|

History

An 81-year-old Caucasian female reported to the office with a chief complaint of a red and painful left eye of two weeks duration. The patient had been to multiple eye doctors previously for herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratopathy and was treated for a non-healing epithelial defect with active HSV keratitis and subsequent elevated pressure in the left eye. Her ocular history was also remarkable for keratoconjunctivitis sicca in both eyes, for which she had been using artificial tears and erythromycin ointment in both eyes, and half-strength dose of fluorometholone drops in the right eye. The patient developed HSV keratitis about 30 years ago with multiple episodes of exacerbation and remission. Her systemic history was remarkable for herpes simplex virus treated with oral valacyclovir periodically during outbreaks. She denied any allergies.

Diagnostic Data

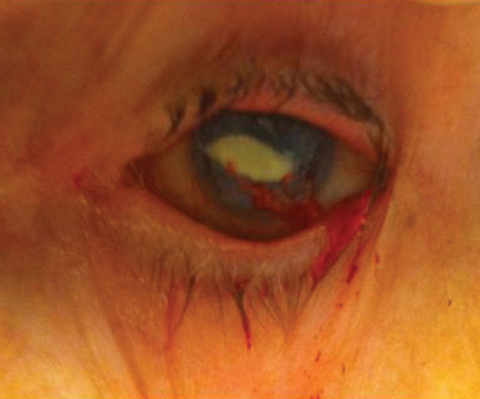

Her best-corrected visual acuities were 20/50 OD and 20/200 OS. Her external examination was grossly intact. The pertinent anterior segment findings in the left eye are demonstrated in the photographs. Biomicroscopy of the right eye showed evidence of anterior basement membrane dystrophy with old inactive corneal opacities. The anterior chamber of the right eye appeared to be deep and quiet with a well-placed posterior chamber intraocular lens. Goldmann intraocular pressures were measured to be 18mm Hg OD and 20mm Hg OS. Dilated funduscopy was within normal limits, both eyes, revealing slightly high asymmetric cup-to-disc ratios measuring 0.5/0.5, 0.55/0.6, OD, OS respectively with normal peripheries.

Your Diagnosis

Does the case presented require any additional tests, history or information? What steps would you take to manage this patient? Based on the information provided, what would be your diagnosis? What is the patient’s most likely prognosis?

|

| An 81-year-old with a history of herpes simplex keratopathy presented with a bleeding, painful left eye. What can these images and her history tell you about her likely diagnosis? Click top image to enlarge. |

|

Diagnosis and Discussion

Additional clinical observation revealed Herbert’s pits of the conjunctiva in both eyes as well as with subconjunctival fibrosis OD>OS. Biomicroscopy of the left eye uncovered 2+ injection of the bulbar conjunctiva with a large central non-healing epithelial defect with mild stromal haze (disciform keratitis). Diffuse confluent pigmented keratic precipitates were noted on the corneal endothelium. The anterior chamber appeared deep with mild flare and trace cell. There was a dense leucocyte plaque with bleeding corneal neovascularization in the left eye.

The diagnosis in this case is herpes simplex keratitis with a non-healing epithelial defect and disciform inflammation, with bleeding corneal neovascularization in the left eye.

Herpes simplex keratitis is an infection of the cornea caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV).1-10 HSV is a ubiquitous large double-stranded DNA virus with high affinity for sensory ganglion cells.3 The virus has a state of latency with periodic reactivation. Some studies have suggested that the cornea may also be a site of HSV latency and replication.4 Keratitis caused by HSV infection is the most common cause of cornea-derived blindness in developed nations.6 A variety of clinical manifestations result from HSV corneal infection. Examples include epithelial keratitis, neurotrophic keratopathy, necrotizing stromal keratitis, immune stromal keratitis, and endotheliitis.1-9

The major immune response to HSV is thought to be T-lymphocyte mediated with CD8 cells playing a protective role and CD4 cells enhancing pathogenesis.5,8

Diagnostic testing is seldom needed in the epithelial presentation due to its classic clinical features. Prior to The Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) of the National Eye Institute of The National Institutes’ of Health, the standard therapy for all forms of HSV keratitis was topical antiviral agents. Completed in several sections, The HEDS assessed the role of topical steroids, oral treatment and the potential for prolonged oral treatment to prevent additional ocular herpes simplex outbreaks.6,9,10

HEDS I showed that adding topical prednisone sodium phosphate to the already initiated regimen of topical antiviral medication was helpful in treating patients with iritis and stromal keratitis. 1,6,9,10 The study also revealed that there was no benefit to adding oral acyclovir in these cases acutely.1,9 While topical prednisone sodium phosphate was the agent used in the study, today, any of the topical steroids can be considered so long as topical anti-viral therapy is already in place. 1,6,9,10

HEDS II showed that oral acyclovir used in a prophylactic dosage over an extended period of time reduced the rate of recurrence of any form of ocular herpes in the following year by 41% and stromal keratitis by 50%.6,9,10 The risk of multiple recurrences decreased from 9% to 4%.6,9,10 Although there was no rebound increase in keratitis after discontinuation of the oral acyclovir, the protection only persisted for a short time once the acyclovir was discontinued.1,7,9

Prompt and appropriate treatment is important to protect visual function and minimize the risk of scarring. Aggressive topical and systemic antivirals along with steroids are necessary for cases demonstrating aggressive inflammation. Treatment begins with the use of topical antiviral medication to decrease the viral load. In September 2009, the FDA approved Zirgan (ganciclovir gel 15%, Sirion Therapeutics) for acute herpetic keratitis (dendritic ulcers). Its dosage is one drop five times daily until resolution of the ulcer, then three times daily for another seven days. Gentle debridement is a good adjunct therapy for decreasing inflammation and scarring when cells are poorly adherent.10 Stopping toxic medications, punctual occlusion, tear film supplementation, bandage contact lenses, biologic contact lens technology, the addition of oral antiviral medications and amniotic membrane transplantation can be helpful in assisting epithelial defect resolution in more severe cases or for presentations that do not resolve with standard therapies. Surgery is indicated in cases with vision threatening scarring, persistent non-healing lesions or when there is risk of impending perforation from necrotizing keratitis.10

In this case, the intracorneal neovascularization was produced secondary to the longstanding non-healing cornea defect. The discomfort level of the patient and the presence of chronically compromised vessels led the corneal specialist to consider a conjunctival flap versus a temporary tarsorrhaphy versus amniotic membrane transplantation versus penetrating keratoplasty. The surgeon concluded that the best approach would be amniotic membrane graft.

At the one-week follow-up significant improvement was apparent. Intraocular pressure was monitored at all visits and the condition resolved over the course of 8 months without complication yielding a final visual acuity of 20/50. The patient has remained on low dose oral antiviral therapy to protect against recurrence.

Dr. Gurwood thanks Dr. M. Selehi for contributing this case.

| 1. Wang X, Wang L, Wu N, Ma X, Xu J.A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for iridocyclitis caused by herpes simplex virus. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Arch opthalmol. 1996;114(9):1065-72. 2. Benerjee K, Biswas PS, Rouse BT. Elucidating the protective and pathologic T cell species in the virus-induced corneal immunoinflammatory condition herpetic stromal keratitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:24-32. 3. Cowan FM, French RS, Mayaud P, et al. Seroepidemiological study of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in Brazil, Estonia, India, Morocco, and Sri Lanka. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:286-90. 4. Kaye SB, Lynas C, Patterson A, et al. Evidence for herpes simplex viral latency in the human cornea. Br. J ophthalmol. 1991;75:195-200. 5. Mott KR, Chentoufi AA, Carpenter D, et al. The role of a glyco-protein K (gK) CD8+ T-cell epitope of herpes simplex virus on virus replication and pathogenicity, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(6):2903-12. 6. NEI. Facts about the corneal and corneal disease. www.nei.nihgov/health/corneadisease. 7. Sheppard JD, Wertheimer ML, Scoper SV. Modalities to decrease stromal herpes simplex keratitis reactivation rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(7):852-6. 8. Stuart PM, Summers B, Morris JE, et al. CD8(+) T cells control corneal disease following ocular infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2055-63. 9. Wilhelmus KR, Dawson CR, Barron BA, et al. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis recurring during treatment of stromal keratitis or iridocyclitis Herpetic eye Disease Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol.1996;80:969-72. 10. Wilhelmus KR. The treatment of herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:505-32. |