Seeing optic disc edema can be quite alarming. The causes are more serious in nature, and vision loss associated with optic disc edema can sometimes be permanent—not to mention that some causes can be life-threatening. If possible, the immediate reaction most times will be attempting a referral to neuro-ophthalmology; however, it can be very difficult to find a specialist who accepts same-day referrals. Some are booked for weeks or months ahead of time. Many optometrists don’t feel comfortable working up these types of cases, but some are true emergencies and need to be sent to the hospital anyway.

This article will focus on identifying various presentations of unilateral and bilateral disc edema, knowing the most common causes and making hospital ED referrals with good doctor-to-doctor communication to ensure the appropriate patient work-up.

Common Causes

In general, the more common causes of disc edema that present to our offices are either non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) or papilledema.

NAION. The typical presentation is sudden, painless vision loss in one eye and usually noticed upon awakening. Patients are typically 50 years of age or older. NAION affects males more than females and those with preexisting microvascular disease. However, it can still occur in those younger than 50 and even in patients without vasculopathic risk factors. Visual acuity can be variable but is not significantly affected, with 49% of NAION cases presenting with 20/30 vision.1 Visual field defects are almost always either altitudinal or arcuate type deficits.

The disc edema associated with NAION can be either sectoral or diffuse and generally has a hyperemic appearance to it.1 The fellow optic nerve will almost always have a “disc at risk” appearance with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3 or less.1

AION. This by far is much more concerning than NAION and will oftentimes have a much different presentation, although there can be some overlap with signs and symptoms. It is critical, however, to try and differentiate these two disorders clinically. Patients will typically be 50 years of age or older; in our experience, we typically see this in those between their 60s and 80s. Females are affected more than males.

Systemic symptoms will generally be present but not 100% of the time, with potential patient complaints of headache, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, fatigue, weakness and/or myalgias. Patients may have had episodes of amaurosis fugax prior to vision loss. The loss will generally be much more severe when compared with NAION, usually presenting with worse than 20/400 vision.

The disc edema seen in AION will generally have more of a pallid swelling appearance vs. the hyperemic appearance seen in NAION.2 Additionally, cotton wool spots and or retinal artery occlusion can also be seen.2

Papilledema. By definition, papilledema is bilateral optic disc edema secondary to increased intracranial pressure (ICP).3 Because of the various causes for the condition, it can be seen across all age groups.

If the elevated intracranial pressure exceeds the intraocular pressure, there will be an absence of the spontaneous venous pulse.4 This discs will usually be hyperemic, have hemorrhages and Paton’s lines can sometimes be seen (retinal folds within the peripapillary region).4 Acuity can range anywhere from 20/20 to almost total vision loss. Sometimes, a patient won’t present initially or will wait until very late into a disease process to the point where their vision is significantly impacted on first presentation. Visual field defects can have great variability as well.

Additionally, a variety of patient symptoms can be present depending on the cause of the papilledema. Visually, patients can describe reduced acuity, transient vision loss or transient visual obscurations. Diplopia may be present as cranial nerve VI palsies can be seen in association with papilledema but, depending on the etiology, other cranial nerves can be affected as well.

Generalized neurologic symptoms can also vary greatly and can include headache, dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, vomiting, altered consciousness and fever.5

Diagnosis and Management

After describing the more common causes of disc edema and what distinguishes each one, let’s discuss what to do when presented with someone who has disc edema. In addition to doing a complete dilated examination, visual fields and optic nerve photos are a must for baseline and future comparison.

The visual field can also be exceptionally helpful for diagnostic or possibly localization purposes. For example, patients with NAION will often have an altitudinal field defect. The next step then depends on whether the disc edema is unilateral vs. bilateral.

Bilateral. With bilateral disc edema, there is a good chance that it is secondary to increased intracranial pressure.

First, check the patient’s blood pressure. Malignant hypertension can cause papilledema and it’s quick and simple to measure. There will be other retinal findings of hypertensive retinopathy, and if the blood pressure is significantly elevated (>180/>110), then it’s likely the answer to the disc edema. Malignant hypertension is a medical emergency, and these patients need to be sent to the emergency department (ED) for immediate work-up and treatment of their blood pressure.

Neuroimaging will sometimes be done in the general work-up of malignant hypertension, and we suggest recommending brain imaging be done in this scenario just to completely rule out any other cause of the disc edema. Once this diagnosis has been established, it’s a matter of stabilizing the patient’s blood pressure and serial monitoring of the disc edema, retinal findings and visual fields for improvement.

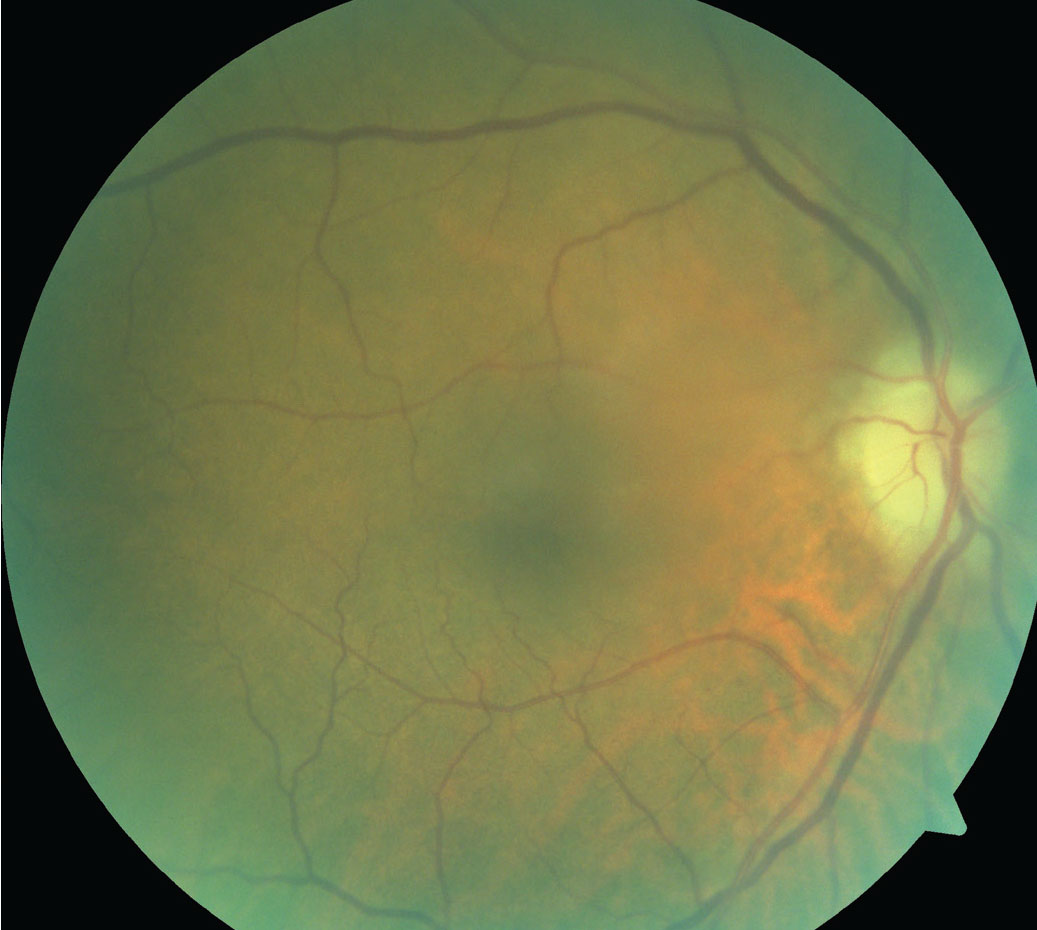

|

| Note the hyperemic disc edema in this patient presenting with NAION. Click image to enlarge. |

If the blood pressure is normal or at least not high enough to consider malignant hypertension as a cause, the second question to ask yourself is whether the patient and presentation seem consistent with pseudotumor cerebri (PTC). The characteristic presentation will be a younger female between the ages of 20 and 40 who is either overweight or taking medications associated with PTC. Such meds include: lithium,vitamin A and derivatives such as Accutane (isotretinoin, Roche) and tetracyclines.6 The classic symptoms include headache, transient visual obscurations, tinnitus and nausea.6

In a situation where the patient’s demographics, symptoms and clinical findings all point towards PTC, we recommend first performing a visual field in office. Although PTC in itself generally isn’t an emergency, the diagnosis cannot be confirmed until imaging has been performed and deemed normal and lumbar puncture shows an opening pressure of greater than 25cm H2O. Until then, it’s still a patient with papilledema of unknown cause and should be treated as an emergency. Because of that uncertainty, we suggest sending these patients to the ED, recommending neuroimaging, such as a computerized tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance venography (MRV), to rule out any mass or intracranial process and, if they come back normal, recommending a spinal tap with neurology consultation for PTC.

Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, neurology will generally manage reducing the intracranial pressure. Monitor the patient’s fields, usually on a monthly basis. Assuming no significant or progressive field deficits are present, management will consist of weight loss, starting a diuretic such as acetazolamide and/or discontinuing any predisposing medications mentioned previously. However, in more severe cases with significant vision or field loss, treatment will require a more aggressive approach such as ventriculoperitoneal shunting or optic nerve decompression. These decisions are usually made by the neurologist after interpreting the extent of the vision and field loss and, if necessary, at that point they would request neuro-ophthalmology evaluation.

Lastly, if we see papilledema in this patient, there is no malignant hypertension and the patient doesn’t fit the profile for PTC, then there is likely a very serious pathology causing the disc edema. These patients will always be sent to the ED and with much more concern for some intracranial process. Emergent neuroimaging and depending on the findings neurology and or neurosurgery consultations will generally be recommended.

One clinical pearl to keep in mind is that bilateral disc edema won’t always be secondary to elevated intracranial pressure/papilledema. For example, a patient with bilateral AION from giant cell artheritis (GCA) may present with bilateral disc edema. Take into account all pertinent historical elements, findings and patient demographics to help determine if the likely cause of the bilateral disc edema is from elevated ICP or some other process. In general, brain and orbit imaging along with GCA testing will almost always identify the abnormality and if normal, other serologic testing or lumbar puncture is usually the next step.

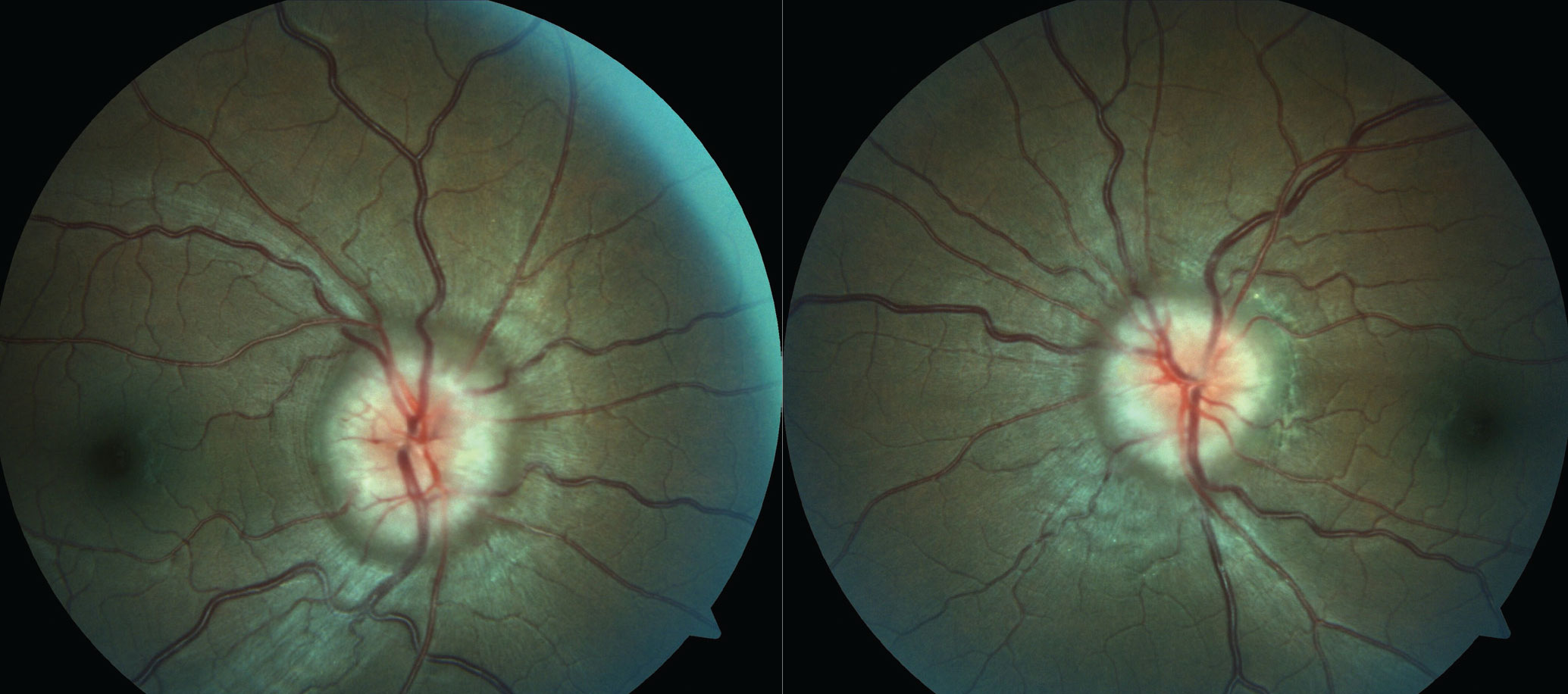

|

| Note the pallid disc edema in this patient presenting with AION. Click image to enlarge. |

Unilateral. In addition to NAION and AION, unilateral disc edema can be seen from tumors or anything that would cause optic nerve compression, optic nerve infiltration (i.e., sarcoid, lymphoma) and optic neuritis (more common to be retrobulbar but can present with disc edema). Vision loss from a compressive or infiltrative process tends to be a bit slower in onset—usually days to weeks to months vs. NAION and AION, where the vision loss is sudden.

Optic neuritis can present with acute vision loss, but it’s typically associated with pain, especially during eye movement. A major distinguishing feature between painful vision loss from optic neuritis vs. painful vision loss from AION is age. Optic neuritis is more typical for younger patients while AION is typical for older patients. Additionally, vein occlusions will commonly cause disc edema, but these are very easy to identify because of the retinal hemorrhages associated with the disc edema. Lastly, neuro-retinitis will also cause disc edema, but usually in association with other findings such as macular exudates, uveitis and vascular sheathing.

Disc edema from a vein occlusion can almost always be easily spotted and these patients do not requite any neurological work-up. And the remaining causes can be frequently identified with neuroimaging, basic serology testing and, when indicated, lumbar puncture. So, with this in mind, if you are presented now with a case of unilateral disc edema and can’t find an immediate referral source or if you’re not comfortable with working up these patients yourself, ED referral is still a great option.

If an AION is suspected, evaluate the patient for GCA. Checking ESR, CRP and also looking at the patient’s platelets would be the first step. Rheumatology can also be consulted to further evaluate for GCA.

In regard to patients with suspected NAION, there is debate on whether or not these patients need to be imaged initially. Some doctors feel that if the presentation is consistent with NAION, they can be followed initially without imaging and only recommend testing for GCA if the patients are older with any suspicion. There is no standard of care rule on this and we’ve seen optometrists, ophthalmologists and neuro-ophthalmologists on both sides of the fence. We personally feel it’s in the patient’s best interest, even when very confident that the diagnosis is NAION, to obtain at least an ESR and CRP as well as neuroimaging.

Even if you are presented with a case that points towards NAION but are not comfortable with following initially or managing yourself and can’t find a timely outpatient referral, it is still acceptable to send even these patients to the ED. Emphasize with good communication that the patient has a likely NAION, but you would suggest at least testing ESR, CRP and neuroimaging to rule out any other causes. Additionally, patients with NAION need to ensure their microvascular disease is under appropriate control. In cases of NAION where no obvious microvascular risk factors exist, such as diabetes, hypertension and sleep apnea, patients will often need hypercoaguable and autoimmune work-ups.

If the suspicion of disc edema points towards optic nerve compression, infiltration, inflammation or demylenation, the focus will be largely on neuroimaging and possibly lumbar puncture. These specific decisions don’t need to be made by the optometrist, but communicating these suspicions and any guidance is important when sending these patients to the ED. For example, if optic neuritis is suspected, recommended that the patient eventually have a brain and orbit MRI and not just a CT scan, as the CT is usually not sensitive enough to detect those findings.

Also, when referring patients like this, a recommendation for neurology consultation should almost always be made. The on-staff neurologist will also help to guide the appropriate work-up if necessary.

|

| In this patient with papilledema secondary to PTC, the diagnosis cannot be confirmed without normal MRI/MRV and after lumbar puncture has been performed. Click image to enlarge. |

Takeaways

Being on staff and working at a hospital, we see referrals such as these commonly. We’ve never seen an ED attending get upset over this type of referral as long as the exam findings and recommendations are properly communicated. A doctor-to-doctor phone call describing the pertinent findings and recommendations, as well as a detailed letter handed to the patient, seems to be the best approach.

This is especially true if you are sending the patient to a hospital that doesn’t have an optometrist or ophthalmologist on staff. In general, if you are going to make this type of referral, it’s best to find out which hospital closest to you has these providers on staff. If they do not, it just makes your communication of the findings and recommendations all the more critical.

Additionally, optic nerve photos and visual field results are equally as important as communicating your findings. Almost every optometry office these days is equipped with both and it’s just another layer of data for the ED staff to have. Otherwise, these work-ups are usually done on blind faith of the findings communicated to them. Although most ED rooms are equipped with an ophthalmoscope, it’s rare to find a hospital staff proficient in using them. Even if your office is mostly electronic and it’s difficult to print out field or fundus photos, a simple picture taken and texted to the patient is extremely helpful.

While neuro-ophthalmology is always the first option when presented with cases like this, when that’s not available the hospital setting can be an equally effective and, many times, a necessary alternative. As long as proper communication exists between the optometrist and hospital staff, work-ups can certainly be guided in the right direction. Testing and specialty consultations can all be done within the same facility aiding in good doctor-to-doctor communication and also will be performed in the fastest and most efficient manner.

1. Berry S, Lin WV, Sadaka A, Lee AG. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: cause, effect and management

2. Hayreh SS. Management of ischemic optic neuropathies. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011; 59(2):123-36.

3. Rigi M, Almarzouqi SJ, Morgan ML, Lee AG. Papilledema: epidemiology, etiology, and clinical management. Eye Brain. 2015;7:47-57.

4. Choudhari NS, Raman R, George R. Interrelationship between optic disc edema, spontaneous venous pulsation and intracranial pressure. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57(5):404-6.

5. Whiting AS, Johnson LN. Papilledema: clinical clues and differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 1992;45(3):1125-34.

6. Burkett JG, Ailani J. An up to date review of pseudotumor cerebri syndrome. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18(6):33.