|

A 58-year-old female self-referred to another provider, but eventually made it back to my office—with more issues than she left with.

Diagnostic Data

In late 2017, a new patient presented for a comprehensive evaluation secondary to blurred vision OS>OD. She reported that her vision had been blurrier OU over the past 12 months. Medications included an antibiotic, a nasal spray and an oral steroid, as she was dealing with chronic sinusitis. She had an allergy to sulfa drugs.

Her entering uncorrected distance visual acuities were 20/25- OD and 20/50- OS. Pupils were ERRLA with no afferent pupillary defect. EOMs were full in all positions of gaze. She wore OTC readers. Best-corrected acuities through minimally hyperopic and astigmatic correction were 20/20 OD and 20/40-OS.

A slit lamp examination of the patient’s anterior segments was unremarkable OU. Applanation tensions were 19mm Hg OD and OS. The anterior chamber angles were wide open, and her anterior chambers were quiet. Upon dilation, her crystalline lenses were clear OU. The vitreous cavity OD was essentially unremarkable, whereas the left showed a partial PVD. She denied flashes and floaters.

|

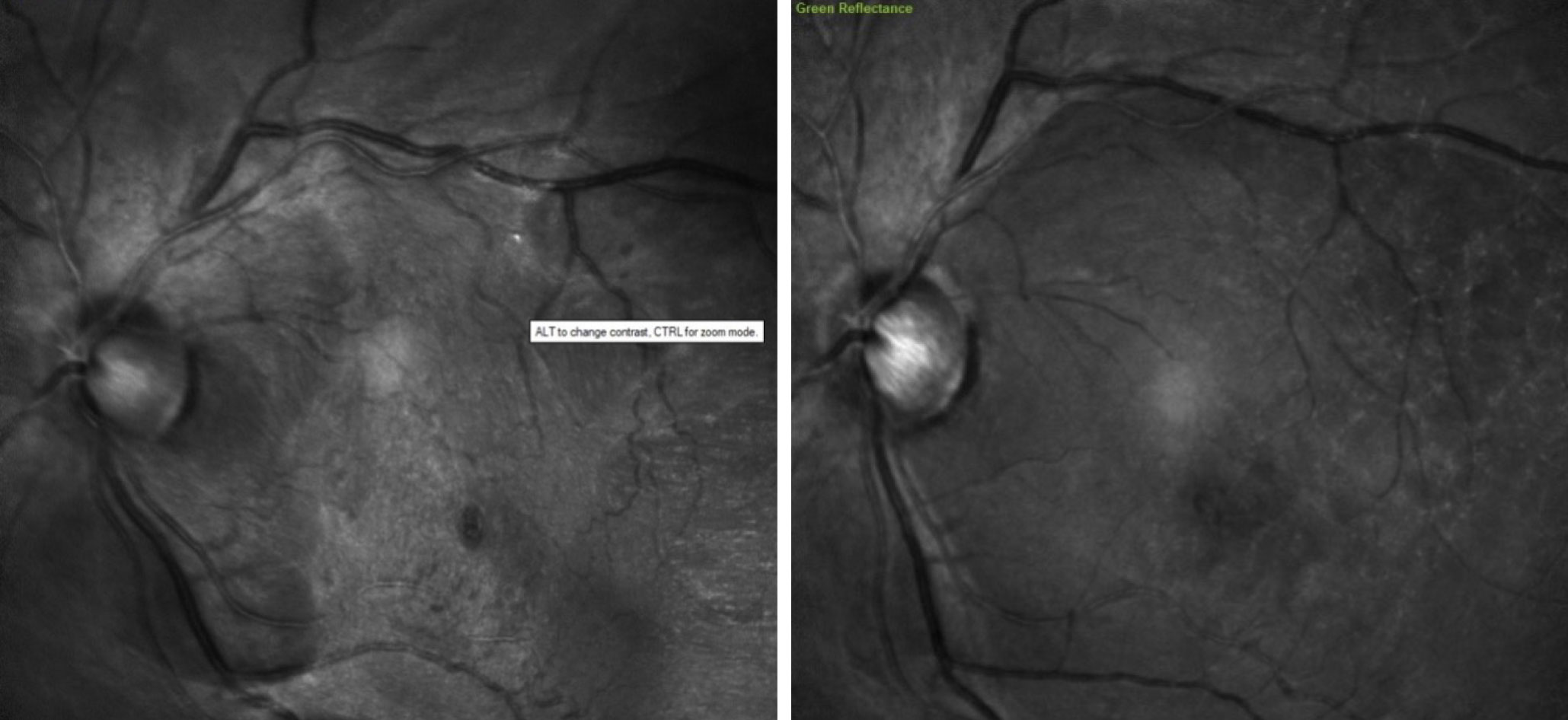

| Note the initial central macular and foveal distortion (left). Here we see significant reduction in distortion post-vitrectomy (right). Click image to enlarge. |

Through dilated pupils, her posterior pole was remarkable for slightly large discs OU with concurrent large cups OS>OD. Cup-to-disc ratios were 0.55 x 0.6 OD and 0.55 x 0.7 OS. The right macula was clear; the left was characterized by a distinct ERM with what appeared to be a macular pseudohole. There were no concurrent macular diseases present. The retinal vasculature was healthy, with no abnormalities noted. Her peripheral retinal evaluation was unremarkable OU except for the partial PVD with remaining peripheral retinal vitreomacular adhesion (VMA).

Based on these findings, fundus photos and posterior pole OCT images were obtained at the initial visit. Macular OCT confirmed ERM along with pseudohole secondary to mild VMA. The patient was asked to return in six to eight weeks for a dilated exam to follow-up on the partial PVD and subsequent VMA, as well as the presence of suspicious discs.

The patient followed up as asked, and optic nerve and macular OCTs were obtained. The OCT of the left eye was unchanged from the baseline scan. The optic nerve OCT demonstrated slightly larger discs and a slightly thinned though statistically normal neuroretinal rim OS on BMO-MRW radial scans. Her circumpapillary RNFL scans were normal. Applanation tensions at this visit were 21mm Hg OD and 20mm Hg OS. She was asked to follow-up in six months to reassess the maculae and the optic nerves.

She presented at this visit with complaints of “somewhat blurrier” vision OS. Visual acuities OD were unchanged, whereas those of the left eye had decreased to 20/50, with no pinhole improvement. Applanation tensions were 20mm Hg OD and 21mm Hg OS. On dilated fundus examination, it was clear that the VMA had released, leaving behind a slightly increased presence of an ERM. This was confirmed on OCT imaging. Her optic nerves were stable on OCT, both from a perioptic RNFL and BMO radial scan perspective.

|

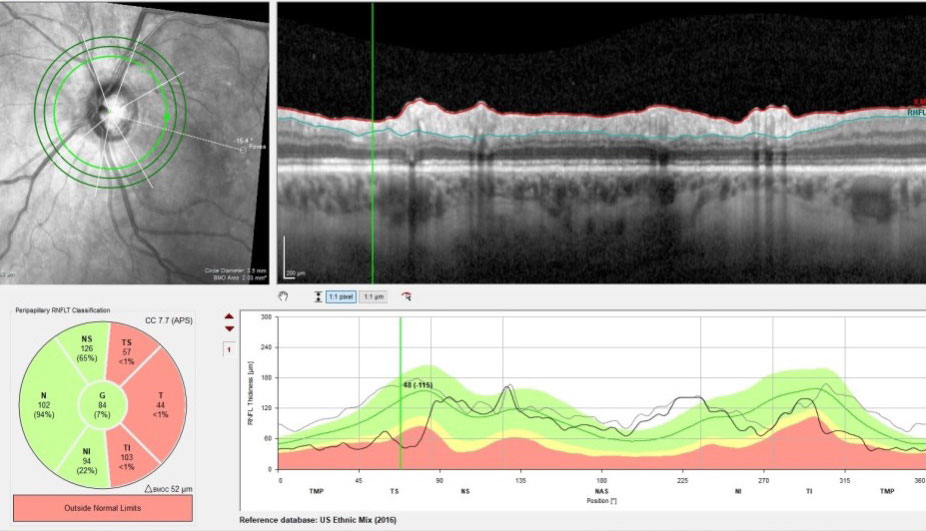

| Follow-up RNFL circle OCT scans OS compared with baseline. Note in the area marked on the TSNIT graph a 115μm decrease in thickness from baseline. In conjunction with the last image, it is clear that this is glaucomatous change. Click image to enlarge. |

We discussed her options for improving vision in the left eye vs. passive monitoring. She indicated she would prefer to see how things progressed over the next six months. When she returned at that time, her acuities and OCTs were stable, as were her complaints of decreased vision OS and she seemed content. At this point, we were in mid-2019, and she was asked to return in six months.

Compliance with patient care can always be an issue, whether it is related to glaucoma medication schedules or follow-ups. This patient, though initially compliant with scheduled visits, ultimately chose to see a retinologist related to her decreased vision OS.

She presented back to me in late spring of 2021 with complaints of worsening vision in the left eye. She reported that the retinologist did a “procedure” on her left eye in early 2020 that resulted in some improvement in vision OS, but she said it seemed to be worsening. The retinologist discharged her and told her he had done all he could for her vision at that point. She last saw him in early 2021.

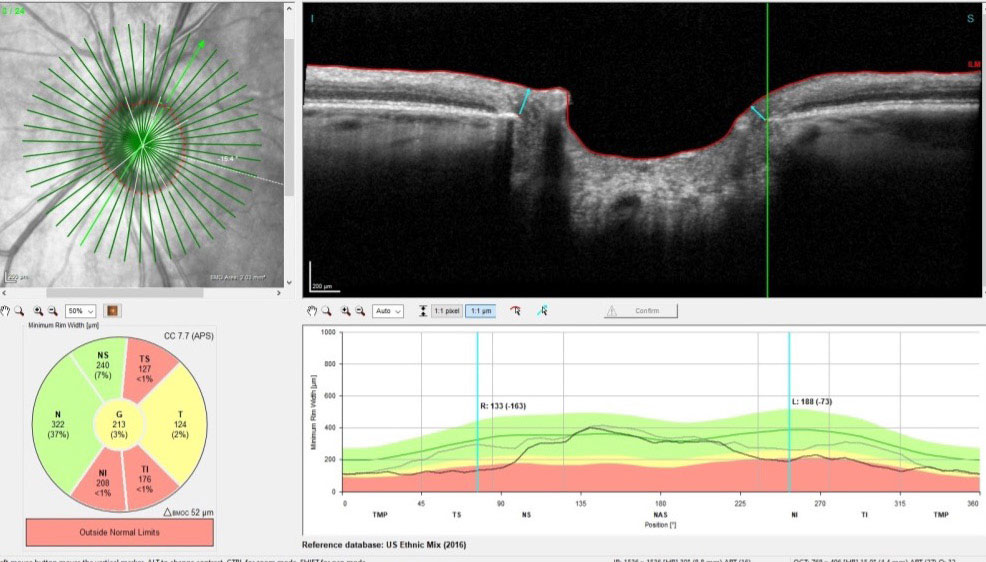

At her first visit back with me, the right eye was unchanged. The left eye, however, had reduced visual acuity to 20/80-, best-corrected to 20/50- through a moderately myopic correction. Upon slit lamp examination, she had 2+ nuclear sclerosis OS; the crystalline lens of the right eye was clear. On dilated fundus examination, she had a vitrectomy and membrane peel OS, and the macular appearance had improved compared with pre-retinal surgery. However, there was a significant change in both her RNFL circle scans as well as the BMO radial optic nerve scans. Essentially, there was significant thinning to the RNFL and the neuroretinal rim OS. There were no optic nerve changes seen in vivo or on OCT imaging of the right eye.

Clearly, the reduced visual acuity OS was primarily due to the cataract, which is common post-vitrectomy. However, of more concern was the significant thinning of the RNFL and the neuroretinal rim OS on OCT.

|

| Radial scans of the neuroretinal rim, measuring the BMO-MRW. Note that this is a follow-up scan compared with baseline, and in the superotemporal sector indicated, there is a 163μm decrease in neuroretinal rim width. This is not related to VMA release. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

This case makes two major points, the latter being the most important.

Point 1. Typically, as glaucoma progresses we will observe thinning in three areas of the posterior segment OCT scans: the macular ganglion cell layer, circumpapillary RNFL and BMO radial scans of the neuroretinal rim. That said, concurrent macular disease can interfere with our interpretation of the ganglion cell layer and the circumpapillary RNFL. In these cases, where there is an ERM with or without VMA or vitreomacular traction (VMT), the RNFL in particular can be distorted and measures of RNFL thickness can be artificially elevated. Furthermore, following membrane peels or release of VMT or VMA, those once-thicker RNFL readings may subsequently measure thinner. This doesn’t necessarily indicate glaucomatous progression on OCT; you may be looking at changes in the RNFL (and ganglion cell layer to a lesser degree) due to the concurrent macular disease. Remain cautious of what your OCT is telling you, and also what it’s not telling you.

In this case, however, while there is significant RNFL thinning, the large majority is occurring in the inferotemporal and superotemporal sectors, both of which are where glaucomatous damage is seen. Furthermore, there is progressive thinning of the neuroretinal rim, which is not affected by the patient’s VMA or ERM. OCT makes it clear the patient has developed significant glaucomatous changes OS since last seen pre-vitrectomy.

Point 2. Unfortunately, all too often my fellow OD colleagues mention they are not going to give a patient who is seeing a retinologist a complete exam. They assume the other ophthalmic provider is a “specialist” and therefore has all of the aspects of care under control. That can be a slippery slope. This is a good example of that scenario. The retinologist did what retinologists do: a vitrectomy and a membrane peel. But he didn’t deal with the cataract that was forming (our job) or the glaucoma that developed following surgery (definitely our job).

We are the specialists in eye care. We are charged with managing the global eye health of our patients correctly. You are responsible for the patient in your chair, even for conditions they may already be undergoing treatment for with another provider.

Dr. Fanelli is in private practice in North Carolina and is the founder and director of the Cape Fear Eye Institute in Wilmington, NC. He is chairman of the EyeSki Optometric Conference and the CE in Italy/Europe Conference. He is an adjunct faculty member of PCO, Western U and UAB School of Optometry. He is on advisory boards for Heidelberg Engineering and Glaukos.