|

Many have debated whether all acute isolated ocular motor cranial neuropathies in patients older than 50 with or without vascular factors should undergo neuroimaging. While conventional wisdom demonstrates that isolated third, fourth and sixth cranial neuropathies are a frequent cause of presumed microvascular ischemia, identifiable causes of non-microvascular mononeuropathies have ranged from 1% to 15%.1-3 Based on these findings, some authors offer evidence to suggest the clinical rationale for imaging all acute isolated third, fourth and sixth nerve palsies.

|

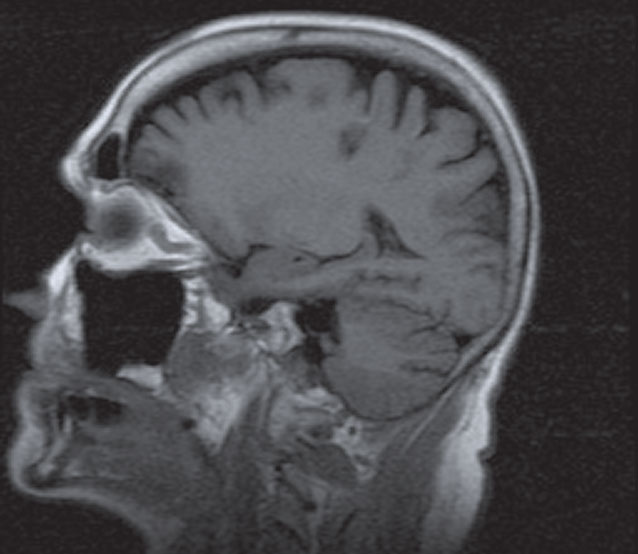

| Three dark lesions within the frontal-parietal-occipital region represents edema from ischemia in a patient with acute, isolated SNP. |

Third Nerve Palsy

The third nerve’s two major functions are oculomotor and pupillo-motor. Both partial and complete third nerve palsy (TNP) can be a manifestation of presumed ischemia in the setting of diabetes, hypertension and more serious pathology.4 Common pathologies involving the oculomotor nerve include ischemic and hemorrhagic infarctions, aneurysm, cavernous malformation and demyelinating disease.5

Knowing which cases require neuroimaging can be thought-provoking, as many have debated which cases need emergent testing. TNP can be differentiated as either partial or complete and pupil-sparing or pupil-involving. While acute headache and TNP may suggest an ominous cause, cases report co-involvement in as few as 30% of patients with aneurysmal TNP and in up to 50% with presumed microvascular cause. Aneurysms are likely to affect pupillo-motor fibers in complete TNP but spare its function in superior division palsies.6 Conversely, up to 20% of patients with microvascular TNP may have pupil involvement, with anisocoria of 1.5mm or less.6 The relative incidence of aneurysm as a cause of isolated TNP ranged from 14% to 56%.7,8 While evidence supports observation in acute, complete, isolated TNP without pupil involvement, numerous cases implicate midbrain strokes, neoplasms, infections, vasculitis, pituitary apoplexy and carotid artery occlusion.

Our recommendation is to obtain an emergent neuroimaging with computed tomography (CT) computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/ magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in all cases of TNP. In ambiguous cases, it is vital that a neuroradiologist interprets the study before one discounts an aneurysm.

Fourth Nerve Palsy

The most common causes of fourth nerve palsy (FNP) are congenital, traumatic and vasculopathic. While the etiology of truly isolated FNP in older patients is often vasculopathic, many report isolated palsies as manifestations of midbrain hemorrhages, pituitary macroadenoma, posterior fossa tumors, dural fistulas, schwannomas and cavernomas.9-17

A small number of isolated FNP cases were identified as having a trochlear nerve schwannoma, as well as etiologies which included cavernous meningioma, intra-cavernous carotid artery aneurysm and a carotid-cavernous fistula.13,18,19,20 While it may be reasonable to observe truly isolated cases, one might miss an important lesion, especially if the patient were to develop additional neurologic symptoms. We recommend that contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain be obtained, with attention to the cavernous sinus.

Sixth Nerve Palsy

Sixth nerve palsy (SNP) is the most common ocular motor nerve palsy.21 The etiology of SNP is most often attributed to ischemia; however, a brain MRI is not routinely performed in all patients. Non-microvascular causes of SNP may include: demyelinating disease, metastasis, aneurysm and intracranial hypertension.22 However, because hypertension and diabetes cause SNP in up to 35% of patients, some argue that monthly follow ups are the best approach in the absence of associated neurologic findings or history of cancer sans MRI confirmation.23,24 Additionally, research shows the potential for spontaneous recovery of SNP in the presence of extramedullary compression by a tumor at the base of the brain.25

Published research does not support observation alone. With the risk of delaying a potential serious intracranial pathology, we recommend obtaining an initial contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain in those with acute isolated SNP, as previous studies have shown a lack of diagnostic benefit from computed tomography (CT).26

Discussion

With the advent of MRI, it’s now possible to detect small ischemic, inflammatory and space-occupying lesions that would have been missed on CT. Observation seemed reasonable since much of the past literature identified a low rate of non-ischemic causes in isolated neuropathies.2 However, in a review of all MRIs ordered for varying ophthalmologic pathologies, 28% of patients had relevant findings, like demyelinating disease, stroke and metastases.27

Until recently, no well-designed studies or prospective case series existed. One study followed patients with acute, non-traumatic, isolated ocular motor nerve palsies.28 Of the 66 patients, nine had significant causes: four patients with third nerve palsy, two of which were pupil-involving; one patient with fourth nerve palsy and four patients with sixth nerve palsy. Excluding pupil-involving TNP, the study identified 11% of patients with a significant etiology, including neoplasm, brainstem infarct, demyelinating disease and pituitary apoplexy.28 We believe there is sufficient data for arguing that all acute cranial nerve palsies undergo imaging, regardless of the lack of associated neurological symptoms.

One observational case series estimated the proportion of patients suffering from isolated ocular motor nerve palsies from presumed microvascular ischemia versus other causes by using contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain in patients 50 and older with acute isolated third, fourth and sixth nerve palsies.3 Due to advances in medical and surgical management, these patients benefitted from early diagnosis.

Possible exceptions for ordering imaging may include a combination of the following: no insurance coverage in patients older than 50 with isolated fourth or sixth nerve palsies, positive vasculopathic risk factors, low risk medical history and palsies that resolve within three months.

Each clinician must know their threshold for imaging. High quality neuroimaging is now safe, accessible and readily available, and withholding a possibly life-saving diagnosis seems counterintuitive. While a “normal” imaging study may seem useless, it can provide both a psychological and emotional benefit for the patient and clinician.

1. Patel SV, Mutyala S, Leske DA, et al. Incidence, associations, and evaluation of sixth nerve palsy using a population-based method. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:369–75. 2. Bendszus M, Beck A, Koltzenburg M, et al. MRI in isolated sixth nerve palsies. Neuroradiology.2001;43:742–5. 3. Tamhankar MA, Biousse V, Ying GS, et al. Isolated third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies from presumed microvascular versus other causes: a prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2013; 120(11):2264–2269. 4. Jacobson DM, McCanna TD, Layde PM. Risk factors for ischemic ocular motor nerve palsies. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:961-966. 5. Bruce BB, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Third nerve palsies. Semin Neurol 2007;27:257–68. 6. Trobe JD. Managing oculomotor nerve palsy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:798-802. 7. Lee AG, Hayman LA, Brazis PW. The evaluation of isolated third nerve palsy revisited: an update on the evolving role of magnetic resonance, computed tomography, and catheter angiography. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:137-157. 8. Mathew MR, Teasdale E, McFadzean RM. Multidetector computed tomographic angiography in isolated third nerve palsy. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1411-15. 9. Galetta SL, Balcer LJ. Isolated fourth nerve palsy from midbrain hemorrhage: case report. J Neuroophthalmol. 1998;18:204- 205. 10. Petermann SH, Newman NJ. Pituitary macroadenoma manifesting as an isolated fourth nerve palsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:235-236. 11. Krohel GB, Mansour AM, Petersen WL, et al. Isolated trochlear nerve palsy secondary to a juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1982;2:119-123. 12. Mielke C, Alexander MS, Anand N. Isolated bilateral trochlear nerve palsy as the first clinical sign of a metastatic [correction of metastasic] bronchial carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(4):593-4. 13. Selky AK, Purvin VA. Isolated trochlear nerve palsy secondary to dural carotid-cavernous sinus fistula. J Neuroophthalmol. 1994;14:52-54. 14. Feinberg AS, Newman NJ. Schwannoma in patients with isolated unilateral trochlear nerve palsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:183-188. 15. Maurice-Williams RS. Isolated schwannoma of the fourth cranial nerve: case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989; 52:1442-1443.2001;132:593-594. 16. Leibovitch I, Pakrou D, Selva D, et al. Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of intracranial cavernous hemangiomas. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16:148-152. 17. Surucu O, Sure U, Mittelbronn M, et al. Cavernoma of the trochlear nerve. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:791-793. 18. Feinberg AS1, Newman NJ. Schwannoma in patients with isolated unilateral trochlear nerve palsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(2):183-8. 19. Slavin M. Isolated trochlear nerve palsy secondary to cavernous sinus meningioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:433-4. 20. Arruga J, de Rivas P, Espinet H, Conesa G. Chronic isolated trochlear nerve palsy produced by intracavernous internal carotid artery aneurysm. J Clin Neuro-ophthalmol. 1991;11:104-8. 21. Rosenberg RN. Comprehensive Neurology. New York: Raven Press, 1991. 22. Richards BW, Jones FR, Younge BR. Causes and prognosis in 4,278 cases of paralysis of the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens cranial nerves. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113(5):489–496. 23. Patel S. V., Mutyala S., Leske D. A. et al. Incidence, associations, and evaluation of sixth nerve palsy using a population-based method. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:369-75. 24. Moster ML, Savino PJ, Sergott RC, et al. Isolated sixth-nerve palsies in younger adults. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1328-30. 25. Volpe NJ, Lessell S. Remitting sixth nerve palsy in skull base tumors. Arch Opthalmol. 1993;111:1391–5. 26. Nolan J. Diplopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1968; 52:166-71. 27. Volpe NJ. Socioecomics of neuroimaging in neuroophthalmology. Oral presentation at NANOS Annual Meeting; March 2008; Orlando, FL. collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=180818&q=identifier_t%3A20080313_nanos_diagnostneuroimagsympos_01%2A&fd=title_t%2Ccreator_t%2Cdescription_t%2Cidentifier_t&sort=facet_title_s+asc&facet_setname_s=ehsl_novel_nam. Accessed November 1, 2018. 28. Volpe N. The Work Up of Isolated Ocular Motor Palsy: Who to Scan and Why. Oral presentation at NANOS Annual Meeting; February 2009; Lake Tahoe, CA. pdfs.semanticscholar.org/03f9/295c3712be8cf794492739c9a2d342122427.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018. |