A 37-year-old female is diagnosed with pigmentary glaucoma. Her optic discs and visual fields are only minimally damaged, despite pretreatment intraocular pressure of 45mm Hg in each eye. She has been treated successfully with a topical prostaglandin analog, which reduced her IOP to 18mm Hg O.U. After two years of successful therapy, she reports being eight weeks pregnant.

Do you continue her successful therapy? Are there safer options?

We rarely see pregnant patients who have glaucoma. However, more women are electing to have babies later in life. Also, because secondary glaucomas can afflict younger patients, you may encounter such a patient.

Therapeutic treatment of a pregnant patient affects two lives, and there are separate issues for pregnancy and nursing. But, knowledge of the safety of topical glaucoma medications in pregnancy and nursing is often limited to anecdotal case reports.

In a survey-based study, only 25% of ophthalmologists had experience treating pregnant glaucoma patients. Of these, 71% continued pre-pregnancy treatment, and 34% observed the patient. When asked what they would currently do, 31% said they were uncertain.1

In this months column, we will attempt to demystify the safety of glaucoma treatment of the pregnant patient.

Safety Assessment

Little is known about the teratogenic effects of glaucoma medications, and there are few human studies that specifically examine the fetus for harm from glaucoma medications.2 However, the risk of giving ophthalmic drugs to pregnant women appears to be low.3

|

| The risk of giving ophthalmic drugs to a pregnant patient appears low. |

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration Safety Assessment of all medications in pregnancy ascribes each medication to a specific class, namely:

Class A, which have proven safety in human studies.

Class B, which indicates presumed safety based upon animal studies.

Class C, which indicates uncertain safety, with adverse effects seen in animal studies but not in human studies.

Class D, which are considered unsafe, although the risk may be justified in certain circumstances.

Class X, which indicates a high lack of safety, with risks outweighing possible benefits.

Most topical glaucoma medications are class C, except for brimonidine and dipivefrin (both are Class B). No topical ophthalmic medication is categorized as either Class A or X.2

Prostaglandin Analogs

Prostaglandin analogs are Class C drugs. There are no reports of untoward human fetal effects using this medication class. However, the use of prostaglandin analogs is ill-advised in all stages of pregnancy, as these compounds may cross the blood-placental barrier and are known to be important factors in controlling physiological changes in the mother and baby during labor. Specifically, prostaglandins are known to be involved in stimulating uterine contraction, and therefore are not an option for first-line therapy. Exogenously applied prostaglandins are used in cervical ripening and labor induction.4-6

In theory, topical prostaglandins may induce labor, though this has not yet been seen. One small study examining latanoprost exposure during pregnancy showed no ill effects to the neonate in nine cases, though one patient suffered a miscarriage. However, the medication was not specifically identified as being causative.7

Beta-Blockers

Very little has been in the literature regarding adverse fetal effects of topical beta-blockers. In one report, the 21-week-old fetus of a mother using topical timolol showed bradycardia and arrhythmia. These effects were possibly due to the use of timolol.8 However, numerous cases show timolol has been used safely in pregnancy.2

There is more concern about topical beta-blocker use when nursing than during pregnancy. Timolol has been detected in breast milk at a higher concentration than in plasma, though at 1/80 of the cardiac-effective dose.9

Topical beta-blockers likely should be avoided early in pregnancy (i.e. first trimester) and then used only if absolutely necessary in later pregnancy stages and postpartum. The fetus/newborn must be monitored closely for signs of apnea and bradycardia.

Alpha-Adrenergic Agonists

Brimonidine, the most commonly prescribed alpha-adrenergic agent, is a Class B medication, making it one of the safer medications to use during pregnancy.

However, brimonidine may cross the placental barrier, and we do not know if it is secreted in breast milk. So, use extreme caution in patients who breastfeed, as brimonidine has been associated with central nervous system depression in infants and neonates.10,11

Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

Acetazolamide has been found in breast milk at one-third the plasma level of the mother, though it is extremely low in the infants plasma level after breast feeding, making it appear safe in breastfeeding.12

However, there are reports of fetal renal and metabolic disorders from use during pregnancy.13,14 So, the pregnant patient should avoid carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) during pregnancy.

There appear to be no reported cases of fetal adverse effects (nor successful use) of topical CAIs in pregnancy. However, topical use of dorzolamide was reported to cause metabolic acidosis in a five-day-old male using the medication for congenital glaucoma.15

We do not know whether topical CAIs are excreted in breast milk. However, because there is such a potential for secretion in breast milk, there may be danger in their use by patients who breastfeed.

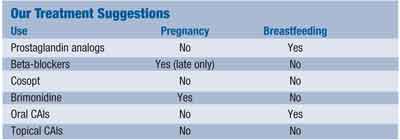

Unfortunately there is no consensus on topical glaucoma management in these patients.1 (See Our Treatment Suggestions, above.)

In some cases, discontinuation of therapy may be acceptable, as IOP tends to reduce during pregnancy.16,17 But, in a case in which pre-treatment IOP was 45mm Hg, simple observation is not an option.

Glaucoma treatment in pregnant and nursing patients must be tailored to each individual patient, with a detailed discussion of the options and risks. Informed consent and close communication with the patients OB/GYN are appropriate here. Often, laser or surgical therapies are better alternatives. Indeed, this patient was referred for selective laser trabeculoplasty and discontinuation of the prostaglandin analog.

Drs. Kabat and Sowka are members of Alcons speakers alliance and on VSPs approved speakers list. Dr. Kabat is on the Board of Optometric Consultants for Cynacon/OCuSOFT. Dr. Sowka is a member of Carl Zeiss Meditecs Speakers Bureau and a paid consultant for Carl Zeiss. They have no financial interest in any of the products mentioned.

1. Vaideanu D, Fraser S. Glaucoma management in pregnancy: a questionnaire survey. Eye 2005 Nov 25; [Epub ahead of print]

2. Maris PJ Jr, Mandal AK, Netland PA. Medical therapy of pediatric glaucoma and glaucoma in pregnancy. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 2005 Sep;18(3):461-8.

3. Chung CY, Kwok AK, Chung KL. Use of ophthalmic medications during pregnancy. Hong Kong Med J 2004 Jun;10(3):

191-5.

4. Mackenzie IZ. Induction of labour at the start of the new millennium. Reproduction 2006 Jun;131(6):989-98.

5. Briggs GG, Wan SR. Drug therapy during labor and delivery, part 1. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2006 Jun 1;63(11):1038-47.

6. Chen J, Senior J, Marshall K, et al. Studies using isolated uterine and other preparations show bimatoprost and prostanoid FP agonists have different activity profiles. Br J Pharmacol 2005 Feb;144(4):493-501.

7. De Santis M, Lucchese A, Carducci B, et al. Latanoprost exposure in pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol 2004 Aug;138(2): 305-6.

8. Wagenvoort AM, van Vugt JM, Sobotka M, et al. Topical timolol therapy in pregnancy: is it safe for the fetus? Teratology 1998 Dec;58(6):258-62.

9. Lustgarten JS, Podos SM. Topical timolol and the nursing mother. Arch Ophthalmol 1983 Sep;101(9):1381-2.

10. Berlin RJ, Lee UT, Samples JR, et al. Ophthalmic drops causing coma in an infant. J Pediatr 2001 Mar;138(3):441-3.

11. Carlsen JO, Zabriskie NA, Kwon YH, et al. Apparent central nervous system depression in infants after the use of topical brimonidine. Am J Ophthalmol 1999 Aug;128(2):255-6.

12. Johnson SM, Martinez M, Freedman S. Management of glaucoma in pregnancy and lactation. Surv Ophthalmol 2001 Mar-Apr;45(5):449-54.

13. Ozawa H, Azuma E, Shindo K, et al. Transient renal tubular acidosis in a neonate following transplacental acetazolamide. Eur J Pediatr 2001 May;160(5):321-2.

14. Merlob P, Litwin A, Mor N. Possible association between acetazolamide administration during pregnancy and metabolic disorders in the newborn. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1990 Apr;35(1):85-8.

15. Morris S, Geh V, Nischal KK, et al. Topical dorzolamide and metabolic acidosis in a neonate. Br J Ophthalmol 2003 Aug;87(8):1052-3.

16. Avasthi P, Sethi P, Mithal S. Effect of pregnancy and labor on intraocular pressure. Int Surg 1976 Feb;61(2):82-4.

17. Green K, Phillips CI, Cheeks L, et al. Aqueous humor flow rate and intraocular pressure during and after pregnancy. Ophthalmic Res 1988; 20:353-7.