|

An 80-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic with complaints of blurred vision on his right side of one month’s duration. This was especially noticeable when the patient attempted to read. In addition, he reported mild right-sided weakness for the past five weeks. The patient’s medical history was positive for long-standing hypertension and Type 2 diabetes.

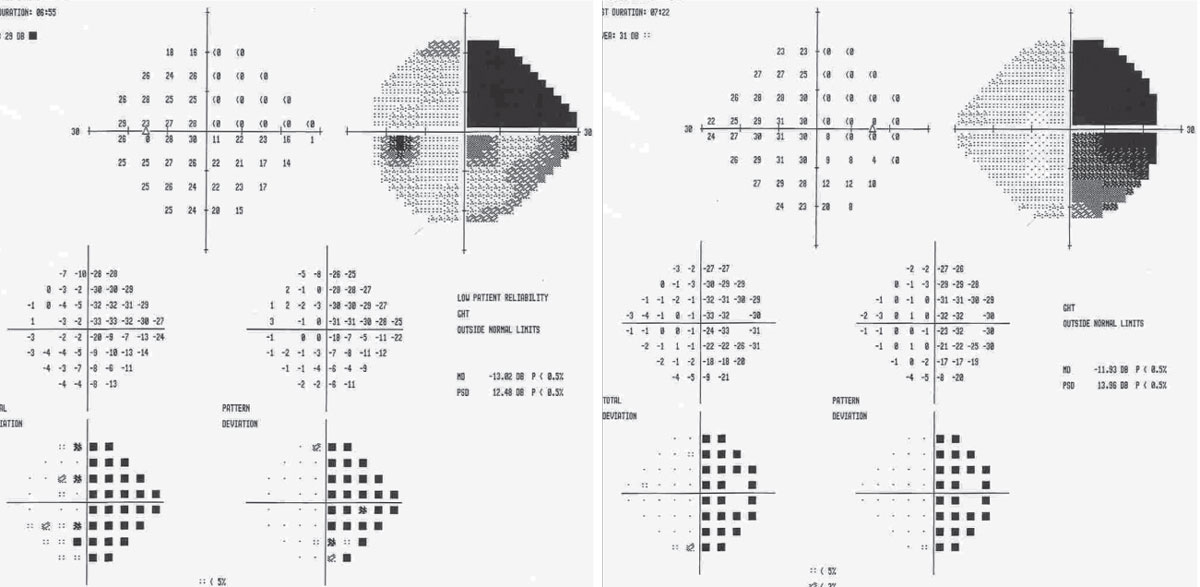

His visual acuities were 20/20 OD, OS. He had a grade 1+ relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) in the right eye, and confrontation fields revealed a right field deficit in each eye. Threshold perimetry revealed a right homonymous hemianopia (Figure 1).

An Unfortunate Turn of Events

These concerning signs and symptoms prompted emergent neuroimaging, which revealed a left optic tract mass consistent with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). The tumor was compressing the left optic tract and the crus cerebri (cerebral peduncle) of the midbrain, thus creating the right RAPD and right-sided weakness. He was referred for neurosurgical evaluation and treatment.

Gliomas represent the most common form of brain tumor. They originate in the glial cells that support the brain’s neurons, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and ependymal cells. GBM is the most malignant form of glioma, causing 3% to 4% of all cancer-related deaths.1 The World Health Organization defines GBM as a grade IV cancer characterized as malignant, mitotically active and predisposed to necrosis.1,2

Optometrists are in a position to detect early signs of GBM and perhaps help improve the paltry average survival of 12 to 15 months.1

|

| Fig. 1. Visual field defects may indicate signs of tumor progression in GBM and should prompt further investigation. Click image to enlarge. |

Hard Facts

GBM is a type of malignant brain tumor that forms from the star-shaped glial cells known as astrocytes. According to the American Brain Tumor Association, about 80,000 new cases of primary brain tumors are expected to be diagnosed annually in the United States. Of these, GBM will account for around 15%.3 GBM rarely metastasizes to other parts of the body.

While GBM is not the most common brain tumor, it is the deadliest; median survival is just 14.6 months after diagnosis if a patient undergoes standard therapy of tumor resection with concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. As such, a desperate need exists to identify new therapies to prevent and treat GBM. The development of proteomic, genetic and epigenetic tools may one day improve survival rates.3

Symptoms of GBM may appear slowly and be quite subtle, at first. Patients with GBM may present with headaches, confusion, memory loss, motor weakness and seizures. Other patient complaints include nausea, personality changes, difficulty concentrating, hemiparesis, vision loss and aphasia.4

Neoplastic DiseaseCancer is responsible for approximately 25% of all deaths in the United States and is the second most common cause of death after heart disease. The American Cancer Society defines cancer (or carcinoma) as a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells. Cancer has the capacity to invade surrounding normal tissue, metastasize and kill the host in which it originates.2 Cancer has environmental, chemical, cellular and genetic causes, with the host genetic composition and immunobiological status contributing to the process.1,2 All multicellular organisms have the potential to develop cancer. Neoplasia is the process of abnormal growth that starts from a single altered cell.8 A neoplasm is an abnormal mass of tissue that results when cells divide more than they should or do not die when they should. Neoplasms may be benign or malignant, depending on their biological activity. Benign neoplasms cannot spread by invasion or metastasis—they only grow locally. Malignant neoplasms are capable of spreading by invasion and metastasis. By definition, the term “cancer” applies only to malignant tumors.8 |

ODs on the Lookout

Ocular manifestations of gliomas and GBM are similar to those of other space-occupying lesions and may include any of the following:

- Headache

- Blurred vision

- Visual field loss (defects correlate with site of tumor)

- Spatial neglect

- Cranial nerve palsies

- Optic disc edema and atrophy

- Pupillary abnormalities, including RAPD

- Gaze-induced nystagmus

Clinical evaluation is crucial for these patients, particularly a thorough review of systems, including questions of weight loss, dizziness, headache, muscle weakness, loss of appetite, malaise, etc. Clinical evidence of progression can actually precede magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence in both initial and recurrent GBM, with seizures being the most common preceding symptom.4 One study of two cases found distinct, progressive visual field defects predated neuroimaging identification of tumor progression.5 Thus, new or worsening field defects may indicate signs of tumor progression in GBM and should prompt further investigation.

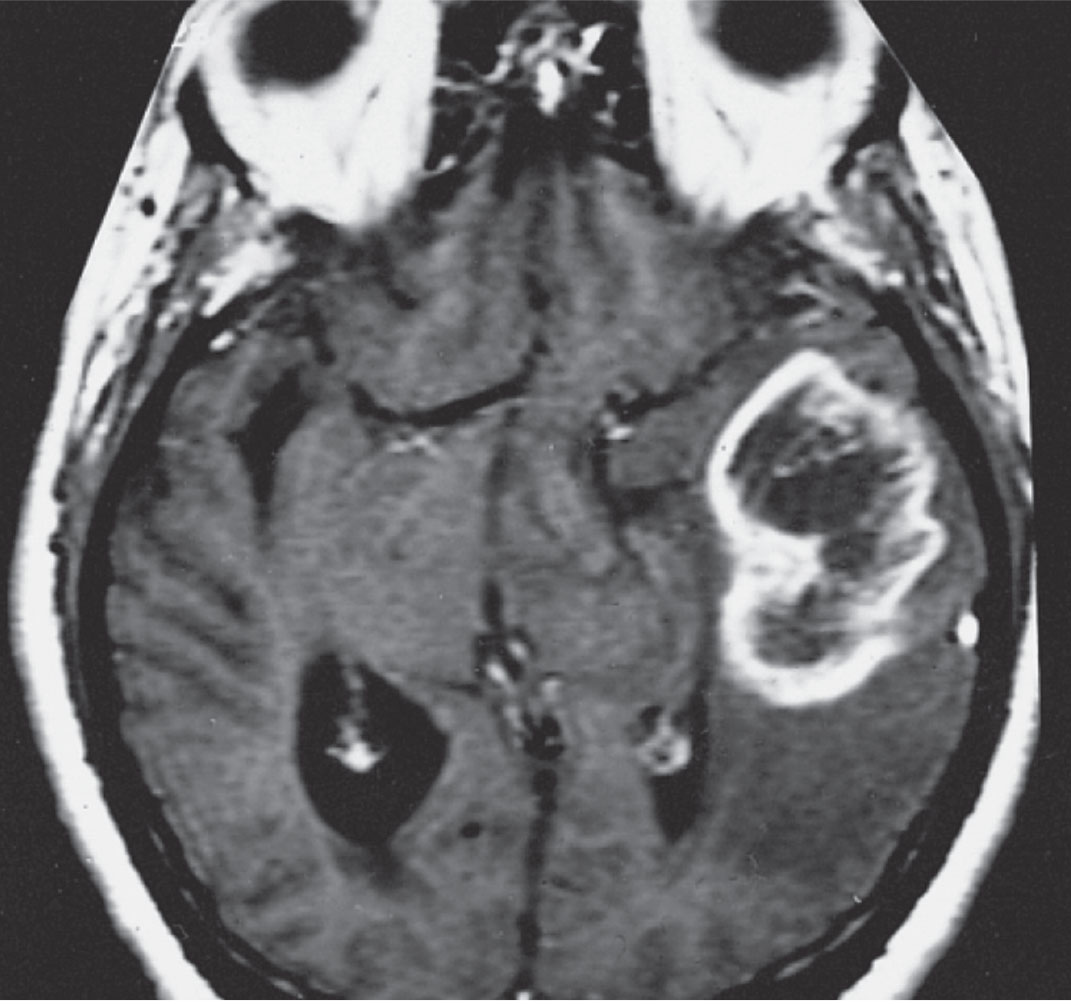

Patients suspected of having GBM or other space-occupying conditions should undergo neuroimaging studies such as computed tomography, MRI with and without contrast, positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain (Figure 2).6

Obtaining tumor genetics with electroencephalography, lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid studies may also be useful for predicting response to adjuvant therapy.

|

| Fig. 2. MRI of GBM in a different patient showing a ring-shaped zone of contrast enhancement around a dark central area of necrosis. Image: The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. |

Although no curative treatment for GBM exists, the standard therapy consists of maximal safe surgical resection, radiotherapy and concomitant and adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide.3,6 The addition of radiotherapy to surgery increases patient survival, and adjuvant chemotherapy shows a significant survival benefit in more than 25% of patients.7 However, clinicians must balance these therapies with quality of life issues, and in patients aged 70 or older, less aggressive therapy with radiation or temozolomide alone may be considered.

A patient diagnosed with GBM should be treated and managed by an interprofessional team that includes neurosurgeons, neurologists, neuro-oncologists, neuroradiologists, neuropathologists, radiation oncologists, physical therapists, social workers and other specialists with advanced training and extensive experience in brain tumors. ODs can and should be vital members of that team, beginning with diagnosis and continuing through comanagement and visual field enhancement.

|

1. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97-109. 2. McLendon RE, Halperin EC. Is the long-term survival of patients with intracranial glioblastoma multiforme overstated? Cancer. 2003;98(8):1745-8. 3. Cornett PA, Dea TO. Cancer. In: McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds. 2010 Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment. 49th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:1450-1511. 4. Hanif F, Muzaffar K, Perveen K, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme: A review of its epidemiology and pathogenesis through clinical presentation and treatment. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prevention. 2017;18(1):3-9. 5. Chittiboina P, Connor DE Jr, Caldito G, et al. Occult tumors presenting with negative imaging: analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(6):1195-1203. 6. Xie K, Liu CY, Hasso AN, Crow RW. Visual field changes as an early indicator of glioblastoma multiforme progression: two cases of functional vision changes before MRI detection. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ). 2015;9:1041-7. 7. Davis ME. Glioblastoma: overview of disease and treatment. Clin J Oncol Nursing. 2016;20(5):S2-S8. 8. Vitucci M, Hayes DN, Miller CR. Gene expression profiling of gliomas: Merging genomic and histopathological classification for personalised therapy. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:545-53. |