Trends and ControversiesCheck out the other feature articles in this month's issue: - Myopia: Should We Treat It Like a Disease? |

The story of optometry is that of a profession constantly evolving to meet the needs of the day. The refracting opticians who founded optometry more than a century ago would scarcely recognize it now—or, rather, would likely mistake it for ophthalmology. Though refractive services are still integral to optometry, medical eye care has occupied an ever-increasing share of our training and day-to-day practice.

But one notable difference between our profession and that of our MD colleagues is the approach to subspecialization. Ophthalmology has long recognized that many segments of the population need doctors to build expertise in a subset of the wider field of care by relinquishing other responsibilities. Surgical procedures essentially demand it. The ophthalmologists who perform trabeculectomies shouldn’t also do ILM peels, and vice-versa.

Optometry has a far less concrete approach to subspecialty practice. Anyone can call themselves a specialist of one kind or another—doing so is common among contact lens pros, for instance—but our institutions mostly leave validation of such claims to the honor system or a “proof is in the pudding” post hoc assessment of the outcome by patients. But that may be changing in the near future.

|

|

Clinicians with an expertise in binocular vision disorders may soon have a path for validation as subspecialists. Click image to enlarge. |

Reaching Higher

Generalists in optometry will always play a vital role, screening patients for a multitude of diseases—both ocular and systemic—and triaging their care while also serving the day-to-day refractive needs of the community. But for optometry to thrive, many practitioners must adapt to the many changes taking place in the field of medicine. Some say that one way ODs can reach higher is through a residency or by becoming an American Academy of Optometry (AAO) diplomate. However, these two programs traditionally do not have a mutually agreed upon, uniform set of standards. Some leaders in optometry have been looking to change that and are working to establish a shared, universal understanding of subspecialties in the field of optometry.

The profession itself is already considered a primary care specialty in the broader healthcare system, so when we refer to different areas of interest or expertise within optometry, we should use the term “subspecialty,” according to David Heath, OD, president of SUNY College of Optometry. Dr. Heath has served as president of the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO) twice. He’s also the co-chair of the Task Force on Subspecialization (TFSS), an initiative set up by ASCO and the AAO.

The TFSS was officially formed in 2018, although the AAO and ASCO joined forces with others to start its preliminary development in 2014 and 2015. At its outset in 2018, the TFSS set three goals:

- Establish a set of guidelines that define parameters for determining what is a subspecialty and a process by which the two organizations could formally recognize subspecialties in optometry.

- Facilitate the development and use of a designation called Advanced Competencies, which define the required knowledge and skills that represent a given subspecialty and what an optometrist should possess to be validated in that subspecialty.

- Establish more uniform nomenclature between what the ASCO uses as titles within residencies and what the AAO uses for credentialing diplomates in certain areas of fellowship.

According to Dr. Heath, while the TFSS has made progress toward those three goals, only the redesign of residency title guidelines has been fully realized, where increased development and use of Advanced Competencies is ongoing. He touts the significance of this milestone, noting that it will allow optometrists to know when an area actually qualifies for recognition as a subspecialty.

An interim report published by the TFSS in April 2020 states, “Through these three goals, ASCO and the AAO hope to establish the foundation and the conditions within which optometric subspecialties may evolve and be [accepted] in a considered and intentional manner against a recognized set of criteria and quality standards.” The TFSS is working on its final report.

|

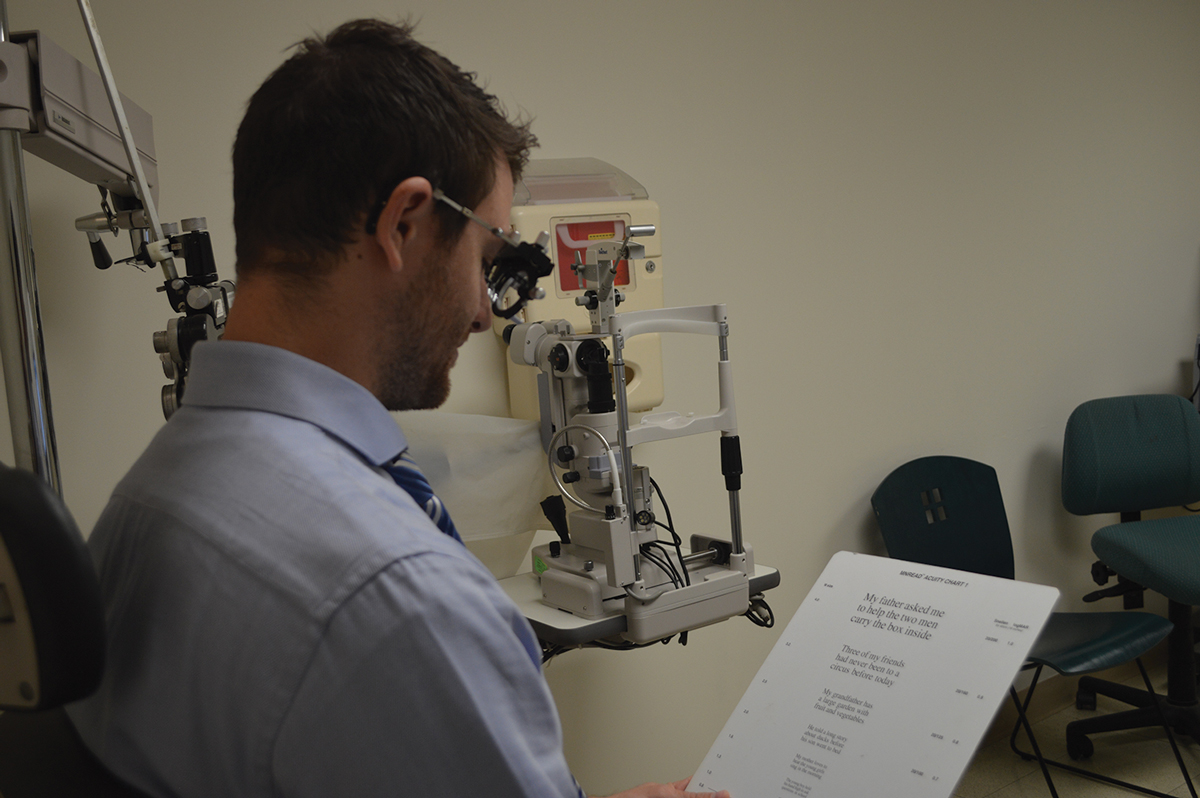

| Experts speculate that low vision will be the first subspecialty formally recognized in optometry. Photo by Alexis Malkin, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Why Make It Official?

The move toward subspecialization in optometry is nothing new, Dr. Heath says, noting that exploration of the need “has arisen on a regular basis since the late 1960s.”

While high-level thinking on the prospect of subspecialization has flourished—in the form of committees, commissions, publications, presentations and recommendations—not much has trickled down to the level of clinical practice just yet. “In spite of past initiatives to proactively manage the development of post-graduate specialization within the profession, these efforts have failed,” says Dr. Heath.

Instead, what has transpired is the creation of special interest groups, sections and committees among various institutions. However, Dr. Health points out that “the nomenclature for areas of interest used by these groups is varied, and few have clearly defined criteria.”

The defining of specialties and the evolution of subspecialties seems to occur in nearly all areas of medicine. While the American Board of Medical Subspecialties (ABMS) recognizes general ophthalmology as a specialty in medicine, it does not recognize any subspecialties in ophthalmology. However, subspecialties in ophthalmology are recognized by the Association of University Professors in Ophthalmology, and they have a well-developed program with requirements linked to fellowship education, laying the groundwork for perhaps someday making subspecialties in ophthalmology accepted by the ABMS as well.

The TFSS April 2020 report states, “The example of ophthalmology’s subspecialties is effectively a credential-based system that stands in contrast to the board certification-based process of ABMS. It is possible that at some point in time, those subspecialties could move toward developing the appropriate structure and [board certification] process to apply for ABMS recognition.”

However, the question on many optometrists’ minds once they hear about the push for subspecialty recognition and validation in optometry remains, “Do we really need this?”

Academy Sections and SIGs Help ODs Delve DeepFuture optometry students will have the option to pursue formalized subspecialties as part of their educational curricula. But less formal ways to develop a niche area of expertise are already available to existing practitioners, most notably through the Sections and Special Interest Groups (SIGs) within the American Academy of Optometry (AAO). The Academy has eight Sections that each act as a vehicle for optometrists with interest in subspecialty areas to meet around particular topics, according to the AAO:

SIGs, by contrast, are for members who have a special interest in areas that are too narrow to warrant a complete diplomate program. These groups provide a forum for clinicians interested in academic medical centers, research, neuro-ophthalmic disorders, nutrition, disease prevention, wellness, retina, vision in aging and vision science. Sections and SIGs produce symposia for the Academy’s annual meeting and serve as the Academy’s resource in these particular topics. “The American Academy of Optometry’s Sections and SIGs give our members a home within the Academy where they can connect, share knowledge and collaborate on a particular topic that interests them,” says President Barbara Caffery, OD, PhD. Members make use of these tailored resources and networking opportunities with like-minded ODs to advance their skills and capabilities. In so doing, they start on the path to a subspecialization, or at least concentration, in the areas of care they’re most passionate about. |

Kristin Protosow, OD, part-owner of Eye Vision Associates, a multispecialty practice in Nesconset, NY, and past president of her county’s optometric society for five years, says she’s not sure. Her practice employs optometrists who focus on low vision, specialty contact lens fitting, myopia control and dry eye, as well as serving those who need primary care and ocular disease management. All five of the doctors who work there have completed residencies and are AAO fellows. When she asked them if they would consider going for subspecialty validation, should it someday be an option, she said her colleagues were torn.

“I think that we would do it if we had to, but not advocate for it,” says Dr. Protosow. “We feel like it would go unnoticed by patients, and we are already known for our specialties, so I’m not sure what the point would be.”

The motivation could be stronger for new doctors pursuing residency. “It might be easy because it will already set up for them to be validated with a subspecialty upon completion of their residency,” Dr. Protosow suggests.

Dr. Protosow is right in that the stage is being set to make it easy for residents to also become validated in certain subspecialties in the future, now that the TFSS has succeeded in achieving one of its goals: increasing the use of common nomenclature and the development of commonly understood advanced competencies.

|

|

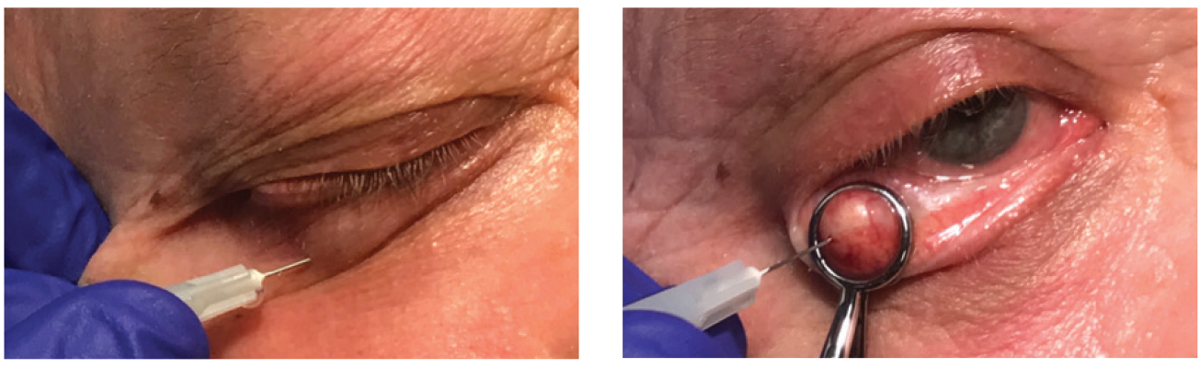

The dearth of MDs may push ODs to pursue subspecialty training in some lid and laser procedures, according to Dr. Damari. Photos by Jackie Burress, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Would it be beneficial for optometrists who are already well established in their career and their area of specialty, like Joseph Shovlin, OD, to go for subspecialty validation? Anyone can see that he has the credentials of an expert in the area of cornea and specialty contact lenses—he’s an AAO diplomate in the Cornea, Contact Lenses and Refractive Technologies Section. He also chaired the American Optometric Association’s (AOA) Cornea and Contact Lens Section, was a consultant and voting member of the FDA’s Ophthalmic Devices panel and has lectured on related topics for more than 30 years. He was even there when soft contact lenses first started being produced in the United States. “I had the pleasure of working very early in my career with Bob Morrison in Harrisburg, PA. He held the patents along with his attorneys for the first soft lens from the Czech Academy of Science under Otto Wichterle,” Dr. Shovlin notes.

Dr. Shovlin says he definitely would go for subspecialty validation himself when it becomes available, but his advice to others is simple. “Regardless of attaining specialization status someday or not, it goes without saying that doing the very best you can do for each and every patient is paramount to success.” He defines success as “personal satisfaction in what we do daily in helping others and being rewarded fairly” for it.

He also adds, “Keep in mind, nothing really beats ‘word of mouth’ recommendations from satisfied patients.”

Although only some optometrists may see the advantages of optometry obtaining subspecialty validation, Dr. Heath says there are not only advantages for the individual OD but also for the public as well. Dr. Heath reasons that subspecialization will help encourage more intra-optometry referrals. It may be one way for other ODs to identify true experts in certain areas and allow us to place patients who have needs we think we cannot handle into the trusted hands of another optometrist, he says.

Also, Dr. Heath says, it would help the public better understand who could best address their specific problems. Optometrists with subspecialty training will have demonstrated competency, and those skills will be more consistent between those who consider themselves subspecialists. He says that when one OD does a residency in one program, they may not have had the same experiences or exposures as another OD doing the same type of residency in a different program, so we cannot be sure their knowledge base and level of expertise is equivalent.

The development of common Advanced Competencies for subspecialties will be one step toward ensuring that each subspecialist has been subjected to a similar post-graduate experience and has demonstrated a mastery of common knowledge and skills.

The AOA on Securing Optometry’s FutureAlthough not part of the subspecialization task force spearheaded by the AAO and ASCO, the AOA also advocates for the evolution of the profession, particularly in scope of practice expansion. When asked about the current state of optometry and its future, AOA President William T. Reynolds, OD, provided the following summary of the AOA’s position and priorities: “Just as technology has progressed, health care has been rapidly evolving during the past several decades. Knowing that optometry needs to adapt and anticipate the future, the AOA, along with the dedicated Board of Trustees and volunteers, has focused on key long-term strategies to help pave the way for the future and position doctors of optometry as frontline providers of essential care. To accomplish this, we’ve made ensuring full recognition of our physician role and advancing our scope of practice immediate priorities. As a profession, optometry delivers 85% of the primary eye health care in America, with doctors of optometry practicing in counties that make up 99% of the US population. And when routine care was halted during the pandemic, about 80% of doctors of optometry, surveyed by AOA’s Health Policy Institute, indicated they provided urgent/emergent care, reducing the burden on hospital emergency departments. And 25% of the medical care AOA members delivered during COVID was surgical. Building on this accessibility, a report by Avalon Health Economics detailed that Americans would save at least $4.6 billion annually if states modernized their optometric scope of practice acts to a level commensurate with optometry’s advanced education and training. That level of accessibility and economic savings is why the AOA and state affiliates contend that optometry is well-positioned, highly educated and qualified to provide the breadth of expanded eye health and vision care services that doctors have delivered for years in progressive states, including Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kentucky and Alaska. However, restrictive state laws based on outdated and tired misrepresentations of optometry’s education and capabilities have created barriers to maintain a status quo. AOA and affiliates are working tirelessly across the country to modernize state scope of practice statutes to allow doctors of optometry to practice to the top of their license and utilize their full skillset, including fully recognizing new and advanced procedures that reflect contemporary optometry practice.” |

David A. Damari, OD, is the dean of Michigan College of Optometry and, like Dr. Heath, is all for subspecialization in optometry. Dr. Damari is not only a member on the TFSS but also past president of the College of Optometrists in Vision Development, an organization that administers an extensive credentialing process to certify advanced competence in the care of binocular vision, accommodative, eye movement and visual perceptual disorders.

Dr. Damari agrees with Dr. Heath that subspecialization may lead to more OD-to-OD referrals. “Our profession needs to better serve patients who have non-surgical vision and ocular health needs that go beyond the scope of what we can teach in a four-year program.” In fact, as access to some eye surgeries becomes constrained by overwhelming pressure on ophthalmologists’ schedules, “I could easily see some optometrists earning subspecialty certification in some lid or laser procedures.”

He recounts an anecdote about Anthony Adams, OD, PhD, former dean of UC Berkeley School of Optometry. “Dr. Adams once said to me that our profession wasn’t truly mature until we began referring to each other for these types of specialty services,” says Dr. Damari. “I firmly believe that one of the reasons many optometrists do not recognize the benefits of vision therapy for strabismus, or even non-strabismic disorders, is that they are not confident that if they refer that patient to another OD, the patient will be receiving truly effective, advanced care. A certification process would help provide that assurance.”

Subspecialization will help to get the public the best care possible, says Dr. Damari. When patients have conditions such as strabismus and other binocular vision disorders, “it truly has a significant impact on their quality of life, and can even change the course of their career or academic progress. For them not to receive services to manage those disorders has a negative impact on their future earning ability, on the economy and their employer.”

If referred by their primary optometrist, says Dr. Damari, “that OD would look like a hero for detecting the condition and recognizing that it needed to be treated. And the patient would know that their primary OD was referring them to a subspecialist in that one specific area who knows how to get the best outcome for the patient, and then the patient can return to the primary optometrist for their other vision care needs.” Additionally, “as technology develops and our entire US economy moves even farther away from working with the hands to working with our vision, we need, more than ever, to service people’s complex visual conditions and needs, such as myopia, visual efficiency disorders and visual spatial perception disorders. We are the only profession that is well-trained to provide these services.”

|

|

Vision therapy is another subspecialty that could benefit significantly from a formalized certification process. Optometrists could refer patients with more confidence, Dr. Damari speculates. Photo by Marc B. Taub, OD, MS, and Paul Harris, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The Road Ahead

Dr. Heath says that for optometrists entering the residency program beginning July 2021, “new residency title guidelines will be used, and these do anticipate the development of subspecialties in optometry.” He does say, however, that it will take a number of years for more formal development of subspecialties to happen, and he predicts low vision will be the first official subspecialty to be formally recognized, given its set of well-developed Advanced Competencies.

The contentious question, as always, surrounds the issue of validation. Who sets the criteria and performs the assessments? There are many stakeholders in optometry who could lay claim to that role. Some optometrists will also likely worry that the entire enterprise could come off as Board Certification 2.0—another bitter internecine fight. Proponents of subspecialization will need to roll out the discourse in a way that encourages participation without alienating those who choose to refrain.

Even though the Task Force hasn’t fully accomplished all three of its goals, it hopes the work already done provides the foundation for and momentum toward a more formal structure that will facilitate the emergence of subspecialties in optometry. Ultimately, it would like other associations and organizations within optometry to get involved and unite toward the same goal of defining subspecialties and developing validation. Dr. Heath says he would like to see a national summit on optometric subspecialties take place, but notes such a summit is unlikely until after the COVID-19 pandemic recedes.

Dr. Murphy practices at Sachem Eye Care in Lake Ronkonkoma, NY, where she provides comprehensive eye exams and contact lens fittings of all types.