|

History

A 57-year-old black female reported to the office with a chief complaint of dimmed vision in her left eye for a week. She noticed the change in vision after a procedure to treat her glaucoma. A phone call to that practice revealed that the patient had a drainage valve implanted in her left eye to augment a failing trabeculectomy.

She was placed on topical antibiotics, topical steroids and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications QID and removed from all topical glaucoma medications.

Her systemic history was remarkable for hypertension, for which she was properly medicated. She denied allergies of any kind.

|

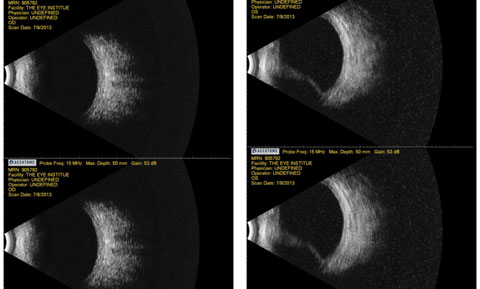

| Fig. 1. Above, this B-scan ultrasonography shows test results from a patient who complained of diminished vision for a week. She had recently had a drainage valve implanted to help with her glaucoma. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnostic Data

Her best corrected entering visual acuities were 20/30 OD and 20/20 OS at distance and near with no improvement upon pinhole. Her external examination was normal with no evidence of afferent pupil defect. The biomicroscopic examination of the anterior segment was normal with a well placed drainage device and no evidence of complications. Goldmann applanation tonometry measured 15mm Hg in both eyes. Studies included stereo-biomicroscopic examination of the fundus, photodocumentation and B-scan ultrasonography (Figure 1).

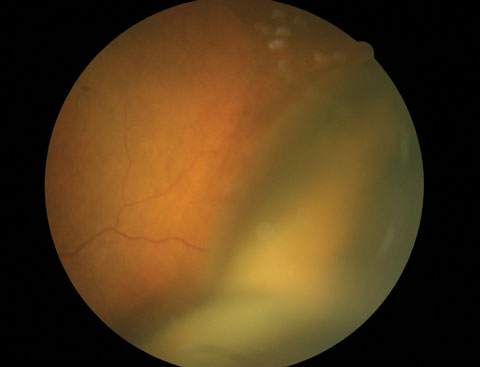

Pertinent clinical findings in the posterior segment of the left eye are demonstrated (Figure 2).

Your Diagnosis

Does this case require additional tests? How would you manage this patient? What is the likely prognosis?

|

| Fig. 2. At left, this fundus photo shows the pertinent clinical findings. Can you identify it? |

Discussion

Additional studies included stereobiomicroscopic examination of the fundus, photodocumentation and B-scan ultrasonography.

The diagnosis in this issue is choroidal detachment secondary to hypotony as a complication of seton placement, OS. The terms uveal effusion, choroidal effusion, ciliochoroidal effusion, ciliochoroidal detachment and choroidal detachment have all been used interchangeably in the literature.1-15 The condition connotes an abnormal collection of fluid that has expanded inside the suprachoroidal space (the potential space between the sclera and choroidal tissue), producing internal elevation and separation of the choroid from the sclera.1-5 Various inflammatory and hydrostatic conditions can cause uveal effusion.1-7 The condition can also occur as a result of trauma or spontaneously with no obvious cause. Spontaneous choroidal detachment is known as uveal effusion syndrome (UES).1,2

The choroid is a thin vascular component of anatomic structure known as the uvea (choroid, ciliary body, iris).6,7 It is a multi-layered structure (Haller vascular layer, Sattler capillary layer, Bruch’s membrane interface) sandwiched between the sclera and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).6,7 While natural attachments to the RPE are firm and vortex vasculature tethering supplies external support, a potential separation exists between the choroid and sclera known as the perichoroidal or suprachoroidal space.6 The space houses pigmented sheets of connective tissue (suprachoroidal lamina), long and short posterior ciliary vessels and nerves.6,7 Any interruption, pathophysiological or traumatic that introduces fluid or blood between the structures or drop in eye pressure (hypotony) that decreases intraocular support can create an environment permitting the choroid to separate from the sclera.1-15

Serous and hemorrhagic choroidal detachments are characterized by fluidic separation of the retina/choroid following leakage of fluid or blood into suprachoroidal space.1-7 The accumulation of fluid or blood is typically induced by complications of various intraocular surgeries (cataract, glaucoma and retinal detachment surgery), where hypotony is combined with postoperative inflammation and or hemorrhage from a damaged choroidal vessel.2-5 Other nonsurgical conditions associated with uveal effusion include idiopathic microphthalmia and inflammatory diseases such as scleritis, sympathic ophthalmia, pars planitis, Harada’s disease.2,9-16

Choroidal detachment of any sort creates a variable anular, lobular, firm bullous protrusion of the choroid/retina into the posterior segment. The appearance (anular, lobulated, multilobulated) is variable depending upon the location of the detachment (anterior to the equator, anular) vs. postquatorial, lobulated vs. multilobulated).5 In most instances, serous choroidal detachments are painless, however, hemorrhagic choroidal detachments are frequently painful.5 Choroidal detachments induce visual changes and can push the iris diaphragm forward, shallowing the anterior chamber.5

The pathophysiology of idiopathic serous detachment of the choroid is hypothesized to be caused by scleral abnormalities associated with naturally occurring hypoplasia or partial absence of the vortex venous system.1 Patients with UES are most typically middle-aged men who have a relapsing remitting clinical course. There is often coexisting, shifting subretinal fluid that may involve the macula. Chronic disease may lead to secondary retinal pigment epithelial (leopard spots) changes and permanently reduced visual acuity.

Histological studies show amorphous glycosaminoglycan-like material filling the interfibrillary spaces of excised scleral tissue with disruption of collagen fibers. In some patients there may be reduced macromolecular diffusion that interferes with the normal transscleral egress of albumin out of the eye, perhaps causing choroidal fluid retention due to altered osmotic forces. An alternative and perhaps complementary hypothesis, is that swollen sclera compresses the transscleral vessels with resulting fluid retention. UES is always a diagnosis of exclusion.

Most cases of postoperative choroidal detachment resolve spontaneously.2 Resolution is usually associated with rapid normalization of the intraocular pressure and reduction of intraocular inflammation.2 The natural course of the idiopathic condition is variable but tends to be prolonged with remissions and exacerbations.1,2

Treatment with systemic steroids does not appear to be effective. Surgical decompression of the vortex veins as they pass through the sclera has been described, but the most common treatment is a full-thickness sclerectomy to provide an exit for choroidal fluid. The largest case series suggests that this produces an anatomic improvement in approximately 83% of treated eyes after a single procedure and in about 96% after one or two procedures. In most instance visual acuity improves by two or more lines in 56% of the eyes. Acuity remains stable in 35% of eyes and worsens in 9%. Surgical management involving vortex vein decompression is also effective.1,2 Although extremely rare, UES is a serious condition that is difficult to treat and can lead to severe and permanent visual loss in both eyes.1

|