We have all experienced the frustration of caring for a dry eye patient who continues to be symptomatic despite maximal therapy. Before we toss in the towel, we must question if we are missing the underlying condition. This article suggests a new way to assess patients who still struggle with symptoms, and it all begins with a closer look at their eyelid function—and dysfunction.

|

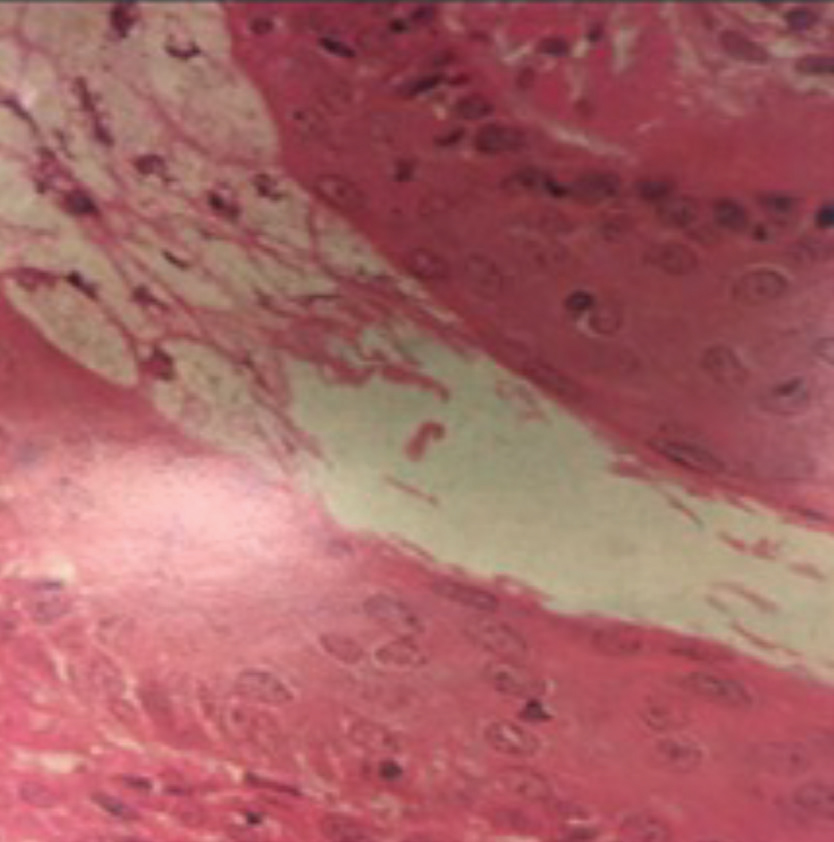

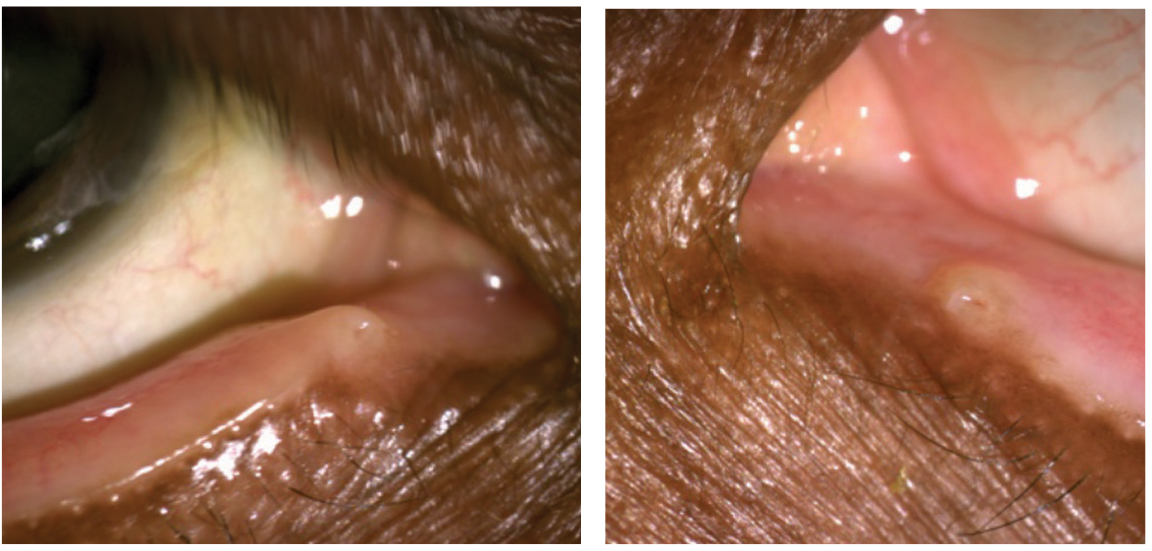

| Keratinized epithelium sheds from the lining of the terminal duct of the meibomian gland before the orifice. This creates a “spiderweb” that can trap meibum as it exits the gland if the force of the blink is insufficient to expel meibum.11 Image by Donald Kprb, OD, and Antonio S. Henriquez, MD, PhD. Click image to enlarge. |

In the setting of a compliant patient without severe structural damage, if a treatment is failing, it might not be because the recommended therapy, medication or device does not work. Rather, it might be a deficiency in how we are defining the patient’s condition. The new definition set forth by the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II is by far the most comprehensive one to date: “Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface.”1

Still, none of the recent definitions for dry eye, including this one, emphasize the crucial role of the eyelids—when they do not function properly, the ocular surface is compromised. The mechanisms by which the eyelids fail to protect the eye are often ignored, and thus otherwise completely reasonable treatments do not improve signs or symptoms of dryness.

|

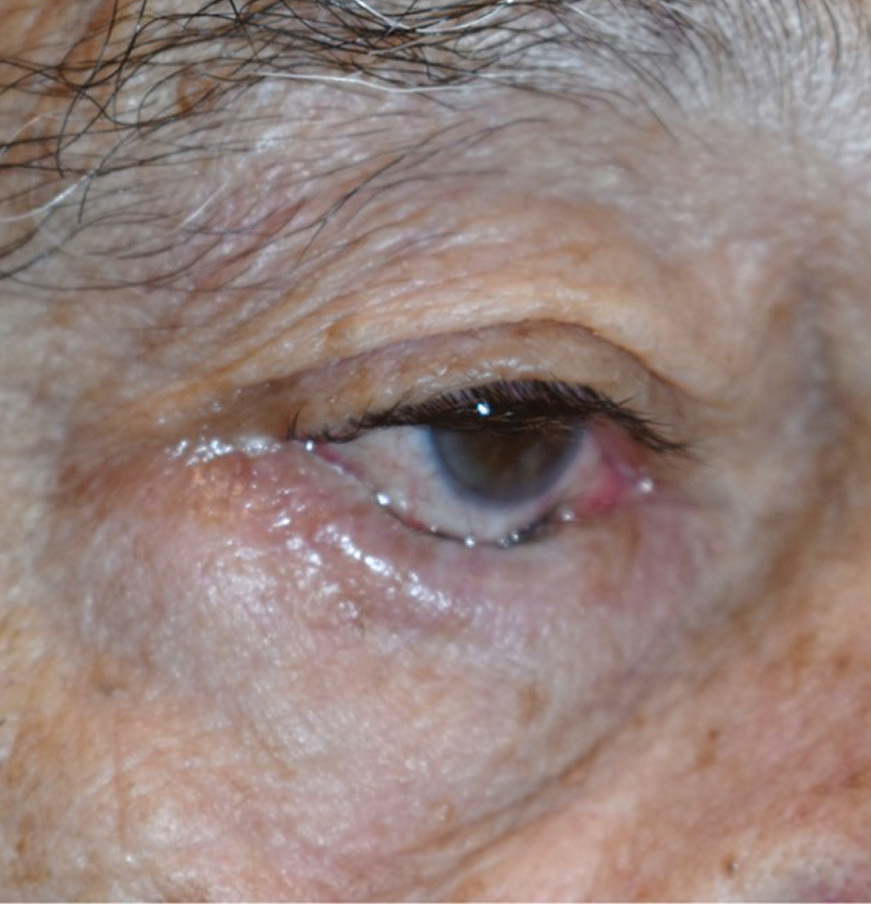

| This patient’s involutional entropion is pushing their lashes into conjunctiva, compromising the ocular surface. Photo by Brent Murphy, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

Take Cover

The eyelids are the primary protectors of the tear film, corneal nerves and conjunctiva. The fully closed eyelid protects and restores the cornea and conjunctiva during sleep, while the blink reflex and cilia protect the eye from harm and foreign objects. The eyelids contain the meibomian glands and some of the accessory lacrimal glands critical for tear film stability. Proper lid closure, innervation and blink mechanisms are designed to produce, mix and spread the tear components across the ocular surface and guide the egress of tear film and debris through the nasolacrimal apparatus.

When the lids fail to do their job, a host of sequelae ensue, including inflammation and symptoms consistent with dry eye disease. Staring or partial blinking, as occurs during prolonged computer use, leads to evaporative (desiccating) stress. Research shows this initiates a dry eye cascade in a murine model exposed to scopolamine and drafty environments with low humidity.2 The study suggests that under these conditions, an immune-mediated stress response occurs within six hours in conjunctival and corneal epithelial cells that leads to activation of natural killer (NK) cells. NK cells produce IFN-γ that signals upregulation of Th1-associated chemokines, which then recruit and activate other inflammatory cells.2

Health, CompromisedStructural eyelid dysfunction isn’t the only way the palpebral conjunctiva can become inflamed. Bacterial invasion causing meibomitis, airborne pollutants, Demodex, ocular rosacea and chronic exposure to allergens, pharmacological toxins, some cosmetics and other chemical exposures, are all possible causes.1-4 In addition, mechanical stressors such as eye rubbing and contact lenses can cause inflammation.5,6 Less commonly seen but well recognized causes of chronic and often severe inflammation include ocular graft-vs.-host disease, Stevens Johnson syndrome and chemical or thermal burns. Controlling any of these other factors is crucial before dry eye disease can be cured instead of just controlled.

|

Because desiccating stress is one of the seminal events in the inflammatory cascade, our dry eye workup should evaluate whether the patient’s eyelids are promoting tear film stability. Two critical questions to ask a patient is how many hours per day they use a screen and if their eyes feel dry when they wake up. If they are staring all day and/or not closing their eyes completely overnight, the tears will evaporate and inflammation is inevitable.

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is the most common way the eyelids can fail to do their job. MGD is caused by obstruction and poor blinking.

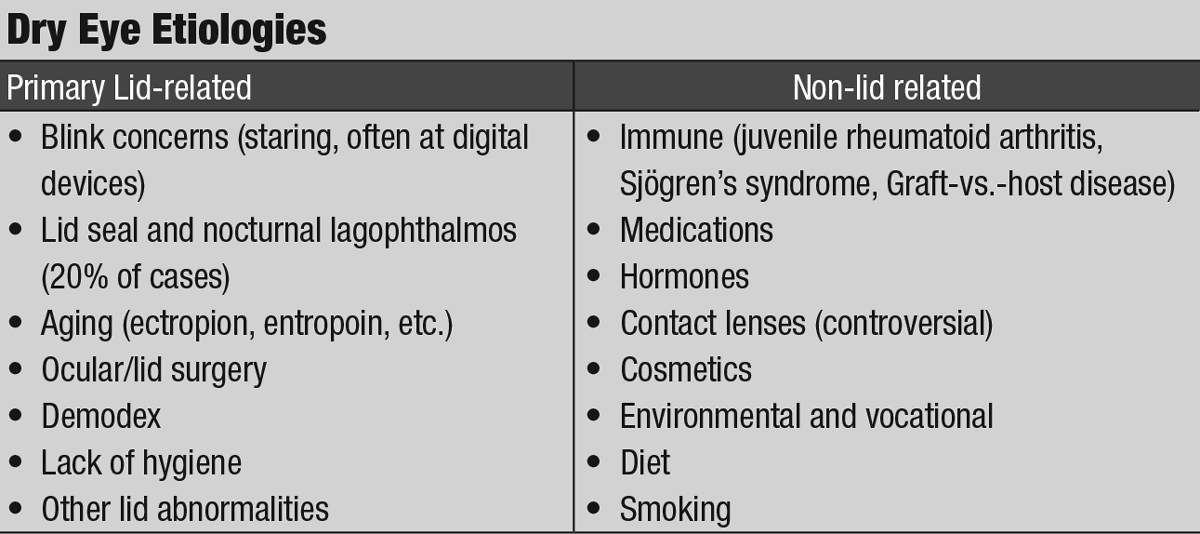

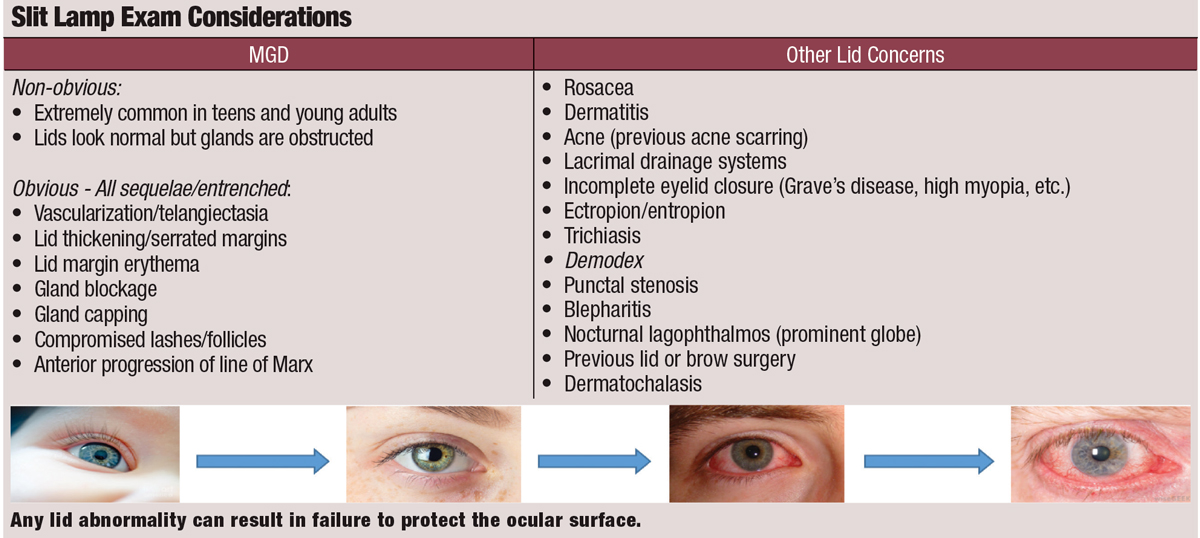

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Obstruction. Epidemiologic evidence shows that aqueous and goblet cell deficiencies are less common than MGD.3 The excitement surrounding meibomian gland rehabilitation as a potential silver bullet for dry eye therapy is evidenced by a host of new methods for rehabilitating the glands. Many clinicians now race to treat MGD as the root cause of dry eye but fail to understand why MGD starts in the first place. Obstruction from the inner aspect of the gland occurs because the keratinized epithelium in the terminal duct accumulates and then traps escaping meibum when the blink is not fully executed.

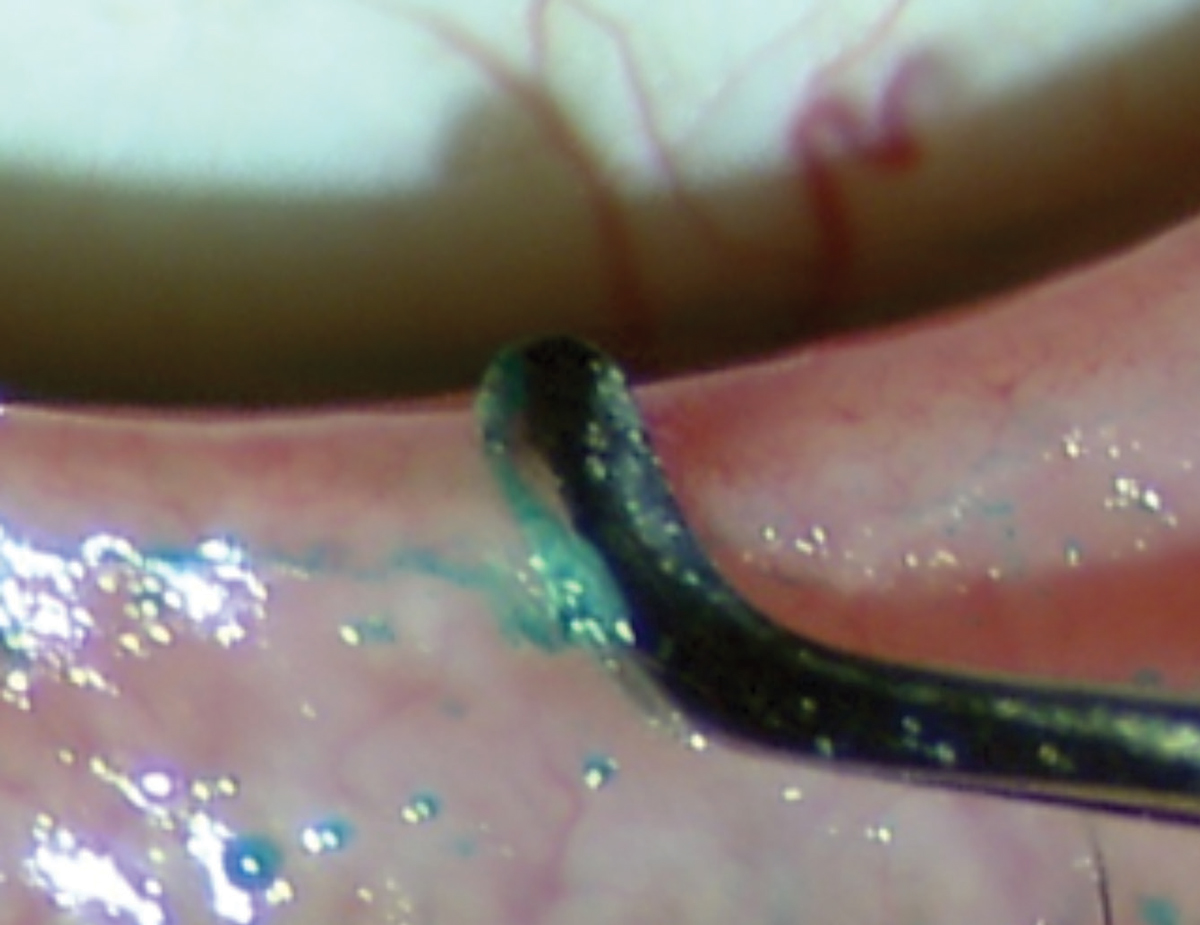

Obstruction from the outer aspect of the gland occurs when desquamated epithelium and biofilms cause inflammation of the lid margin, again because a partial blink does not naturally exfoliate the lid margin surfaces. These dead cells and biofilms eventually cause inflammation of the tissue.4

Both inner and outer obstruction is caused by partial or infrequent blinking, both of which often result from staring at computers, tablets and smartphones. Research shows smartphone use in particular can increase symptoms of dry eye.5

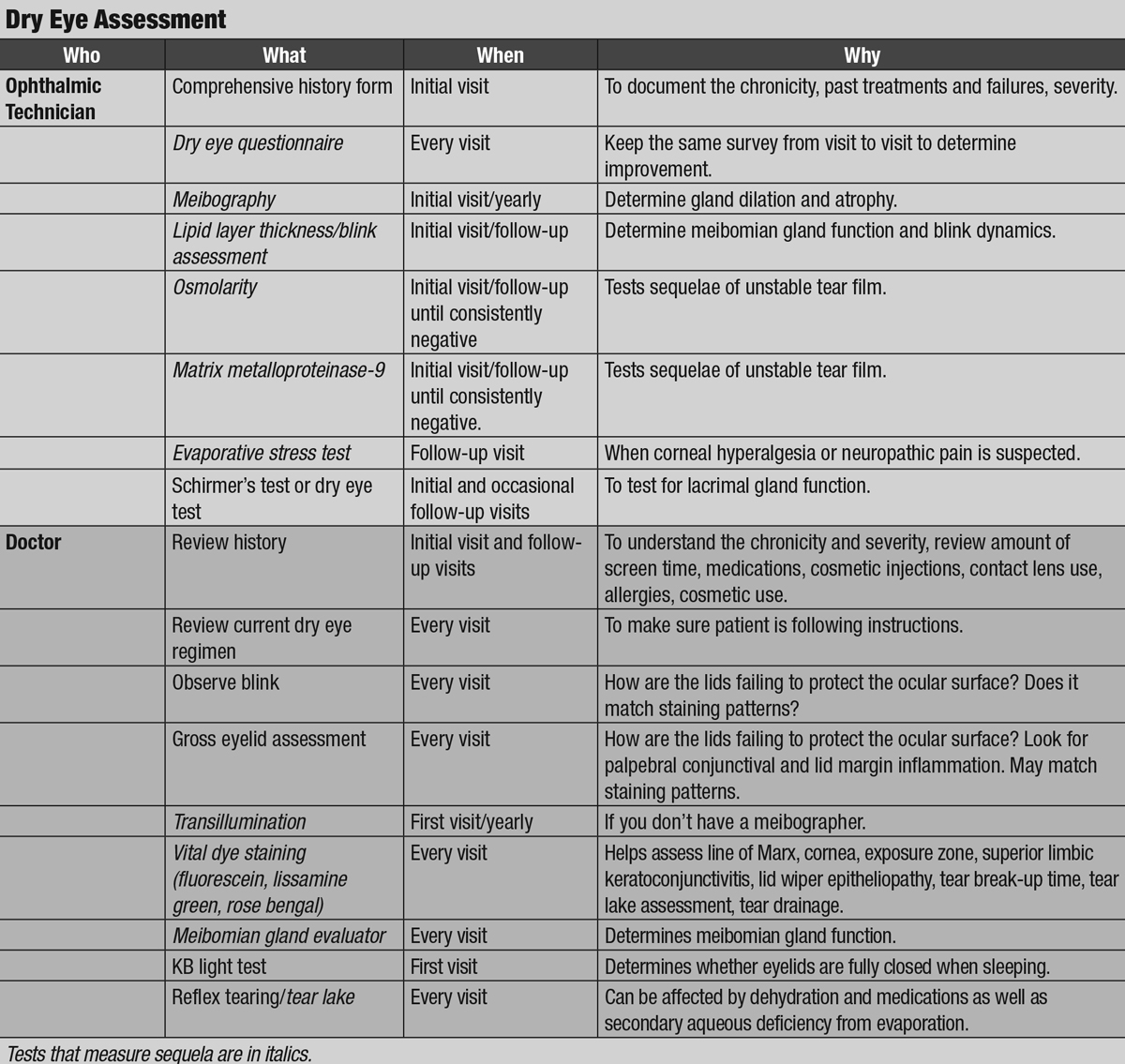

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Lid closure. Complete eyelid closure is required for the meibomian glands to expel their contents, for the tear film to mix and for tears to spread and be removed from the eye. Without proper eyelid closure, the meibomian glands do not produce meibum and the aqueous components evaporate. The solid components of the aqueous phase become more concentrated, resulting in hyperosmolarity. Thus begins the cycle of inflammation and pain.

Myriad conditions can thwart the lids’ ability to adequately protect the ocular surface, including nocturnal lagophthalmos and poor lid seal, age-related lid laxity, floppy eyelid syndrome, senile ectropion or entropion, blepharoplasty, Botox injections, thyroid eye disease, paralysis, high myopia, facial trauma and lid and craniofacial abnormalities.

|

| The Korb-Blackie test indicates incomplete eyelid closure when light is seen emanating from the lid margin of the eye. Photo by Azinda Morrow, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Infrequent and/or partial blinks represent a primary failure of the lids to adequately protect the ocular surface.6When incomplete blinks occur over a period of hours, the ocular surface, subjected to chronic desiccating stress, becomes compromised.

Desiccating stressors are extremely prominent in modern society, mostly due to the ubiquity of digital screen use. Blink rate decreases during screen use, and research shows incomplete blinks occur when looking at screens and reading. The tear film integrity should be sustained longer than the interblink interval; otherwise, the corneal nerves are exposed between blinks causing irritation and, ultimately, hyperalgesia.

No Rest for the WearyExposure keratoconjunctivitis both during the day and at night is a problem for patients who have had aggressive lid surgery, paralysis, trauma, thyroid eye disease or other lid abnormalities. In this instance, the patient likely has incomplete habitual blinks during the day and nocturnal lagophthalmos—never providing the eye with a period of recovery. Some patients will experience corneal erosions and filamentary keratitis. Because the corneal nociceptors can become chronically irritated and hypersensitive to subthreshold stimuli, these cases are at risk for hyperalgesia and corneal neuropathic pain.1 If this is suspected, clinicians can place a patient in a swim goggle for about 30 minutes or instill a drop of proparacaine to determine whether these conditions are present. The corneal nerves must be protected from desiccating stress at all costs for patients with exposure keratoconjunctivitis, and all other comorbid conditions need to be addressed.

|

Patients with poor blinking habits will invariably develop secondary MGD and exhibit inferior corneal staining and conjunctival injection nasally and temporally in the “exposure zone.” Even patients with non-obvious MGD but significant dry eye symptoms can harbor increased numbers of inflammatory cells in the proximal tissue and conjunctiva.7 This suggests that some of the dry eye symptoms may actually stem from the palpebral conjunctiva of the eyelids.

Any ongoing office and at-home treatments for meibomian gland health and ocular surface inflammation will have marginal and short-acting effects unless these root causes of dry eye disease are addressed first.

|

| This patient displays punctal stenosis in both eyes. Photos by Marlon Demeritt, OD, and Beata Lewandowska, OD. |

Assessment, Step-by-step

Current recommendations for dry eye evaluation focus on longitudinal, quantitative metrics captured by questionnaires, vital dye staining, tear film and meibomian gland imaging and testing for inflammation, tear production and osmolarity. While these practice patterns are incredibly useful, they do not stress the importance of eyelid health. Thus, clinicians should re-evaluate their dry eye protocol to ensure it also incorporates careful lid assessment. This includes a determination of every reason that the lids may be failing to protect the surface of the eye by external and slit lamp evaluation using standard techniques.

Rooting out the multifactorial, primary causes of dry eye begins with a thorough case history, including systemic conditions, medications, prior successes and failures with dry eye treatments, use of contact lenses, screen time, exposure to pollutants and cosmetics and any prior lid surgeries or procedures (patients do not often think of cosmetic lid surgery as being relevant). Clinicians should review this comprehensive history at least annually and pair it with a list of all available interventions.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

As part of the case history, it is vital to inquire when the patient experiences their dry eye symptoms. For example, if symptoms occur at the end of the day, clinicians should ask about how the patient is spending their time. The average American adult spends 11 hours per day in front of some type of screen, inevitably compromising their blink.8

If a patient reports that dry eye symptoms occur upon arising or when they get up in the middle of the night, it’s likely that they have nocturnal lagophthalmos and the eyes are not sealed shut. In theory, Bell’s phenomena with its upward movement of the globe during sleep should protect the cornea. However, in one study, fewer than half of the study population exhibited the expected upward rotation.9

Testing for nocturnal lagophthalmos and poor lid seal is readily accomplished using the Korb-Blackie Light Test in which a Finoff transilluminator is applied to the superior sulcus over the closed eyelid in a darkened room.10 The test is positive if light leaks down to the cheek and the patient reports morning symptoms. Some of these patients will manifest inferior corneal staining. In some cases the condition is unilateral, which could explain why they are more symptomatic in one eye. If the patient is having chronic exposure for six to eight hours every night, inflammation eventually occurs, which is further exacerbated by daytime proinflammatory activities such as contact lens wear, cosmetics and digital device use.

|

| Dead skin and biofilm can accumulate on the lid margin surface, causing external orifice obstruction. Image by Donald Korb, OD, and Antonio S. Henriquez, MD, PhD. |

When evaluating the primary causes of dry eye, look to the definitions that help guide our management, but do not neglect the eyelids, which are the true guardians of the ocular surface. They play a pivotal role in protecting the eye from desiccating stress. Clincians should fully educate patients regarding the nature of their dry eye and overall prognosis for improvement. Some patients will not get better because of structural changes, and some patients may take a very long time to recover. Treating problems of eyelid function and structure are key to improving the signs and symptoms of dry eye disease.

Dr. Nau practices at Korb & Associates with a focus on medically necessary contact lenses, anterior segment disease and dry eye.

| 1. Lemp MA. Report of the national eye institute/industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. CLAO J. 1995;21:4:221e32. 2. Coursey TG, Bohat R, Barbosa FL, et al. Desiccating stress-induced chemokine expression in the epithelium is dependent on upregulation of NKG2D/RAE-1 and release of IFN-γ in experimental dry eye. J Immunol. 2014;193(10):5264-72. 3. Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334-65. 4. Rynerson JM, Perry HD. DEBS - A unification theory for dry eye and blepharitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:2455-67. 5. Choi JH, Li Y, Kim SH, et al. The influences of smartphone use on the status of the tear film and ocular surface. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206541 6. Cardona G, García C, Serés C, et al. Blink rate, blink amplitude, and tear film integrity during dynamic visual display terminal tasks. Curr Eye Res. 2011;36(3):190-97. 7. Qazi Y, Kheirkhah A, Blackie C, et al. Clinically relevant immune cell metrics of inflammation in meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalomol Vis Sci. 2018;59(15):6111-23. 8. The Nielsen total audience report: Q1 2018. www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/report/2018/q1-2018-total-audience-report. Accessed December 13, 2019. 9. Sturrock GD. Nocturnal lagophthalmos and recurrent erosion. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976:60(2):97-103. 10. Blackie CA, Korb DR. A novel lid seal evaluation: the Korb-Blackie light test. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41(2):98-100. 11. Korb DR, Henriquez AS. Meibomian gland dysfunction and contact lens intolerance. J Am Optom Assoc. 1980;51(3):243-51. |