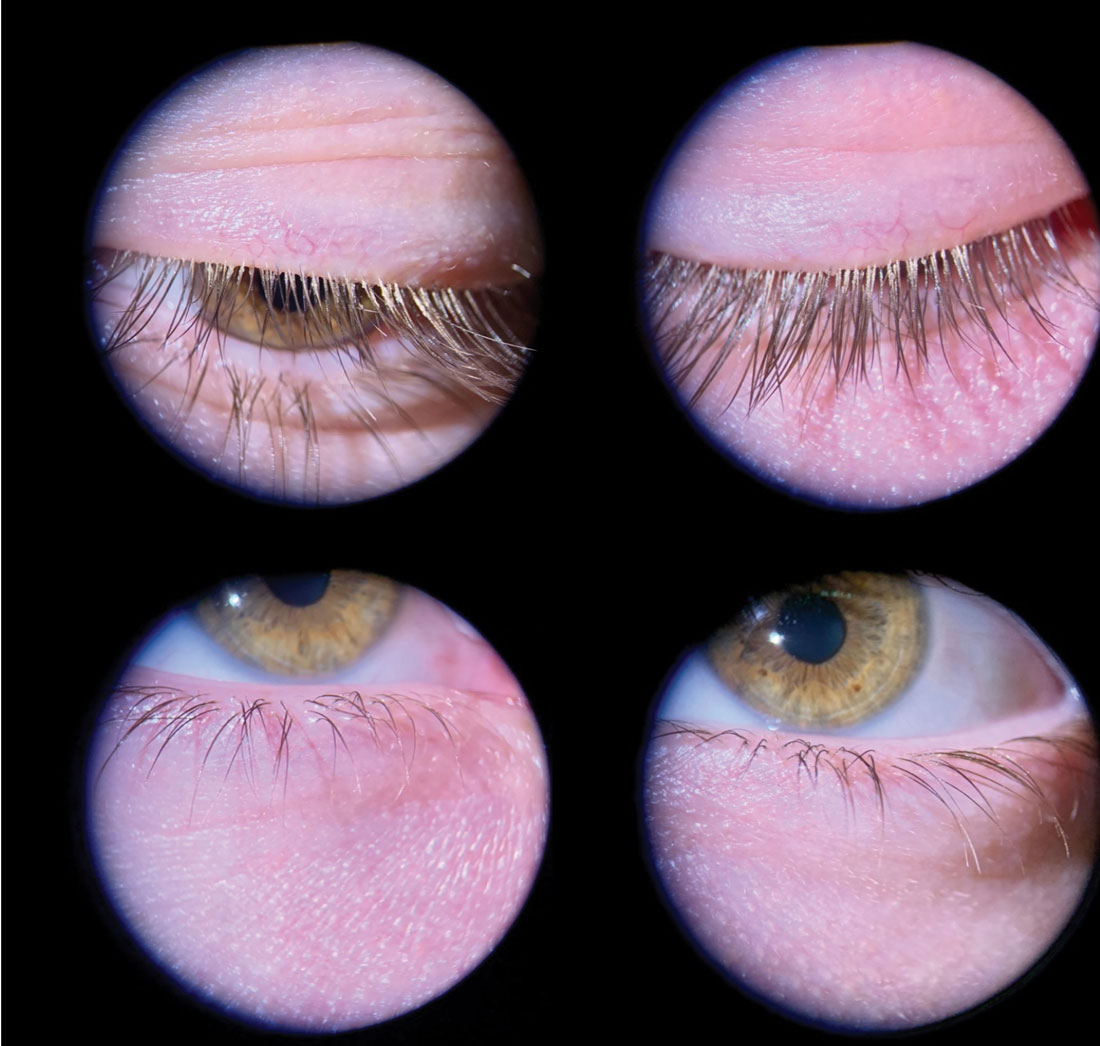

|

Fig. 1. Mild anterior blepharitis in a younger male patient with collarettes at the base of the lashes and mild flaking throughout. Although mild, it is important to treat early to prevent disease progression. This patient undergoes quarterly in-office treatments. Click image to enlarge. |

Chronic blepharitis, which is the most common form of anterior blepharitis, tends to arise from overgrowth of normal skin flora. The healthy lid margin is represented by a stable and relatively limited ocular microbiome, which probably plays a regulatory function for ocular homeostasis. Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus are the most commonly found microorganisms on the eyelids.6 However, the microorganism population can become more diverse in cases of chronic blepharitis.4

The pathophysiology of anterior blepharitis is less related to chronic infection than it is to bacterial overgrowth, and the deposition of biofilms that release inflammation induces exotoxins and lipases along the lid margin.5 This leads to chronic inflammatory responses, increasing telangiectasia, lid hyperkeratinization, folliculitis and decrease in function of the meibomian glands. Due to the close proximity of the lids to the cornea, visible epithelial defects, marginal infiltrates and neovascularization may also be present.

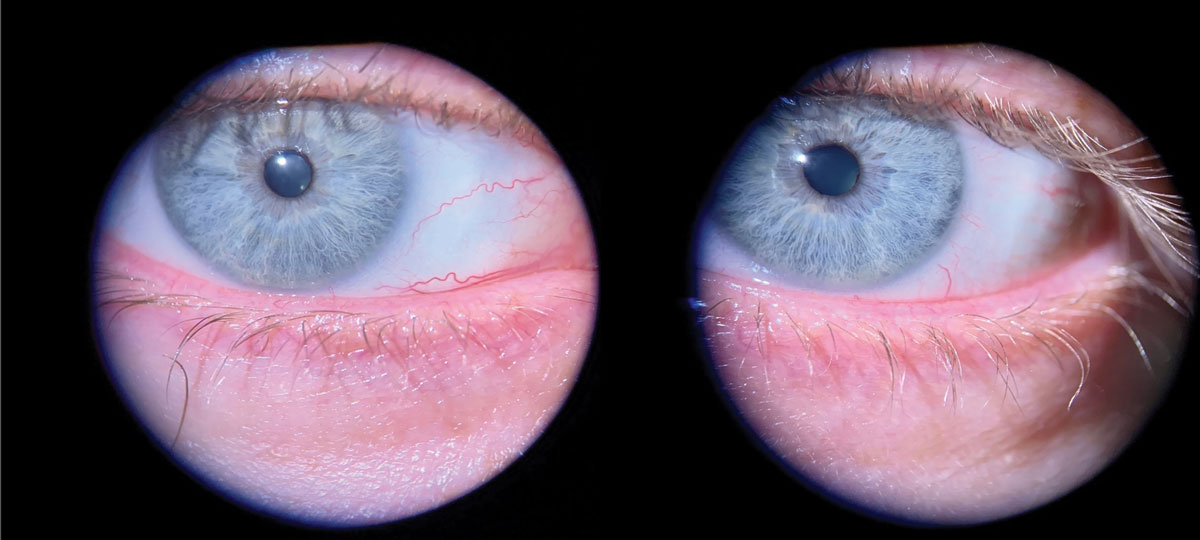

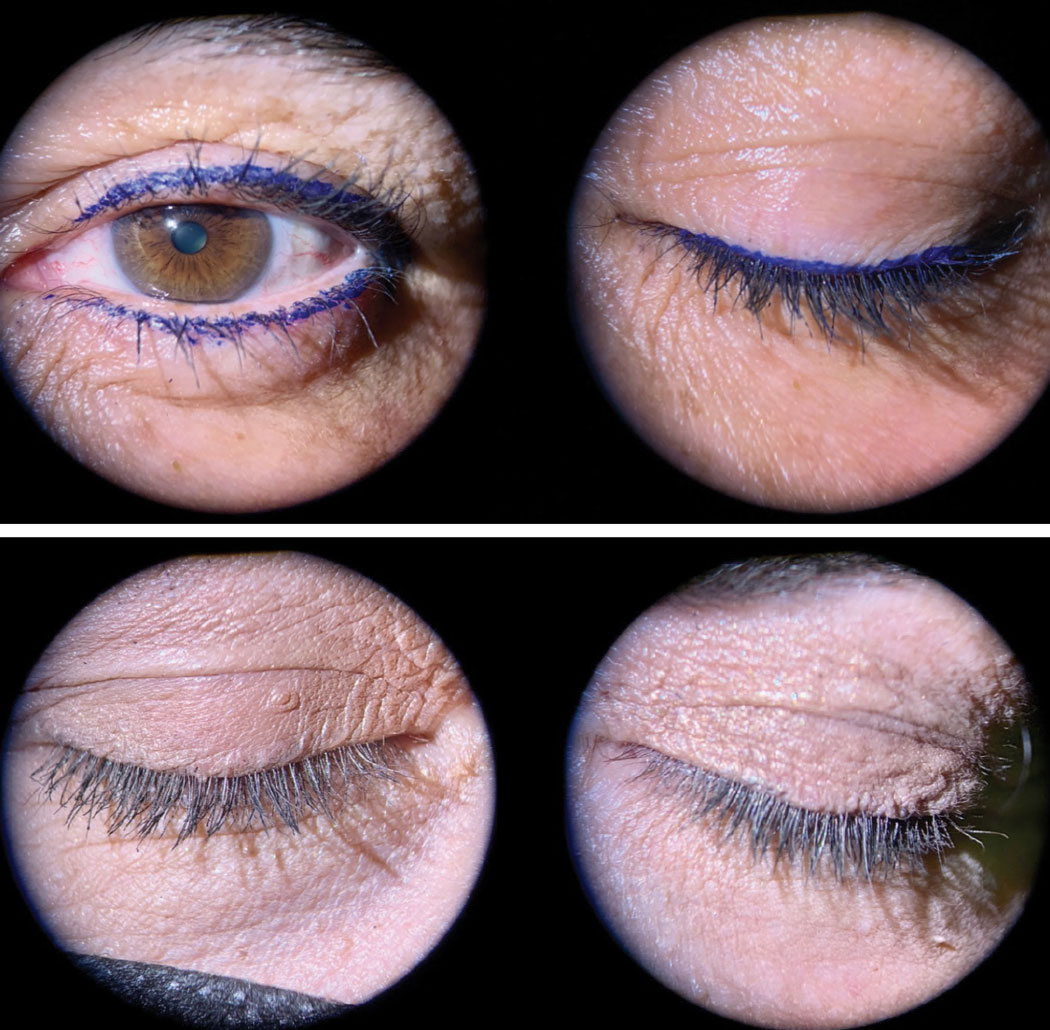

Anterior blepharitis can be further differentiated into the staphylococcal (squamous) form that is typically present in younger patients (Figure 1) and the seborrheic form, which often afflicts older patients (Figure 2), while mixed anterior blepharitis represents a combination of both forms (Figure 3).7 Symptoms for all subtypes include dryness or foreign body sensation, lid irritation or itchiness, burning, loss of eyelashes and lid margin erythema. It should not be overlooked that eyelid disease can be a manifestation of other skin conditions like rosacea, acne or atopic dermatitis, which may need to be treated concurrently—sometimes with the input of a dermatologist. Persistent asymmetric or unilateral disease that is not responsive to treatment should raise suspicion for carcinoma or immune-related lid disease.

|

Fig. 2. Seborrheic blepharitis is visible as the oily-yellow film that has accumulated between the lashes on the lower and upper lids. Click image to enlarge. |

When evaluating blepharitis, the examiner must be mindful to include Demodex infestation in their differential. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are saprophytic mites that normally reside on human skin near the pilosebaceous unit as a commensal organism. The mites can pass between humans through direct contact. While typically harmless, they assume a pathogenic role only when present in high densities (greater than five per lash follicle), resulting in lid inflammation known as demodicosis. Demodex brevis are also associated with rosacea. The mites have a 14-day lifecycle, which starts with procreation and laying eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous gland. They then rely on epidermis and sebum for nourishment. After several weeks, deceased mites decompose within sebaceous glands (D. brevis) or hair follicles (D. folliculorum).8 Demodex infection appears as collarettes at the base of the lashes, very similar to staphylococcal overgrowth, but can be differentiated with microscopic examination.

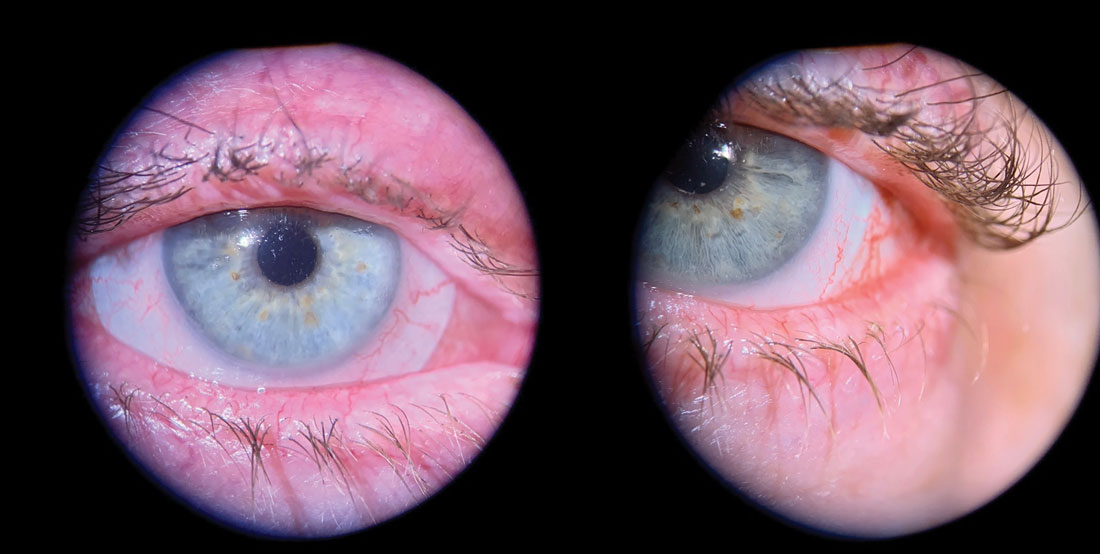

A contemporary discussion about the pathophysiology of anterior blepharitis would not be complete without a nod to cosmetic use (and misuse). The beauty industry offers the public multiple options for lash enhancement including false eyelashes, lash serums for growth, procedures for lash tinting and various makeup options to enhance lash appearance. The false eyelash industry alone is predicted to be a $1.6 billion business by 2025.9 These products often contain harmful chemicals, some of which can induce hypersensitivity reactions or destroy meibomian glands.10 In addition, women often use eyeliner and eyeshadow that soil the eyelid margins, eyelash follicles and clog the meibomian glands (Figure 4).

The cosmetic industry is relatively unregulated and chemicals such as parabens, formaldehyde and phthalates are common ingredients in ocular cosmetics, especially those that are waterproof. These harmful chemicals are often not adequately removed; prolonged contact with the skin can cause damage to the lid margins, meibomian glands and lash follicles. The majority of cosmetic users do not discard their products in a timely manner or wash application brushes regularly, leading to contamination by bacteria, Demodex mites and fungi. Patients who use lash extensions often do not adequately remove applied cosmetics for fear that this will cause the extensions to fall off. Because these habits can exacerbate the disease process and impede treatment, it behooves all practitioners to be familiar with the risks associated with cosmetic use on and around the eyelids as potential contributors to blepharitis.

|

Fig. 3. Advanced blepharitis with lid margin erythema, scarring and telangiectasia. Note areas of missing lashes and lashes clumping in a triangular fashion. Click image to enlarge. |

Determining the prevalence of anterior blepharitis as a solitary clinical entity is challenging. Some of this difficulty lies in the inexact nature of current definitions. To illustrate the difficulty present in the literature, the DEWS II Epidemiology Report variously used the following terms when discussing the prevalence of dry eye: dry eye syndrome, dry eye, keratoconjunctivitis sicca or MGD/abnormalities blepharitis, but not Sjögren syndrome.11 Dry eye disease is known to affect over 16 million Americans, and a large proportion of these patients will have lid margin disease.12 Therefore, while arguably imprecise, it is probably a reasonable marker of blepharitis prevalence as well.

MGD was determined to be the leading cause of dry eye throughout the world at the 2011 International Workshop on MGD, which defined it as “a chronic, diffuse abnormality of the meibomian glands, commonly characterized by terminal duct obstruction and/or qualitative/quantitative changes in the glandular secretion. This may result in alteration of the tear film, symptoms of eye irritation, clinically apparent inflammation and ocular surface disease (OSD).”2

Anterior blepharitis is, however, a separate disease process from MGD, and while many patients suffer from both, the names are not synonymous. MGD is often reported as posterior blepharitis to differentiate the two processes, but these two names are also not interchangeable. Posterior blepharitis is simply an inflammation of the posterior eyelid, but it is not solely related to MGD. Moreover, MGD is not the only cause of dry eye, and narrowly focusing treatment of dry eye on MGD may result in suboptimal outcomes.

|

Fig. 4. Top: Excess makeup at the base of the lashes with eyeliners can increase blepharitis. Bottom: Excess foundation and face powder are often used by some patients to cover lid redness or discoloration. This, with mascara, has left the lashes and lid margins coated with makeup. Click image to enlarge. |

Evaluation

Evaluation of anterior blepharitis is accomplished through slit lamp examination and should be an integral aspect of any comprehensive dry eye evaluation (Table 1).

|

Blepharitis is typically graded on a 0-4 scale but can be further categorized by notating whether it appears to be acute or chronic, whether ulceration or greasy scales are present, whether cosmetics are playing a role and the degree to which eyelash folliculitis or lid margin inflammation are present. Inspection for Demodex mites is done by looking for eggs and lash collarettes. If there is doubt, epilating a lash and placing it on a glass slide with fluorescein will aid in visualization when looking under a light microscope.

One should also note any sequelae of chronic blepharitis, including madarosis, trichiasis, lid margin erythema and telangiectasia, as well as the condition of the line of Marx and any scarring of the lid margins. Slit lamp photography is often crucial for patient education, but also to document interval changes with treatment.

Treatment

Some patients will require an initial pulse of medical management in addition to home therapy. This could include milder topical antibiotics like erythromycin, neomycin/polymyxin-B or azithromycin. Keep in mind that antibiotic-resistant organisms are common and unnecessary over-prescribing increases resistance. A recent study showed that both coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus were often resistant to erythromycin. Some strains were also resistant to penicillin, ciprofloxacin and rifampicin in this same study.6 Bacterial cultures are typically not needed unless the condition is unresponsive to treatment.

When considering medical therapy, recall that anterior blepharitis often has an inflammatory component. When considerable lid margin erythema is present, a two-week course of topical steroid ointments, such as loteprednol or antibiotic/steroid combinations like neomycin/polymyxin/dexamethasone, can be extremely effective. Brand-name drugs can be expensive, so looking for generic options is a responsible way to offer treatment that can also enhance compliance.

When treating anterior blepharitis, the use of ointment or gel formulations is preferred as they will have prolonged contact time with the lids. If solutions are the only available option, then instruct the patient to apply the medication directly to the eyelids with gentle rubbing.

Chronic disease unresponsive to topical therapy may warrant oral antibiotics, like low-dose doxycycline (50-100mg), for their protein denaturing and anti-inflammatory properties. Alternative oral treatment includes a pulse of oral azithromycin 500mg for three days, then off for four days and repeated for a total of four weeks. As stated earlier, anterior blepharitis does not represent an infection with a pathogenic microorganism; rather, it is the toxic byproducts of normal bacterial biofilms present on the lid margin. It is important for patients to realize that medications are to augment home therapy and will not eradicate the problem alone.

If Demodex mites are found, their elimination can be accomplished using tea tree eyelid shampoo formulations or hypochlorous acid (HA) products; however, long-term prospective studies are lacking.13 A recent paper suggested that tea tree oil may be harmful to meibomian gland epithelial cells in vitro.14 Intense pulsed light therapy and oral ivermectin are alternative options for treatment.15,16

In-office comprehensive eyelid cleaning programs are an excellent strategy for quickly and efficiently getting ahead of anterior blepharitis and providing patients instructions about proper at-home procedures. Semi-annual cleanings performed in-office is a reasonable approach, but adoption will be patient-dependent. Patients with poor vision, limited dexterity, cognitive impairment/dementia or who are averse to touching their eyes may need to be seen more frequently. Women who habitually get lash extensions should come in for a comprehensive cleaning between applications to remove glue, lashes, desquamated epithelium and cosmetic residue. Patients with anterior blepharitis should have a comprehensive cleaning before any surgical consultation.

In terms of patient education regarding cosmetic use, some practitioners may simply tell them to stop using makeup, but most individuals will not be willing to do so. However, educating patients about the deleterious effects of some cosmetic ingredients in a non-patronizing way is usually appreciated if done properly. It can be more prudent to provide tips on application, placement and removal of periocular cosmetics, and even recommend dry eye–friendly product lines, such as Èyes Are the Story, that improve patients’ appearance by reducing inflammatory reactions to these chemicals.

Home Care

Despite the realization that vision is one of the most vital senses in everyday life, ocular personal care is often completely neglected by patients. Part of this problem is the reactive nature of the eye care profession, which has failed for decades to impart the necessity of preventative eyelid health, starting in middle school.

|

In our practice, the dental model is invoked as an analogy, since this is a concept relatable to patients, even at an early age. A consistent message for every patient, at every visit, should include a recommendation for routine home care with intermittent office visits for more in-depth cleaning if required. This is analogous to brushing one’s teeth at home and having intermittent cleanings in the office. Frequency of home care can be tailored to the severity of the condition. This can vary from lid cleaning a few times per week in milder cases to twice daily in more advanced cases of blepharitis or for regular heavy makeup wearers. Fortunately, unlike warm compress therapy, which is notorious for patient non-adherence, eyelash cleaning is simpler and quicker, and tends to be better accepted by patients.

When introducing a patient to a home care routine, it is very important to outline a schedule, provide written instructions and spend the time demonstrating the techniques in the office (Table 2). This will increase patient compliance and lead to more successful clinical outcomes. First, recommend the type of product you wish the patient to use. Long gone are the days of saline, mineral oil or diluted baby shampoo as the only options for lid hygiene. Industry has responded to data showing that eyelid hygiene is an effective method to treat anterior blepharitis and eyelid disease in general, including dry eye.

|

Fig. 5. Doctor using BlephEx electronic cleaning system on upper and lower lids during in-office cleaning. It is important to get both the lashes and the lid margin, including the meibomian gland orifices during the treatment. Click image to enlarge. |

A plethora of new safe and effective products are available. In broad terms, these can be classified as surfactant/soap, tea tree oil or HA-based products. All three categories have different brands and concentration levels, so it is best to familiarize yourself with these and curate those products in which you have confidence. Patients with sensitive skin should be started at lower concentrations of the active ingredient to better monitor for adverse events. Tea tree and HA products are recommended if a concurrent infestation with Demodex mites is present.

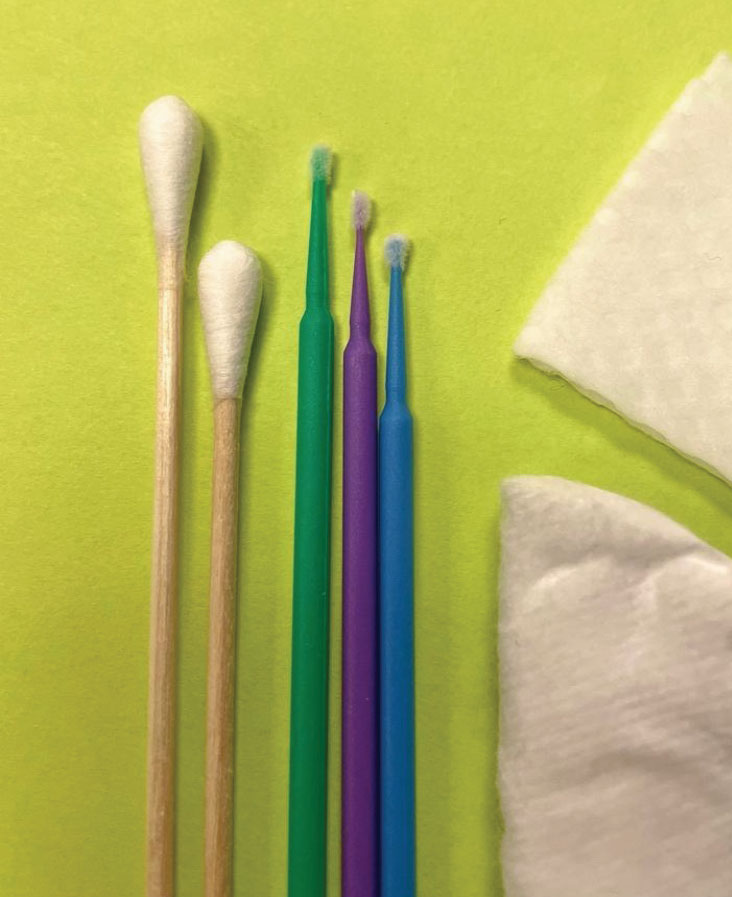

After selecting the cleaning product, it is very important to recommend a type of applicator (Figure 6). Several products on the market can be sprayed onto the lids, but we recommend lightly scrubbing the lid margin and lashes. For the same reason, manual rubbing of contact lenses is recommended, effective removal of debris is best accomplished with physical contact. Cotton-tipped applicators are most often used. Medical-grade options are stiffer and the cotton is less likely to whisp off into the eye. Bristle brushes, created for applying lash extensions, can be helpful for hard-to-remove biofilms and makeup. Cotton rounds or pre-moistened pads are best for patients without the vision or dexterity to manage other options. With young children or patients who find it difficult to find time to “do that one extra thing,” current products can be applied in the shower. Electric versions with disposable tips, like an electric toothbrush, are available (e.g., NuLids). (Figure 7).

|

Fig. 6. Cleaning tools that can be used for home or office cleaning. Cotton-tipped applicators, bristle brushes and makeup rounds that can be moistened with various products. Pre-moistened towelettes are also available. Click image to enlarge. |

Having staff members demonstrate the techniques of eyelid and lash cleaning is key to long-term success. Pitfalls that will derail your home therapy recommendations include: patients closing their eyes so tightly that they cannot access the junction of the eyelid and lash, development of a contact dermatitis because they did not understand that washing off the cleaning solution was necessary and cleaned the palpebral conjunctiva instead of the lid margin and base of the eyelashes.

Patients with concurrent MGD can get confused about whether cleaning should be done before or after warm compress therapy. Some patients prefer to do it before to remove dirt, debris and makeup so the oil can escape the glands once heat is applied. Others prefer to complete lid maintenance after the warm compress since the debris is often loosened and easier to remove. Either option is viable, if the proper technique is used.

With lash hygiene, the target is the base of the lashes where oil can accumulate or Demodex can form collarettes, as well as the space between the lashes, where a film and desquamated epithelium and/or cosmetics can accumulate. Lid margin scrubs aim to clear slightly posterior to this at the orifices of the meibomian glands and the mucocutaneous junction (line of Marx). Cotton-tipped applicators can be held like a pencil and run across these two areas, similar to makeup application. On the upper lid, it should be done with the eye closed and while everting the upper lid slightly (Figure 5).

|

Fig. 7. Patient using NuLids electronic lid cleaning system on lower and upper eyelids for at-home cleaning. Click image to enlarge. |

Practice Management

As previously discussed, anterior blepharitis is rarely found in isolation and is often part of the multifactorial constellation of dry eye disease. Therefore, diagnosis and treatment are often pursued in conjunction with other management recommendations. Dry eye treatment is poised for continued growth, with revenues estimated to reach $6 billion globally by 2023.17

Many practitioners become overwhelmed when they try to do too much during a comprehensive eye exam. Annual exams, much like routine physicals, are meant to screen for ocular pathology. When abnormal results are found, the patient returns for more testing, monitoring or treatment. For example, if a patient has an abnormal intraocular pressure or cup-to-disc asymmetry, they are instructed to return for a glaucoma work-up. When treating anterior blepharitis this same approach should be followed.

Too often, this very common condition is undertreated or not treated at all because the proper time is not allotted to educate the patient and control the problem. Left untreated, it becomes a larger project requiring greater resources. In addition, because of the significant association of anterior blepharitis with MGD and Demodex mite infestation, a more thorough examination looking for these comorbidities is often warranted.

In-office cleanings are not covered by insurance but nevertheless represent a common-sense and efficient strategy for initial treatment of the patient with chronic anterior blepharitis. Regardless of insurance coverage, all testing and in-office treatments should be documented with a CPT code. BlephEx and lid cleaning procedures do not currently have a CPT code, so 92499 (unlisted ophthalmological service or procedure) should be used.18 Patients should always be provided with an Advanced Beneficiary Notice to outline testing and treatments that may be reimbursed by their insurance and those for which the patient may be responsible.

|

Fig. 8. Superior lid margins and lashes of the same younger male patient (Fig. 1) after comprehensive in-office lid cleaning. Click image to enlarge. |

Takeaways

As our knowledge of OSD expands, it’s important to remember it is a multifactorial disease that requires comprehensive recommendations that address each contributing factor. This typically includes patient education and a foundation of home therapy with lid and lash hygiene, warm compresses, blinking exercises and lubricating tears or meds as needed.

In addition, lifestyle modifications especially with respect to cosmetic use are necessary. Invoking the dental model of preventative and restorative care should be pursued with regular office visits and therapies used in conjunction with home care for increased success. Patients should be reminded that blepharitis and dry eye are both chronic in nature and require their ongoing participation for self-care. Long-term prevention and maintenance, rather than reactive therapies, requires a change in mindset for practitioners and patients alike.

Dr. McLeod is a partner at Korb & Associates in Boston, MA. Most recently, he was an associate professor within the department of specialty and advanced care and chief of the Cornea & Contact Lens Residency at New England College of Optometry (NECO). He has no financial disclosures.

Dr. Nau is a partner at Korb & Associates and an adjunct associate clinical professor at the NECO. She is on the advisory board for Oyster Point and a speaker for EyeEco. The two are Fellows of the American Academy of Optometry and members of the American Optometric Association and the Massachusetts Society of Optometrists.

1. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):276-83. 2. Nichols KK, Foulks GN, Bron AJ, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Mar 30;52(4):1922-9. 3. Aumond S, Bitton E. The eyelash follicle features and anomalies: A review. J Optom. 2018;11(4):211–22. 4. Krachmer, JH, Mannis, MJ, Holland, EJ. Cornea: fundamentals, diagnosis and management. 3rd Edition, Elsevier Inc. 2011. 403-5. 5. Pflugfelder, S, Bauerman, R, Stern, ME. (2004). Dry eye and ocular surface disorders (1st ed.). CRC Press. 255-7. 6. de Paula A, Oliva G, Barraquer RI, de la Paz MF. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated in patients affected with blepharitis in a tertiary eye centre in Spain. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;30(5):991-7. 7. Duncan K, Jeng BH. Medical management of blepharitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):289-94. 8. Rather PA, Hassan I. Human demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):60-6. 9. Website: False eyelashes market size worth $1.6 billion by 2025. Grandview Research. Accessed 10/2021. 10. Chen X, Sullivan DA, Sullivan AG. Toxicity of cosmetic preservatives on human ocular surface and adnexal cells. Exp Eye Res. 2018;170:188-197. 11. Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334-65. 12. Ferrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IO, Schaumberg DA. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;182:90-8. 13. Savla K, Le JT, Pucker AD. Tea tree oil for Demodex blepharitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6(6):CD013333. 14. Chen D, Wang J, Sullivan DA, et al. Effects of Terpinen-4-ol on meibomian gland epithelial cells in vitro. Cornea. 2020 Dec;39(12):1541-6. 15. Fishman HA, Periman LM, Shah AA. Real-time video microscopy of In Vitro Demodex death by intense pulsed light. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2020;38(8):472-6. 16. Holzchuh FG, Hida RY, Moscovici BK, et al. Clinical treatment of ocular Demodex folliculorum by systemic ivermectin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(6):1030-4.e1. 17. Dalton M. Understanding prevalence, demographics of dry eye disease. Ophthalmology Times. 2019. 18. Rumpakis J. Ocular Surface Coding Potpourri. Rev Optom. 2015. |