|

History

A 24-year-old African American female presented with a chief complaint of cloudy vision in both eyes, worsening over the past week. She also complained that portions of her side vision in both eyes were missing and that she noticed balance problems. She denied diplopia, pulsatile tinnitus, vomiting, nausea or lower back pain.

Her systemic history was positive for hypertension for the past five years, as well as asthma and obesity. Her medications included Advair (fluticasone/salmeterol, GlaxoSmithKline), Benicar (olmesartan, Daiichi Sankyo), Aleve (naproxen, Bayer Healthcare) and albuterol. She reported having had a lumbar puncture one year prior for an “infection,” but no treatment was initiated.

She reported no allergies, and her ocular history was unremarkable.

|

|

|

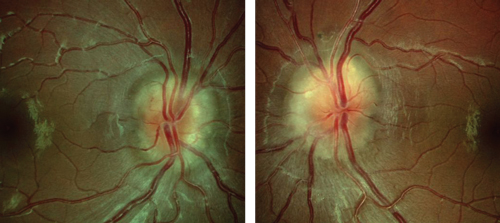

| Fundus images of a 24-year-old female patient presenting with cloudy vision in OD (left) and OS (right). |

Diagnostic Data

Her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/25 OU. Pupils were normal with no afferent defect. Her extraocular muscle movements were full and smooth in both eyes. Confrontation visual fields were restricted 360° OU.

Biomicrosopy revealed normal external ocular structures in both eyes. Intraocular pressure measured 14mm Hg OU. Blood pressure was 173/92mm Hg, right arm sitting.

The photographs illustrate the dilated fundus examination.

Your Diagnosis

How would you approach this case? Does this patient require any additional tests? What is your diagnosis? How would you manage this patient? What’s the likely prognosis?

Thanks to Heather R. Miller, OD, of Southampton, Pa., for contributing this case.

Discussion

Additional testing to assess the macula and optic nerve function included red desaturation, brightness desaturation, as well as color vision evaluation; all interpreted as normal.

An automated visual field was performed to assess the visual pathway and quantify the results of confrontational testing. Following the dilated fundus exam, we ordered several laboratory tests: blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, complete blood count with differential, platelet count, lyme titer, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), reactive plasma regain (RPR), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE).

In addition, neuroimaging was ordered, which included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance venugraphy (MRV). Neuroimaging results came back normal, and lumbar puncture was suggested.

The diagnosis in the case was idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri (PTC).

IIH is a diagnosis of exclusion. Today, the Modified Dandy’s Criteria are used to certify suspected cases:1,2

1. Signs and symptoms of intracranial hypertension in an alert and oriented patient with no localizing neurologic findings (abducens deficit excepted)

2. All neuro-imaging normal

3. Normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition

4. Opening CSF pressure of >200mm of H2

O in non-obese patients or >250mm H2

O in obese patients in the absence of another explanation.

IIH has a strong association with obesity or recent weight gain, although the exact pathogenesis is still unknown.1-3 Corticosteroid withdrawal, Addison’s disease, hypervitaminosis A, thyroid therapy, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, defective CSF absorption, Behçet’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus have all been associated with IIH.1-3 Medications such as birth control pills, isotretinoin, lithium, tetracyclines or anabolic steroids have also been linked with IIH.1-3

The mainstay of treatment is weight management with azetazolamide prescribed to decrease the volume of cerebrospinal fluid.1-4 Severe cases warrant shunts or optic nerve sheath fenestration.4

Patients with optic disc edema should have immediate visual fields, photos, neuro-ophtalmic examination and an MRI to rule out space-occupying lesions. They should be sent for lumbar puncture to determine the opening pressure and CSF composition; other causes for increased intracranial pressure should be eliminated. Closely monitor patients with IIH to decrease the risk of deterioration of vision.

In this patient’s case, we referred her to the neuro-ophthalmology service where imaging and lumbar puncture confirmed the diagnosis. All other systemic testing was negative. The patient was placed on a low-fat diet with the goal of significant weight loss and monitored for resolution. The use of oral medications such as diuretics like acetazolamide was under consideration but not promptly started.

1. Bruce B, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Update on Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011 Aug;152(2):163-9.2. Malloy K. Department of Neuro-ophthalmology, Salus University, Philadelphia, 2014: Personal communication.

3. Kline LB. Neuro-Ophthalmology; Review Manual. 6th ed. Slack Inc., New Jersey. 2008;139-142.

4. Nithyanandam S, Manayath G, Battu R. Optic nerve sheath decompression for visual loss in intracranial hypertension: Report from a tertiary care center in South India. Indian J Ophthalmol.. 2008 Mar-Apr;56(2):115-20.

5. Sugerman H, Felton W, Sismanis A, et al. Gastric surgery for pseudotumor cerebri associated with severe obesity. Ann Surg. 1999 May;229(5):634-40.

6. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin. 2010 Aug;28(3);593-617.