42nd Annual Contact Lens ReportFollow the links below to read other articles from annual update on contact lenses: Dissecting the Soft Contact Lens |

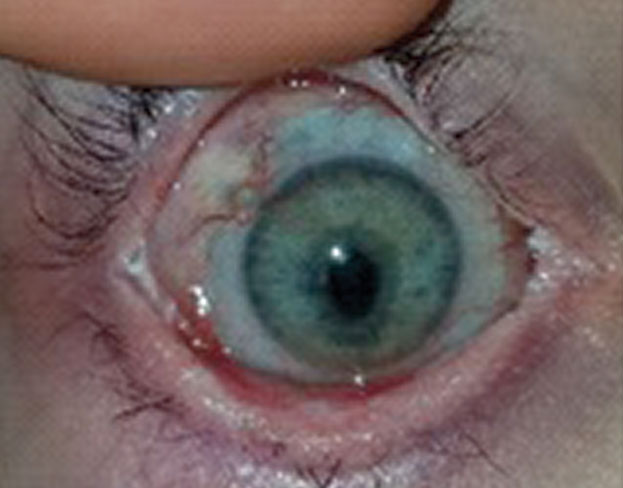

A therapeutic bandage lens is any contact lens used to promote healing, relieve pain and protect the ocular surface. The placement of these therapeutic lenses, whether temporary or as part of a long-term treatment plan, should be thought of as a medical treatment or procedure, rather than a lens per se. It is a medical prosthesis for someone who has been injured, is necessary for the health of the eye (not for vision correction) and can minimize the risk of progressive disability, ocular morbidity or both (Figure 1).

While a rewarding experience, fitting and billing for therapeutic bandage lenses can be complicated. These clinical and coding tips can help you ensure patients receive the coverage they need to heal.

|  |

| Fig. 1. Therapeutic bandage lenses, medical prostheses for injured patients, are not for vision correction. They are a medical treatment to avoid progressive disability, ocular morbidity or both. | Fig. 2. This patient received a bandage contact lens after corneal collagen crosslinking. After removal of the bandage lens, the patient suffered an epithelial defect. |

Defining the Terms

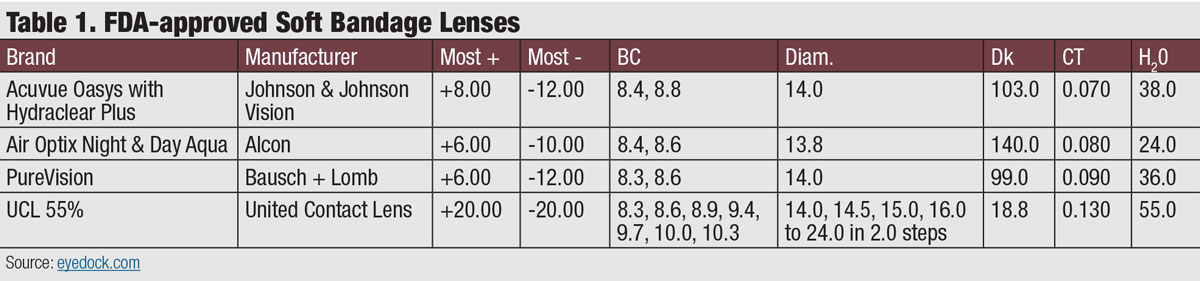

The ocular surface can be protected by several modalities, including a soft contact lens, gas permeable (scleral) lens or even, one day a 3D-printed bio-gel. While some soft lenses have applied for the FDA indication and approval for bandage lenses, newer materials and designs may offer the advantage of a larger variety of parameters, biocompatibility and ocular surface protection (Table 1). Many of these therapeutic devices would be considered off-label use of the material or lens design, but are within the standard of care for treatment of the disease.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

While soft contact lenses are frequently referred to as bandage contact lenses, it is more appropriate to refer to therapeutic scleral lenses as therapeutic scleral prosthetic devices. This terminology helps clarify the distinction between a highly customized device and an off-the-shelf disposable product that requires less skill to fit and which is (generally) replaced more frequently. This distinction also has billing implications.

Choosing a Lens

Soft bandage lenses are often used for wound coverage, such as placement after surgical procedures including superficial keratectomy, phototherapeutic keratectomy and corneal collagen crosslinking. They can also be used for the delivery of drug compounds and management of bleb leaks. Disposable lenses, generally high Dk silicone hydrogel, are commonly used post-surgery to cover the wound and control pain. Disposables, with the advantage of being ubiquitous and inexpensive, can be effective in the treatment of persistent epithelial defects and exposure keratopathy, especially in combination with autologous serum eye drops and punctal plugs, according to research.1-3 Some conditions such as bleb leaks require custom-made soft lenses.

Old Dog, New TricksIn the future, soft bandage contact lenses may be integral for the delivery of drugs, such as antibiotics, anti-glaucoma medications and anti-inflammatory agents. Research shows drug-laden contact lenses can increase the bioavailability of the drug by up to 50%, which eventually reduces the dose, dosing frequency, systemic drug absorption and associated side effects.1 Investigators continue to explore many drug delivery systems, including soaking the lens in the drug, molecular imprinting, nanoparticles and liposomes. Crosslinked hyaluronic acid bandage gels also show promise in corneal healing in extremely compromised eyes.2

|

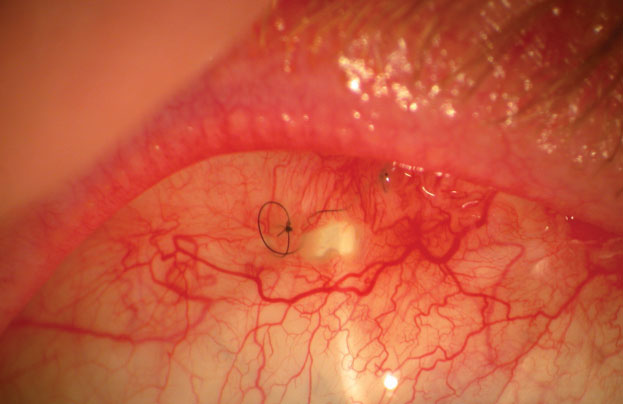

Bleb leaks are a frequent complication after glaucoma surgery, with up to 30% of blebs leaking within the first two months post-procedure.4 The associated complications are quite serious, ranging from hypotony to endophthalmitis. Management of the leak will depend on the location, the rate of aqueous loss and the type of flap and surrounding conjunctival tissue. Serious leaks need to be surgically corrected, but small leaks located close to the limbus may be tamponaded by a soft bandage lens (Figure 3). Clinicians should exercise extreme caution when fitting blebs, as factors such as lens size are crucial to success. The lens must to be large enough to completely cover the leak; otherwise, the wound may increase in size. Similarly, if the lens edge rubs into the bleb, it may cause a bleb erosion.

|

| Fig. 3. Large filtering bleb holes, like this one, require surgical correction. Small holes near the limbus can be managed with therapeutic bandage lenses. |

|

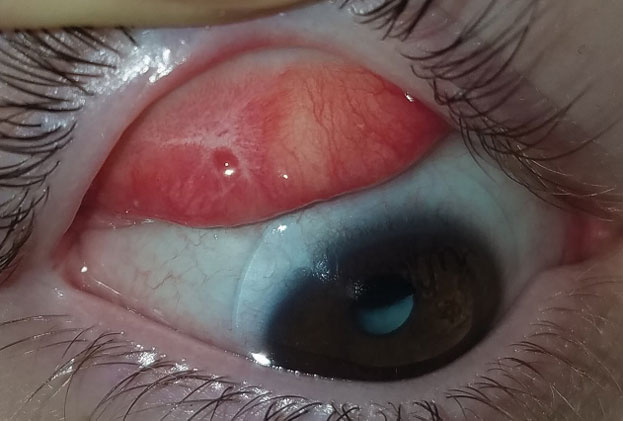

| Fig. 4. This patient with graft vs. host disease has fibrosis of the superior palpebral conjunctiva. Photo: Lee Alward, MD |

Both hydrogel and silicone hydrogel lenses are good bandage lens options for bleb leaks. The lens should cover at least 2mm to 3mm past the limbus, so diameters of 16mm to 18mm are typical. The lens is left in place for two to four weeks as continuous wear. If the bleb and anterior chamber are formed, but the eye is still Seidel positive, the bandage lens should be reapplied. Topical antibiotics help to prevent infection while the lens is in place.

Therapeutic scleral prosthetic devices are used in long-term treatment plans when a chronic and ongoing injury to the ocular surface exists, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and graft vs. host disease. These diseases in and of themselves pose clinical challenges, as they represent highly inflammatory states and, even after years of successful lens wear, may have episodic flares of ocular surface inflammation, resulting in granuloma formation, deep stromal neovascularization and mucus production. These patients’ eyelids can be highly fibrotic, causing lens-lid sensations (Figure 4). Additional structural concerns such as ectropion/entropion, severe meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), symblepharon formation and limbal stem cell deficiency can complicate the fit (Figure 5).

|  |

| Fig. 6. This patient with neurotrophic cornea and severe lagopthalmos wears his prosthetic scleral device 24/7 and had significant resolution over three years, at right. | |

Although tremendously helpful for many patients, therapeutic lens wear can be fraught with complications. Long-term use of lenses, especially with concomitant use of long-term antibiotics and steroids, can lead to resistance and unusual infectious pathogens.5 To mitigate these risks, clinicians should carefully evaluate whether the lens needs to be worn at night. In cases where continuous wear is indicated, a prophylactic antibiotic should be prescribed. In some cases of long-term management with continuous therapeutic scleral prosthetic lens wear, clinicians should consider educating the patient to remove the lens morning and night for cleaning and disinfection, which would eliminate the need for antibiotics (Figure 6).

Table 2. Diagnostic Codes in Support of Therapeutic Bandage Lenses8 |

| G51.0 - Bell’s Palsy H16.01X - Central Corneal Ulcer H16.05X - Mooren’s Corneal Ulcer H16.07X - Perforated Corneal Ulcer H1612X - Filamentary Keratitis H16.21X - Exposure keratoconjunctivitis H18.83X - Recurrent erosion of the cornea M35.01 - Sicca syndrome (Sjögren) with keratoconjunctivitis S05.0XXX - Injury of the conjunctiva and corneal abrasion without foreign body T15.0XXX - Foreign body in the cornea |

| **Be sure to include which eye and if initial, subsequent encounter or sequela of the event. |

Additionally, lid hygiene is an integral part of successful long-term therapeutic lens wear to prevent infection and inflammatory events (Figure 7). Patients may have a fear of touching and damaging their eyes when they have significant eye problems and avoid lid hygiene rituals. Lid hygiene treatments such as hypochlorus acid, however, can control the lid biome in an easy, safe and effective way during therapeutic lens treatment.

Other frequent complications include dry eye, lens deposits and corneal hypoxia. Often, the doctor must perform a risk-benefit analysis to determine how to handle each patient based on the indications for use and complications. For example, in the case of persistent epithelial defect with progressive scar or possible perforation, the hypoxia risk is often considered a minimal consequence compared with the risk of imminent loss of the eye. As the eye heals, wearing schedules and lens designs should be adjusted.6,7

|

| Fig. 5. Structural concerns such as ectropion/entropion, severe MGD, symblepharon formation and limbal stem cell deficiency may require highly customized prosthetic devices. |

Cover Your Coding Bases

The first step to properly coding for a therapeutic bandage lens is ensuring the codes support its use. Clinicians cannot use refractive codes or refractive conditions, such as keratoconus, as the primary diagnosis code when billing for a bandage device (Table 2). While the device may have a vision benefit, that cannot be the primary reason for fitting. How the lens therapy is billed depends on the specific diagnosis and other treatments or procedures implemented concurrently. For example, a bandage lens cannot be billed if it is part of a standard treatment protocol and placed on the same day as a surgical procedure (Table 3).8

However, subsequent fitting of a bandage contact lens can be billed as a 92071 CPT code after the surgical day (see, Corneal—and Coding—Protection). This code is payable per eye and should be submitted with -RT, -LT or -50 for a bilateral procedure. The device itself is not considered part of the fitting code and should be billed separately using the appropriate contact lens V code.

Corneal Therapy Goes High-techIn an effort to better mimic the natural cornea for medical therapy, researchers have been working on several 3D-printed bio-gel tissues that show promise for treating many corneal conditions, including limbal stem cell deficiency.1,2 Investigators out of Germany recently invented a 3D cornea-mimicking tissue using human stem cells that was then implanted in a porcine organ culture.1 After seven days, the 3D-bioprinted structures attached to the host tissue, showing for the first time the viability of 3D-printed corneal tissue as a possible corneal therapy in the future.1 Using an existing 3D digital human corneal model, other researchers in the United Kingdom successfully fabricated corneal structures that resemble the native human corneal stroma. The 3D-bioprinted structures were made from collagen-based bio-ink containing encapsulated corneal keratocytes and showed high cell viability both at day one post-printing and at day seven.2 These exciting innovations, while years away from clinical application, may one day transform how we care for corneal wound patients.

|

While this code is payable during the global postoperative period, it can only be billed once. Therefore, if a patient is coming back weekly for adjustment or replacement of the bandage contact lens, the contact lens services are not considered a fitting and should be included in the E&M code for that day. Because the supervision rule does not apply to this code, a technician may perform this service. This code is never used for removal of a bandage lens.

The payment on this code is typically very low, with a Medicare national average of $38.52.

|  |

| Fig. 7. This patient with severe meibomian gland dysfunction after trauma discontinued the habitual lid hygiene during therapeutic lens wear, at left, compared with contralateral eye at right. | |

The 92071 CPT code is specific to soft lenses, not a therapeutic scleral prosthetic device. The appropriate code for these lenses is V2627 (scleral cover shell), not V2531 (contact lens, GP, scleral), which is for the correction of vision. Many medical plans no longer cover scleral lenses and services because they are covered under vision plans; however, they will cover a therapeutic scleral prosthetic device for protection of the ocular surface. The Medicare national average for the V2627 code is $1,232.25.

Table 3. Procedures That Include the Placement of a Bandage Contact Lens on the Same Day of Service |

| 65435 - Superficial keratectomy 65780 - Ocular surface reconstruction; amniotic membrane transplantation 65781 - Limbal stem cell allograft (e.g., cadaveric or living donor) 65782 - Limbal conjunctival autograft (includes obtaining graft) 68371 - Harvesting conjunctival allograft, living donor 66999 - Refractive surgery (unlisted procedure code) 65770 - Keratoprosthesis 0402T - Corneal collagen crosslinking |

The rules on the V2627 code are vague and vary by insurer. Some insurers use the V2627 code solely for coverage of the durable medical equipment portion of the service, while others include the evaluation, fitting and follow-up care for up to six months. Office visits are always billed separately for evaluation of the ocular disease.

It is not always clear how often the V2627 code can be billed. For example, it is used for a painted ocular prosthesis, which is traditionally replaced less frequently than a therapeutic scleral prosthetic device. Replacement devices are supported when necessary to prevent a significant disability, when the prior prosthesis was lost or destroyed due to circumstances beyond the recipient’s control, the prior prosthesis can no longer be rehabilitated or a combination. Be sure to call the insurer prior to fitting and designing a therapeutic scleral prosthetic device to discuss the specific coverage and rules.

Therapeutic device fitting can be one of the most rewarding and clinically fulfilling experiences. It is also full of medical and financial risks. Before starting a fit, be sure you understand the time and materials necessary to care for the patient and the financial compensation. Often, standard fitting protocols do not apply to therapeutic lenses; instead, these patients require novel designs and materials. Experience, however, can heal all wounds.

Dr. Sindt is the director of contact lens service and clinical professor at the University of Iowa.

|

1. Erdal NB, Adolfsson KH, De Lima S, Hakkarainen M. In vitro and in vivo effects of ophthalmic solutions on silicone hydrogel bandage lens material senofilcon A. Clin Exp Optom. 2018:101:354-62. 2. Bendavid I, Avisar I, Serov Volach I, e al. Prevention of exposure keratopathy in critically ill patients: a single-center, randomized, pilot trial comparing ocular lubrication with bandage contact lenses and punctal plugs. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):1880-6. 3. Lee YK, Lin YC, Tsai SH, et al. Therapeutic outcomes of combined topical autologous serum eye drops with silicone-hydrogel soft contact lenses in the treatment of corneal persistent epithelial defects: a preliminary study. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39(6):425-30. 4. Edmunds B, Thompson JR, Salmon JF, Wormald RP. The national survey of trabeculectomy III early and late complications. Eye. 2002;16:297-303. 5. Hogg HDJ, Siah WF, Okonkwo A, et al. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia - A case series of rare keratitis affecting patients with bandage contact lens. Eye Contact Lens. January 22, 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. 6. Maulvi FA, Soni TG, Shah DO. A review on therapeutic contact lenses for ocular drug delivery . J Drug Delivery. January 29, 2016. [Epub]. 7. Durrie S, Wolsey D, Thompson V, et al. Ability of a new crosslinked polymer ocular bandage gel to accelerate reepithelialization after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(3):369-75. 8. Ophthalmic Coding Coach, American Academy of Ophthalmology. |