|

Brian’s fourth concussion had put him out of professional hockey for about a year, and he wondered if his NHL career might be over. Looking for help, he reached out to Sue Durham, OD, who was an officer of the Neuro-Optometric Rehabilitation Association at the time. Dr. Durham prescribed Brian glasses with low plus and a small amount of cylinder. The lenses helped him begin his recovery, but he was ultimately referred to us with the goal of getting back on the ice.

The Problem

When Brian presented, he reported improvement with his glasses—but not without a few hitches. While they allowed him to drive, play with his children and start exercising again, if his heart rate passed 100 beats per minute he had to lie down on the couch to rest. Watching television and looking at a computer screen caused similar types of visual overload.

|

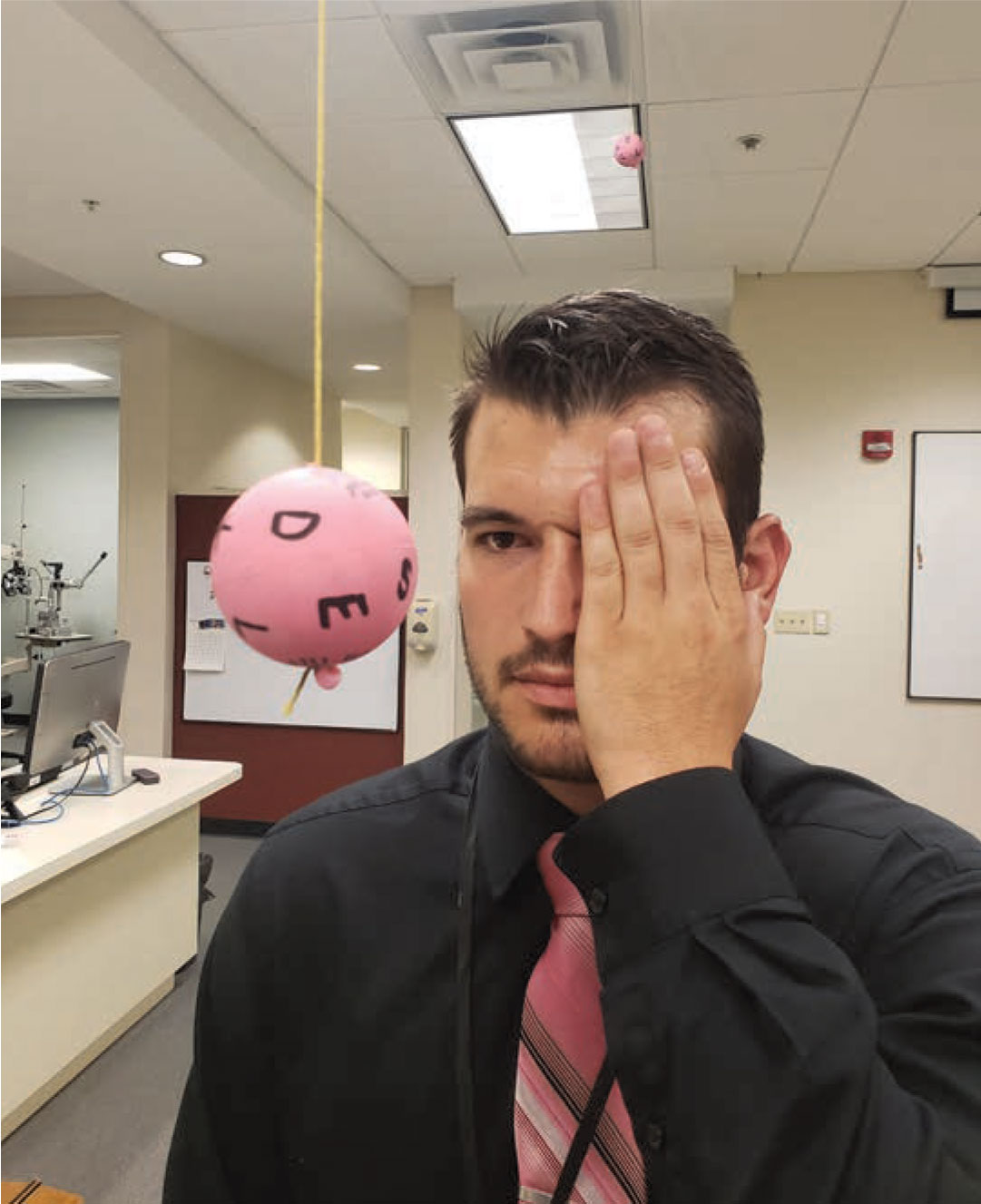

| After a few rounds of vision therapy, Brian was able to return to the ice. Click image to enlarge. |

Brian moved in a very guarded way, keeping his head locked with his torso and rarely moving his eyes away from primary gaze. To look from one thing to another, he turned his entire body, or he just didn’t look at all.

Brian saw clearly, at least 20/15 OD, OS and OU with and without glasses. We proceeded with chair testing with the glasses. Stereo, color, near point of convergence and other tests in the standard battery were all normal. The refractive elements of the exam confirmed that the glasses did indeed offer maximum visual acuity and comfort. However, the analytical data, including the base-in and base-out ranges at distance and near, told a different story.

Brian’s base-out breaks were greatly reduced at both distance and near. At distance, the base-out break was three instead of 19; at near, it was six instead of 21. Though base-out prism ranges measure convergence in response to a prismatic challenge, they could also indicate a general stressor, which Brian gave into when challenged. These are not the kind of numbers we typically see with elite athletes who switch into higher gears when the going gets tough. But they did match his complaints of fogginess and fatigue. He had not been on the ice since his fourth concussion because he found it too overwhelming and overstimulating.

The Solution

It is common for people to alter their daily routine to get back to a successful life after suffering an injury. Brian had done this by avoiding the things that caused him to suffer the symptoms secondary to his traumatic brain injury. But we were over a year out from the injury and surely his brain had recovered, so why was he still having all these symptoms? The answer was in his guarded, unnatural movements.

Most people have smooth, accurate eye movements, unencumbered by having to carry out those movements by moving the whole body. The body acts as a platform to allow the visual system its freedom of movement to collect the space-time data it needs to direct the athlete to achieve a certain level of performance. When the eyes are held steady in the head and the head is held steady on the body so that ocular movements are made with the whole body, all precision is lost and we are forced to overcompensate. This excess effort leads to overstimulation and overload, causing the brain to react and preserve overall health. Thus, the symptoms Brian suffered were protective and telling him to minimize these actions.

|

| The Marsden ball was one of the most important parts of Brian’s vision therapy. Click image to enlarge. |

The first thing I (Dr. Harris) realized was that we couldn’t do anything more with glasses. What Brian needed was vision therapy. The main goal of his therapy was to reestablish normal movement patterns. A key activity was the Marsden ball held inches from his face that he had to track in two different ways—what we call the Greenwald Eye Movements. The first involved him moving his eyes without moving his head. We started out with him lying on the ground with the ball just clearing his nose while moving from side-to-side. Next, he had to track it by moving his head without moving his eyes. Once he mastered this lying down, we then moved from a seat with a back to a seat without a back to standing on both feet to standing on one foot. It took several sessions to work through these patterns.

Since Brian’s commute was about 75 minutes each way to our practice, we scheduled 90-minute sessions. I was surprised when, at the end of the second session, he asked if he could begin cardio work. His team physician and athletic trainer deferred to me, and I told him to go for it. At the beginning of the third session, he stated he could now get his heart rate up to well over 120 without experiencing any adverse symptoms. After the fourth session, he began practicing on the ice once more. He progressed so quickly that, by the end of the sixth session, he was cleared to play again by the head physician of the NHL Players’ Association.

Brian returned just in time for his team to make a run at the playoffs. We watched on TV as he successfully cleared loose pucks from the goalmouth and made beautiful vertical passes up the ice to hit the tape of a teammate skating at full speed who was then able to make a play on the offensive end. It was clear that our hard work had paid off.

Early on after Brian’s fourth concussion, he learned to move in a more guarded way to avoid triggering symptoms of the traumatic brain injury he had sustained, but this caused other symptoms instead. Vision therapy helped restore Brian’s natural movements by recalibrating his vestibular system. Once he started moving more fluidly and naturally again, his system was able to process visual input much more efficiently without overloading and overwhelming him.