|

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) has long challenged eye care professionals, particularly due to its chronicity. This bilateral, allergic inflammatory disease is often labeled as seasonal, despite the fact that patients frequently have recurrences throughout the year—often with serious consequences, including loss of vision.1 Management of VKC must be continuous with a heavy emphasis on patient education, focusing on prompt treatment for acute exacerbations.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

VKC generally first presents at an early age—usually between ages four and seven—but it can manifest in infancy.2 Although it usually resolves after puberty, VKC is also sometimes seen well into adulthood.3,4 In fact, although adults with VKC demonstrate the same clinical manifestations, the inflammatory response tends to be higher, which increases risk of fibrotic sequelae.5 In either case, VKC primarily (thought not exclusively) affects young males who live in arid climates, leading some researchers to believe that it may involve a genetic predisposition.2

Occasionally, VKC is associated with atopy, implicating a host of environmental factors such as wind and pollen.2,6 However, it’s often said that the term “vernal” is a misnomer since about 23% of cases are perennial and nearly 16% of seasonal cases evolve into a perennial variant in a mean of three years’ time.7 Furthermore, research shows that as many as 60% of VKC sufferers have had a recurrence during the winter months.7

|

|

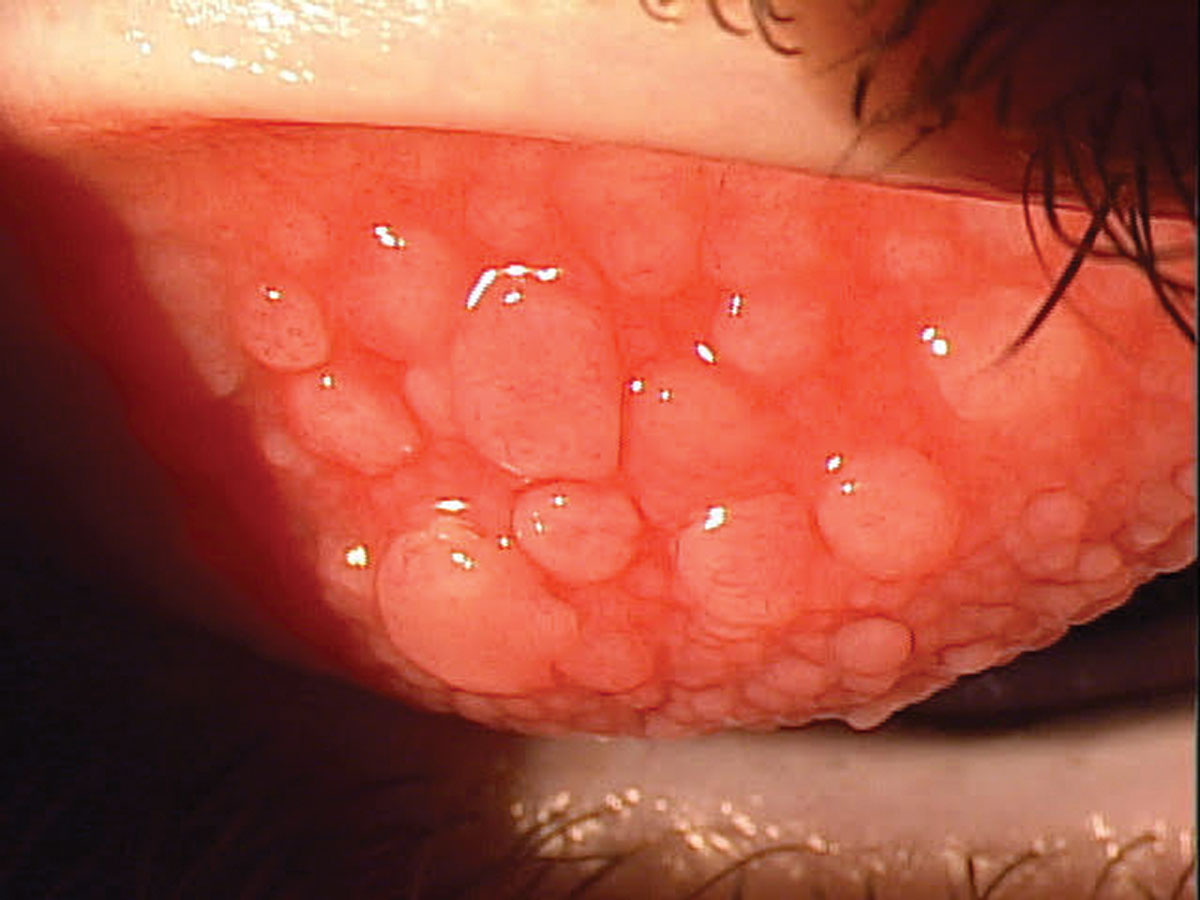

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis before treatment started. Management of this condition and long-term care is essential, as recurrence is a top concern. Click image to enlarge. |

Signs, Symptoms and Classification

Clinical signs, symptoms and medical history are far more useful in guiding VKC diagnosis than other tests, such as skin prick.2 VKC is classified according to the part of the conjunctiva predominantly involved—bulbar/limbal, palpebral or mixed. In most cases, the disease primarily involves the tarsal and bulbar conjunctivae.3 Papillary hyperplasia can range in size from 0.1mm to 5mm, sometimes with a cobblestone appearance.8

In the case of limbal VKC, you’ll likely note opaque, gelatinous confluent papillae and Horner-Trantas dots.3 Many VKC cases are misdiagnosed as allergic conjunctivitis because the signs, such as eosinophilic elevations, may only involve one or two clock hours of the limbus. The number of cases would likely be higher if clinicians closely observed the limbus in all children presenting with severe ocular allergic reactions.

Be on the lookout for ropy discharge, conjunctival congestion and even corneal involvement in severe cases. Patients will likely complain of itching, discharge, watery eyes, photophobia and foreign body sensation. Keep in mind that the itching can be debilitating and complaints about pain and extreme light sensitivity should alert you to potential corneal involvement.2

Recurrence is a top concern since it can result in complications, including keratoconus, shield ulcers, chronic dry eye, limbal stem cell deficiency and lid complications due primarily to chronic inflammation, eye rubbing and long-term steroid use.2

|

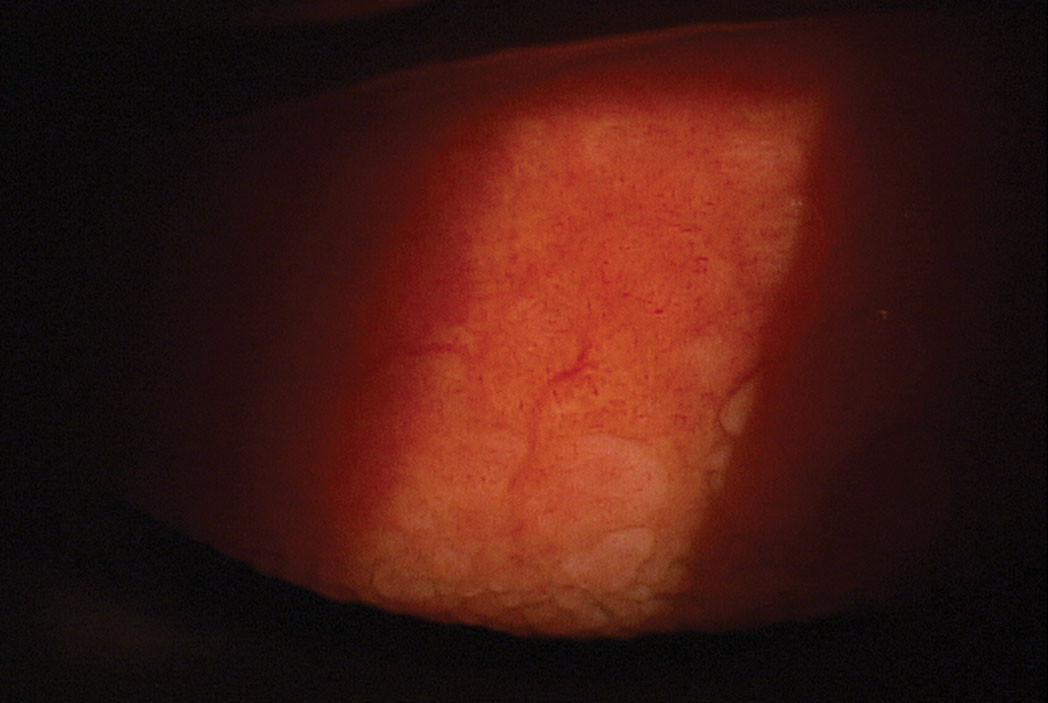

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis after treatment. Click image to enlarge. |

Disease Management

Acute VKC is often managed with topical antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers or steroids, but the larger concern—as previously mentioned—is recurrence, which can lead to severe complications that detract from quality of life as well as a child’s future potential.2 As such, effective long-term care is essential and must include educating patients and parents about the likelihood of recurrence and the need for prompt intervention.

Long-term therapy is best managed with calcineurin inhibitors, which include tacrolimus and cyclosporine. These are immune modulators that work to block IL-2 mediated Th2 lymphocyte proliferation, two critical components in the pathogenesis of VKC. Previously, doctors had the choice of using a commercial cyclosporine but at a much lower dose. More typical would be to compound these therapeutics.

Earlier this year a new drug called Verkazia was approved by the FDA for VKC. Verkazia is a higher concentration of cyclosporine (CsA) at 0.01% that comes in a unique oil-in-water, cationic emulsion. This second-generation oil emulsion is the same technology used in Retaine MGD drops that have been effective in MGD and evaporative dry eye disease management, and uses charged particles to increase bioavailability. The drug is dosed QID and indicated for children and adults with VKC. Recommended dosage is one drop four times a day, and can be discontinued after signs and symptoms are resolved. It can be reinitiated if there is a recurrence.

In Phase III clinical studies, the efficacy of high-dose CsA cationic emulsion in treating allergy symptoms, superficial punctate keratitis and overall quality of life scores was demonstrated in patients with severe cases. Verkazia improved keratitis, symptoms and quality of life scores in patients with severe VKC. There was also improvement in photophobia, tearing, itching and mucous discharge was greater with Verkazia QID and BID vs. vehicle over four months, although QID was the most effective. In the long-term, overall corneal fluorescein staining, visual analog symptoms and quality of life scores remained stable for up to 12 months with Verkazia. Adverse events were mild or moderate, with instillation site pain being most common. Verkazia was also well tolerated.1

Traditional therapies include topical mast cell stabilizers, topical antihistamines, dual-acting allergy drops, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, tacrolimus and lubricants.2 Supratarsal steroid injection or systemic therapy also may be indicated in some cases.2 Surgery may also be indicated to treat complications such as giant papillae, shield ulcers, keratoconus, LSCD or corneal opacity.2

As primary eye care providers, we must closely observe all patients with severe signs or symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis to rule out VKC. Focusing on the long-term care for VKC patients is of utmost importance, in addition to the acute, episodic intervention that relies on topical corticosteroids. Since this is a disease that primarily affects children, we must also consider developmental consequences, particularly in light of the fact that VKC can limit joyful activities such as school, sports and vacations, ultimately leading to psychological and relationship issues.1

Dr. Karpecki is medical director for Keplr Vision and the Dry Eye Institutes of Kentucky and Indiana. He is the Chief Clinical Editor for Review of Optometry and chairman of the affiliated New Technologies & Treatments conferences. A fixture in optometric clinical education, he provides consulting services to a wide array of ophthalmic clients. Dr. Karpecki’s full disclosure list can be found here.

| 1. Leonardi A, Doan S, Amrane M, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cyclosporine A cationic emulsion in pediatric vernal keratoconjunctivitis: The VEKTIS Study. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(5):671-81. 2. Singhal D, Sahay P, Maharana PK, Raj N, et al. Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64(3):289-311. 3. Kumar S. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a major review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87(2):133-47. 4. Ukponmwan CU. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis in Nigerians: 109 consecutive cases. Trop Doct. 2003;33(4):242-5. 5. Di Zazzo A, Bonini S, Fernandes M. Adult vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;20(5):501-6. 6. Leonardi A, Castegnaro A, Valerio ALG, Lazzarini D. Epidemiology of allergic conjunctivitis: clinical appearance and treatment patterns in a population-based study. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15(5):482-8. 7. Bonini S, Bonini S, Lambiase A, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis revisited: a case series of 195 patients with long-term followup. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(6):1157-63. 8. De Smedt S, Wildner G, Kestelyn P. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: an update. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(1):9-14. |